Gladstone's Library

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Of British Prime Ministers, William Gladstone – whose accent was under discussion on the Today programme this morning: can you tell he was from Liverpool? – stands out as one of the most dedicated bibliophiles. As he acquired more and more books, he got into the habit of awarding his children prizes for finding new places to put them. He would ultimately own more than 32,000, of which he read some 22,000 (he kept a record) and annotated 12,000.

Gladstone’s daughter Mary Drew wrote of his desire “to bring together books who had no readers with readers who had no books”. He was a trustee of the London Library, and helped to found a number of reading rooms. He also saw to it that his own books at Hawarden Castle, North Wales, were used by local people when he was away. Reading, he said, offered a “vital spark to inspire with ideas altogether new”.

When the idea of an E. B. Pusey memorial library was mooted in 1882, Gladstone considered what might be done with his own books after his death; he owned more than Pusey had had, he reflected, somewhat put out, and they covered a wider field. So at the age of eighty-two he bought some land and set up a corrugated iron building three-quarters of a mile from the Castle. With the help of his daughter and a member of his staff, he carried his books there in a wheelbarrow, and arranged them on shelves using a catalogue system of his own devising.

He was creating a library “for the pursuit of divine learning”, open to clergy, theologians and members of the public: having overseen the disestablishment of the Church in Ireland, Gladstone worried that the same would happen in England, and that the Anglican Church (of which he was a committed member) would become a sect, cut off from the important discussions of the day. Even so, the library was to serve not only Christian ideologies, but all of them. For most of its life since, the library has been called St Deiniol’s (it is now simply “Gladstone’s Library”), but Gladstone originally named it Monad – oneness, one, the original number. It reflected his belief that, as long as people studied solidly and seriously, the truth would be served.

After Gladstone’s death in 1898, the present library building was commissioned as a memorial. It was designed by John Douglas, and is considered his masterpiece. A residential wing was added in 1906. A small staff continued to acquire books along the lines Gladstone had himself; almost 40 per cent of Gladstone’s books were what could be labelled theology, and as recently as fifteen years ago, about 70 per cent of those who used the library were clergy.

But since 2009, when Patrick Barkham, the author of The Butterfly Isles, visited and wrote an article about it, there has been a lot of interest from what the library’s warden Peter Francis refers to as “the Hay-on-Wye crowd”. And understandably, I thought, as I wandered round for the first time earlier this month. If you like reading books and perhaps writing them too, why wouldn’t you want to visit a beneficent, historically interesting institution with a spectacular library, a beautiful setting, a studious atmosphere, leather armchairs and a café?

Post-Barkham, Francis saw more clearly what the library’s future would be. He and his staff looked closely at the collections – History and Politics; Religion; Culture, both classical and contemporary; Modern languages; Law. The Law section was over-large and out of date. They refocused the various sections, devised new courses and events, and “boutique-ized” the twenty-six bedrooms. Francis wrote to Damian Barr, who wrote back enthusiastically, suggesting a writers-in-residence programme.

The programme is now in its fourth year. Gladfest was inaugurated last year, which led to Hearth – “an opportunity to meet, talk and create with the Library’s writers in residence and other participants over a weekend of writing related activity”. At the Hearth events I attended, Melissa Harrison, Neil Griffiths, Tania Hershman and Adnan Mahmutović talked about their careers, collectively and individually. Mahmutović, who fled the war in Bosnia in 1993 and now lives in Sweden, led a relaxed discussion about “writing across borders”. Harrison, behind a lectern in the bright and airy chapel, described how she summoned the confidence to start writing fiction in her mid-thirties, and developed a method based firmly on experimentation. She has trouble, she told us, with the question “Where do you get your ideas?”: “It assumes that the writer had an idea at all”. As a member of the library’s staff pointed out, there is no green room, which is part of the appeal. The writers and audience mingle, glasses of wine in hands.

What would Gladstone be doing today?, Francis and his colleagues like to ask themselves. Francis believes that Gladstone would be concerned about the lack of understanding between Islam and the Western world, so an Islamic study room has been set up in the library. Lectures by people such as David Cannadine, Peter Tatchell and A. C. Grayling invite people to consider what Gladstonian liberalism might mean today.

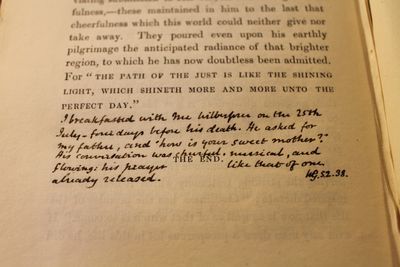

But the main attraction remains the books. Gladstone’s own volumes have recently been gathered together in one place, and new annotations are being found all the time . . . .

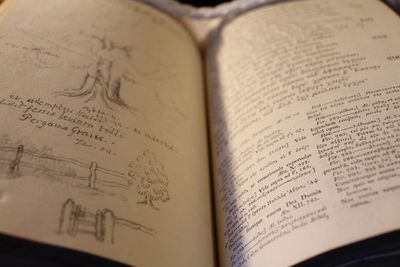

Above: Pages from Gladstone's school books

Below: A page from Gladstone's copy of The Life of William Wilberforce by Robert Isaac Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce (1838). On the final page, Gladstone has written: "I breakfasted with Mr Wilberforce on the 25th July – final days before his death. He asked for my father, and 'how is your sweet mother?' His conversation was cheerful, musical and flowing: his prayer like that of one already released".

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers