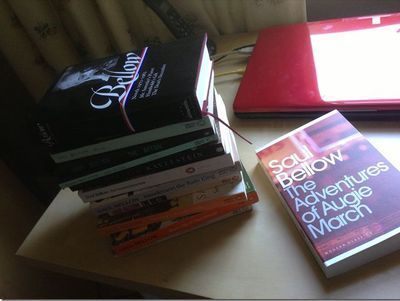

Reading Saul Bellow

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I have a confession

to make: I have yet to read The

Adventures of Augie March. Published in 1953, Saul Bellow’s first “big”

book was described by Martin Amis, Bellow’s most eloquent and fervent

reader-critic, as “the great American novel”. No real excuse not to have read

it then.

But I have read all of Bellow’s other novels. Reading Bellow has been like a long, broken

but hugely rewarding journey. I first became acquainted with his work twenty-five years

ago, partly prompted by Anthony Burgess’s influential book Ninety-Nine Novels: The best in English since 1939. (Burgess’s

hope was that someone would choose one of his works as the 100th –

A Clockwork Orange perhaps?) Burgess

opted for Bellow’s The Victim as one

of his two best novels for the year 1947, the other one being Malcolm Lowry’s

Under the Volcano (not read). He called Bellow’s second novel a “quiet

masterpiece”. At the time, that seemed an accurate assessment. I’m sure it still

applies.

For some

unfathomable reason – what dictates our reading patterns?, I wonder – I didn’t

read another Bellow for a further three years or so: Something To Remember Me By, which included the novellas The Bellarosa Connection and A Theft, as well as the wonderful title

story of rites of passage in 1930s Chicago. But several more years passed

before I had a serious attack of the Bellows: the novella Seize the Day, More Die of

Heartbreak (great title, great book), Dangling

Man (his first), Herzog, The Actual, and Henderson the Rain King. I wasn’t at all persuaded by this last book,

but ploughed my way diligently through it. I’m still baffled by the high status

it’s accorded.

Amis’s first

published collection of essays The

Moronic Inferno and Other Visits to America (1986) took its title from Humboldt’s Gift (1975): “Now the moronic

inferno had caught up with me”, says the narrator Charlie Citrine as he surveys

the ruins of his swanky Mercedes which has been smashed up with baseball bats

outside his Chicago apartment.

Meanwhile, in his

memoir Experience, Amis writes, of

Bellow’s last novel Ravelstein

(2000), “I have to keep reminding myself that the author was born, not in 1950

but in 1915” (he died in 2005). There is indeed a remarkable energy to the

book, published in Bellow’s eighty-fifth year. The phenomenon of writers

remaining near the top of their game well into their eighties is still pretty

rare (and perhaps restricted to the twentieth and now the twenty-first century). If one

excludes poets, only a few names come to mind: the leading figure of the nouveau roman Nathalie Sarraute was

still near her best in her nineties. Her fellow nouveau romancier Claude Simon published one of his finest (and

briefest) works Le Tramway at the age

of eighty-eight – a sunny, captivating and fictionalized account of the novelist’s

childhood in a seaside town in the south-west of France.

On the debit side,

Philip Roth, who recently turned eighty, has declared that he will not be writing

any more fiction. The late Gore Vidal disappointed many of his readers with a

slackly written and woefully under-edited follow-up, Point to Point Navigation, to his fascinating, waspish memoir Palimpsest (1995). It might have been

better if the second book had not seen the light of day, particularly as it

turned out to be Vidal’s last work.

But Ravelstein doesn’t flag; as a homage to

and undisguised portrait of Bellow’s late friend the academic Allan Bloom,

whose best-selling book The Closing of

the American Mind was such a divisive work when it appeared in 1987, it

brings out the flamboyance and slight preposterousness of this larger-than-life

figure. Bellow clearly held Bloom in the highest regard, and at one point has his narrator compare him favourably with Diderot: “’The Palais Royal’ – Ravelstein

gestured loosely toward it – ‘was where Diderot walked late every afternoon and

where he had his famous conversations with Rameau’s nephew. But Ravelstein was

by no means like the nephew – that music teacher and sponger. He was above

Diderot, too. A much larger and graver person . . .”. Really?!

“The main thing

about Chicago is that it’s not New York”, wrote Bellow, of the two cities at

the heart of his work (Montreal might be a third). A blog is no place for lit

crit (and I’m no expert on American fiction) but it seems to me that if you

want to learn about life in twentieth-century urban America, and the Jewish

experience in particular, as well as much else too, Bellow’s work should be the

first port of call. And it might be said that his peculiarly European sensibility both expands and deepens its qualities.

And of course

there’s the humour: one of my favourite characters is the shameless Pierre Thaxter

in Humboldt’s Gift, a literary con man, serial

adulterer and father of nine, who travels across the

Atlantic on a liner in first class – his mother picks up the tab – in spite of

the fact that he’s flat broke (significantly, Thaxter is Californian). Citrine

tells him:

“If I had no

cash, I’d ask my mother to put me in steerage. How much do you tip when you

get off the France in Le Havre?” I

asked him.

“‘I give the chief

steward five bucks.”

“You’re lucky to

leave the boat alive.”

“Perfectly

adequate,” said Thaxter. “They bully the American rich and despise them

for their cowardice and ignorance.”

I have a Library of

America edition of Novels 1970–1982,

a period that represents the high point of Bellow’s career, the possessively

titled trio Mr. Sammler’s Planet, Humboldt’s Gift and The Dean’s December. One thing that struck me about this otherwise

very handsome volume is the extraordinary number of typos it contains,

particularly as the reader is assured that the “texts are presented without

change, except for the correction of typographical errors”. Here’s just a

sample selection: “Punisment”, “Sannnler” for Sammler, numerous “he”s for “be”s

and “be”s for “he”s, “staff” for stuff and so on, as well as the comical “New World Symophony” – none of them, granted,

an impediment to comprehension, but still . . . . I imagine these errors will

now remain uncorrected.

(Writing as someone

whose shared responsibilities at the TLS

include making sure the paper goes to bed with its hands as clean as possible,

i.e. proofreading the pages – the weekly equivalent of proofing a 50,000 word

novel – I always react to typos spotted too late as if I’ve taken a blow to the

solar plexus. I’m determined never to let through weirdly common misspellings

such as “elegaic” and “pharoah”.)

In her newly

published Literary Miniatures

(translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan; Seagull Books, $20/£13), a collection of

interviews with (non-French) authors, Florence Noiville, editor of foreign

fiction for the weekly supplement Le

Monde des Livres, describes meeting Bellow near his Vermont fastness in

1995. He greets her with the question “Suis-je celui que vous attendiez?” – “Am

I the one you were expecting?” It is strange to hear French spoken in this

remote inn in Vermont"; but it’s a reminder of Bellow’s early Montreal

upbringing, his Paris sojourn in the late 40s, and enduring Francophilia. Later in

the piece he reveals that “J. D. Salinger lives on the other side of these

hills, in New Hampshire. He’s a bear. Doesn’t see anyone. Never goes out. Worse

than I am”.

Now, on to Augie March.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers