Whish! James Joyce's river speaks

by THEA LENARDUZZI

“The order is othered.” This is one of the few lines I can quote with any certainty from riverrun, Olwen Fouéré's one-woman adaptation of Finnegans Wake, performed in England for the first time this week at the Shed. But, then, it might have been “The other is ordered”, for no sooner had Fouéré said the words than they were carried off on an unpredictable tide of language which ran, without interruption, for just over an hour. Another line bobs to the surface, now: “I'll be your aural highness”; or was it “your oral heinous”?

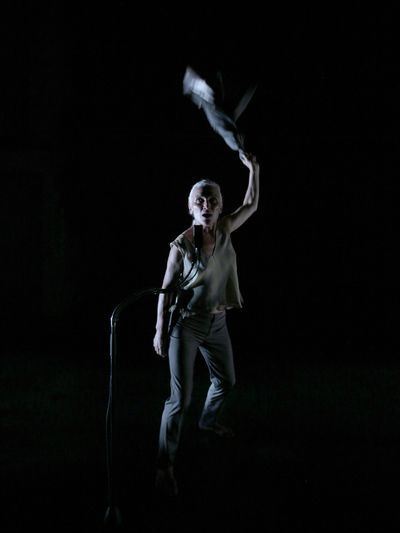

Fouéré is a striking figure, in a grey silk camisole, her silver hair tied back loosely, as she snakes her hips gently, shifting her weight from side to side. She took as her starting point, when devising her monologue, the famously interrupted last line in Book Four (the beginning of the end of Joyce's masterpiece): “A way a lone a last a loved a long the” – which comes full circle to the book's very first line, “riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs”. Book Four sees Anna Livia Plurabelle – the embodiment of the river Liffey, or Life, which runs through Dublin and, indeed, through everywhere and everything – be swept out into the sea of time. Fouéré speaks for the river. Her first three words are Sanskrit, “Sandhyas! Sandhyas! Sandhyas!”, meaning the break of dawn, and there are echoes, too, as Fouéré stands before us, of Molly Bloom's “and yes I said yes I will Yes”.

But to make this comparison is, perhaps, to ignore Joyce's comment to friend while writing the book he preferred to call his Work in Progress (a process which took him roughly seventeen years, or “at least 1,200 hours”, Ian Pindar says in his biography of Joyce): “Je suis au bout de l'anglais” – and this from the man who had once declared English “the most wonderful language in the world”. The upshot, Finnegans Wake, is a triumph of multilingualism, or, in a sense, supralingualism – a “language which is above all languages”, “pure music” (in Joyce's words). This is, perhaps, never more alive than in Fouéré's soundscape which, as the novel itself puts it, makes “soundsense and sensesound kin again” – doubly heartening considering that most people will never read Joyce's original, “the greatest experimental novel of all time” (Pindar again) or “the best example of modernism disappearing up its own fundament” (as J. G. Ballard saw it).

As a result of the process of cannibalization to which Fouéré has subjected Joyce's text – “moving backwards towards the source ... intuitively selecting journey points, skipping chunks of text, inserting a couple of short passages from earlier in the book” – motifs recur and themes emerge. The story of Joyce's life, for instance, is brought closer to the surface. “As is, without a doubt”, Fouéré explains, “the voice of Lucia, Joyce's incarcerated daughter, with her silenced rage, her dancer's brilliance and the multilingual fire of her wit.” Daughter and father wash together in the riverrun, and joy and mourning become indistinguishable in Liffey's exclamation as it nears the sea: “I rush, my only, into your arms. I see them rising! Save me from those terrible prongs! Two more. Onetwo moremens more. So. Avelaval . . . Whish! A gull!” She is born – “a gull!”, a girl – into an ocean of opportunity, and at the same time she is undone, pulled under and lost in the depths.

Fouéré perfectly captures the babbling nature of Joyce's prose, the chopping and changing between register, theme, tone – conversational, almost cute, one minute, garbling the Ten Commandments and spitting damnations the next. She has described the Wake as “a seam of dark matter somewhere between energy and form”, an interpretation close to Samuel Beckett's that “Here form is content, content is form . . . . [Joyce's] writing is not about something; it is that something itself”. And, as all hope of narrative structure or fixed characters goes asunder to sound, it is this something that asserts itself; for, by bringing the rules of logic crashing together, swishing them around, drowning them, splicing them and turning them on their heads, a new order emerges, fluid and unfixed, which performer and audience understand implicitly. We all laughed at the same moments (for, lest we forget, Joyce proclaimed himself “a great joker at the universe”) and leaned further forward in our seats, as though to catch some secret wisdom, at others.

The performance culminated in a well-deserved standing ovation for Fouéré; and, of course, for Joyce's book itself, still something of a work in progress, after all, still fulfilling the author's intention “to keep the critics busy for three hundred years”.

Olwen Fouéré's riverrun is at the Shed until March 22.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers