After Arden: Ann Thompson and Hamlet

By MICHAEL CAINES

A characteristically deft, Janus-faced observation on page 52 of John Carey's new book, The Unexpected Professor, has him going, as a boy, to see Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in Antony and Cleopatra, at the St James's Theatre in 1951. "Not that Olivier and Leigh were particularly bad", he recalls, "It was just that, as often with Shakespeare, when actors start to waddle around and gesticulate[,] it seems absurdly inferior to what your imagination has created from words on the page." The young critic comes fresh from reading all of three Shakespeare plays as set texts at school, and intoning Othello's suicide speech ("Soft you, a word or two before you go . . .") in front of the mirror at home, "wearing my red dressing gown, the nearest thing I had to Moorish garb", before stabbing himself with an imaginary dagger.

John Carey's recollections of coming away underwhelmed from seeing two great actors at work comes to mind after hearing the grandly named Annual London Shakespeare Lecture in Honour of Stanley Wells. This was given last night by Ann Thompson at the University of Notre Dame's London branch. Her subject was that most ubiquitous of Shakespeare's speeches – not necessarily a soliloquy, mind you – in which the Prince of Denmark weighs up whether or not he should –

Well, there doesn't exactly seem to be unanimous agreement about what "To be or not to be" is about. Suicide? Killing Claudius? Life in general? People keep changing their minds. Nor can they agree where the speech should go in the play Hamlet (theatre directors congratulate themselves on moving it so that it doesn't immediately follow, and contradict, "O what a rogue and peasant slave am I", but tend to pick a spot already taken by the so-called "bad" quarto, the first, of 1603), nor who hears it and from where (do Claudius and Polonius leave the stage altogether, or linger nearby?).

And then, as Professor Thompson (recently retired from King's College London, co-editor of Hamlet in the Arden edition, third series) pointed out, there are the verbal uncertainties and matters of interpretation in performance: is the poor man or the proud man's "contumely" that Hamlet counts among the "whips and scorns of time"? Is Polonius being considerate towards or dismissive of Ophelia when he turns to her and says "How now, Ophelia? / You need not tell us what Lord Hamlet said; / We heard it all"?

So Ann Thompson's rhetorical question was: when it comes to Hamlet, "have we heard it all?".

Her answer – or at least one of the many prudent observations in this lecture, which was well attended by her fellow editors, including Stanley Wells, the odd actor and, even odder, some members of the public – was that this supposedly all-too-well-known speech and the scene to which it belongs, 3.1, are full of perplexities to keep us guessing, to show us that we can't, and probably never will, have heard it all.

There's pleasure in these perplexities, too. After ten years' immersion in the task of editing it, and after seeing more productions of the play than she can count, Professor Thompson herself seems to have a preference for versions of Hamlet which can surprise her, rather than any convictions about the inherent superiority of her own view of the play to the absurdities foisted forth by waddling actors.

Peter Brook's staging in 2000 and 2001, she recalled, starring Adrian Lester, seemed to promise something very exciting: Hamlet without "To be or not to be". It wasn't in Act Two or Three. Would Lester leave it out altogether? But no, there it was, replacing its supposedly lesser counterpart, "How all occasions do inform against me", in Act Four.

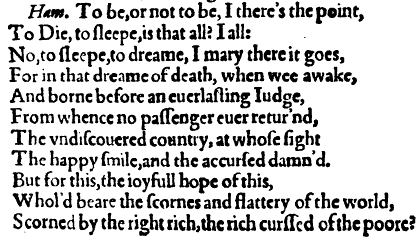

I would have liked to ask her about women playing Hamlet (or directing it, which seems to be even more of a rarity) or maybe the temptation the actor Michael Pennington felt, comparable to her own desire for novelty, perhaps, to adopt the first quarto's version of that speech, "To be, or not to be, I there's the point . . ." (as above).

But open the door to this multiplicity of princes and their dilemmas, and you can see why the RSC once playfully suggested in their in-house magazine that there ought to be a moratorium on the play. And I can see why a friend of mine recently announced, only half joking, I suspect, that if we get round to holding our own Shakespeare evening, a (probably deeply embarrassing) private attempt at a 450th-anniversary celebration, he would be playing Hamlet – hands off! I was duly condemned to Mark Antony. Though whether he meant the Antony of Julius Caesar or Olivier-and-Leigh fame, or both, he didn't say . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers