Peter Stothard's Blog, page 39

September 19, 2014

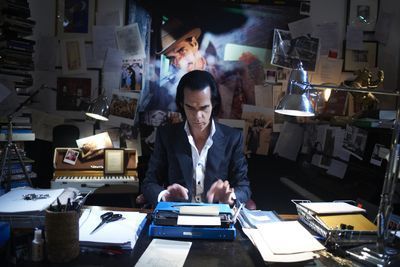

Nick Cave the cannibal

By THEA LENARDUZZI

20,000 Days on Earth, a work of docu-fiction in which Nick Cave plays Nick Cave, is a personal paean to song-writing and the transformative power of performance. Co-written and directed by the visual artists Jane Pollard and Iain Forsyth, the film follows the artist for roughly twenty-four hours on what is ostensibly his 20,000th day of life. Pollard and Forsyth are interested in performance and memory (this much is clear from their previous projects, including a re-staging of David Bowie’s final outing as Ziggy Stardust), and they are interested in Nick Cave (they directed a number of his music videos in 2008). This is good, because Nick Cave is also interested in Nick Cave – and so it would seem is the large crowd gathered with me at the Soho Hotel for this early screening of the film.

“At the end of the twentieth century, I ceased to be a human being”, Cave says in a voiceover as he lies in bed at 11:35am. “Mostly I feel like a cannibal”, he continues – which is, of course, still a human being. His analogy centres on his daily practice of lyric-writing in which he “gathers up experiences” and “cooks” them until they boil over into song. (“Mostly I cook my wife in my pot.”) “It’s a world I’m creating”, he explains, “full of monsters, heroes . . . . violence . . . . They’re all just crooked versions of myself.”

The same could, perhaps, be said of the characters in his novels, And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989) – an over-the-top Southern gothic, borrowing heavily from William Faulkner and the Bible – and The Death of Bunny Munro (reviewed in the TLS, November 6, 2009), a more blithe, often farcical tale about the life and death of a travelling salesman who can barely keep his trousers on. And while it would be unfair to suggest parallels between the author and his earlier protagonist, a mute born of incest into a life of depravity, 20,000 Days on Earth makes clear reference to themes and motifs in The Death of Bunny Munro.

For one thing, both are set in Brighton, where Cave settled in the 1980s (“It's been forcing itself violently into my songs ever since”). Both have their anti-hero drive around the city picking people up – Bunny for sex, Cave for the purposes of brief chats about ageing and their shared musical pasts (Blixa Bargeld sets the record straight on why he left Cave’s band the Bad Seeds in 2003 after twenty years together, while Kylie Minogue describes her first meeting with Cave, before the recording of their duet “Where the Wild Roses Grow” in 1996 – “You were like a mist that rolled in”, she says from the back seat of Cave’s black Jaguar).

This self-referencing – like a cannibal’s burps – is for the most part playful. Recalling the first time he saw his wife, Cave says, “It was like the endless dripfeed of erotic data came together” – cue a breakneck sequence of images of Marilyn Monroe, Jackie O. in mourning, Gustave Courbet’s “L’Origine du monde” and cheap 1970s porn. Sifting through his archive (fictionally transplanted from Melbourne to Brighton), Cave reads “My Last Will and Testament”, from 1987: “I wanted all my money to go to the Nick Cave Memorial Museum.”

The whole is woven through with a thread in which Cave enters a kind of therapy room so Alain de Botton can ask him questions, such as “What is your earliest memory of the female body?” and “What do you fear the most?” Cave’s response to the latter changes throughout the film (for “who knows their own story . . . . It’s all just clamour and confusion”). At first it is losing his memory, because “memory is what we are”. Later, in the studio, he sings, “There’s nothing to fear but a bad idea”; later still, “What I fear most is nature....It’s coming to get its revenge”.

The sessions prompt confessional musings and talk about “slaying the dragon”, which ripple through the rest of the film: “We all want to be somebody else”; “All of our days are numbered”; “We can't afford to be idle”. A clichéd portrait of the artist builds: “I was the kid singing into a broom with the door locked”, wearing “blue jeans”; “I wasn't really into sport”.

Cave plays a dangerous game of Chicken with cliché, similar to that he has played in his novels and which he has not always won. It finds a kind of echo in his memory (real, or otherwise) of messing about on the railway tracks, running onto the bridge as he hears the train coming and jumping off into the river in the nick of time. An example comes when Cave is recording the track “Higgs Boson Blues”: one groans at the hackneyed tale of how he “came upon a crossroad / The night was hot and black / I see Robert Johnson with a 10-dollar guitar / Strapped to his back looking for a tomb”.

But Cave hangs on a little longer, egging himself on:

“Well here comes Lucifer with his canon law / And a hundred black babies running from his genocidal jaw”

And then performs a shimmy, which just about saves him:

“He got the real killer groove / Robert Johnson and the devil, man / Don't know who is gonna rip off who.”

Perhaps what Cave should fear most is losing this sense of playfulness. “Counterpoint is the key”, he says of song-writing, and an essential counterpoint within this self-absorbed project is humour and self-irony. It surfaces throughout, but not quite as often as I would have hoped. We glimpse it early in the film when, while the band dictate their coffee orders to an assistant, Cave warms up on the piano: “There's something you remind me of when you sing that”, Warren Ellis, a long-time collaborator of Cave's, interrupts. “Tim Buckley?”, Cave suggests. “No. It's Lionel Richie.” Lyrics about a “one shot latte” build into the ballad of the “Lionel latte”. “You've totally blown the mojo out of that one”, Cave sighs. Which may well be the case for that particular song, but it's these instances of levity that save 20,000 Days on Earth from disappearing under the freight train.

September 18, 2014

Epidermal doodles

By DAVID COLLARD

“The Skin Project”, launched in 2003 by the American artist Shelley Jackson, is a 2,095-word short story “published exclusively in tattoo form, one word at a time, on the skin of volunteers”. The first word – which is “skin” – adorns Jackson’s wrist in Baskerville font, and she stipulates that each volunteer, once issued with their word, should likewise employ a “classic book font such as Caslon, Garamond, Bodoni, and Times Roman”, adding that the tattoo “should look like something intended to be read, not admired for its decorative qualities”.

Prompted by my belated discovery of this I’ve been looking (and often flinching) at online images of other “literary” tattoos, of which there are thousands. The same “decorative qualities” proscribed by Jackson are very much on display as, wrenched from their printed context, lines of prose and poetry are elaborated with baroque fonts, fancy scrolls and curlicues and much use of faux-Gothic script, more Motörhead than Montherlant.

Literary tattoos fall into two broad categories: photorealist portraits of authors and quotations from their work. Most common is a quotation, drawn for the most part from a small cohort of hip writers. Kurt Vonnegut is very popular, with numberless Slaughterhouse-Five fans sporting the author’s laconic coda “So it goes”. So too is Charles Bukowski, William Burroughs, Hunter S. Thompson, Kurt Vonnegut, Jack Kerouac and J. R. R. Tolkien. People also seem to favour lines from childhood classics (The Little Prince, Harry Potter) and high school staples (Maya Angelou, J. D. Salinger, Harper Lee and Edgar Allan Poe), but there are some surprises, such as the nine lines from Little Gidding covering the back of an English teacher from Hawaii, who writes: “I chose to tattoo the first four and last five lines together (I didn’t have the guts at the time to go whole hog and tattoo the entire section. I wish I had.)”

There is a perhaps inevitable trend for literary tattoos among celebrities. Johnny Depp, the epitome of Hollywood cool, has Joyce’s “Silence Exile Cunning” (sic) in big faux Gothic script on his forearm. Lady Gaga is adorned with lines from Rilke; Angelina Jolie from Tennessee Williams.

Lady Gaga performs in concert at DAR Constitution Hall on September 29, 2009 in Washington, DC. Photo by Paul Morigi/WireImage/Getty Images

Leafing through Eva Talmadge and Justin Taylor's The Word Made Flesh: Literary tattoos from bookworms worldwide (2010) and looking at the associated online archive I couldn’t find a single literary tattoo I liked. I’m deeply sceptical about the self-commodification involved when asserting non-conformism and individuality by shelling out on an epidermal doodle, but I wanted to get an opposing view so I asked a good friend about it. He’s a writer in his fifties and has “Voyaging through strange seas of thought alone” emblazoned on his chest because (he says) it’s his favourite line in English poetry and because he “thought it was funny to have Wordsworth tattooed on oneself”. When I asked him why he didn’t quote the full line from The Prelude (“A mind voyaging . . . etc”), he replied, reasonably enough, that it wouldn’t fit. Then I asked him about tattoos in general, and literary ones in particular, and he said: “People I know see it as a continuous point of reference and don’t give two hoots about being thoughtful or cultured. It’s often because they want a tattoo but want to show they have a certain degree of awareness of the process”.

A casual census suggests that the practice of literary tattooing is largely confined to youngish American fans of cultish American authors, though it’s becoming more popular in Britain. It’s made me wonder which author’s portrait and which quotations I would, if so minded, have inscribed on myself. Do I really like anything I’ve read that much? Then I thought of the fine opening lines of the poem “Liverpool” by Michael Donaghy, who died the year after “The Skin Project” (a quarter of the way through, according to the last report) began and didn’t live long enough to see the rise of the literary tattoo:

“Ever been tattooed? It takes a whim of iron,

takes sweating in the antiseptic-stinking parlour,

nothing to read but motorcycle magazines

before the blood-sopped cotton, and, of course, the needle,

all for — at best — some Chinese dragon.

But mostly they do hearts”

“It takes a whim of iron” might be my own choice for a discreet inking – in Times New Roman, of course, or even Gill Sans, and in legible 12-point.

September 17, 2014

That joke isn't funny anymore

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Last night, in the opulent surroundings of the Commonwealth Foundation’s headquarters, just off Pall Mall, a panel of Commonwealth writers came together, chaired by the Sri Lankan novelist Romesh Gunesekera, to discuss the place, if indeed there is one, of humour in conflict. The event coincided with the launch of the Foundation’s 10-by-10 Podcasts, a series of ten-minute contributions from writers across the Commonwealth, including Margaret Atwood (Canada), Binyavanga Wainana (Kenya) and Gunesekera himself.

Back in Malborough House, however, Gunesekera was joined by Leila Aboulela, a Sudanese playwright and novelist, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, a Ugandan novelist and poet (and the winner of last year’s Commonwealth Short Story Prize), and Kei Miller, a Jamaican writer for whom, apparently, “a novelist” is “the worst thing in the world you could be called” – a contentious point to make in a room full of (amateur) novelists. (Miller writes in multiple forms at the same time – “It’s a form of ADD”, he says – poem, essay and novel are in constant rotation on his computer screen.) His point is rooted in the idea that looking at the world through the lens of any one genre (be it romantic, scientific or otherwise) risks minimizing the complexity of the situation. We also need to dispel the myth that humour cannot carry heft – “there is great terror and profundity to be found in humorous writing”.

For Miller, reality is an endless and contentious discussion which, in his most recent collection of poems The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion, takes place between a Rastafarian and a cartographer. He shows how the early maps of Jamaica are pock-marked with blind spots and “colonial purposes”, creating a landscape in which humour and contention alternate and co-exist. In Poem 10, “in which the cartographer asks for directions”, we hear a virtuoso performance of Jamaican patios which leaves us as bewildered (though laughing) as the poem’s supplicant, while Poem 11, “on the thoughtless ungridded shape of our city”, takes a more accusatory approach. Miller uses mapping as a metonym to shame the cartographer – who here stands for all the supposedly objective “men of science” who colluded in the betrayal of Jamaica. The cartographer's bowing to the colonizers’ desires to avoid the black neighbourhoods on their travels through the city resulted in the long, contorted streets which continue to add hours to the daily grind of modern Jamaicans.

Leila Aboulela is guided more by character, and humour for her is impossible unless there is distance. “If I’m very close to my characters,” she said, “humour is not possible.” By way of example, she talked about The Translator (1999), her semi-autobiographical novel about a young Sudanese woman who moves to Aberdeen (where Aboulela now lives) and finds herself utterly baffled. “I had not meant it to be funny” – and she was surprised when, at a reading attended by Doris Lessing, the British novelist laughed aloud at the character’s struggles. Context and culture is, of course, everything, and some jokes remain untranslatable or invisible to others. (As a general formula, Miller offered “A B C X” – “‘A B C D’ isn’t funny – you need to break the sequence . . . to create tension.”)

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi related a similar experience of reading to an audience in Kampala. They found her story of a widow who discovers that her husband had another wife hilarious; her listeners in Britain had apparently not. “In Uganda, you need humour; stories need humour – it’s the best way to talk about pain”, she explained. (Later, Makumbi cited A Modest Proposal as an early influence on her writing; “There is normally a grim humour in my writing” – which, to me at least, would suggest it is a perfect fit for British readers.)

As ever with these things, however, there were no answers, nor even a consensus, but rather a proliferation of questions: can humour in writing bring social and political change, or does humorous writing in fact dispel tension, thus preventing further action? (This, of course, begs the bigger question, “What is the point of writing?”, which Miller, in turn, reformulated as “How can I get you to hear what I am saying?”); how can we control humour – indeed, can it be controlled at all? – in an increasingly globalized (literary) world? Both Makumbi and Aboulela confessed that they could never send up a culture other than their own – “And never the Queen!”, our host tonight, after all; Miller, meanwhile, acknowledged no such limits.

September 15, 2014

The unanswerable Charles Ives

By MICHAEL CAINES

Misunderstood in its own time and occasionally the cause of controversy in more recent years, the music of Charles Ives has also had its determined champions; in last week's TLS, Carol J. Oja reviewed an account of this mixed history, Charles Ives in the Mirror, and notes that one of those champions was Leonard Bernstein. Art gains new meaning in new contexts, it's sometimes said, but the piece of music I have in mind in connection with Bernstein only emerged into public view long after Ives had revised it (before the Second World War), let alone composed the first version (before the First World War). What changed?

Well, basically, everything. . . .

Ives died in 1955. Four years later, Bernstein was touring the Soviet Union with the New York Philharmonic and The Unanswered Question. Formerly designated "A Contemplation of a Serious Matter, or The Unanswered Question", this piece could now be reinterpreted as a contemplation of what Oja calls "unresolvable Cold War tensions", with Ives's "Perennial Question of Existence" (an uneasy, octave-leaping trumpet motif) and "Fighting Answers" (the increasingly frenetic woodwind), over the piece's sustained "Silence of the Druids" (a not-so-silent battery of slowly shifting strings).

Talk about being ahead of your time – or rather, being in desperate need of other people catching up. Bernstein, on that same tour, set out to be a radical in his own way. He made the politically provocative gesture of visiting Boris Pasternak (who had won the Nobel Prize for Literature the previous year, following the banning of Doctor Zhivago in the USSR and its subsequent publication abroad) and took the coda of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony drastically uptempo ("I liked it", Shostakovich said, reassuring another conductor that it would be fine for him to do likewise). That sounds like nothing to get het up about, perhaps, but concert hall regulars have always loved their proprieties. For good measure, Bernstein had also put one Muscovite critic's nose out of joint by taking the unprecedent step of addressing the audience before the performance, in order to introduce them to both Ives and The Unanswered Question, and then, given the enthusiastic response, he repeated the piece straight away.

I've linked in the second paragraph above to a recording of Bernstein conducting the piece that, relatively speaking, doesn't seem to have been played very much on YouTube; embedded at the top of this post, however, is a recording of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas. It's a good minute slower than Bernstein's account, which I prefer, and the video has a few (helpful introductory) notes, too.

Carol Oja's piece reminds me of some other Ives champions: the Kronos Quartet, whose "They are there!" adds a layer of strings to a recording of the composer himself, making its jauntiness even more disconcerting in the process; and also Leonard Stokowski, who dared to give the Fourth Symphony its full premiere, with the American Symphony Orchestra, in 1965. Stokowski ended up performing this technically challenging work – which I'd love to see performed live some time – with two additional conductors. Here's a glimpse of two of them, hard at work trying to control the second movement (Comedy: Allegretto):

"Up to the last minute", José Serebrier was to recall of this piece, which he later conducted alone, "many of the players could not really understand what it was all about." I think that comment could stand for the many who heard Ives in his own time and found the questions his music posed then, and still poses, unanswerable.

September 12, 2014

‘Apolitical ponce’: W. H. Auden in the OED

By DAVID COLLARD

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter has appeared more or less annually since its inaugural issue in April 1988. Plain in layout, wonderfully rich in content, scholarly but not academic, it's an indispensable omnium gatherum of all things Auden – eccentric, eclectic, unpredictable and endlessly fascinating.

My favourite Newsletter item dates back to the fourth issue (October 1989) when a young Toby Litt, long before he achieved fame as a novelist, contributed a dazzling little essay entitled “From ‘Acedia’ to ‘Zeitgeist’: Auden in the 2nd Edition of the OED”. (Before I go any further I have to gratefully acknowledge my debt to his essay as a source for this blog.)

Litt begins his piece with a quotation from Auden, taken from an interview in 1971:

“One of my great ambitions is to get into the OED as the first person to have used in print a new word. I have two candidates at the moment, which I used in my review of J. R. Ackerley’s autobiography. They are ‘Plain-sewing’ and ‘Princeton-First-Year’. They refer to two types of homosexual behaviour.”

Auden’s ambition was realized posthumously with the appearance in 1989 of the twenty-volume 2nd edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, now available online as "OED3", from which the following definitions are taken.

This admirably explicit definition of “Princeton-First-Year” cites Auden’s piece on the Ackerley autobiography (My Father and Myself) in the New York Review of Books:

“Designating a form of male homosexual activity in which the penis is rubbed against the thighs or stomach of a partner.

1969 W. H. AUDEN in N.Y. Rev. Bks. 27 Mar. 3/4 My guess is that at the back of his mind, lay a daydream of an innocent Eden where children play ‘Doctor’, so that the acts he really preferred were the most ‘brotherly’, Plain-Sewing and Princeton-First-Year.”

A later citation comes from the TLS, with a discreetly explicit Latin tag:

“1980 Times Lit. Suppl. 21 Mar. 324/5 ‘Princeton-First-Year’ is a more condescending version of the term ‘Princeton Rub’; that is, coitus contra ventrem.”

When it comes to “plain sewing” as a euphemism for both buggery and masturbation, the OED has it both ways:

“plain sewing n. (a) Needlework which is functional or practical rather than decorative; (b) slang [popularized by W. H. Auden (compare quot.1980)] , a sexual activity of homosexuals involving mutual masturbation.”

Of course, Auden enriched the language of the tribe far beyond this subversive promotion of mid-century gay slang. He appears 766 times in the second, four-volume OED Supplement published from 1972 to 1986, including quotations from works co-written with Christopher Isherwood, Louis MacNeice and Chester Kallman. Most of these citations are not for being the first person to have used a new word in print, but are included to show a change or extension of meaning. (While this is an impressive total, Shakespeare – by far the most frequently quoted single author – is the source of 33,300 quotations, of which 1,600 come from Hamlet alone.)

That Auden came to feature so prominently in the OED is partly down to the time he spent as Professor of Poetry at Oxford between 1956 and 1961. He became an acquaintance of R. W. Burchfield, a lecturer at Christ Church (Auden’s college) and, from 1957, the editor of the second supplement to the OED. Burchfield, though he had a low opinion of the poet's linguistic scholarship, decided that Auden should be among the major writers whose work merited special attention from the compilers.

Of Auden's 700-plus citations, 110 are original coinages, of which around half are hyphenated compounds such as “angel-vampire”, “swan-delighting” and suchlike poetic figures that have never entered the mainstream; a further twenty-two appear under sub-headings as additional definitions of words already in existence. In all, there are twenty-eight citations (including the entry for “Princeton-First-Year”) for which Auden is credited as the first writer to use the word in print. It's a lexicon that in part reflects the poet's camp and ramshackle character. Toby Litt writes:

“Among Auden's more notable citations are: the first pejorative use of ‘queer’, the first printed use of ‘ponce’ to designate an effeminate homosexual, of ‘toilet-humour’, of ‘agent’ in the sense of a secret agent or spy, of ‘dedicated’ to mean a person ‘single-minded in loyalty to his beliefs or in his artistic or personal integrity’, of ‘shagged’ meaning ‘weary, exhausted’, and of ‘stud’ for a person ‘displaying masculine sexual characteristics’. Further curiosities are the first printed appearance in English of the surrealist term ‘objet trouve’ and the first printed use of ‘What’s yours?’ as an invitation given by the person buying the next round of drinks.”

Not included in the Litt list but noted by Mendelson in his introduction to the reprint of Auden's The Prolific and the Devourer (1939) is the poet's use of the term 'apolitical', its first appearance in print. Other Auden-sourced coinages include "Mosleyite", "Disneyesque" and (from 1941) "butch", in the sense of aggressively masculine. Where would we be without him?

September 11, 2014

A small literary coincidence

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

A pleasing coincidence struck me the other day. I had just finished reading both James Salter’s novel All That Is and Jérôme Ferrari’s The Sermon on the Fall of Rome, when opening Le Monde des livres (and I promise to soon stop banging on about all things French), I came across Ferrari reviewing a French translation of Salter’s book, Et Rien d’autre. The piece was given front-page coverage and this was followed by an interview with Salter inside, as well as a short extract from the translation.

Salter’s first novel for over thirty years was garlanded with praise when it appeared in 2013 (it was reviewed in the TLS of May 31 by his near-namesake Michael Saler). The paperback edition carries admiring comments from Richard Ford (“No question, the best novel I read this year”), John Irving, Edmund White, the author of If I Die in a Combat Zone Tim O’Brien – “the best novel I’ve read in years” – and many others (should one read these comments before reading the novel or after? I prefer the latter course of action, as with an introduction). I would, uncontroversially, concur: it is a very fine novel indeed.

It’s interesting that Ferrari should have been chosen to review Et Rien d’autre (I don’t recall him reviewing for Le Monde before) as he is himself a highly praised novelist albeit much younger than Salter’s eighty-nine years; his novel (Le Sermon sur la chute de Rome) won the Prix Goncourt in 2012 and appears in English this month in a fine translation by Geoffrey Strachan (a TLS review is forthcoming).

Does Ferrari like Salter’s novel? He loves it, thereby continuing the long French love affair with the American novel (it’s worth mentioning perhaps that Salter is himself something of a Francophile). Ferrari’s own, very different, novel is terrific, too. What a rewarding experience it has been for me to read them both. O lucky man.

September 9, 2014

A TLS reviewer goes to war

By MICHAEL CAINES

He counted not the cost:

What he believed, he did.

The month before the poet Charles Péguy was killed, in September 1914, another professional writer in his forties had enlisted, in the British Army. George Calderon was initially sent to France as an interpreter. He had a "combative" interpretation of an interpreter's duties, however, and went missing in action during the Battle of Achi Baba (a bloody yet vain attempt to gain an advantage in the Dardanelles) on June 4, 1915.

Calderon's literary friends included Percy Lubbock, who published a "sketch from memory" of him after the war, and the poet Laurence Binyon, whose tribute, quoted above, adorns Lubbock's book; his wife Katharine had served as his literary agent and continued to promote his works in the 1920s, including his often revived play The Fountain. Other works included a tragedy in blank verse, Cromwell: Mall o'Monks, and his posthumously published account of the South Seas, Tahiti by Tihoti. He had also reviewed regularly for the TLS in the decade before the war, covering Russian literature, the new G. K. Chesterton or H. G. Wells, and various other subjects.

Perhaps most significantly for theatre history, Calderon had spent a few years in Russia and come back with tastes ahead of his time: his translation of The Seagull, staged at the Glasgow Repertory Theatre in 1909, was the first British production of a play by Chekhov. . . .

Unfortunately, Britain wasn't ready for something so "queer, outlandish, even silly", as a critic would say, a couple of years later, of a production of The Cherry Orchard. When The Seagull came to London for one night only in 1912, Calderon's proposed lecture on the dramatist had to be abandoned; there was virtually nobody there to hear it. The translator's view, however, was that Chekhov was a "pioneer" with a "fine comedic spirit which relishes the incongruity between the actual disorder of the world and the underlying order . . . . His plays are tragedies with the texture of comedy".

Calderon's impassioned and insightful appreciation of Chekhov still seems to me to be worth reading. I'm particularly struck by the observation with which he ends the introduction to his translations of The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard: it was wrong of the Russian critics to read a "message of substantial hope" into Chekhov's work. (While Calderon tentatively takes an alternative form of consolation from the plays, perceiving in them the promise of some other, perhaps more spiritual kind of progress, he doesn't press the point.) Each generation has such hopes, and believes it stands "on the boundary line between an old bad epoch and a good new one. And still the world grows no better; rather worse; hungrier, less various, less beautiful". That's why Chekhov puts the "hopefullest sentiments" in The Cherry Orchard in the mouth of "Trophímoff", the "mouldy gentleman" and "a fine guarantor for the Millennium!" Calderon gets what is a great, unfunny joke on Chekhov's part. "It is all his sad fun."

Less admirable, a century on at least, are Calderon's activities as the Honourable Secretary of the Men's League for Opposing Women's Suffrage – but that didn't mean he couldn't, with his reviewing hat on, mock a novel for depicting a world in which "the men talk athletics and the women culture". ("Honourable behaviour is called 'cricket'; dishonourable behaviour is 'not cricket'.") "Artist, fighter, politician, scholar, talker, playboy", as the TLS described him after the war, Calderon was complex, versatile and restless. Since his body was never recovered, the TLS reviewer of Lubbock's Sketch rather Romantically thought "It was as if he had wandered off into another sphere as unceremoniously as he wandered oft into regions of this".

A new perspective on both the early years of the war and Calderon himself is offered by Calderonia, a blog recently begun by one of Calderon's successors as a champion of Chekhov, Patrick Miles. Dr Miles's biography of Calderon is due to be published next year, but, for the moment, he's made it possible to follow the day-to-day thoughts of a biographer on his subject's final year – on, say, the difficulty of appreciating Edwardian terms of praise (they can sound somewhat underwhelming today) or on the various military manoeuvres and blunders that were to decide Calderon's fate.

Miles also gives a selection of thirty amusing and representative quotations from Calderon's work ("Tolstoi is, above all things, a good hater . . ."), and poses a question that applies to many of his contemporaries: why did Calderon go at all, when, at his age, he didn't "need" to and "his literary career was at full throttle"? The frank answer is: "We shall never entirely know . . .". "I'm off on a new and unknown adventure", he wrote to Katharine in the month before his death, "but it either ends ill or very well, and no thought can alter it – so rejoice in the colour and vigour of the thing." Swashbuckling spirit and patriotism aside, however, there is a suggestion of a deeper explanation in something Calderon wrote in the TLS, in a review of Maude Aylmer's "enormously prolix" biography of Tolstoy. Here he rejects "Tolstoyism" as "an exaltation of the merely animal side of life":

"It seems so important to Tolstoy for men to have enough to eat and for there to be no pain or violence, that he is ready to sacrifice all ideas in the world for that end; patriotism, art, science, philosophy, poetry – everything may go to the Devil that Christian brotherhood may reign; and this Christian brotherhood amounts only to helping one another to live the dull material life, like green-flies in a fat garden."

For Calderon, as much as he admires Tolstoy as "one of the great figures of the age", this is not a "doctrine . . . for this generation". The ideas he mentions are, presumably, protected and nurtured by the apparatus Tolstoy would dismantle: "government, law, war, frontiers, and nationality". Not only patriotism (a very ugly thing, to my mind) but art and even poetry are apparently worth dying for. "War may be murder, but it is so many things besides that it is not worth stopping to call it names."

That was George Calderon writing in 1910. I wonder if he held to those views after seeing action in Flanders (where he was wounded) and at Gallipoli.

September 8, 2014

Hackney's little revolution?

Clare Perkins, Alecky Blythe, Imogen Stubbs and Ronni Ancona in Little Revolution © Marilyn Kingwill

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Truncated jeans, exposed ankles with no socks and oversized plastic-rimmed glasses: it’s a familiar sight in Hackney. It’s also the uniform of white, middle-class Tony, one of the central characters in Alecky Blythe’s new “verbatim” play, Little Revolution, which has just opened at the Almeida Theatre. The play’s text is generated from interviews with real people that Blythe recorded on her dictaphone during the London riots in 2011, after the shooting of Mark Duggan by the police in Tottenham. On stage, the actors are fed Blythe’s edited recordings through earpieces. Their performances, in effect, are impressions; they copy accents, intonations, stutters, speech patterns. (No surprise, perhaps, that the impressionist Ronni Ancona is on the cast list.)

Blythe puts a caricatured version of herself into the story. We hear her voice booming, “I make documentary plays. Can I talk to you?”, as the “community chorus” – thirty-one volunteers from Hackney and Islington, who play hooded looters clutching booze and packets of crisps, bemused and scared bystanders, and police – rush across a rough set made of plywood, scaffolding and strip-lighting. Some stop to tell Blythe (and us) what’s happening on Mare Street, for example, and their opinions on the crisis. “You can’t smooth over inequality.” “When you live in London you never thought these kind of riots will come to you.”

The director Joe Hill-Gibbins has reconfigured the auditorium so that it’s in the round, to feel like we’re also witnesses to the action. Even before the play begins, cast members are positioned within the audience, talking in groups, while R&B and hip-hop pumps in the background – no different from the theatre’s bar outside. (Eminem’s “Rap God” is particularly well chosen: ““Something's wrong, I can feel it / Just a feeling I've got / Like something's about to happen / But I don't know what / If that means, what I think it means, we're in trouble / Big trouble”.)

But the main focus of the play is on the people to the side of the chaos. Tony and his hippy wife, Sarah, have started a fund, along with other residents living around Clapton Square, to help a local shopkeeper, Siva, repair his looted premises. They host a balloon- and bunting-adorned tea party sponsored – of course – by Marks and Spencer. (“Free cake? Is it to attract the looters? They like free things”, Colin, a philosophical Afro-Caribbean barber, comments when he hears about the event.) At one point, Tony hands Siva a mug of tea: “without any irony, you get the ‘I heart Hackney’ one”. And Sarah has made red gingham “steward” armbands for the organisers to wear. She’s slightly concerned that she’s coming across on the dictaphone as “so white middle-class”; Blythe responds, “don’t worry, I won’t stitch you up” – which is presumably exactly what has happened.

A couple of streets away, mothers on the less well-off Pembury council estate have set up their own campaign (Stop Criminalizing Hackney Youth), and accuse the Clapton Square group of jumping on the bandwagon: “It’s not their story . . . some people talk about it and some people live it. We actually live it”.

There’s a sense of social divide in the area, and this is the real issue the play tries to explore. Yet the riots, and the reactions Blythe has captured, are from three years ago (a brief epilogue sees her return to Colin, the barber, at the climax of the Mark Duggan inquest in January 2014, but Colin is unaware it's happening until prompted). Has anything changed since the riots? What’s the Hackney community saying now? That’s what I want to know.

September 5, 2014

Charles Péguy, early victim of the Great War

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“Charles Péguy was surely a hero. He represented all the qualities of the Republic. Born into a peasant family, with a grandmother who could neither read nor write, he made his way to the École Normale Supérieure. He was the author of many works, including a gigantic attempt to produce a Christian Iliad. He defended Dreyfus. He opposed anti-Semitism. He exalted Joan of Arc. He went into battle in August 1914 singing “ça ira” and was killed by a German bullet at the age of forty-one. If ever a man stood for both Revolutionary and Catholic France, and was a model of honesty and courage, it was surely Péguy.”

Thus wrote the late Douglas Johnson in the TLS in 1992, in a review of a book by the philosopher Alain Finkielkraut on the poet, dramatist, fiercely anti-bourgeois polemicist and publisher who was killed a hundred years ago, on September 5, 1914 – on the first day of the battle of the Marne. If one thinks also of (the very different) Apollinaire, wounded in combat and who died of those wounds in 1918, then it can be said that France had its war poets too.

Péguy was a committed and radical socialist who later became a fervent, mystical Catholic. Much of his work appeared in the Cahiers de la quinzaine, which he set up in 1900: the polemical works Notre Patrie (1905) and Notre Jeunesse (1910), which reflects on the effects of the Dreyfus affair – “des anciens dreyfusards, des nouveaux dreyfusards, dse dreyfusards perpétuels, des dreyfusards impénitents, des dreyfusards mystiques, . . .”gives a flavour of its rolling cadences. Joan of Arc, meanwhile, was at the heart of his poetic project – the lengthy meditation on the Passion of Christ that is the trilogy of dramatic poems Le Mystère de la charité de Jeanne d’Arc (1909), Le Porche du mystère de la deuxième vertu (1912) and Le Mystère des saints innocents (1912), in which near-hypnotic repetition – “Elle pleurait. Elle pleurait. Elle fondait. / Elle fondait en larmes . . ." creates a strong sense of momentum.

Joan of Arc is both a victim and the powerful conscience of the nation. Péguy’s deep patriotism and love of tradition are reflected in the lines “Reims, vous êtes la ville du sacre. Vous êtes donc la plus belle ville du royaume de France". The fact that Reims was the cathedral where the kings of France were crowned shows how far Péguy had moved from his early socialism. And it’s surely hard for an English reader to take in the following without flinching: “C’étaient des barbares, . . . infiniment plus barbares, infiniment pire que les Anglais mêmes". The English being referred to here are, of course, Joan of Arc's executioners.

Poetry was also where the married Péguy was able to allude to the deep, unconsummated love he felt over many years for a young woman, Blanche Raphaël: “Quand une fois cette parole a mordu au coeur / Le coeur infidèle et le coeur fidèle, / Nulle volupté n’effacera plus / La trace de ses dents”. Elsewhere he refers to the unhappiness brought on by the fact that he wasn't able to have his three children baptized because his wife Charlotte-Françoise was a non-believer: "Leur front bombé, tout lavé encore et tout propre du baptême, / Des eaux du baptême".

Péguy’s Oeuvres poétiques was published in Gallimard’s prestigious Pléiade series in 1941, just ten years after the imprint was founded; at least three volumes of prose works have appeared in the Pléiade since. In the TLS, George Steiner wrote a blazingly eloquent review of the third volume, in which he talked of how “the material productivity of the man has few parallels in the history of literature”. Steiner concedes that the poem Ève (1913) is “interminable”, but he goes on to say that it’s “charged with a tenacity of vision, with an investment in rebirth . . .”. The poem contains the famous, portentous lines: “Heureux ceux qui sont morts pour la terre charnelle, / Mais pourvu que ce fût dans une juste guerre . . . . / Heureux ceux qui sont morts dans les grandes batailles, / Couchés dessus le sol à la face de Dieu . . .". Steiner’s article, like Douglas Johnson’s, curiously also appeared in 1992. Péguy has scarcely been mentioned in the TLS since (there was a passing reference to Geoffrey Hill’s The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Péguy in John Kerrigan’s recent essay on Hill, TLS, August 8).

Which prompts the question: has any major French writer fallen victim further to the dictates of literary taste and fashion than Charles Péguy? I sense that he’s not much read today and this notion was confirmed in the course of visits to three bookshops in London: the two French bookshops in that Gallic oasis, South Kensington, and the well-stocked European bookshop off Regent St. None of them had any books by Péguy in stock. Not one. Yet Notre Jeunesse certainly remains a powerful work, and the poetry continues to have its advocates. As if in support of this, Gallimard are bringing out a new Pléiade edition of the poems in November: “Il est temps de redécouvrir sa parole juste”, the publishers write.

Cover of Die Aktion with Péguy's portrait by Egon Schiele (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

According to his biographer William Carter, Proust, who was Péguy’s contemporary, “expressed his admiration for Péguy’s heroism but not for his writings”. Meanwhile, another contemporary, André Gide, wrote in his Journals, April 1941: “That Péguy is a great figure, and particularly noble and representative, goes without saying; I consider admirable his very life and many a page of his Jeanne d’Arc, as well as numerous others scattered throughout his Cahiers. But those lines from Ève which are quoted everywhere today . . . belong among the worst I have read . . .”.

The TLS published a tribute to the fallen poet in November 1914: “. . . This was Péguy’s firm conviction; no duty so important as the military duty! When the war broke out, man of forty as he was and father of a struggling family – man, too, much engrossed and overworked by his triple occupation as poet, prose-writer, and publisher – he changed from the Territorials into a regiment sent on active service to the front”.

This was written by the poet and critic Mary Duclaux (1857–1944), whose "Belgia Bar-Lass" (1914) was a TLS Poem of the Week last year.

September 4, 2014

Word aversion

By DAVID COLLARD

The concept (new to me) of Word Aversion is described by the linguistics professor Mark Liberman as:

“A feeling of intense, irrational distaste for the sound or sight of a particular word or phrase, not because its use is regarded as etymologically or logically or grammatically wrong, nor because it's felt to be over-used or redundant or trendy or non-standard, but simply because the word itself somehow feels unpleasant or even disgusting.”

According to Liberman, common words prompting revulsion include not just the obvious ones such as “puss” or “ooze” or “scab”, but also “squab, cornucopia, panties, navel, brainchild, crud, slacks and fudge” (these last four surely constitute the name of an advertising agency). As it happens I have an intense and perhaps cranky loathing for a particular word which we'll come to in a moment, a word used frequently by a character in the latest Martin Amis novel, The Zone of Interest (which I’m told will be reviewed in the TLS of September 19).

In his novel, Amis explores the spacious literary terrain between Joseph Heller and Primo Levi, featuring a malign nonentity of a concentration camp commandant by the name of Paul Doll. Amis has given this functionary an idiolect that is immediately recognizable and unsettlingly familiar: a complacent middle-management register, a chortling, affably pedantic, utterly reasonable tone that reminds me of certain of today’s public figures. Doll is, Amis insists rather too often, “a normal man with normal needs”. His worldview is expressed in pompous, pedantic and leaden aphorisms: “I also find that Martell brandy, if taken in liberal but not injudicious quantities . . .”, or “one can’t ‘go mad’ and throw the money around as if the stuff ‘grew on trees’”. Those pincer-like inverted commas tell their own story. But if there's one word that pins him down it’s the word I’m most averse to:

“Whilst she could clearly see she had shaken me to the core . . .”

“. . . whilst the luggage was stacked near the handcarts . . .”

“Whilst I can take a joke as well as the next man . . .”

And so on. Amis has chosen well in choosing “whilst”.

“Whilst” is a word that never fails to irritate me, not simply because it’s an unnecessary and unattractive alternative to “while”, but because it’s employed as part of the pervasive culture of “customer care”. Here are three examples gleaned on a quick stroll around my neighbourhood this morning:

“This car park is reserved for customers whilst using the bank.”

“We apologise for any inconvenience whilst work is in progress.”

“Please wait here whilst your order is being processed.”

And a very familiar recorded telephone message: “Please hold the line whilst we try to connect you”.

American readers will find “whilst” merely quaint, and possibly affected, but on this side of the pond there's a terrible tendency to prefer “whilst” to “while”, especially in public notices. It's not simply that “whilst” is outdated, it comes with a certain hidebound attitude – prim, supercilious, self-righteous.

Compare the not-unrelated words: “amongst”, “betwixt”, “unbeknownst”.

Especially “unbeknownst”. They all share – for me at least – a false Arthurian whiff, a saloon-bar, fake bonhomous resonance, something that implies thoughtful reflection and careful discrimination and eloquence but usually expresses the opposite. (I am relieved to be informed by the editors at the TLS that the “st” of “whilst” and “unbeknownst” are dropped as a matter of house style – and that “betwixt” is never used, on pain of summary sacking.)

Perhaps I am too sensitive. But then as Professor Liberman points out, word aversion isn’t rational. If you’re wavering about usage, the advice from Wikipedia is reasonable enough, and runs thus:

“If you’re unsure which to use, choose ‘while’ (especially if you're an American).”

Or, if you prefer: don’t use “whilst” unless you want to sound like a camp commandant in a Martin Amis novel.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers