Peter Stothard's Blog, page 36

November 10, 2014

Enough of a good thing

Magwich; one of Ellie Foreman-Peck's illustrations for The Pigeonhole edition of Great Expectations.

By ROZ DINEEN

Dickens, of course, wrote and published in instalments. Hard Times, for example, first appeared incrementally in a weekly magazine, between April and August 1854. Oliver Twist was monthly. As we know, this method made its mark on the author’s work – Dickensian doorstoppers are scored with frequent, gentle re-introductions, regular cliff hangers, and casts of characters whom forgetful monthly readers are prompted to recognize thanks to those Dickensian shorthands and props. The audience even attempted to influence the author between instalments. During the composition of The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens wrote:

“I am inundated with imploring letters recommending poor little Nell to mercy.– Six yesterday, and four today (it’s not 12 o’Clock yet) already!”

Dickens’s ways may have been popular but they weren’t always appreciated. Reviewing The Immortal Boz: The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster, in the TLS on October 5, 1911, Thomas Seccombe wrote this:

“Dickens’s books certainly bear every trace of their undisciplined bringing up. They are singularly formless . . . Condense the plot of almost any one of Dickens’s three-deckers and it will be found to read like a depraved nightmare.”

Let’s let Seccombe continue here for a moment:

“The general indictments brought against Dickens are familiar to everyone. Many of his rhetorical devices, it is said, are odious, his attempts at fine writing almost invariably absurd, his pathos nauseous, his wit third-rate, his historical conceptions ignorant and puny, his technique archaic . . . . He thinks you never can have enough of a good thing.

His unit is not the book but the monthly part. He is a monthly entertainer who has to utilize every ounce of energy that he possesses in developing his idiosyncrasy and multiplying his personality.”

Just 103 years and about a month later and it would appear that we are surrounded by people who think you never can have enough of a good thing.

Glance just now around your train carriage, or waiting room, or café and I am sure you will see many more scalps than foreheads. Which is to say that everyone around you is looking down towards their phone, unable to get enough of what they find there.

According to a new survey by Publishing Technology, many of these people are even reading books. 43 per cent of those surveyed had read “part of” an e-book on their mobile phone. 23 per cent of eighteen to twenty-four year olds use their mobiles to read books on a daily basis.

The provision to do so has been around for some time. DailyLit sends books by section to your phone or e-reader, “Don't want to carry Anna Karenina on the train? DailyLit sends you just enough for your morning commute or coffee break.” They have already delivered over 50 million instalments. Or there’s the Kindle, the Kindle app and all the other variations on a theme of e-reading.

But these just present whole novels in bits – so it will be interesting to see how people take to The Pigeonhole a new website and app, which seems to realize the potential of phone reading. The Pigeonhole is beautifully designed, and whether used on a big or a small screen it provides a pleasurable and aesthetically modern reading experience – but that’s a side point: the main thing is that The Pigeonhole, rather than simply representing whole novels in commuter-friendly chunks, offers reading matter that is designed, like Dickens’s regular instalments, to be read in bits, or as the Pigeonhole so elegantly calls them, Staves.

As in Dickens’s day, readers can provide feedback to the authors as they write. There are discussion boards for the readerly community. And add-ons that take full advantage of the format: The Pigeonhole’s first novel, Redpoint by Yseult Ogilvie, comes with author interviews, a photo journal of the protagonist’s journey, a soundtrack. So far The Pigeonhole has hosted long-form essays, sex staves and, of course, Great Expectations, by the man himself, delivered as it originally was, in instalments, staves, episodes, with illustration. It’s meant to be a social reading experience, in which we read together and then we wait, together, anticipating together . . . Is this, like Birkbeck College’s ongoing experiment with reading Our Mutual Friend month by month, as it was in 1864–5, another sign of our renewed interest in old reading habits?

We will have to wait and see, based on the success of The Pigeonhole and apps like it, if all those bowed heads really are busy reading.

November 7, 2014

Jean-Philippe Toussaint – website extraordinaire

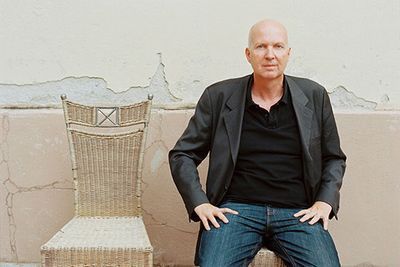

Jean-Philippe Toussaint, 2012. INTERFOTO / Anita Schiffer-Fuchs/Writer Pictures

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Are writers’ websites worth looking at? I only ask because I’ve only ever knowingly consulted one: that of the Belgian novelist and filmmaker Jean-Philippe Toussaint. I had read somewhere that it was something out of the ordinary – indeed it is.

Toussaint, who was born in 1957, is the author of ten novels, none much more than 200 pages in length, all of them published by the distinguished Editions de Minuit. The most recent, Nue (2013), made up the final part of a four-volume sequence (“tetralogy” would be too grand a term in this context) chronicling the troubled affair between the narrator and Marie. The third volume is called La Vérité sur Marie (2009) and was published in English by the Dalkey Archive Press as The Truth about Marie. (Dalkey have published eight of the books.)

Toussaint is both a fine stylist and a good storyteller – a rare enough combination perhaps. His books convey a sense of effortlessness, but it's clear that a lot of effort has gone into their composition. He excels at set pieces, several of which are firmly imprinted in my mind: descriptions of forest fires on a Mediterranean island, of a panic-stricken thoroughbred trying to break out of the perimeter at Tokyo airport during a fierce thunderstorm, of a motorcycle chase through the back streets of Shanghai . . .

The TLS has followed Toussaint’s career with interest and admiration from its beginnings in 1985 when he brought out the quirky novella La Salle de bain (Bathroom). In fact, the only publication of his we didn’t review was his 26-page pamphlet La Mélancolie de Zidane, about the captain of the French football team’s headbutt on the Italian defender Materazzi in the World Cup final of 2006 in Berlin – an act that brought down the curtain on an illustrious career in an abrupt manner.

Toussaint’s website is impressive. The homepage consists of a map of the world, with flashing lights alongside the names of certain cities: if you click on Tokyo you get a list of his publications in Japanese (Toussaint’s work has been widely translated). Tokyo is also one of the destinations on Marie and her lover’s itinerary, as a little aeroplane indicates! And there are links to various interviews with the author.

If you click on the titles appended to the map you find all sorts of further information, from a log detailing the progress of a manuscript – October 2008 to end of July 2011; below that we have “Plans, Variantes, Débris [fragments]”, and underneath that draft, notes and sketches, the latter including the layout of a cemetery that the author obviously had to get down on paper in order to properly visualize it. Has any novelist revealed his working methods to this extent?

It would be easy to spend hours on this website. The last thing I looked at was a 93-minute film of discussions in Paris earlier this year between Toussaint and three of his translators, including his Japanese translator Kan Nozaki who points out that the author’s work has been appreciated in Japan from the outset. It's a body of work that deserves to be better known in the anglophone sphere.

November 6, 2014

Ivor Gurney’s recovery

By MICHAEL CAINES

As I mention in the latest episode of TLS Voices (embedded above), the Gloucester-born Ivor Gurney is an odd case among the war poets. . .

His first collection, Severn and Somme, appeared in 1917, while he was still a private with the Gloucesters, and the TLS, among other papers, welcomed it warmly. A second book, War's Embers (1919) seemed just as good in places, although prone to incoherence. The same TLS reviewer, Harold Hannyngton Child, thought some of it was journalism rather than poetry – although that didn't stop Child (presumably) recommending Gurney to write for the paper. Unfortunately, Gurney's publisher rejected a third collection, and in 1922 he was confined to a mental asylum, where he nonetheless continued to write both music and verse prolifically.

Posthumous reconsideration of Gurney's work has been gaining ground for some time, but only now is the great mass of unpublished material being edited as a whole for scholarly publication. One of Gurney's editors, Tim Kendall, writes about this Gloucestershire poet's woeful decline and astonishing creativity in this week's TLS, by way of an introduction to six previously unpublished Gurney poems. I've also chosen two of them to read as part of the episode above. They confirm for me a sense that this confined survivor of Ypres – one who was besotted with Beethoven and King Lear, the Cotswolds and nocturnal walks – had a great post-war battle to fight in the mind, a then-secret counterpoint to the published prose recollections of Robert Graves, the "strange clarity and dramatic suppleness" of In Parenthesis, and all the rest.

Round and round goes Gurney in his war-inspired verse, recasting "First Time In", mapping peaceful scenes behind the lines in French villages with memories of England, turning in his anguish from sing-song quatrains to not-quite-verse anecdotes – although, to be fair, his awkward unwillingness to revise away rough edges was apparent from the start. He thanks the music historian Marion Scott in Severn and Somme for helping to see his poems into print "in spite of my continued refusal to alter a word of anything" – and H. H. Child recognized that with opening lines such as "Wakened by birds and sun, laughter of the wind", some of Gurney's "metrical practices" were unlikely to "find favour with pedants". To the critic's mind, it didn't matter: "The 'general' reader will nearly always recognize Mr. Gurney's purpose in scrambling or dancing, instead of marching". A later editor, P. J. Kavanagh, thought him flawed but "good at the short sprint, the poem expressed in two or three breaths", and a master of first lines, "splendid beginnings". Others might tip the balance the other way, putting before the impressive moments what Mick Imlah once dryly characterized as Gurney's "variable coherence".

As Sean O'Brien notes, Gurney can be "technically at sea"; the phrase that appears in the course of these reflections on the past twelve months of books relating to the war poets. Yet one of those books is an anthology edited by Kendall in which Gurney receives as much space as Graves and Edward Thomas combined. (I mentioned this anthology, Poetry of the First World War, on this blog late last year.) Compare that newfound prominence with one striking symptom of Gurney's marginalization almost half-a-century ago: Roy Fuller, in his role as Oxford Professor of Poetry, could devote a whole lecture to the poetry of the two world wars and not mention Gurney at all.

But since then? Well, in 1985, his name was included in the memorial to the war poets in Westminster Abbey, and in 1995 an Ivor Gurney Society was established to promote interest in both his music and his verse. There have been biographies, collections of letters and much-expanded editions of the poems. In my copy of an anthology from the 1990s, I see that "To His Love" has crept in, amid the many Sassoons and Owens, albeit framed by mini-bouquets of vile poppies.

Ours is an "absent-minded" culture, Michael Schmidt suggests in his Lives of the Poets, and Gurney is one of those who was, for a time, left behind. But here he is again, in some sense recovered, faults and all – "Men delight to praise men", as he wrote in one of those masterly opening lines.

November 5, 2014

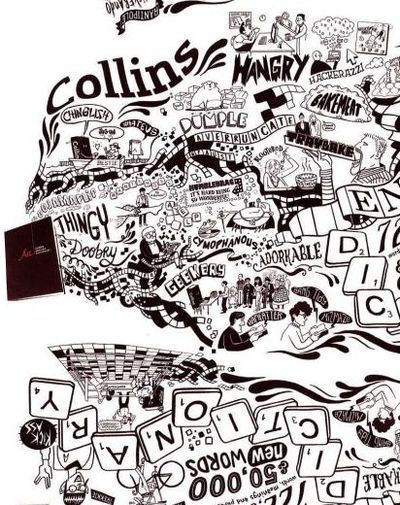

Wamblecropt, nurdle, autumn and other favourite words

By CATHARINE MORRIS

“The great thing about a dictionary”, said Mark Forsyth – the author of The Etymologicon (2011), among other books – at the launch of the new Collins English Dictionary at Waterstones Piccadilly a couple of weeks ago, “is that you can start anywhere and finish anywhere”. “I go to a dictionary to look up a particular word and I find – ah yes, ‘Agnate’ means ‘sharing a common male ancestor’ or whatever it happens to be and then my eye just sort of drifts, so I discover that there’s a word ‘aglet’ meaning the small bits of plastic on the end of your shoelaces . . . and then my eye drifts further and further and further and eventually I come to look at my watch and discover that it’s February”.

The theme of the evening was favourite and least favourite words (the TLS contributor David Collard has written very entertainingly on the topic from an aesthetic point of view; you can find his blog posts here and here). Our host, the journalist Lucy Mangan, asked Forsyth, who provided the introduction to the new dictionary, what qualities he looked for in a word. “It’s wonderful when a word means something very, very specific . . . like ‘gongoozle’ – I remember finding that in a dictionary of canal terminology . . . . Gongoozle means ‘To stare idly at a canal or other watercourse and do nothing’ . . . . I have since discovered that it is still extant in the houseboat community”. He also offered “sprunt”, used in the Roxburgh district of Scotland in the early nineteenth century, which means “to chase girls around among the haystacks after dark”; and “mamihlapinatapai”, used by the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America, which he defined as “two people looking at each other both wanting to do the same thing but neither wanting to be the person to do it”. (When Mangan said that it should be a British word, Forsyth agreed: “It describes every kiss I’ve ever had”.)

Forsyth is attracted by the sound of certain words. He loves “wamblecropt” (“overcome with indigestion”) and “snollygoster” (which means "dishonest politician"), “a nineteenth-century American word which has since died out because all politicians are now honest”. Then there are the “lovely etymologies”. Forsyth is keen on “ultracrepidarianism”; this he defined as “giving opinions on things you know nothing about, which I do professionally”. The OED says of ultracrepidate: “Etymology: the Latin phrase ultrā crepidam ‘beyond the sole’ in allusion to the reply of Apelles to the cobbler”. I had to look up Apelles and the cobbler. Apelles is the artist Apelles of Kos (fourth century BC), and the story goes that, having overheard a cobbler saying that a shoe in one of his paintings looked wrong, Apelles repainted it; but when, buoyed by this little triumph, the cobbler moved on to criticize other parts of the painting, Apelles was incensed: “The cobbler should go no further than the shoe!”

Mangan had spotted the word “nurdle” on Forsyth’s website. A nurdle is the small amount of toothpaste you squeeze on to your toothbrush. “In the toothpaste industry, the nurdle is a big thing”, Forsyth told us. He described a court case involving two toothpaste manufacturers that was “all about nurdles and the depiction of nurdles” on the toothpaste packaging. “The word ‘nurdle’ cropped up several hundred times in the court papers.” No mention of the toothpaste nurdle in Collins; but it does give the cricketing term: “To score runs in cricket by deflecting (the ball) rather than striking it hard”.

The least favourite words mentioned during the discussion were in fact least favourite usages. Forsyth hates the use of the word “individual” to mean “person”; and “real” in phrases such as “real people” and “real life”: “‘Real life’ merely means my life and the lives of my friends and all the people I speak to down the pub”. The audience chipped in with the phrase “common sense” and “like” as a filler word. (“I think ‘like’ gets a slightly bad press”, Forsyth said; “we all use filler words . . . . ‘I mean’ and ‘well’ are the ones used by the older generation. ‘Like’ is used by the younger generation.”)

One favourite word (submitted via Twitter) was “Autumnal”, which prompted Forsyth to share “petrichor”, a new addition to the Collins dictionary, which is defined there as “a sweet smell that is produced when rain falls on parched earth”.

When people talk about favourite words, Forsyth observed, they tend to choose obscure rather than normal ones. This reminded me of the poem “At The Pillars” by Hugo Williams, written in memory of Mick Imlah, which was published in the TLS at the beginning of this year:

Everyone was saying their favourite word.

Yours was “suddenly”.

Other members of the herd

chose something funny or absurd,

“lackadaisical” or “haphazard”.

We were laughing and drinking happily,

saying our favourite word.

Yours was “suddenly”.

November 3, 2014

Steven Pinker on good – and bad – writing

Above: Steven Pinker; Nick Cunard/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

“Why is so much writing so bad?”, Steven Pinker asked recently, at an Intelligence Squared event with Ian McEwan at the Royal Geographical Society in Kensington. (The event was filmed, and the video can now be watched online here.) He’s not convinced, as some people are, that bad writing is a deliberate choice – as in the case of "academics in softer fields" who try to compensate for a lack of substance by "spouting highfalutin gobbledegook" – or that it came in with digital media. “Bad writing has always been with us . . . in every decade . . . going back to the invention of the printing press."

The abundance of bad writing, Pinker said, is testimony to the fact that writing is inherently difficult: it involves pretence and "a great deal of craftsmanship". For the past two decades Pinker has been in the business of expressing complex ideas for a wide readership, and many of those ideas have been about language itself, so he has a "dual interest" in the subject of good writing. In researching it, he asked a number of respected authors what style manuals they read when they were learning their craft, and "every last one" gave the answer "None". What they all had in common was “immersion in the world of edited prose . . . . Every great writer has spent an enormous amount of time consuming the prose of others”. And it’s “good reading, not simply reading”: dwelling on it; taking in idioms and paragraph structure; studying particularly striking or moving passages and trying to “reverse-engineer” them.

Good writers also adopt the right mindset. Writing is not like spoken conversation, Pinker pointed out – you're not "guided by the give and take of face-to-fact contact . . . . You’re casting your bread on to the waters”. Not only that, but “you may be dead when they read it”. There are different styles for different scenarios, of course, but Pinker advocates the “classic” style set out by Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner in Clear and Simple as the Truth in 1994. There is more about the classic style to come in the TLS review of Pinker’s new book The Sense of Style, but I can say here that Pinker recommends it over the reflexive style, according to which “the writer struggles to externalize some kind of subjective, idiosyncratic and mostly ineffable personal reaction to events”; the oracular style (“the writer sees something that no one else can see and announces his vision to the world") and the self-conscious style, where "the writer's chief goal is to escape accusations that he's naive about the epistemological assumptions underlying his own enterprise" (such writing, said Pinker, is often “larded with apologies”).

Use examples, Pinker said, and show rather than tell. And learn something about syntax – there is much to be gained by being able to identify a subordinate clause, a modifier, or an adverb; to put your finger on what is wrong with a sentence. Understanding grammar will also enable you to fight back, to defend your writing when an editor would like to change it. There is another aspect that is crucial: coherence. Pinker’s advice is to craft at the level of the paragraph, of successive sentences. Think about the narrative arc, avoid choppiness and help the reader to keep track of all the players.

Pinker went on to talk about usage debates. Is it all right to use "aggravate" to mean “annoy”? What about fused participles (as in "I object to Sheila leaving" as opposed to "I object to Sheila's leaving"), or the singular "they"? (Pinker gave the example of President Obama's statement "No American should ever live under a cloud of suspicion just because of what they look like".) Pinker deems prescriptivist versus descriptivist to be “a false dichotomy"; the main thing, he said, is to be sensitive to the expectations of the audience you are writing for. In a side note he pointed out that editors of dictionaries are not arbiters; they pay attention to how people use the language: "The lunatics are running the asylum . . . . [And] this is not a new development in the writing of dictionaries”. But he also said that you should be careful when using “fancy schmancy” words such as “fulsome” and “meretricious”.

When McEwan asked Pinker about his scientific background, Pinker replied that he liked to approach usage as an empirical matter (what’s the evidence that you can’t split an infinitive? and so on); and style as an exercise in applied psychology. Writing should convey information and please the ear. “Put the heavy stuff at the end of the sentence", polysyllables after monosyllables. ("It's 'kit and caboodle', not 'caboodle and kit'.") Good prose, he said, is enlivened by moments of poetry: alliteration, assonance, allusion.

McEwan brought up the vexed question of the use of the word “hopefully” in phrases such as “Hopefully it won’t rain today”: “set us free”. It’s a curious rule, Pinker replied, because there are many other comparable adverbs (“frankly” and "sadly" among them) that are freely used to convey the attitude of the speaker. But "hopefully" used in that sense came late, in the 1930s, so it grated on the ear.

"As the composition of the literate readership changes it ceases to be a problem." He gave the example of the verb "to contact", which was frowned upon by William Strunk Jr. and E. B. White in The Elements of Style. "This controversy is long forgotten . . . . ["Contact" as a verb] went viral . . . and now it is unexceptionable . . . and precisely because it's sometimes indispensable." "Change is inexorable", Pinker said; "resistance is futile".

October 31, 2014

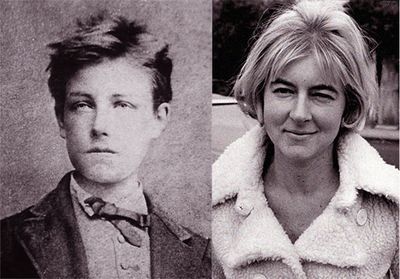

Did Rimbaud and Tonks really ‘disappear’?

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Rosemary Tonks in 1969; Photo: Associated Newspapers/Rex Features

Poets can be business-minded and highly sociable. They can live long lives. Many people will deny it, but that’s nothing new. At Wednesday night’s Poet in the City event at King’s Place, N1, a gathering – which included Tim Matthews, Professor of French and Comparative Criticism at UCL, the poets Matthew Caley and George Szirtes, and Neil Astley, Editor of Bloodaxe Books – took as its premiss the “strange disappearance” of Arthur Rimbaud in 1879 and, a hundred years later, that of the British poet and novelist Rosemary Tonks. Both were descendants, more or less directly, of Charles Baudelaire, chronicling their urban spleen; then, they “vanished”. This was, our hosts told us, a “great literary whodunit” . . . .

Except that the perpetrators were not only known from the outset, they were known by the poets themselves. It was, in fact, the poets whodunit: for Rimbaud, to renounce poetry in favour of trading coffee, arms – and some think, slaves – in the Horn of Africa, was, as Paul Verlaine later put it in Les poètes maudits (1884), “logical, honest, necessary”. Rimbaud had said as much himself in the mid-1870s, when, squatting in London, he wrote “Départ”: “Assez vu…/ Assez eu…/ Assez connu….”.

Tonks, too, had signed a confession years before swapping London for Bournemouth, in her poem “The Sofas, Fogs and Cinemas”: “All this sitting about in cafes to calm down / Simply wears me out . . . . / I have lived it and I know too much”; she was, she said, “psychologically smashed”. (This frazzledness was conveyed on the night by the actress Lucy Tregear, whose readings of Tonks, in the style of Emma Thompson directed by Richard Curtis, clearly channelled the Bodley Head’s assessment of Tonks’s novel The Bloater (1968) as “the more than half-serious dilemma of whom to choose as a lover”.)

A whiff of mystery, literary exile or, as Verlaine had it, damnedness, can, of course, help to generate interest – Tonks’s Collected Poems, published by Bloodaxe, was launched last night and will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS – but it can also obscure the granular detail of a life lived, in the case of both poets, to the full.

Both Rimbaud and Tonks wrote every day – lists and diary entries for the most part (“more Beckett than Byron”, said Matthew Caley), and, in Rimbaud’s case, there are letters a-plenty – just not ones addressed to the literary establishment. Astley, who wrote Tonks’s obituary for the Guardian earlier this year, had her living by the sea as “the reclusive Mrs Lightband”. (One could be forgiven for thinking it a pseudonym adopted after her rebirth in the 1970s as a fundamentalist Christian; it was in fact her marital name, kept in spite of divorce.) He had repeatedly attempted a correspondence with the poet, hoping to persuade her to reissue her poetry; only after Tonks’s death, when he read her assiduously written diary, did he learn that, on receiving a card from him in 2009 (alerting her to BBC Radio 4’s feature on her, “The Poet Who Vanished”), she had noted in her diary: “Second postcard from Satan.” What would she think now?

Astley revised his portrait following the discovery that Tonks was, in fact, pretty active up until the last, enthusiastically handing out Bibles and travelling to London to step up to the box at Speakers’ Corner. (An updated version of his Guardian piece appears in the Bloodaxe edition.)

As for Rimbaud, Szirtes’s explanation that the poet had “peaked . . . had covered all the opportunities available to him” is arguable, to say the least. Tonks perhaps came closer to the truth when, writing on Colette in the NYRB in 1974 (her last published piece), she said that Colette couldn’t write straightforward novels because they “might very likely have seemed to her not truthful enough to what was all around her”. Both Tonks and Rimbaud would have been aware that “There is the danger, in finding one’s ultimate reach in literature, of losing the original talent with which one set out” (Tonks on Colette again).

As for the common desire to see poets as hovering precariously on the brink of disappearance – be it a social, financial or physical wasting away – perhaps it all comes down to Caley’s comment towards the end of the night’s proceedings that “most modern poets would love to be noticed if they disappeared”.

October 29, 2014

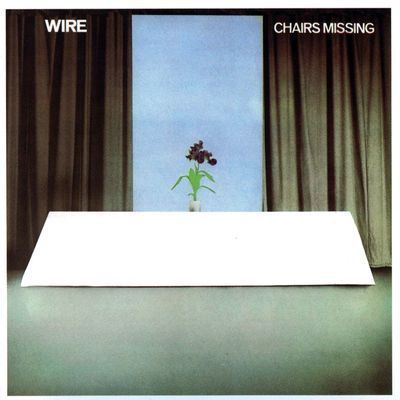

Alternative jukebox

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Here’s an unlikely publication. I say unlikely because the book is published in conjunction with BBC Radio 6 Music, the station that four years ago was earmarked for closure on account of its modest listening figures (690,000, which doesn’t seem too bad to me). There was a public outcry – false economies etc – and the station was saved.

BBC Radio 6 Music’s Alternative Jukebox (304pp. £20), put together by the station’s presenters and editors, has the air of a celebration of this last-minute stay of execution. Dipping into this handsomely illustrated volume, subtitled “500 extraordinary tracks that tell the story of alternative music”, feels a bit like a trip down memory lane, to the 70s and early 80s (and just another manifestation, perhaps, of my inexorable regression to a second adolescence).

The 60s draw to a close with the likes of “All Along the Watchtower” by the Jimi Hendrix Experience (“this radical cover of a Bob Dylan song”) and the Rolling Stones’s “Gimme Shelter” (“arguably . . . both song and album are as much a requiem for the Rolling Stones as an era-defining creative force rather than a hugely commercially successful band”). By the early 70s we have Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” and The O’Jays’ “Back Stabbers” (“As the 1960s rolled into the the 1970s, against a background of the Vietnam War and Watergate, it seemed the underlying emotion in protest soul music was paranoia”).

In the mid-70s we come across David Bowie’s baffling but wonderful “Station to Station” (a thesis on its lyrics awaits), the Stranglers’ “(Get A) Grip (On Yourself)”, the Clash’s “Complete Control”, Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer”, The Jam’s “In the City”, Magazine’s “Shot by Both Sides”, Siouxsie and the Banshees’ “Hong Kong Garden” (“a song written about a Chinese takeaway in suburban Kent”, in Nemone’s words).

No celebration of “alternative music” would be complete without the Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks” – “four teenagers from Derry . . . . Never mind The Troubles, here’s what teenagers really worried about” – or The Cure’s “10.15 Saturday Night” (“I’m sitting in the kitchen sink”?). The brutal “California Über Alles” by the Dead Kennedys, meanwhile, did nothing for Governor Jerry Brown’s chances of re-election.

It’s particularly pleasing to see the utterly original Wire get a selection with their song “Outdoor Miner”, from their sublime album Chairs Missing; all of one minute and 45 seconds long, it's hailed for its “sunny, nutty and fresh-faced optimism”; a song so beautiful and bizarre that its lyrics are worth quoting in full:

No blind spots in the leopard's eyes

Can only help to jeopardize

The lives of lambs, the shepherd cries

An outdoor life for a silverfish

Eternal dust less ticklish

Than the clean room, a house guest's wish

He lies on his side, is he trying to hide?

In fact it's the earth, which he's known since birth

Face worker, a serpentine miner

A roof falls, an under liner

Of leaf structure, the egg timer . . .

A cause for celebration is that a station that was almost closed down can now boast listening figures of 2 million plus – impressive given that it’s digital only. I for one have started listening to it only in the past year or so, and now alternate between Radios 3, 4 and 6 (how horribly smug and middle-class that must sound). I could happily spend most of Sundays listening to 6 Music, from Cerys Matthews’s laid-back show in the morning, via Iggy Pop’s excellent and educative two hours of consistently surprising choices, to Tom Robinson’s listener-led programme from 6 to 8 in the evening. Oh, Tom Robinson and his Band are in the Jukebox too: 1978’s “Up Against the Wall”, less well known than their hit “2-4-6-8 Motorway”, and almost as good.

October 27, 2014

Voices of the (un)dead

Photograph © Martin Parr/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Photograph © Martin Parr/MAGNUM PHOTOS

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

It’s clear that there’s an enduring taste for the dark side – in literature, theatre, film, television, music, art etc. All things Gothic, including Martin Parr’s photographs from Whitby Goth Weekend in April, as above, are celebrated in the new exhibition Terror and Wonder at the British Library, which was reviewed in last week’s TLS. This week’s issue (out on Friday) includes a review of classic horror stories, Mary Shelley as a bringer of life but also of death, and the fates of famous corpses, such as John Milton’s, whose body, apparently, was dug up by drunken opportunists and sold as lucrative keepsakes.

To accompany these unholy pieces, in the latest in the TLS’s series of readings Michael Caines, Lucy Dallas and I have chosen a trio of tales from the early twentieth century to personally mark the coming of Halloween. A very witching time of the year, when churchyards yawn and hell itself breathes out contagion to this world . . . – well, that’s how mysterious goings on are described in Hamlet, and The Winter’s Tale would also inspire the first of our short ghost stories – read and introduced by Michael – “There was a Man Dwelt by a Churchyard” by M. R. James, one of the undisputed masters of the genre . . .

My choice is an extract from “The Eyes” by the American writer Edith Wharton – a somewhat terrifying reminder that real horror is found in our imagination, often spurred on by a guilty conscience:

And later in the week, we’ll hear about a shape-shifting beast in the wood – Lucy Dallas’s selection is the short story “Gabriel-Ernest” by Saki, who, as Lucy tells us, is a writer not usually associated with ghost stories, but there’s plenty of black humour to make his tales suitably uncomfortable.

We hope you enjoy listening . . . .

You can subscribe to the TLS's free audio series via iTunes.

October 26, 2014

Hogarth in hiding

By MICHAEL CAINES

May 17, 1799: Samuel Taylor Coleridge reports back to his wife on his travels through Germany. He has passed through a village where Whitsun Tuesday was being celebrated with dancing around the maypole on the village green, leading him to remind her: "I am no judge of music". The musicians themselves, however, are another matter. "The fiddlers! - above all the bass-violer - most Hogarthian phizzes! God love them!"

William Hogarth had died some years earlier, in 1764, and the 250th anniversary of his death fell today; and today's political cartoonist could presumably draw just such a collection of "phizzes" if required, since the adjective "Hogarthian" has endured, I reckon, in precisely the sense Coleridge uses it.

As it happens, many TLS subscribers will have been reading this weekend (or online, here), about a sometime neighbour of Hogarth's, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds "dominated British art for some three decades" during the eighteenth century, as Norma Clarke writes in her review of Mark Hallett's Reynolds: Portraiture in action. For about a decade, these two British artists resided in Leicester Fields as uneasy neighbours: one of them in decline, the other on the up.

There's a good account of this period in Vic Gatrell's most recent book, The First Bohemians. In a nutshell: goodbye brilliant satirical series, Marriage à-la-mode and all that; hello, flattering depictions of the elite. Reynolds could keep on welcoming the bon ton into his studio because, as Norma Clarke points out, he could assure them something of the dignity or grace of an Old Master; by contrast, Hogarth could count among his last works the fiery "Enthusiasm Delineated" (1761), which, if Bernd Krysmanski is right, scorns the zeal for "sublime", traditional religious art. Having already parodied Dürer and Da Vinci, Hogarth had to revise this work, disguising its meaning entirely, as "Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism" (1762), a satire on Methodism that was deemed to be safer for public consumption:

Like "Francis Matthew Schutz in Bed" (which the vomiting sitter's descendants had censored, covering up his chamberpot with a newspaper), it's a reminder that, well beyond "Beer Street" and "Gin Lane", Hogarth's distinctive vision of the world hasn't always been appreciated. And that Hogarth himself was conscious of that, opting to keep hidden this, one of his most extreme statements of his views on art. He could adopt others' styles, as Reynolds could, but if that was all there was to it, "Hogarthian" would hardly have been Coleridge's word to describe the "phizzes" of German bass-viol players.

October 24, 2014

International (and parochial) Ibsen

Henrik Ibsen by Robert Bryden, 1899 (Wellcome Images)

By MICHAEL CAINES

It's the launch for the new Penguin Ibsen tonight, at the Barbican, where the "reimagined" Belvoir Sydney production of The Wild Duck has just opened. What does that tell us? Well, only that the stars were in an impish mood when they lined this one up . . .

The Barbican's International Ibsen season, which The Wild Duck brings to a close, has presented a trio of radical reworkings of Ibsen plays (the other two being An Enemy of the People and Peer Gynt) from abroad. The implicit contrast is with the tradition of Hedda Gabler and A Doll's House in crinolines, which endures in Britain at the expense of the kind of innovative, if not always successful, approach adopted when it comes to staging, say, Shakespeare.

As Andrew Dickson puts it, we seem to have a "harder time" here than elsewhere making Ibsen "talk our language". Dickson puts the blame on the "lingering effects of Stanislavskian realism" and "a Downton-like taste for period detail", and contrasts that with Thomas Ostermeier's brand of Ibsenism, which has provoked "walk-outs and outraged condemnation" but therefore seems true to the "divisiveness" that was part of Ibsen's point. I think that might be a large part of it, but, I hope, not the only reason. I don't think I've ever gone to the theatre in the hope of seeing some tasty period detail.

Whatever the answer, contrast that emergent experimental phase in the performance of Ibsen's plays (which some will have already seen in English venues such as the Birmingham Rep, the West Yorkshire Playhouse and the Young Vic) with the admirable aims of the new Penguin Ibsen project: to provide English readers with the best account yet of the original Dano-Norwegian Ibsen, with its complicated, shifting textures and nuances.

The basis for these new translations is the Henrik Ibsens Skrifter (the recently published, definitive edition of Ibsen's works). Its thoroughness in turning over every last verbal stone is certainly apparent in this Penguin volume of the four last plays – The Master Builder, Little Eyolf, John Gabriel Borkman and When We Dead Awaken. The notes draw attention to compound coinages ("Bergmand", literally "mountain man", idiomatically and in context "miner's son"), historical meanings, biblical allusions – with or without crinoline, of course, no modern production could hope to communicate all of this exactly and in full.

So we have the reading experience, on the one hand, striving to be iota-faithful; and on the other, the theatrical trend towards seemingly radical adaptation, with the old style of interpersonal relationships mapped onto the new, and the late nineteenth-century outcries of Nora Helmer et al updated for the era of the Occupy movement.

I'm happy to have both, and suppose tonight I'll find out if others feel the same. (Apparently, my almost total ignorance of Dano-Norwegian is no bar to my speaking at the event; strictly, I hope to discuss English productions of Ibsen and Ibsen in contrast to Shakespeare in the theatre . . . .) For now, though, I'll just note a further contrast:

As Toril Moi points out in her introduction to those four last plays, international Ibsen-mania is nothing new. The Master Builder appeared in Danish and "almost simultaneously", it was claimed at the time, in English, German and French, with Russian, Dutch, Hungarian, Czech and Polish to follow. Published in December 1892, it had its premiere in Berlin the following month, and Moi lists nine further productions by the end of May 1893 (including in London). Comparable demand surrounded the other plays.

I recently came across a later view of Ibsen, in Arnold Bennett's Journals, from August 1929:

"Only when you see the provincialism of Oslo do you appreciate the wonderfulness of Ibsen. It was as manager of the theatre at Bergen that Ibsen learnt for himself more about the stage than any other dramatist in nineteenth-century Europe. Now Oslo is a capital; it has three times the population of Bergen; it is much nearer the cosmopolitanism of Sweden. If Oslo is provincial – and you may even call it parochial – to-day, what must Bergen have been like in those early years when Ibsen, directing its theatre, formed his ideas and planned his schemes for the rejuvenation of the drama? Whence came the inspiration which enabled him to make all the plays of the continent seem petty, parochial, and ingenuous in comparison with his own? This is a mystery which cannot be explained, and certainly Ibsen himself could not explain it. I doubt whether any creative artist ever can satisfactorily explain his causation.

(A reminder that the international Ibsen was also the parochial Ibsen – in the same way, perhaps, that that other international phenomenon Shakespeare was also Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon.)

"I remember the time when Clement Scott in the Daily Telegraph used to attack Ibsen violently, to shoot him to pieces with epithets. (Ibsen never seemed to notice that he had been shot to pieces by the most influential dramatic critic in the biggest city in the world.) The mildest of the charges brought by the angered Scott against Ibsen was that he was parochial. In those days, thirty or forty years ago, I was indignantly anti-Scott. Ibsen parochial! The notion was grotesque. But to-day I do have a glimmering of what Scott was driving at. In a way Ibsen is parochial. (So were Aeschylus and Thucydides.) It was like Ibsen's immense cheek to assume that the élite of Europe could be interested in the back-chat and the municipal and connubial goings-on in a twopenny town of a sort that nobody had ever heard of. Ibsen's assumption nevertheless proved to be correct.

Yes. Ibsen was parochial, even in his finest plays of contemporary life; but he lifted parochialism to the mundane and the universal. Read or see Ibsen's social dramas without prejudice, and the still small voice within you will say: 'But I know that town and its inhabitants. I have lived in it, and among them. I am living in it.' Fundamentally, we are all living in Bergen."

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers