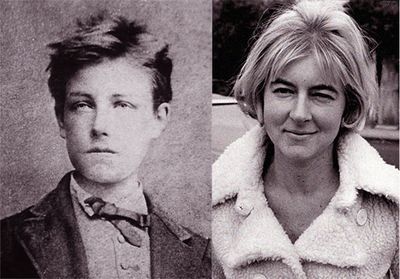

Did Rimbaud and Tonks really ‘disappear’?

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Rosemary Tonks in 1969; Photo: Associated Newspapers/Rex Features

Poets can be business-minded and highly sociable. They can live long lives. Many people will deny it, but that’s nothing new. At Wednesday night’s Poet in the City event at King’s Place, N1, a gathering – which included Tim Matthews, Professor of French and Comparative Criticism at UCL, the poets Matthew Caley and George Szirtes, and Neil Astley, Editor of Bloodaxe Books – took as its premiss the “strange disappearance” of Arthur Rimbaud in 1879 and, a hundred years later, that of the British poet and novelist Rosemary Tonks. Both were descendants, more or less directly, of Charles Baudelaire, chronicling their urban spleen; then, they “vanished”. This was, our hosts told us, a “great literary whodunit” . . . .

Except that the perpetrators were not only known from the outset, they were known by the poets themselves. It was, in fact, the poets whodunit: for Rimbaud, to renounce poetry in favour of trading coffee, arms – and some think, slaves – in the Horn of Africa, was, as Paul Verlaine later put it in Les poètes maudits (1884), “logical, honest, necessary”. Rimbaud had said as much himself in the mid-1870s, when, squatting in London, he wrote “Départ”: “Assez vu…/ Assez eu…/ Assez connu….”.

Tonks, too, had signed a confession years before swapping London for Bournemouth, in her poem “The Sofas, Fogs and Cinemas”: “All this sitting about in cafes to calm down / Simply wears me out . . . . / I have lived it and I know too much”; she was, she said, “psychologically smashed”. (This frazzledness was conveyed on the night by the actress Lucy Tregear, whose readings of Tonks, in the style of Emma Thompson directed by Richard Curtis, clearly channelled the Bodley Head’s assessment of Tonks’s novel The Bloater (1968) as “the more than half-serious dilemma of whom to choose as a lover”.)

A whiff of mystery, literary exile or, as Verlaine had it, damnedness, can, of course, help to generate interest – Tonks’s Collected Poems, published by Bloodaxe, was launched last night and will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS – but it can also obscure the granular detail of a life lived, in the case of both poets, to the full.

Both Rimbaud and Tonks wrote every day – lists and diary entries for the most part (“more Beckett than Byron”, said Matthew Caley), and, in Rimbaud’s case, there are letters a-plenty – just not ones addressed to the literary establishment. Astley, who wrote Tonks’s obituary for the Guardian earlier this year, had her living by the sea as “the reclusive Mrs Lightband”. (One could be forgiven for thinking it a pseudonym adopted after her rebirth in the 1970s as a fundamentalist Christian; it was in fact her marital name, kept in spite of divorce.) He had repeatedly attempted a correspondence with the poet, hoping to persuade her to reissue her poetry; only after Tonks’s death, when he read her assiduously written diary, did he learn that, on receiving a card from him in 2009 (alerting her to BBC Radio 4’s feature on her, “The Poet Who Vanished”), she had noted in her diary: “Second postcard from Satan.” What would she think now?

Astley revised his portrait following the discovery that Tonks was, in fact, pretty active up until the last, enthusiastically handing out Bibles and travelling to London to step up to the box at Speakers’ Corner. (An updated version of his Guardian piece appears in the Bloodaxe edition.)

As for Rimbaud, Szirtes’s explanation that the poet had “peaked . . . had covered all the opportunities available to him” is arguable, to say the least. Tonks perhaps came closer to the truth when, writing on Colette in the NYRB in 1974 (her last published piece), she said that Colette couldn’t write straightforward novels because they “might very likely have seemed to her not truthful enough to what was all around her”. Both Tonks and Rimbaud would have been aware that “There is the danger, in finding one’s ultimate reach in literature, of losing the original talent with which one set out” (Tonks on Colette again).

As for the common desire to see poets as hovering precariously on the brink of disappearance – be it a social, financial or physical wasting away – perhaps it all comes down to Caley’s comment towards the end of the night’s proceedings that “most modern poets would love to be noticed if they disappeared”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers