Peter Stothard's Blog, page 34

December 9, 2014

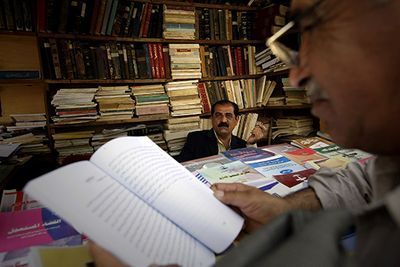

Al-Mutanabbi Street starts here

A bookshop in Al-Mutanabbi Street; JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images

By DAVID COLLARD

At the annual Small Publishers Fair recently (blogged about by Michael Caines here), I fell into conversation with a friendly stallholder who gave me a bookmark carrying the cryptic message “Al-Mutannabi Street starts here”. That was all. She politely but firmly refused to answer any questions about it but the street name rang a very faint bell. Intrigued, I went online to find out more. There was plenty to discover and I’ve since been catching up on an extraordinarily moving and impressive literary project.

On Monday March 5, 2007, at the height of the sectarian war in Iraq, a car bomb exploded on Al-Mutanabbi Street in Baghdad, killing more than thirty people, wounding more than 100 and destroying many small businesses, including a host of small bookshops and bookstalls. No group has claimed responsibility for this devastating attack. The street, named after the tenth-century classical Iraqi poet, was the equivalent of London’s Charing Cross Road in its heyday, and the heart of Bagdhad’s intellectual and literary community.

Reading about this event, Beau Beausoleil, a poet and bookseller based in San Fransisco, felt that a gesture of solidarity was called for and set up “The Al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition”, which has since been working to establish and maintain a link with the people of Al-Mutanabbi Street. In 2007, Beausoleil’s “Call to Action for Letterpress Printers – Al-Mutanabbi Street Broadsides” brought writers, poets and artists together to produce a series of broadsides printed on traditional letterpresses. The project has since expanded into other media, including 260 one-off books designed by artists supporting the cause, and an anthology of writing published as Al-Mutannabi Street Starts Here, co-edited by Beausoleil and Deema Shehabi (PM Press, 2012).

In 2013, printmakers around the world were invited to make prints for the project and to become part of a global coalition committed to the belief that “wherever people talk freely and creativity breathes, Al-Mutanabbi Street starts”. Each printmaker has donated five prints from their edition to the project. One complete set of prints will be donated to the Iraq National Library in Baghdad and the other copies will be on show in touring exhibitions around the United States, Britain, the Middle east and North Africa. The inaugural show will open at the San Francisco Center for the Book this Friday.

Earlier this year a selection of the prints was displayed in London’s Mosaic Gallery. More than fifty British artists are among the hundreds involved in the endeavour. If you’re reading this, you might wish to spread the word. Al-Mutanabbi Street starts here.

December 5, 2014

In praise of ugly cities: Le Havre

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Le Havre, France’s second largest port after Marseille, was 85 per cent destroyed by Allied bombs during the war. Five thousand civilians lost their lives. Arthur “Bomber” Harris was apparently later to regret that the destruction had done little to hamper the German war effort.

The architect Auguste Perret was commissioned to rebuild much of the centre of the town in the early 1950s, including the church of Saint Joseph (below), which is also a memorial to those killed in the raids. Built on an octagonal base out of reinforced concrete that appears to change from grey to beige depending on the light, it dominates the skyline with its 107-metre tower, and looks frankly indestructible.

During a recent visit to the city, principally to see the Nicolas de Staël exhibition, I was struck by the weird concrete beauty of the centre. Unesco declared the city centre a “world heritage site” in 2005 for its “innovative utilisation of concrete’s potential”, citing it as "an exceptional example of architecture and town planning of the post-war era". (It’s a shame, however, that Oscar Niemeyer’s House of Culture appears to be undergoing extensive refurbishment.)

Another innovation is the placing of literary benches around the city – twenty in total. These mark the spot where a scene in fiction can be identified as having taken place, from Flaubert, via Stendhal, Sartre, Céline, Henry Miller (Tropic of Cancer) and Simone de Beauvoir to less well-known present-day writers. It’s a clever imaginative idea and sets the visitor to the town on a pilgrimage of sorts.

In the centre is the public garden where Antoine Roquentin, the narrator of Sartre’s first novel La Nausée (1938, Nausea), has a kind of epiphany. And there’s the bench to mark it. The novel is set in a fictionalized Le Havre, which Sartre calls Bouville. (The writer taught at a lycée in Le Havre in the 1930s.)

Roquentin is doing some research on an eighteenth-century figure, M. de Rollebon, in the town’s historical archives and library – where he occasionally encounters a hapless autodidact who's reading his way through French literature alphabetically (I’d forgotten how violently their acquaintance ends). The town’s bars and cafés are dimly lit but comforting, its streets rainswept. He regularly visits the Rendez-vous des Cheminots, where he’s carrying on a desultory affair with the patronne.

At one point Roquentin describes a Sunday scene:

“The brothels are opening for their first clients, men from the country and soldiers. In the candlelit churches, a man is drinking wine in front of women on their knees. In all the suburbs, between the endless factory walls, long black lines of people are on the move, advancing slowly towards the centre of town.” (my translation)

“[U]n homme boit du vin devant des femmes à genoux” is very Sartrean, speaking volumes about his view of organized religion.

Later he writes “I’m going to read [Balzac’s] Eugénie Grandet. Not that I take any great pleasure in it. But I have to do something”.

Roquentin clearly didn’t fall in love with Le Havre. Neither, presumably, did Sartre. I have to say I really liked the place.

December 3, 2014

A is for . . .

By TOBY LICHTIG

Plumbing the depths of literary triviality recently, I found myself wondering about single-letter book titles. This autumn I reviewed J by Howard Jacobson and F by Daniel Kehlmann, both dystopian in their own way, both truncated titles standing for a sense of malign mystery, denial, nullification. The “J” of Jacobson’s title is a substitute for the unmentionable word “Jew” – Jews, in the nasty new world portrayed by Jacobson, having been (superficially, temporarily) “erased” from Britain. The “F” of Kehlmann’s book is the title of a mysterious novel within the novel, which explores the negation of the self. It causes such anguish in its readers that it brings about a spate of suicides.

Also in this elusive category is G by John Berger (the letter stands for its protagonist, Giovanni) and V by Thomas Pynchon (“V” is both a MacGuffin and the geometric intersection of the book’s two narrative strands). I've always been intrigued by Q, but perhaps this is mostly for the enigmatic Italian collective known as Luther Blissett (named after the 1980s footballer of Watford and A. C. Milan who once declared, of his time in Italy, that “No matter how much money you have here you can't seem to get Rice Krispies”). Another collective (including Jean Echenoz) produced the novel S in 1991, and that same title was used by J. J. Abrams earlier this year. Abrams’s S, like Berger’s G, is named after its protagonist, the vagueness of whose name is a symbol for his amnesia; so too is Tom McCarthy’s C, a nod to, among other things, its anti-hero Serge Carrefax. W by Georges Perec is similarly about uncertainty, silences, unreliable memories: Perec was himself a master of omission, in his Oulipian guise.

A quick internet search turns up several other single-letter titles: e by Matt Beaumont, described as “a tapestry of insincerity, backstabbing and bare-arsed bitchiness”; its upper-cased namesake E – an “incredible” history of ecstasy by Douglas Rushkoff; O by Jonathan Margolis, an “intimate” history of the orgasm; and Y, Steven Jones’s biological study of maleness.

But here I’m more interested in literary novels. I was surprised that no-one appears to have published a novel entitled X, and was then heartened to see one forthcoming (in early 2015) by Ilyasah Shabazz, none other than the daughter of Malcolm X. And where on earth is A, which would finally supplant D. H. Lawrences’s Aaron’s Rod at the beginning of literary encylopedias? Surely someone’s missing a trick here.

Do these enigmatic titles conjure anything particular in their single letteredness? Is there something deeper they have in common? Is there a thesis to be written about them as a whole? Almost certainly not. And yet, I can’t help wondering . . .

December 1, 2014

Love letters

By DAVID COLLARD

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural.

Louis MacNeice’s lines come to mind in any consideration of objectophilia – also known by the German term Objektophilie (OS) – a profoundly strange sexual orientation expressed through an intense physical and emotional relationship with inanimate objects. Media coverage tends to adopt a chortling and prurient tone when reporting cases such as that of a thirty-seven-year-old former soldier named Erika LaBrie, who went through a “commitment ceremony” in 2008, taking as her partner a major Paris landmark and changing her name to Erika La Tour Eiffel. She pictured her spouse as female: “What we have is real and if it's only real to me and it's only real to her then that's fine”.

The objects of OS affection are jaw-droppingly bizarre – an electronic keyboard, the Twin Towers, a length of fencing, a guillotine, a particular bridge, buttons, a roller-coaster, a ferris wheel, a family saloon car. Nothing, it seems, is off-limits. Of particular interest to those of us with a literary bent is the case of Eva K., a woman from the Netherlands who has an intense relationship with words that exceeds any run-of-the-mill logophilia. Writing on an OS website in 2011 she said: “To fall in love with a word, a logo or a name has always been something entirely normal to me. As a young girl I already felt an exceptional, inflationary attraction to the spoken, and most of all to the written word, which no other person around me seemed to understand.”

Much more than a mere liking for a particular word or phrase, hers is a passionate and compensating obsession. She cannot imagine romantic relations with a human being and has never, she says, felt any attraction to others, in this respect seeing herself as an androgynous, asexual being.

Her emotional investment in words is complex and sophisticated, involving what she describes as “the most delicate fine tuning which is comparable to experiencing music or art”. She adds: “During my life there must have been over 50 very special words and names I was madly . . . passionately in love with. I have documented them all . . . Being in love with a word means: All the things one would experience when in love with a person; all emotions associated with adoring feelings of love, romance and erotic sensitivity.

Eva consummates her desire “through the making of graphic creations. I usually design my own artworks with the words, sentences, or names I love”. She is “powerfully attracted” to Russian, Polish, and Latin and, although no linguist, has an affectionate regard for grammar rules and particular lexical items, declinations and conjugations: “It is about specific combinations of letters. The kind of typeface plays a big additional part. In general I do not like words written entirely in CAPITALS, but prefer Capital + lowercases. There are a few typefaces I really love in which my words appear in the most attractive way. In my letter-object-artworks this is the typeface I habitually use.”

OS has been linked to psychological conditions including Asperger Syndrome, sexual trauma, gender dysphoria and synaesthesia. It seems to me that objectophiles in general, and Eva K. in particular, present, in an extreme form, a tendency to be found in many creative artists and writers. There are writers whose fictions – if only in the mildest way – seem to me to take an objectophile perspective on the world. There is Nicholson Baker, for example, with his intense scrutiny of library systems; J. G. Ballard, with his concrete flyovers and eroticized automobiles; William Burroughs. And that’s just the Bs.

In myth Endymion aimed high and fell for the moon (and why OS isn’t known as an Endymion complex is a matter to ponder) and there is no end of erotic objectification in literature – Volpone’s feeling for gold goes beyond the merely miserly.

It’s impossible to make sweeping statements about such a complex condition although research suggests that many objectophiles are female and cheerfully polygamous. Eva K. continues: “My deepest emotions have always been shared with written words, names, and languages. However in the past I have had romantic attractions to public objects from here in the Netherlands and also outside of the Netherlands. Among them was a world-renowned hydraulic flood barrier in Holland who was my love for six years as well as a wonderful floating crane and a few other public buildings that I have shared an objectum-sexual love.”

A scholarly account of the condition is “Love Among the Objectum Sexuals” by Amy Marsh, DHS, ACS, available online in the Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality (Volume 13, March 1, 2010).

Eva K. concludes: “Words, names, and languages always were my greatest and most passionate loves . . . and will probably remain so as long as I live”.

November 28, 2014

Putting things in order at the British Library

By DAVID HORSPOOL

Sometimes, dating things can be a bit of a distraction for historians, though putting things in the right order might seem like the least we should expect of them. Yesterday, at the British Library’s announcement of their exhibitions and events for 2015, dates were much discussed. There were anniversaries: 800 years since Magna Carta, 150 since the publication of Alice in Wonderland, 200 since the birth of Anthony Trollope.

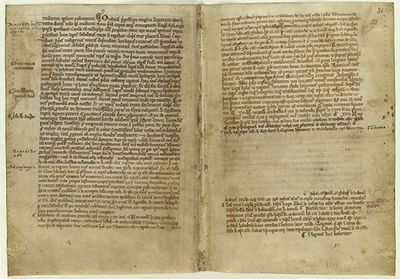

But there was also the question of putting things in order. For the Library’s Magna Carta exhibition, “Law, Liberty, Legacy”, which will run from March 13 to the beginning of September next year, one of the most intriguing exhibits will be the Library’s manuscript of the Scottish Melrose Chronicle, Cotton MS Faustina B IX (pictured above), which contains what is described as “the earliest independent account of the negotiations between King John and the Barons at Runnymede”.

While the revelation of this may be exaggerated (the modern printed edition of the Chronicle of Melrose was published in the 1930s, for example), it is arguable that historians have been looking the wrong way, seduced by the help that the Scottish account can give in ordering the confused events of June and July 1215, when a group of English barons and senior churchmen tried to tie King John to some formal obligations, and John did his best to wriggle out from under them. So in J. C. Holt’s classic account of Magna Carta, Melrose is introduced mainly to provide evidence of whether what we know as Magna Carta was sealed at Runnymede in June, or in Oxford in July (and in fact, the chronicler doesn’t mention Runnymede). Holt describes Melrose as a “somewhat confused narrative”but uses it to help him confirm that Runnymede is where the document was sealed, and Oxford where John repudiated it.

But the remarkable fact that the impact of the events of 1215 had, so soon after they happened, spread as far as Melrose, and that the monk who recorded them was moved to do so in Latin verse, is passed over without comment. It used to be a truism of Magna Carta historiography that the Charter at the time was a narrow self-serving document that made little impact. That is the tenor of another exhibit, a letter written from the Colonial Office in 1947 refusing to endorse a “Magna Carta Day” in the Commonwealth, not only because it might give “ill-disposed colonial politicians” the wrong idea, but because Magna Carta itself is deemed to have little to do with wider questions of rights and responsibilities. The Melrose Chronicle, with its description of the barons’ attempt to get the King to “make a thorough reform of the laws”, creating “a new state of things in England . . . for the body wishes to rule the head, and the people desired to be masters over the king”, shows that soon after Magna Carta was drawn up, its wider implications were already hitting home.

Dating crops up again in the case of a collection of early letters of Harold Pinter (pictured below), the acquisition of which was also announced yesterday. There are about 100 of them, written to childhood friends (Mick Goldstein and Henry Woolf) when Pinter was between eighteen and thirty. Many have no dates. But the Library was able to pin down about a third of them by making use of Pinter’s constant cricket references. So, for example, in a letter to Goldstein of 1955, discussing Beckett,and insisting that his friend sees “En Attendant Godot” at “the Arts in London (“Are you going to do this?”; Pinter had not himself seen the play), it is the reference to “Padgett” (“you brought his stroke to me, and lo, didn’t he get a century yesterday, to bear out your words”) that helps the curators to say that the letter “must have been August 1955”.

Actually, this merits further investigation, or perhaps explanation, as Doug Padgett only scored one first class century in 1955, for Yorkshire against Warwickshire at Edgbaston, where on the first day he was bowled for 115. That was July 23, which, if it was Pinter’s “yesterday”, may mean the letter was written on July 24. But I could be wrong, and though dates do matter, it is perhaps more important to note that the young Pinter was clearly enthralled by Beckett, even if he was yet to see Godot.

It is also interesting that Pinter writes about “Betty”, described by a third party as “secretary to some Irish writer she’s been translating his work from French back into English [sic]”. Pinter says he met Betty, but doesn’t give her last name. Pinterians and Beckettians probably know all about her, but I was intrigued to learn of this woman who apparently translated Godot and Molloy back into English, a task I had always thought Beckett completed on his own. Pinter writes that Betty “spoke a lot of ‘En Attendant Godot’ and is going to send me a copy, I hope. In French, though. Once again all I got was that two tramps sat and talked, waiting . . .”.

November 27, 2014

Young Skins and the old prize-watching habit

By MICHAEL CAINES

In general, I'm not a fan of the annual literary shortlists and prize hype, being hopelessly biased as I am in favour of readers taking guidance, should they need it, from book reviews rather than "Shortlisted for" stickers, and preferring to pose as an individualistic grouch rather than a group reader.

But I have had to admit to myself that this suspicious attitude doesn't stop me rooting for the (very) odd friend who's shortlisted for something or taking a gossipy interest should I happen to meet a prize judge or hear a good story about the hype, the manoeuvring for position etc (like the fine anecdote the wife of a Man Booker judge told me about the arrogant novelist who dramatically transformed into a kowtowing creep the moment he worked out "who she was").

And much as I loathe the idea, I'll certainly take note yet again of the difference an award can make the next time I go into Foyles on Charing Cross Road: after a certain announcement was made last night, at an altitude nearer the top than the bottom of London's heavily scaffolded Centre Point, I went to the bookshop just out of curiosity, to see if the winning book was there . . .

And so it was, just about – there were two copies tucked away in a corner, on the bottom alphabetized shelf. Something tells me that by now it will have been given a more prominent position at the front of the shop.

Yes, the Guardian did a good thing last night and gave its First Book Award (the TLS classics editor Mary Beard is one of this year's judges; reading groups are also involved in the judging process) to the young Irish writer Colin Barrett for his short story collection Young Skins. Barely a few hours off the plane, he stood up, took the applause and his award, and heard himself described as a writer "who can go the distance" – ie, this wasn't just a reward for what he has written but what he threatens to write in the future.

By my reckoning, this is the third time a short story collection has won the prize, which replaced the venerable Guardian Fiction Award in 1999, following An Elegy for Easterly by Petina Gappah in 2009 and A Thousand Years of Good Prayers by Yiyun Li in 2006. That's an impressive record for a genre that we're intermittently told is under threat of critical neglect or even, wildly, of complete extinction – especially given that this particular prize is open to all genres, not just fiction long or short.

What I've read of it struck me as superb for the same reasons it's been acclaimed elsewhere. Back in the spring, in his TLS review, Matthew Wolfson described Barrett's stories, set in a fictionalized western backwater town called Glanbeigh, as "raw testaments to the socio-economic wreckage of impoverished rural Ireland". Ordinary life is "infused with violence"; in this world, you could call "The boot to the face", in "Stand Your Skin", ordinary. And in this week's TLS, as it happens, Helen Simpson has chosen Young Skins as one of her Books of the Year (her selection is behind the TLS paywall, but there is also this freely available selection from Eimear McBride, Andrew Motion and others). Who could more authoritatively say than Helen Simpson that a short story collection is "outstanding"?

Like Yiyun Li's collection, Young Skins has already won this year's Frank O'Connor international short award, whose judges oxymoronically described it as an "instant classic"; does all this acclaim mean that we have here a case of that strange and marvellous phenomenon known as a Critical Consensus? Well, maybe – I've yet to find an outright bad review of Colin Barrett's book, just some marginally less enthusiastic comments – but the boost of winning a prize usually means that the lucky prizewinner stands a better chance of ending up in the hands of somebody who absolutely hates it. I came across the recommendation online that Young Skins would make a good Christmas present. For the fan of brutal Irish youth in your life, maybe. I'm looking forward to reading to the extended (and infuriated) Amazon reviews condemning it (seasonably) as an "instant turkey".

November 26, 2014

What’s so special about Shakespeare’s First Folio?

Photos by DENIS CHARLET/AFP/Getty Images

By MICHAEL CAINES

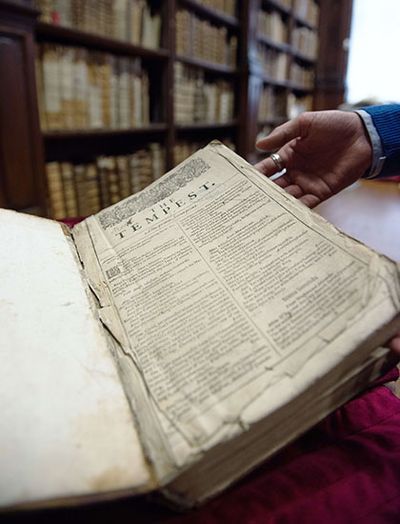

Welcome news from Saint-Omer in the Pas-de-Calais: a copy of Shakespeare's First Folio has been discovered lying unacknowledged in the collections of the Bibliothèque d'agglomération de Saint-Omer, after it was mistakenly catalogued as an eighteenth-century book.

The excitement of the librarian who made the discovery, Rémy Cordonnier, is understandable, and one of the chief experts in the field, Professor Eric Rasmussen, has authenticated the copy and called it "magnificent" – a rare accolade for such a discovery. And Professor Rasmussen, as the author of The Shakespeare Thefts: In search of the First Folios and the co-editor of The Shakespeare First Folios: A descriptive catalogue, ought to know. "First folios don't turn up very often", he has said, "and when they do, it's usually a really chewed-up, uninteresting copy."

The newspapers have duly reached for the estimated price such a book might go for at auction – £4 million, maybe – and the Independent has described the First Folio as being like the "Holy Grail for Shakespearean scholars".

My only qualm is that's potentially a misleading way of putting it. . . .

The Holy Grail is meant to be a unique artefact (let me know when you find it). Individual copies of the First Folio can be, too, for different reasons (but we've already found lots of them). From every existing copy there is meant to be something to be learnt – from annotations, stop-press changes and the like. The Saint-Omer copy has a name written on it in a contemporary hand, that may speak of "Shakespeare's place in Catholic culture", and there are apparently "notes and directions on the play Henry IV", including a change of gender in the Eastcheap tavern, from "hostess" to "host" and "wench" to "fellow", possibly with the practicalities of casting in mind.

By the standards of seventeenth-century drama, I suspect that First Folios are actually more glamorous than genuinely rare. Of something in the region of 800 copies that the experts say were printed in 1623, the Saint-Omer brings the number of survivors up to 233 (about seventy of which have emerged over the century since Sir Sidney Lee's census of 160 copies). That makes it less of rarity than another of Saint-Omer's major treasures, a Gutenberg Bible, which maybe had a print run of only 180 copies, not to mention the library's collection of manuscripts and incunabula.

For those (relatively few?) Shakespeare scholars who need to consult in person a good number of Folios, and can apply for grants and fellowships, the Folger Shakespeare Library has eighty-two copies (while the rest of us have the option of consulting the digitized copies held in New South Wales and Brandeis University, the Bodleian in Oxford; Saint Omer's copy is also to be digitized). Another twelve are at Meisei in Japan; only six of the survivors are still in private hands.

Compare that with the opposite extreme, represented by the Lost Plays Database set up a few years ago. Here's what kept Tudor and Stuart England entertained besides Shakespeare between 1570 and 1642, and of which we know sometimes only a title and a few tantalizing details. "A Bad Beginning Makes a Good Ending" was probably a comedy performed at Shakespeare's company, the King's Men, at Court in the "winter holiday season" of 1612–13. Another company, the Earl of Worcester's Men, may have had another Osric ("Marshall Osric" by Thomas Heywood and Wentworth Smith), around the time of Shakespeare's Hamlet. And wouldn't it be just a little bit interesting to have a snippet of "Strange News Out of Poland", "The Siege of London" or "The Stately Tragedy of the Great Cham"?

And then there are the plays that exist in only a single known copy, such as surviving fragment of the Henry IV part 1 quarto of 1598, or the first quarto of King Lear, of which there are a dozen copies (or at least there were, in W. W. Greg's day).

In other words: Shakespeare First Folios are not the rarest of all rarities, wonderful though the news of another one is. It's just rare to find another one now – 2006 was the last time a complete copy sold at auction, I think. See Emma Smith's review of The Shakespeare Thefts and The Shakespeare First Folios in 2012 ("Take a thief") for the long view of the matter.

Many more plays of the same period, as Lois Potter has pointed out in the TLS ("Theatre before Shakespeare"), were simply never printed – or emerged under different titles, making it difficult to keep track of them, or even impossible to recover anything more about them than the kind of scraps given above. It's probably a safe bet that few of these apparently ephemeral entertainments and masques, as well as comedies, histories and tragedies, were lost masterpieces on a par with King Lear. But all the same, out of selfish curiosity if nothing else, I wouldn't mind having a few of them back – maybe even instead of (as if such a thing were possible) a 234th First Folio. Sheer blasphemy, I know . . . .

November 25, 2014

Sir Gawain in tight jeans

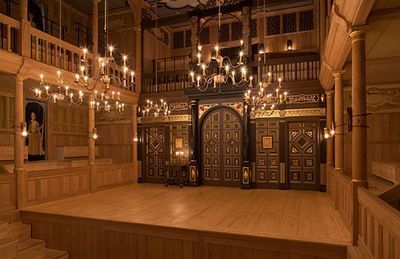

The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse; © Peter Le May

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Nothing says Christmas like bright berries of blood flecked across an emerald gown. This rather festive image comes by way of Simon Armitage’s translation, published in 2008, of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which the poet performed by candle light last night in the Sam Wanamaker indoor theatre at the Globe.

I say performed because, though Armitage read from his book poised on a lectern, he was joined by two actors, the gamine Polly Frame, reading the parts of the knight (in a gruff Scottish accent) and his lady (with soft BBC English ), and a foppishly blond Tom Stuart taking the role of Gawain (from the Home Counties?). Much fun was made of the chasm between role and player, Frame’s “bushy green brows” and “bushy green beard” being nowhere in evidence – and, at a meta-level, with Gawain, a would-be valiant knight whose nervous inexperience was captured in Stuart’s occasional quiver of falsetto.

Simon Armitage; © Helena Miscioscia

The actors, too, read their lines from books held aloft, which hampered their movements about the stage somewhat and once or twice obscured their face – which seems an especial shame in such an intimate venue. This small quibble was almost made up for by the theatricality of Armitage’s shirt – silk, I think, and of a bright emerald hue (sadly, no images are available so this too might pass into myth).

I had not yet been to the Wanamaker and was quite taken aback by its magic: the famous chandeliers; the intricacies of the panelled paintwork; the smell of wood sap, the harp player (Jon Banks) upstage right, strumming time and the passing of the seasons (with the occasional comic interjection); and the venue’s small size, which encourages the kind of personal exchanges between players and audience that would get lost in a larger venue. When, for example, from the poem’s opening, Armitage said, “Now, on the subject of supper I’ll say no more / as it’s obvious to everyone that no one went without” – then looked up, an eyebrow slightly raised – I’d wager that much of the laughter came from a common knowledge that we had all gone without to get there on time.

The tongue-teasers and verbal gymnastics required of the readers – the alliterations and bob-and-wheel patterning of the Middle English text are preserved in Armitage’s translation – made for more merriment. I recall, in particular, the lines recounting an exchange between the mysterious lord, just back from a successful hunt, and his guest Gawain: “And Gawain is quick to compliment the conquest, / praising it as proof of the lord’s prowess, / for such prime pieces of pork / and such sides of swine were a sight to behold”. There is a heightened sense here of a young man hysterically out of his depth. The lines executed, Stuart could look up and wink at his audience. It was all gloriously camp.

But what came across perhaps even stronger was the sense of a text – and a tradition – still very much alive, its contexts and references easily mutating for a modern audience: the line on “the wilds of the Wirral”, for example, “whose wayward people / both God and good men have quite given up on”, a comment of WAG culture; Gawain’s fashionable skinny jeans and flimsy brogues; when Gawain expressed his urgent desire to “link up with [the green knight]”, he might well have said “Link In ®”. Which got me thinking about another evergreen inflection: isn’t there a part of the knight that seems particularly aggrieved by Gawain's being who he is purely because of his relation to Arthur? And indeed, wasn’t it because Gawain was aware of what many in his uncle’s Court must have thought of him – “I am the weakest of your warriors and the feeblest of wit . . . .Were I not your nephew my life would mean nothing” – that he stepped up to the challenge – “I stake my claim, this moment must be mine” – and set heads rolling in the first place?

It was good to see the night’s tale brought to a close by the poet taking a bow with his players. There is something very modern about Armitage’s celebrity (going on book tours; fronting BBC programmes; singing in a rock band), which leaps the chasm to land neatly in line with the bardic tradition.

November 24, 2014

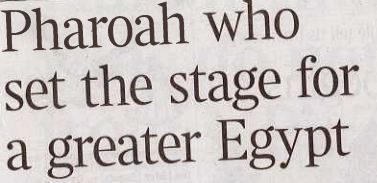

On ‘pharoah’ watch

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Did you spot the typo in the heading above? Did you have to look twice or did it leap out at you as it did at me? But then I have to confess I’m on permanent, obsessive “pharoah” watch; if I had a pound for every time I spotted one in the papers . . .

The rather interesting article, published last Saturday, was about Senusret III, who reigned c.1872–1854 BC. The article itself contains two “pharoahs” and the exhibition information at the end refers to “A Legendary Pharoah”.

Having seen ""pharoah" so many times, I decided to check whether the spelling was an acceptable variant – it appears not to be, so it’s just a plain error. Other common errors include “elegaic” (try saying it) and, less frequently these days (presumably because of spellcheck), “dessicated”, “abbatoir” and “mocassin”. Oh, and “momento mori” – the assumption presumably being that the first word shares a root with “moment”.

So it’s mostly a case of transposed vowels (easily done) or doubling the wrong consonant (ditto). I guess the eye takes in the word as a whole rather than letter by letter, hence the ease with which typos get through.

I’m as guilty as anyone on this count. As a page-reader at the TLS, I’ve (I’m sure more than once) let “principal” through for “principle” and vice versa. And I wrote a blog last year in which I referred to a harbour “peer” rather than pier.

But it’s always fun to see typos in a heading, or simply unfinished headings: “Vern, I need a heading here” once appeared in the Independent, I think. And captions can be a minefield too: the Guardian some years ago published a photo-montage captioned “Binch of crappy travel mags”. Their wonderful “Corrections and clarifications” column pointed out the next day that that should have read “bunch of crappy travel mags . . .”.

November 23, 2014

The Aldine Press, 500 years on

By CATHARINE MORRIS

If you’re familiar with the concept of the “biblio-binge”, as Michael put it in his most recent post, there’s a good chance you’ll enjoy a small exhibition at the British Library, of books printed by the Aldine Press, founded in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1494 and run by him and by two further generations of his family – all distinguished scholars and teachers as well as printers – until 1597. (The exhibition, which was curated by Stephen Parkin and will run until January 25, marks the 500th anniversary of Aldus’s death.) The press was extremely influential in terms of design, and produced some exquisitely beautiful volumes, easily recognizable from their dolphin-and-anchor emblems and sought after by collectors.

We encounter, for example, Constantine Lascaris’s Erotemata, 1495, a popular Greek grammar and the first book Aldus printed, for which he brought in expert help to meet the considerable challenge of rendering Greek script. Then there is Hypnerotomachia poliphili (1499; see picture below), an esoteric love story in Italian attributed to the Dominican monk Francesco Colonna, which is accompanied by sophisticated (though, like the text, anonymous) woodcuts. It became Aldus’s best-known volume.

There is a first edition of the Italian letters of St Catherine of Siena, 1500, which contains the first ever use of an italic font – it was designed to mimic scholars’ handwriting, we are told, and to make the text more readable – and a 1501 edition of Virgil which exemplifies another innovation: the octavo format, which enabled readers to carry the books around with them and therefore embodied “the renaissance belief that antiquity provided models to be imitated in all activities”. Petrarch is represented in an edition (1501) of Le cose volgari; the scholar-poet Pietro Bembo edited the text using a manuscript in his own possession. Late in life Aldus wrote a Greek grammar himself, which was published posthumously; the pages on display present forms of the verbs "to dig" and "to sow" in elegant tree diagrams.

After Aldus’s death the press was run by Aldus’s father-in-law Andrea Torresani, and Torresani’s sons (who for legal purposes, we are told, were regarded as Aldus's nephews). When Andrea died there was “a bitter quarrel over the inheritance”, we learn, but Aldus's son Paolo Manuzio reopened the press in 1533, and Cicero’s Epistolae familiares, published that year – its long, thin octavo format providing space for annotations below the text – marks a return to form. Thirty years later, Manuzio was head of the first Vatican printing press, and the exhibition also includes the Council of Trent’s Canones et decreta, 1564. The significance of the blue paper on which it is printed is unknown, but “it appears to have been another Aldine invention”.

The first scholarly work of Aldo the Younger (Paolo’s son) had been published in 1556, when he was nine years old. “Burdened by the legacy of his family”, we read beneath a little copy of his Phrases Linguae Latinae, an English edition published in London in 1581, “he tried, with various degrees of success, to make a career for himself as a scholar unconnected to the printing trade”. He is often overlooked, the exhibition explains, but he was well known in Europe, and this edition was reprinted many times.

A first edition of Torquato Tasso (1581) – with changes marked on it in Aldo the Younger’s hand (identified by Sir Anthony Panizzi, Principal Librarian of the British Museum 1856–66) – demonstrates the calibre of the writers the Aldine Press attracted, even in the last quarter of the sixteenth century when "the quality of its output was . . . in decline".

The exhibition makes clear that the Aldine Press also attracted eminent collectors. Jean Grolier bought Lactantius’s Divinarum institutionum libri septem shortly after it was published in 1535, for example; and the 1501 edition of Martial’s Epigrammata was at one time in the library of George III. The display makes reference to a comment made in 1811 that “all the Aldine Classics produced such an electricity of sensation, that buyers stuck at nothing to embrace them!” The fascination continues, as H. R. Woudhuysen observed in the TLS last year.

Details of this and other Aldine events planned for 2015 – including a colloquium at the Warburg Institute – can be found here.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers