What’s so special about Shakespeare’s First Folio?

Photos by DENIS CHARLET/AFP/Getty Images

By MICHAEL CAINES

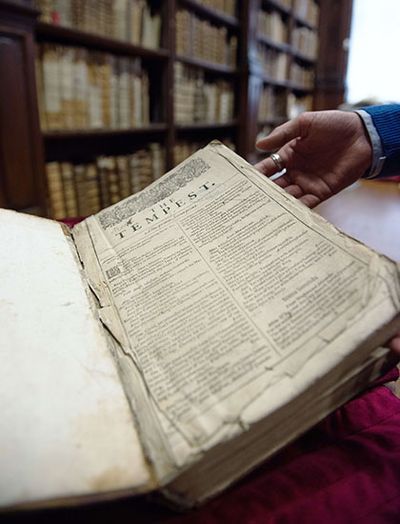

Welcome news from Saint-Omer in the Pas-de-Calais: a copy of Shakespeare's First Folio has been discovered lying unacknowledged in the collections of the Bibliothèque d'agglomération de Saint-Omer, after it was mistakenly catalogued as an eighteenth-century book.

The excitement of the librarian who made the discovery, Rémy Cordonnier, is understandable, and one of the chief experts in the field, Professor Eric Rasmussen, has authenticated the copy and called it "magnificent" – a rare accolade for such a discovery. And Professor Rasmussen, as the author of The Shakespeare Thefts: In search of the First Folios and the co-editor of The Shakespeare First Folios: A descriptive catalogue, ought to know. "First folios don't turn up very often", he has said, "and when they do, it's usually a really chewed-up, uninteresting copy."

The newspapers have duly reached for the estimated price such a book might go for at auction – £4 million, maybe – and the Independent has described the First Folio as being like the "Holy Grail for Shakespearean scholars".

My only qualm is that's potentially a misleading way of putting it. . . .

The Holy Grail is meant to be a unique artefact (let me know when you find it). Individual copies of the First Folio can be, too, for different reasons (but we've already found lots of them). From every existing copy there is meant to be something to be learnt – from annotations, stop-press changes and the like. The Saint-Omer copy has a name written on it in a contemporary hand, that may speak of "Shakespeare's place in Catholic culture", and there are apparently "notes and directions on the play Henry IV", including a change of gender in the Eastcheap tavern, from "hostess" to "host" and "wench" to "fellow", possibly with the practicalities of casting in mind.

By the standards of seventeenth-century drama, I suspect that First Folios are actually more glamorous than genuinely rare. Of something in the region of 800 copies that the experts say were printed in 1623, the Saint-Omer brings the number of survivors up to 233 (about seventy of which have emerged over the century since Sir Sidney Lee's census of 160 copies). That makes it less of rarity than another of Saint-Omer's major treasures, a Gutenberg Bible, which maybe had a print run of only 180 copies, not to mention the library's collection of manuscripts and incunabula.

For those (relatively few?) Shakespeare scholars who need to consult in person a good number of Folios, and can apply for grants and fellowships, the Folger Shakespeare Library has eighty-two copies (while the rest of us have the option of consulting the digitized copies held in New South Wales and Brandeis University, the Bodleian in Oxford; Saint Omer's copy is also to be digitized). Another twelve are at Meisei in Japan; only six of the survivors are still in private hands.

Compare that with the opposite extreme, represented by the Lost Plays Database set up a few years ago. Here's what kept Tudor and Stuart England entertained besides Shakespeare between 1570 and 1642, and of which we know sometimes only a title and a few tantalizing details. "A Bad Beginning Makes a Good Ending" was probably a comedy performed at Shakespeare's company, the King's Men, at Court in the "winter holiday season" of 1612–13. Another company, the Earl of Worcester's Men, may have had another Osric ("Marshall Osric" by Thomas Heywood and Wentworth Smith), around the time of Shakespeare's Hamlet. And wouldn't it be just a little bit interesting to have a snippet of "Strange News Out of Poland", "The Siege of London" or "The Stately Tragedy of the Great Cham"?

And then there are the plays that exist in only a single known copy, such as surviving fragment of the Henry IV part 1 quarto of 1598, or the first quarto of King Lear, of which there are a dozen copies (or at least there were, in W. W. Greg's day).

In other words: Shakespeare First Folios are not the rarest of all rarities, wonderful though the news of another one is. It's just rare to find another one now – 2006 was the last time a complete copy sold at auction, I think. See Emma Smith's review of The Shakespeare Thefts and The Shakespeare First Folios in 2012 ("Take a thief") for the long view of the matter.

Many more plays of the same period, as Lois Potter has pointed out in the TLS ("Theatre before Shakespeare"), were simply never printed – or emerged under different titles, making it difficult to keep track of them, or even impossible to recover anything more about them than the kind of scraps given above. It's probably a safe bet that few of these apparently ephemeral entertainments and masques, as well as comedies, histories and tragedies, were lost masterpieces on a par with King Lear. But all the same, out of selfish curiosity if nothing else, I wouldn't mind having a few of them back – maybe even instead of (as if such a thing were possible) a 234th First Folio. Sheer blasphemy, I know . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers