Peter Stothard's Blog, page 37

October 23, 2014

Leading ladies at Somerset House

By ROZ DINEEN

Somerset House is well liked, and not just in comparison to its near neighbours (Trafalgar Square, Leicester Square, The London Eye) who tend to lack refinement.

Being liked rubs off. It makes a person friendlier. Today in Somerset House's elegant courtyard, the popular annual ice rink is under construction. In the summer, fountains shoot from the floor of the same courtyard, going very high and in various patterns of synchronization, cooling people, delighting children. On summer nights films there are projected onto big screens for a reasonable price. The Coutauld Gallery, nuzzled in at the side, is free and has Michelangelo, Rubens, Rembrandt, Cézanne and Turner.

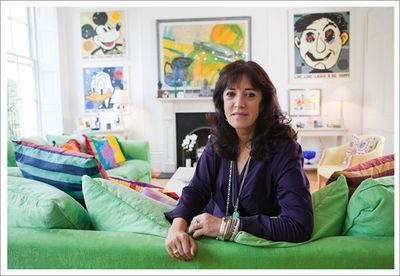

Also free is a small exhibition, currently on in the South Wing, behind the forming ice rink. 100 Leading Ladies comprises portraits by the photographer Nancy Honey. All of the sitters are over fifty and successful in their fields. Germaine Greer is there, as is Diana Athill. Lucinda Lambton is pictured playing the harmonica to her dog. Maggi Hambling drags on her cigarette; wearing a man’s Wrangler shirt and seahorse earrings, she is looking away and up. She is not posing but about to realize something. Lesley Yellowlees, Professor of Inorganic Electrochemistry and the first female President of the Royal Society of Chemistry, is caught laughing, uproariously.

Dame Gail Rebuck DBE. Chair of Penguin Random House UK

On the window ledges of the gallery are reader copies of the book that accompanies this exhibition. Here the photographs are printed alongside interviews conducted with each Leading Lady by the journalist Hattie Garlick.

Diana Athill, recalling the heartache caused by the fiancé from the RAF who dumped her, says, "The pain was almost intolerable". But, "Who knew what would have happened if I had, in fact, married Tony? . . . I might well have been mad. Or taken to drink. Almost certainly an unfaithful wife." Tessa Jowell says, "politicians of my age were forged on steel because the politics were violent, menacing, vitriolic".

Shirley Williams says, “The funny thing is that women are charged with getting emotional, but when it comes to politics, they tend to be much more serious than the men”. She also describes the benefits of communal living. Patience Wheatcroft extols the four day week.

Baroness Afshar OBE. Professor and prominent Muslim feminist

Architects, publishers, doctors and retailers reflect on how they rose up the ranks. Children – the having of or not – are mentioned in almost every instance. Many provide their own definition of feminism before agreeing to it.

Garlick keeps up a subtle conversation throughout so, as you read through, different individuals chime in on the same questions: has medicine become too feminized? Should we have board quotas? What would you advise the young today? The answers, naturally, contradict here and there. The overall impression is a realistic one. Too often examinations of womens' lives provide one-size-fit-all answers and leave little room for individual nuance. This book shows that there are many ways to be successful, commanding and charming among occasionally difficult neighbours.

Helen Bamber. Therapist and Human Rights Campaigner

100 Leading Ladies: A Portrait of Influential Senior Women in Britain by Nancy Honey is at Somerset House until Sunday. Admission is free. The book that accompanies the exhibition is available here.

October 22, 2014

Frieze-frame

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

I spent most of last week at Frieze Art Fair and although much of it was unimpressive – particular low points for me: a worm sculpture made out of cereal-box cardboard; flashing light bulbs spelling out "NOTFORYOU" (just after I saw this there was a powercut in half the tent, perhaps related); a square created from a few hundred pieces of black Lego, mounted on the wall in a bulbous silver spray-painted frame ("This is topical, think Malevich", an art dealer next to me declared. "Aaaah", his clients cooed) – I came across a number of extremely beautiful photographs.

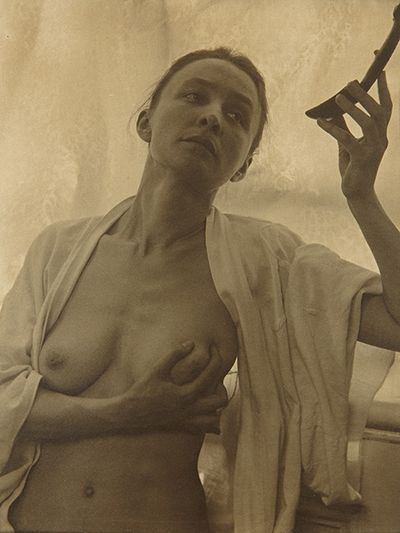

Alongside powerful offerings from Sally Mann, I saw the arresting sepia-stained print, above, of the painter Georgia O’Keefe taken by her husband, the American photographer Alfred Stieglitz, in 1919. The draped material, her intense gaze and pose: she looks like a Rubens statue. And that’s the point. Stieglitz was instrumental in lifting photography to the levels of a fine art form in the early twentieth century, through both his own images and his writing on the subject. He led the Photo-Secession movement that placed importance on the manipulation of the image by the artist to convey a subjective vision – rather than mere photographic documentation – by choice of composition and printing processes, such as the use of gum bichromate to provide a golden tone and visible brush strokes on the surface of the image.

It was a coincidence, then, to find Alvin Langdon Coburn’s haunting, asymmetrically composed print, “Cadiz Harbour”, elsewhere on display in Frieze Masters (there are two tents: one for Frieze London; the other, Frieze Masters, is a fifteen-minute walk across Regent’s Park). Coburn's print was showcased in the first major exhibition of the Photo-Secessionists, curated by Stieglitz, at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1910. Around the same time, George Bernard Shaw wrote of Coburn: “[he] is one of the most accomplished and sensitive artist-photographers now living. This seems impossible at his age – twenty-three; but as he began at eight, he has fifteen years technical experience behind him. Hence, no doubt, his remarkable command of the one really difficult technical process in photography: printing”.

A wonderfully voyeuristic black-and-white image, “Sunny Day, New York, August 12, 1978”, from André Kertész hones in on an unknown woman sunbathing naked on the roof of a New York apartment block. Perhaps it’s the exiled Hungarian artist’s attempt to connect with his unfamiliar surroundings. And I was pleased to see more of Wolfgang Tillmans’s sumptuous “Greifbar” series; the tracing of light on photo-sensitive paper. (Tillmans has recently been elected a Royal Academician in the category of painter, even though his work is photographic.)

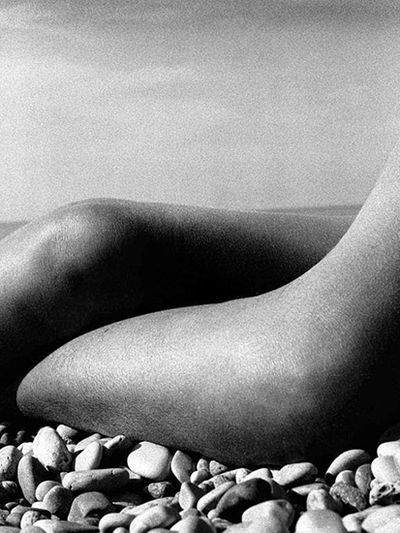

And then I stumbled on Bill Brandt’s poetic black-and-white “Nudes”. Close-ups of stark white curved bodies set against natural landscapes. He chose a wide-angle camera, of the sort used by the police to record crime scenes. It meant he could look at familiar forms from the position of “a mouse, a fish or a fly”, he said. “Instead of photographing what I saw, I photographed what the camera was seeing. I interfered very little, and the lens produced anatomical images and shapes which my eyes had never observed.”

You can see Man Ray’s influence - incidentally, the stand also had a few of these – whom Brandt assisted for several months in Paris during 1930. Ezra Pound, apparently, introduced them. Brandt is also famous for his portraits of Pound and a number of other writers (including Robert Graves, Dylan Thomas, Graham Greene, E. M. Forster and the Sitwells), which were commissioned by publications, such as Lilliput magazine and Harper’s Bazaar.

Meanwhile, over in Frieze London, Marina Abramović could be seen in a white Edwardian-style dress, with neatly parted hair tied back at her neck, sitting on a chair in an expansive cultivated landscape. In her photograph “Places of Power, The Garden of Maitreya”, Abramović offers a welcome moment of contemplative stillness. Not something easily found in the hectic, over-stimulated aisles of the Frieze London tent. As I passed security on my way out, a brass band were playing a mashed-up version of the Popeye theme tune. Perhaps Jeff Koons was behind it.

October 21, 2014

The once and future biographer

By MICHAEL CAINES

In the spring of 1963, Sylvia Townsend Warner received a copy of some privately printed poems "inscribed with immodesty", as she put it: "from an unknown worshipper". Yet these were poems that she liked, as she frankly noted, because they were "of my own way of writing".

The poet duly received a letter of thanks (and Warner could be a wonderfully charming letter-writer of note), but, unfortunately, was to die barely a year later. Warner immediately lamented him as a "friend I never managed to have": he was T. H. White, like her, a novelist as well a poet, and a person she was soon to get to know all too well, not as a friend, but as a biographical subject.

This was a somewhat surprising situation. . . .

. . . and there's a fascinating essay about it, The Cat in the Hamper (now online), by Morine Krissdóttir (the biographer of John Cowper Powys). Dr Krissdóttir raises more general questions about the difficulties of life-writing, which happen to be on my mind at the moment (albeit in relation to a much older and more venerable figure, more of which at some later date, maybe).

Warner had never written a biography before she wrote White's, and she was feeling the age she appears to be in the photo above. Writing was becoming more and more of a struggle. Old friends (including her beloved cat Niou) were dying; she despondently describes herself in her diary around this time as "dead-alive as usual".

As far as I recall, however, in T. H. White: A biography she produced an engrossing, vigorous book, in large measure because Warner soon discovered the sympathetic similarities between her and her subject as well as the significant differences – for her feline Niou, for instance, he had the canine Brownie, whose death had also left him bereft ("Brownie, I am free of you", one poem begins, "Who ruled my heart for 14 years!") – although, as "The Cat in the Hamper" suggests, there may be more and less to it than simple sympathy. Leafing through the book now, I think it does exactly what Warner intended it should do, in that it lets White speak for himself a great deal, whether that means making a minor confession ("I am partially in love with a quite perfect barmaid") or a judgement on Shakespeare ("Pericles is perfectly cinematic, if only Hollywood knew it . . . Titus Andronicus stinks of Marlowe").

White's publisher had approached Warner, out of the proverbial blue, to write a Life of White – a fellow author whose commercial appeal had recently increased dramatically, with the publication of The Once and Future King in 1958, the success of the musical Camelot and the Disney film of The Sword in the Stone, adapted from the first volume of White's Arthurian tetralogy).

Over the next couple of years, she immersed herself in his books, his letters and his diaries (including his red-inked dream diary), visited his house on the island of Alderney, consulted with his friends and his loyal publisher, discovering the self-tormented man permanently traumatized by the "thwacking regime" of his schooling at Cheltenham College, perennially lonely and driven to work as a means of fending off the demons of alcohol and pent-up sadism. Reading the later diaries, Warner told her friend and New Yorker editor William Maxwell, was "like feeling at home in hell".

Some of this potentially controversial information called for the advice of mutual friends, such as David Garnett, and there was clearly plenty of wrangling and revision during the production process. The possibility of being sued for libel could not be ruled out. The unknown worshipper had become a rather dangerous kind of muse.

"Presumably", Krissdóttir remarks, "Cape wanted a biography that would increase White's readership not repel it." I'm reminded of the dodgy dossier about Swinburne, another writer with a taste for drink and flagellation, that Edmund Gosse circulated among a small circle of his peers, seeking their advice on what to do with it; as a result, the Gosse biography has its charms but the whole truth it is not. By contrast, here's Garnett's radical suggestion to Warner, which might make interesting reading for anybody wondering about the shaping of a literary biography and the gradual evolution of a reputation over the years:

"You must write your book without thinking about anyone's feelings. Then when you have completed your masterpiece, you can bowdlerise the 1966 edition, knowing that the whole thing will appear in 1996 and that there will be long reviews saying that you were not only a poet, not only a master of the short story, but the most brilliant and perceptive biographer of the era . . . ."

Flattering stuff. (And it makes me wonder, although Warner went her own way in the end, which, if any, I wonder, of the literary Lives of the 2000s will appear in thirty years' time with the long-dead scandals restored?)

In the end, Warner found it extremely difficult to let go. "Sometimes as I handle these mss, note-books, letters, the sense of his existence – that he handled them, knew the look of them – almost overwhelms me", she wrote in her diary in 1966. "I think, I shall die when these are withdrawn: they are mine, he bequeathed them to me." A biographer possessed and possessing – is that the way it always is?

October 17, 2014

The hotel and the writer

By THEA LENARDUZZI

When I arrived at the Midland Hotel, the marble foyer was bustling with a coachload of French tourists (“unexpected”, the concierge said) and a pianist was working his way with brio through jazz standards – rather different to the place which, Olivia Laing tells us, W. G. Sebald found on his visit in the 1980s. Back then, she says, “it was on the verge of ruin, the once-legendary heating system erratic, the water full of rust”.

What I didn’t go into in my earlier post on the Manchester Literature Festival was the surprising link between the Midland and literature. After all, a hotel, with its constant comings and goings, seems a rather unlikely place to give way to the hush of a literary event. But this one, it turns out, is a very bookish place, with its own writer-in-residence programme – as most places, public or otherwise, do these days, from airports and hospitals to prisons and – boasting site-specific commissions by Patricia Duncker, Jackie Kay and Adam O’Riordan (you can download their pieces here). Laing, this year’s writer, presented the fruits of her stay “in a large hotel in a large city in the north of England” to a gathering of festival goers last week, over afternoon tea.

I read Laing’s short story “The Other Hotel” on the train up. It wasn’t until I got off at the other end that her words began to find their reflection in my new surroundings: “I like Manchester”, she writes. “Canals and rain, things running into one another. A city on the slide, tumbling perpetually through cycles of ruin and renewal, building cropping up and falling down and being restored, the ghosts of millworkers wandering bewildered through gleaming museums and pizza parlours.” (Though, to underline a point in my previous blog, the weather was glorious.)

Laing’s story hinges on the discovery, during the vast refurbishment that followed Sebald’s stay (he had predicted it would become a Holiday Inn), of “ephemera that had gathered over the years”, Christmas cards, silk stockings, currency from long gone countries – and love letters sent between a married woman, Mabel, and a down-at-heel artist, Gordon. (These are displayed in frames dotted around the hotel’s corridors.)

Laing – whose books include To The River (a biography-cum-travelogue) and The Trip to Echo Spring (in part a group biography of writers who drank to excess) – seems interchangeable with her narratorial “I”. In the hotel, Mabel (“smelling of apples and bonfires, as the dead often do”) and “I” mingle (“‘By the way, what are you doing in my room?’ ‘It's my room’, she said”). The story is a clear, often witty, meditation on the biographer’s predicament: “I’m trying to write about dead people sympathetically, to explore all these issues, you know, privacy and exposure … and she says there is no past and I say okay but there is … and she says where and I say well everywhere, here”.

When we read, at the end of a typically lively exchange between the two, “I’m writing your biography”, there is a sense of roles having come unstuck. Who is bringing out the what in whom?

What remains clear throughout Laing’s story is the strong foundation on which a relationship between location and literature is built. Here, place shapes expression and colours imagery: the often unpunctuated exchanges between Mabel and the narrator mimic the latter’s rambles through the labyrinthine corridors of the Midland, while the unknowable in each conjures the building itself “built in the shape of a figure eight, around two light enormous light wells, twin abysses”.

October 16, 2014

Nobel laureates: France in the lead

Sully Prudhomme

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The French response to the award of the Nobel Prize to Patrick Modiano combined pleasure with surprise that a second writer from that country should be so honoured only six years after J. M. G. Le Clézio. The latter was praised as an "author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization" – yes, it’s guff isn’t it, even if Le Clézio undoubtedly has had his fine moments as a novelist. Modiano on the other hand has been commended "for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation" – something lost in translation maybe.

The TLS’s eloquent champion of Modiano, Henri Astier, also pointed out that the Nobel Committee’s comparison of Modiano’s work with Proust's was rather wide of the mark. (Apart from anything else, it could be said that all of Modiano’s novels are on the short side, comfortably under 200 pages mostly.)

Staying with France, I would have put both Marguerite Duras (who died in 1996) and the nonagenarian Michel Tournier ahead of Le Clézio and Modiano. Tournier’s chance has definitely gone and he’s probably not the kind of writer the Nobel Committee go for: too left-field and transgressive (maybe the same could have been said for Duras).

I wonder if it’s mere idle boasting, or perhaps a symptom of national insecurity – the economy’s tanking, unemployment continues to rise, while the CEO of John Lewis recently said some extremely disobliging things about their capital city – that Le Monde newspaper felt the need to point out that the French head the Nobel list in terms of laureates with fifteen? (It would be sixteen if they included French-language writers as they could then add the Belgian Maurice Maeterlinck). From the first laureate, Sully Prudhomme in 1901 (I will get round to reading him one of these days), via some notable omissions, to Camus, the refusenik Sartre, Claude Simon, Gao Xingjian (2000 – resident in France and writes in Mandarin and French so they’re claiming him) to Le Clézio and Modiano.

Second on the list are the United States, which Le Monde credits with twelve; I counted ten, including Isaac Bashevis Singer who wrote in Yiddish (twelve if you include the exiles Czeslaw Milosz and Joseph Brodsky). Britain meanwhile is given third place with ten. Again, I counted eight, excluding four Irishmen (Yeats, Shaw who was admittedly long resident in the UK, Beckett and Heaney). Then there are Tagore (Bengali and English), the Australian Patrick White, the Nigerian Wole Soyinka, the South Africans J. M. Coetzee and the late Nadine Gordimer, and the Saint Lucian Derek Walcott.

I’m on a roll now: Italy boasts six by my reckoning (the most recent being the utterly surprising Dario Fo). Spanish-language writers make up eleven (five Spaniards, two Chileans, one each from Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico and Peru); there is just one Portuguese (José Saramago, in 1998) and no Brazilians. The German-speaking nations have thirteen (of whom ten Germans, by my calculations).

The Scandinavian countries score well with thirteen (of whom seven are, unsurprisingly, Swedish). Russia/the USSR, on the other hand, doesn’t score very highly (excluding the exile Brodsky, I make it four), while Poland has either three, or four (Milosz again). There’s a brace of Greek poets – George Seferis (1963) and Odysseus Elytis (1979), but only one Arab-language writer (the Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, 1988). Canada has only one (Alice Munro, 2013; although Saul Bellow was born in Montreal), which is surprising for such a literate nation. Japan has two.

That’s almost it, but, frankly, who’s counting? After all, literature recognizes no borders. Place your bets for next year.

October 14, 2014

Manchester, Dylan Thomas and a dark room

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Manchester Literature Festival is in full swing with a programme of events taking place in libraries, theatres, music halls and hotel rooms (in the Midland Hotel, to be specific – but more on that in a future post), dotted around the city centre. Arriving on Saturday at around midday, I knew I’d already missed plenty: the Spanish writer Andrés Neuman discussing his new novel; Lorna Goodison and Kei Miller reading their poems to the jazz-trumpeting of Matthew Halsall; Sebastian Barry and Colm Tóibín on the state of the Irish novel.

It was a twenty-minute walk from Manchester Piccadilly, down the main student thoroughfare of Oxford Road, to the Martin Harris Centre for Music and Drama – a modern performance space set in the heart of the oldest part of the University’s campus. The sun was ablaze, eliciting a rich copper glow from the red bricks of Manchester.

Though the main concert hall has room for a full symphony orchestra, on Saturday it hosted just two men – the Dylan Thomas aficionado Jeff Towns and the artist Peter Blake – and a laptop, from whence was projected a sequence of Thomas- and specifically Under Milk Wood-related ephemera.

For at least thirty years, Blake explained, he has nurtured “an obsession” with the poet’s “play for voices” – ever since “John” chose Thomas for the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (you’ll find him propped up between Aldous Huxley and Terry Southern). This obsession – his others include Ian Dury memorabilia (Dury studied under Blake at the RCA) and dwarves (he owns a pair of boots worn by Tom Thumb, Queen Victoria’s favourite) – has taken the form of over 100 pencil portraits, watercolours, collages and found images conjuring Thomas’s “darkest-before-dawn” town and its characters.

These have now been published in a book alongside the definitive text to mark the centenary of the poet’s birth – of which Blake was apparently unaware until Towns mentioned it last year. Listening to the artist speak fervently about the endless, generally ribald, “layers” of his subject, however, one gets the sense that this collection – first exhibited at the National Museum Wales in Cardiff and now at Oriel y Parc in Pembrokeshire – is itself anything but definitive. For Blake continues to be drawn to the dream sequences and realities of the inhabitants of the fictional town of Llareggub (a composite of all the seaside towns Thomas had ever visited, Towns and Blake agreed).

Like Thomas, he began at the beginning, sketching First Voice and Second Voice – copied from photographs of Ted Hughes and Humphrey Bogart respectively – and continued until the entire cast had been set to paper, from the blind Captain Cat (see below: less the Peter O’Toole of the 1972 film adaptation, more Uncle Albert from Only Fools and Horses) and his beloved Rosie Probert, to Nogood Boyo (who, incidentally, looks nothing like David Jason, who took the role in the same film) – and every butcher and baker in between.

From Peter Blake, Under Milk Wood (London: Enitharmon Editions, 2013) (c) the artist.

Next, Blake turned his attentions to the poem’s imagery, “interpreting each one literally”. And so we have, “In Butcher Beynon's, Gossamer Beynon, daughter, schoolteacher, / dreaming deep, daintily ferrets under a fluttering hummock / of chicken's feathers in a slaughterhouse that has chintz / curtains and a three-pieced suite, and finds, with no surprise, / a small rough ready man with a bushy tail winking in a paper carrier”:

From Peter Blake, Under Milk Wood (London: Enitharmon Editions, 2013) (c) the artist.

And for “. . . titbits and topsyturvies, bobs and buttontops, bags and / bones, ash and rind and dandruff and nailparings, saliva / and snowflakes and moulted feathers of dreams, the wrecks / and sprats and shells and fishbones, whale-juice and moonshine / and small salt fry dished up by the hidden sea” (Blake’s personal favourite because of the technical challenge of illustrating dandruff), we have this:

From Peter Blake, Under Milk Wood (London: Enitharmon Editions, 2013) (c) the artist.

That’s what great radio can inspire, I suppose, yet I couldn’t help but lament the absence of Richard Burton’s honeyed tones (for, having played First Voice in three of the four radio productions as well as in the 1972 film, he seems inseparable from it).

That evening, Edgar Allan Poe – who appears just above Thomas on the Sgt. Pepper cover (sandwiched between Carl Gustav Jung and Fred Astaire) – played a part in one of the pieces comprising In the Dark, “a collaborative project between a new generation of radio producers and radio enthusiasts” that has the ultimate aim of bringing about a “mini-revolution” in spoken-word radio (the pieces were played, as you may have guessed, with the lights off). Where Thomas worked his biographical vignettes into a rich and steaming pat, In the Dark ran a sequence of discordant “audio explorations”, each one self-contained: in the Poe piece, the famous circumstances of the author’s death in Baltimore, Maryland, were reimagined; in “Thirteen Ways”, the radio producer Pejk Malinovski transported us to a class full of boisterous eleven-year-olds in Queens, New York, and set about teaching them Wallace Stevens's poem "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird" (the word “indecipherable” proves just that); in “Books”, a bibliophile sorted through his burgeoning collection (“The book of family games can go . . . they never come round anymore”); in “Remedial Theory”, the producer Benjamin Walker travelled from America to the Hague, where Slobodan Milošević was on trial for war crimes, to deliver his own selection of books to this “avid fiction reader” (the premiss being that, if reading literature encourages empathy, “Milosovic must be reading the wrong books”).

The lights came up and I set off back along Oxford Road, its buildings now a deep shade of aubergine; I felt I’d done a fair amount of travelling for one day.

Manchester Literature Festival runs until October 19.

October 13, 2014

Poetry and social change: Storymoja

Vuyelwa Maluleke at Storymoja

By ZOE CORMACK

Storymoja is one of the biggest literary festivals in Africa. This year, the patron of the five-day literary event at the Nairobi National Museum was Auma Obama, the sister of Barack. Wole Soyinka headlined and around 170 writers and performers from across (and beyond) the continent of Africa were in attendance.

I had come to Storymoja, I must confess, with an academic hat on to attend a panel on the provisions for culture in Kenya’s new constitution (which two members of my research team were taking part in). But I happily used the opportunity to catch a glimpse of what was going on in the Kenyan literary scene.

Storymoja provides a space for new African writers to get exposure at an international event; it also aims to nurture a young generation of writers and promote a reading culture in Kenya. To this effect, the first three days of the festival had been allocated to schools and merry bus loads of pupils from across the country swarmed around the stalls, taking part in workshops with the visiting writers (who seemed to be enjoying the challenge of the young audience).

As well as the giddy children, Storymoja exhibited some of the laid back cool you might expect from Nairobi’s young literary avant garde. For many attendees, poetry was the order of the day. I caught snippets of the truly wonderful performance poetry of South Africa’s Vuyelwa Maluleke and other poets affiliated with the African Poetry Book fund and the BN Poetry Awards – whose founder, Beverly Nambozo, described how she’d set it up after years of frustrating work at an NGO. Poetry, she had decided, was a more meaningful way of creating social change.

The panels touched on other aspects of contemporary Nairobian life – in one of the best attended, entitled “The Future of Men in Kenya”, young male speakers voiced concerns about the erosion of men’s rights. They were promptly put in their place by the audience, which was largely comprised of young Kenyan women. Even the British High Commissioner entered the fray, participating in a panel chaired by the Nigerian-American author Teju Cole on art and democracy and posing for selfies with the photographer Boniface Mwangi.

There was plenty of discussion about the state of the arts, funding and expression in Kenya. In one amusing anecdote, the musician Eric Wainaina (famous for a song complaining about corruption – “Nchi ya kitu kidogo” – “Country of bribes”) described how he’d been leapt on by NGOs trying to get their messages across to the Kenyan public. He was contracted to write a song about the Millennium Development Goals and realized this meant he needed to start thinking about things like how to get the word “sanitation” into a song.

The festival started in 2007 as the Storymoja Hay Festival – a part of the global Hay collective. This year it was a Hay festival no longer. Storymoja’s founder, Muthoni Garland, described this as an emancipation of sorts. She explained that it was important for Storymoja to go it alone: to carve out the festival’s own space and become more Afrocentric.

Perhaps some of this need for greater ownership has come out of tragedy. Last year, the final day of Storymoja, at which the Ghanaian poet Kofi Awoonor had been scheduled to perform, was cancelled following his death in the Westgate Mall attack. Many of the artists present this year had also been at the festival last year and this seemed to make it, both for them and the organisers, a site of memorial. Some writers spoke about a need, a compulsion, to return to Storymoja. In a very affecting memorial address Kwame Dawes (a close friend of Awoonor) considered how the poet himself would have decried the disregard for human life that unfolded in Westgate.

There are still many unanswered questions about Westgate, a fact that has not gone unnoticed by many Kenyans. There has been no public investigation and Kenyan Somalis have become the victims of recriminations after al-Shabaab (the Somali militant organization) claimed responsibility for the attack. In this context it is not surprising that a literary event can also provide a forum for political debate. Many at Storymoja were keen to take art to bear on social justice. How and on whose terms remains a question. As Eric Wainaina pondered, does anyone actually want to dance to the sanitation song?

October 11, 2014

Patrick Modiano: a worthy winner

Patrick Modiano, 1981. Credit: Jean-Pierre Couderc / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

By HENRI ASTIER

Patrick Modiano has been a national literary treasure in France for decades. But it took a Nobel Prize for the rest of the world to notice him. This relative international obscurity has always baffled me. Before I even opened my first Modiano novel at the age of eighteen, I was struck by the title staring from my parents' bookshelf, Livret de famille. It had both a bureaucratic simplicity and a dreamy ring to it.

From the first page I was enthralled. My fascination was widely shared: few in France were surprised when Modiano's next novel, Rue des boutiques obscures (another ethereal, Modianesque title), won the 1978 Goncourt prize.

Every book he has written – at the rate of about one every two years over almost five decades – has enjoyed both huge sales and unanimous critical acclaim. So why were the cultured classes in other countries, usually so quick to embrace French fashions, ignoring such a genius? Perhaps they actually knew better, I wondered. Was the world right and the French the victims of a collective hallucination?

But no. Soon after I moved to London as a fledgling journalist in the early 1990s, I made it my mission to spread the word about my literary hero. The TLS has published half a dozen reviews of Modiano novels by me. Although not exactly a vox clamantis in deserto, I cannot claim success in my evangelization effort. Not a single one of the novels I reviewed has so far been translated.

So why has global recognition taken so long? And why did it to have to come from above, from the most august of panels, rather than emerge from below – as we are told is increasingly the route to fame in this networked world? There is an online "Réseau Modiano" http://reseau-modiano.pagesperso-orange.fr/ . But it is small – it has been temporarily crushed by the weight of the Nobel announcement – and all its contributors are French.

Part of the reason for Modiano's low international profile is that he is a recluse. In a world where self-promotion is key to success, he does not go on publicity tours. Neither does he travel the world, joining discussion panels with the great and the good. During his rare appearances on TV he has been tongue-tied.

More fundamentally, there is a quality in Modiano's prose that does not to travel easily. His stories are not the kind that just tell themselves.

I recently tried to summarize a typical Modiano story for the benefit of a British publisher. I wrote something like: "It is the story of a young man in 1960s Paris who has been cast adrift by a fugitive father. He is a draft-dodger who lives by his wits. After being questioned over a case that is never made clear, he meets a girl at the police station. Drawn by the mystery that surrounds her, he takes both the girl and her suspiciously heavy suitcase into the apartment vacated by his father. Through her he meets various shady people, who lure them into assisting what looks like a kidnapping (we're not sure). Sensing imminent danger, they decide to escape abroad, but the girl is killed in a car crash as she goes to retrieve another suitcase with her 'savings'".

Clearly, the nebulous storyline will not have publishers falling over themselves to compete for the translation rights, or movie companies for the film rights. But of course Modiano's plots – minutely crafted as they are – matter much less than the feelings evoked by his deceptively simple style. He writes in short sentences, often without a verb – here the Nobel jury's praise as "a Marcel Proust of our time" sounds slightly contrived.

But the panel was right to highlight memory as Modiano's main theme. His narrators look back at the past through a glass darkly. They try to rescue half-remembered events from oblivion before it is too late – either other people's wartime experiences recorded in an incomplete trove of documents (as in Dora Bruder) or more typically disjointed events from the protagonist's youth still that haunt him.

The lack of narrative clarity goes hand in hand with geographical precision. We know exactly where events take place – and each specific neighbourhood, or address, is laden with layers of successive memories. Behind the Paris of the 1960s lies the Paris of other times in the narrator's life, and his father's Paris under the Nazi occupation. The cadence of sentences and the music of place names are also central to Modiano's touch. The poetic character of his writing is another reason why few have ventured to translate him so far.

But by definition, the appeal of all great authors is universal. Language barriers are there to be crossed. Let us hope that Modiano's anointment by the Swedish Academy will encourage translators across the world to finally have a go.

October 10, 2014

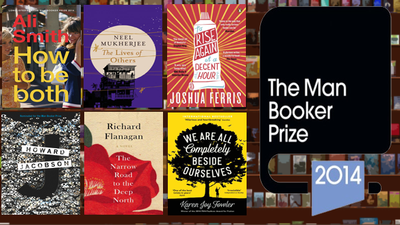

A prize every time

The winner of this year’s Man Booker prize will be announced next Tuesday. Those prone to a flutter might find their way to the website Oddschecker (“your best bet”), where the shortlist is ranked. Currently Neel Mukherjee is in the lead with The Lives of Others followed by Richard Flanagan's The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

The professional gambler would do well to look beyond Oddschecker to the TLS for some carefully considered reviews of the shortlist (all of which have been made publicly available in full, through the links below) because the TLS has got it right before – not always, but often enough. . . .

Take the issue of May 15, 1981, when Valentine Cunningham wrote:

What makes Midnight’s Children so extraordinarily important, and moreover (for literary importance isn’t always matched by a fetching readability) what makes it so vertiginously exciting a reading experience, is the way it takes in not just the whole apple cart of India and the problem of being a novel about India but also, and this with the unflagging zest of a Tristram Shandy, the business of being a novel at all.

The Booker judges subsequently agreed; not once, but twice.

And here is Oliver Reynolds on Graham Swift, in the TLS of January 19, 1996:

Last Orders is his finest book to date; emotionally charged and technically superb, it is a wonderful example of the novel’s power to resolve the wavering meanings of the life we all share into a definite focus, one where the clarity with which things are seen renders them precious. Swift’s central strength as a writer is his integrity . . .

Dear reader, he won.

But this is Barbara Hardy reviewing the soon-to-be Booker Prize winner of 1984, Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac:

The novel is as amiable as the heroine, though its charm seems drier. The style, at its best in dialogue, can be sharp and fast. It is not so good on emotional narration.

And here is the TLS on the very first winner, P. H. Newby’s Something to Answer For, back in 1968, when reviewers were anonymous:

Mr. Newby’s novel remains rather on the level of brilliantly resourceful entertainment.

The TLS reviewer may not always align with the sentiments of the judges. But, like the judges, the reviewer has rooted to the base of each book on the shortlist, expanding the scope of its questions, and pursuing the offered pathways through it to their sometimes logical conclusions.

While we are not party to the panels’ digressions and arguments we can follow those of the reviewer and embrace, disagree or place our informed bets from there.

So, without further ado we present the TLS on this year's Man Booker shortlist:

Kate Webb reviewed Ali Smith’s How to Be Both:

On Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, Alan Murrin found that:

On Neel Mukherjee’s The Lives Of Others, Alex Peake-Tomkinson wrote:

Bharat Tandon reviewed Howard Jacobson's J:

Ben Eastham on To Rise Again at a Decent Hour by Joshua Ferris:

Craig Raine reviewed Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North:

Now – place your bets . . .

100 good godly reads

Saint Augustine in His Study by Sandro Botticelli, c1490-1494

By RUPERT SHORTT

It felt like a theological Desert Island Discs writ large. Or a literary version of the Solomon’s-baby challenge. Eight of us – theologians, clerics, a librarian and a journalist (me) – were given a portentous remit by the Church Times: to select the “100 best Christian books”. . . .

The template is hardly untarnished. It almost goes without saying that on TV, especially, menus for the 100 best sitcom moments, or rock albums, or lowest common denominators, tend to be safe and stale. Was the answer to go unapologetically highbrow? Probably not. Focusing too much on the view sub specie aeternitatis at the expense of what is popular today seemed equally misplaced – not to say presumptuous. Our list (it has been unveiled in stages over the past fortnight, with the top ten appearing today) contains the spiritual equivalent of tea and squash, side by side with Barolo or Single Malt.

The wine and whisky analogy tells us more besides. We grant that ours is a mainly European list with a heavy Anglophone bias. All the judges apart from me were Anglicans; we’re all too aware of how random our choices will seem to many. The arbitrariness was softened somewhat along the way, though. First, the Church Times’s Editor, Paul Handley, sought pitches from more than a hundred of the paper’s reviewers. Their nominations led to a long-list of 700 titles, and then a shortlist of 120 based on the number of times a given work was proposed. Before meeting in June, the judges (chaired by Martyn Percy, the new Dean of Christ Church, Oxford) ranked the shortlisted works in sextiles – which should be in the top twenty, which in the top forty, and so forth. From this stage a preliminary ranking emerged.

The impact of a given work was judged important, though not sacrosanct. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs is a case in point. Though hugely influential in its time and thereafter, it is little read today by non-students and was eventually demoted to eighty-eighth place on our list. The Bible and liturgical works – the Book of Common Prayer and Hymns Ancient and Modern, for instance – were excluded entirely on the grounds of forming such a deep part of church life already.

Large-scale systematizations of Christian belief seemed relatively easy to place. St Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae is third, Sarah Coakley’s God, Sexuality and the Self sixty-fifth, and John Macquarrie’s Principles of Christian Theology eighty-third. Devotional verse and fiction were also popular. I was pleased to see included the Complete Poetry of George Herbert (tenth), T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets (eleventh), St John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul (fourteenth), Paradise Lost (sixteenth), the Collected Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins (seventeenth), The Brothers Karamazov (twenty-third), Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (seventieth) and Dorothy Sayers’s The Man Born to Be King (seventy-fourth).

The preponderance of male writers in a tradition dominated by patriarchy, despite some striking exceptions, was obvious and, sadly, unavoidable. But classic texts written by women were not overlooked. Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love is ranked fourth, St Teresa of Avila’s Interior Castle is twenty-fifth, Simone Weil’s Waiting for God thirtieth, Elisabeth Schussler-Fiorenza’s feminist classic In Memory of Her thirty-fourth, and the Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson seventy-seventh.

At the very top stands a unanimous choice: Augustine’s Confessions. Through its stylistic force and sharpness of perception, both psychological and intellectual, this work is still arguably the greatest of all literary self-portraits. For over a millennium, almost all educated people in the Latin West were steeped in this and other works by the fourth- and fifth-century pagan convert who transposed Platonism into a Christian key and ended his days as Bishop of Hippo in north Africa. Augustine is also the only person to feature twice in the top ten: his magnum opus, The City of God, is eighth.

The other top ten works are St Benedict’s Rule (two) – a colossally influential shaper of Christian culture, not only of those called to the religious life – Dante’s Divine Comedy (five), Pascal’s Pensées (six), John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (seven) and Thomas à Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ.

Asked to nominate one that got away, I opted for Shusaku Endo’s Silence (1966), a searing historical novel documenting the Christian experience in seventeenth-century Japan. Its focus on costly discipleship, including martyrdom, gives the work a melancholy resonance in our own time.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers