If buildings could talk

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“Hello. Lovely to see you. Yes you. I’m this building here, the Berlin Philharmonic. I’m fifty years old . . . .” We’re on top of a stegosaurus-like roof – or, rather, the camera is – and the building is speaking to us in a female voice with a German accent: “Buildings have more influence on the world than you let yourself think . . . ”. This is the first of six short films in Cathedrals of Culture, the most recent 3D-film project by Wim Wenders, which had its UK premiere at the Barbican last week.

Wenders and five other filmmakers have each chosen a landmark building (the Berlin Philharmonic; the National Library of Russia; Halden Prison, Norway; the Salk Institute, California; Oslo Opera House; and Centre Pompidou, Paris) and use film to uncover their “soul”; exploring what the buildings are like behind the scenes, after hours, why and how they were built, and their impact on people and cities.

It puts architecture, and 3D-filmmaking, centre stage. According to Wenders, the viewer is immersed “like never before into a place” and the buildings “speak for themselves”. In fact, it’s not such a new device – it reminded me of Old English poetry, where you’re hard pressed to find a text that doesn’t give a voice to an inanimate object.

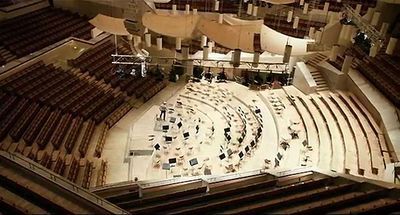

Wenders's take on the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall consists of extended panning shots fetishizing sections of the inside and outside of the building. Initially we are led by a child entering the space for the first time, then by one of its workers (a woman repairing the vibrant blue tiles on the tessellated floor of the entrance area, damaged by “women’s’ high heels”), then by Sir Simon Rattle (the orchestra’s principal conductor), and finally we follow the architect, Hans Scharoun (who died in 1972) – his bust morphs into a black and white hologram, with a cigar hanging characteristically from his lips.

Inside the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall

Inside the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall

After being banned from practising – he was labelled a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis – Scharoun designed the Philharmonic, the building tells us, as a “utopian image of society, for all walks of life” in a desolate part of West Berlin. It’s now the “beating heart” of the city’s culture district. The design is based on three interconnecting pentagrams, with the orchestra and conductor in the centre of the concert hall – which had never been done before; each audience member has an equal view, and every seat can be reached from every seat – there are no elite boxes. The space is cavernous, like an “ocean liner”, but feels festive and light like a circus tent.

A slightly sugary end (“I stand now in what has become a new city, a new country if you like”) moves us into the next film, created by Michael Glawogger about the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg. The camera takes us through shelves and shelves of battered bound books. And, as if acknowledging our presence, the overhead fluorescent lights flicker on as we pass. Overlapping voices, in both Russian and English, read extracts from texts, including Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Joseph Brodsky’s I Do Not Speak and St Augustine’s Confessions.

National Library of Russia, St Petersburg

National Library of Russia, St Petersburg

There are brief moments of comedy when Glawogger settles on librarians wearing dated green overall dresses: one monotonously stamps slips next to a wall covered in her pictures of cats. The film closes with a question about the future of the Library – the camera zooms into the screen of an e-reader left on a library desk and cuts to crowds of people and harsh-beeping traffic on the streets outside the building.

There’s a moving, at times troubling, portrait of Norway’s high-security prison, described as “the most humane in the world”; Robert Redford’s film explains the term “genius loci” – the subjective existential quality of a space – in relation to the Salk Institute designed by Louis I. Kahn; Oslo’s Opera House, which sits like a beautiful iceberg next to a fjord, asks us to “imprint [our] steps into my marble memory”; and Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ Centre Pompidou art gallery is presented as a “cultural machine” that shocked Paris out of its architectural sleep. “Even in darkness, empty of people, I’m full of sound.”

Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

Salk Institute, La Jolla, California

As part of the Barbican's Constructing Worlds season, Cathedrals of Culture opened the cinema series exploring how film engages with buildings and urban life. The programme includes more well-known films (Woody Allen’s Manhattan; Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine; Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing), alongside essay films, documentaries, and newly restored silent films from the 1920s accompanied by live piano. There’s also a film about the brutalist Barbican complex itself from the directors Ila Beka and Louise Lemoine – they’re responsible for an excellent documentary series, Living Architectures, that lets us see the “real life” beauty of iconic, contemporary buildings (usually seen as formidable and detached from human contact).

Cathedrals of Culture does this, sometimes successfully, sometimes not (the entire film pushes three hours – there’s a limit, I discovered, to how much 3D your eyes can take before you feel nauseous). But Beka and Lemoine’s grounded reality is not really Wenders’s calling card. Think of Silver City (1968) – one of his early short films which is an extended shot of a Munich street as viewed from a window ledge, the only movement coming from cars and pedestrians – and the visual worship of buildings in Wings of Desire (1987). What we're asked to think about is the idea that buildings do speak to us – and we should let them.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers