Peter Stothard's Blog, page 29

March 6, 2015

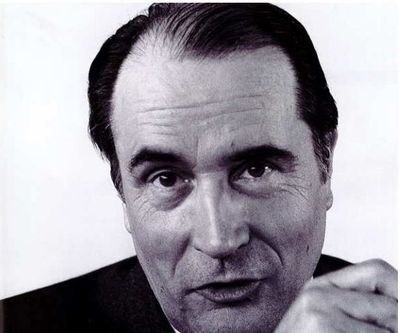

Who was François Mitterrand?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Was there a more mysterious, unfathomable politician in the Western world in the second half of the last century than François Mitterrand? Not for nothing was he known as the “Sphinx” (that enigmatic smile) or the “Florentine” (for his Machiavellian cunning). When he described Margaret Thatcher as having the “eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe”, he managed to combine sexual flattery with cold insult. What, I wonder, did la dame de fer make of the observation?

These thoughts were prompted by the arrival in the office this week of a new, amply illustrated biography by Michel Winock (423pp. Gallimard. €25) of France’s first Socialist president. The author has previously published well-received Lives of Clemenceau and Madame de Staël, while his Flaubert was favourably reviewed by Kate Rees in the TLS of May 31, 2013). As France’s second Socialist president struggles to make an impact in troubled times, Winock’s very readable book seems strangely pertinent. Or maybe it’s that the fascination with Mitterrand has never quite faded.

Reviewing a 600-page English biography of the man – yes, another one – by the BBC journalist Philip Short (subtitled “A study in ambiguity”; TLS, May 30, 2014), Sudhir Hazareesingh wrote “By the time [Mitterrand] retired in 1995, he had become the very symbol of institutional continuity and political longevity: his was the longest period of rule since the reigns of Napoleon III and Louis Philippe . . . . this first Socialist presidency marked the apogee of the republican monarchy in France – a delicious irony given that one of Mitterrand’s most captivating pamphlets . . . was Le Coup d’état permanent, in which he denounced the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the executive”.

That longevity spanned two seven-year terms as president, after two unsuccessful campaigns – in 1965 he polled 45 per cent, losing to de Gaulle, and in 1974 he managed 49 per cent against the lordly Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (he gained his revenge over Giscard seven years later). The presidential term has since been reduced to five years, to avoid the awkward periods of cohabitation between a president and a prime minister from opposing political parties – an awkwardness Mitterrand was adept at exploiting.

I didn’t know until I read Winock’s book that Mitterrand was endorsed without enthusiasm by the spokesman of the Left Jean-Paul Sartre (who died in 1980): “voting for Mitterrand . . . is a vote against a flight to the right by the Socialists. Many will vote for Mitterrand without illusions and without enthusiasm”.

But there were undoubted achievements: the abolition of the death penalty, the introduction of the minimum wage (le SMIC), further European integration, rapprochement with Germany (undermined by a later ambivalent response to the fall of the Berlin Wall). And then there were the big cultural projects: the installation of I. M. Pei’s Pyramide du Louvre, the new Bibliothèque nationale, the Opéra Bastille, etc. His first official outing as President was to the Centre Pompidou and later that year he attended the Arts Festival at Aix-en-Provence.

And he was, lest we forget, the most literary of presidents, a man of culture who would always read on plane journeys and counted Marguerite Duras among his friends (it is said that François Hollande doesn’t read). His first presidential investiture was attended by the novelists Yachar Kemal, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, Julio Cortázar, William Styron, Elie Wiesel (with whom he co-wrote a book) and Melina Mercouri among others.

Against all this has to be placed the fact that, in a move to split the Right, he introduced proportional representation, thereby giving Jean-Marie Le Pen's Front National a foot in the door. We can see the consequences of that today, alas.

Mitterrand’s reputation was dealt a severe blow by the publication in 1994 of Pierre Péan’s Une Jeunesse française, in which the author shed light on his wartime associations with Vichy – Mitterrand even accepted the Francisque, Vichy’s highest honour, an act that Winock says he later regretted. But, as is well known, Mitterrand went on to become active in the Resistance, and later saw no contradiction in this progression: after all, both Pétain’s Vichy and the Resistance were, in their differing ways, defending the nation. And to those who ended up on the wrong side, according to Winock, he showed unswerving loyalty, placing friendship above political expediency.

But this stubbornness was costly to his reputation: as Winock reminds us, the President would annually place a wreath on Pétain’s grave, and maintained a friendship with René Bousquet, the man who oversaw the Vel d’Hiv round-up in 1942. Winock quotes Pierre Moscovici, until recently finance minister in Hollande’s government: “as a Frenchman and as a Jew . . . what shocks me is that in 1994 Mitterrand admits to having kept in touch with René Bousquet up until 1986”. (Bousquet was assassinated in 1993, before he could stand trial for crimes against humanity.)

Then there was the fact that he kept his medical history secret from the public, having been diagnosed with prostate cancer not long after he became President. And of course the revelation of the second family (maintained at taxpayers' expense), when Paris-Match published photos of the president with his daughter Mazarine Pingeot in 1994. He was a seducer in the tradition of French heads of state, in spite of his relative lack of height (Winock puts it at 1m 70 – there is a thesis to be written on tall post-war French presidents, such as de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, Giscard, Jacques Chirac, and short ones: Mitterrand, Nicolas Sarkozy, Hollande). It's perhaps not surprising that Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the man many tipped to become France's second Socialist president, appears to have behaved in such a high-handed way in his private life: the sense of entitlement seems to have been entrenched.

Winock, who, incidentally, is good on Mitterrand's fierce attachment to his region of Charente and on his strongly Catholic upbringing, concludes that his subject was a master of the political arts but doubts that he was a great statesman. Hazareesingh’s verdict, meanwhile, is unequivocal: “He was the absolute narcissist, always late for meetings because of his ultimate contempt for others, and his belief that the world was there to serve his interests”. He concludes, “Mitterrand destroyed the soul of the French socialist movement, and it is still struggling to recover from his toxic legacy”. It rather sounds from that as though François II has inherited a poisoned chalice.

March 5, 2015

An evening at the Type Archive

By CATHARINE MORRIS

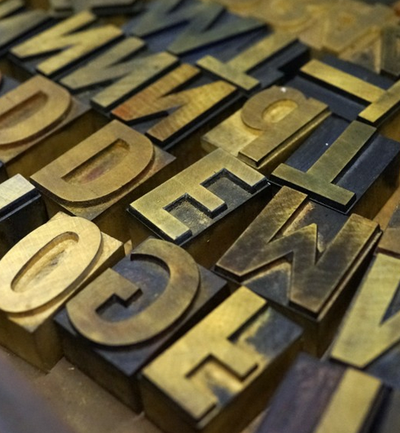

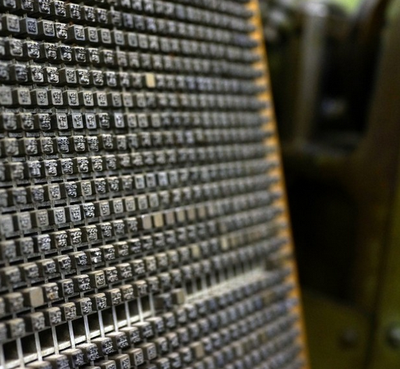

How exactly were books – and the TLS, for that matter – printed before computers? Those curious to know the answer will find it at the Type Archive in Stockwell, London SW9. If they can get in, that is: the archive – the largest in Britain, containing three major typefounding collections (those of Stephenson Blake, the Monotype Corporation and Robert DeLittle) – moved into its attractive cobbled premises at 100 Hackford Road some twenty years ago, but it was only last week that it opened its doors to a crowd of visitors for the first time. We were there for two reasons: to celebrate the publication of the History of the Monotype Corporation by Judy Slinn, Sebastian Carter and Richard Southall; and to commemorate the 500th anniversary (mentioned here before) of the death of the great publisher Aldus Manutius.

The chairman of the Archive’s trustees, Nicolas Barker, took to what I think were library steps to address us on the subject of Aldus, whom he described as “the man who made the printed book what it is today”: “It all starts, as far as I’m concerned, in 1948, when I went to visit Will Carter [the founder of the Rampant Lions Press], with my first feeble attempts at typesetting. He took one shuddering look at them and said, ‘What you need is a decent font of sixteen-point Bembo’. I bought it and I have used no other. It’s everybody’s favourite type, the easiest thing to get anything right with".

It’s called Bembo, Barker told us, because it was based on a type cut in 1495 at Aldus’s behest and used for a text written by Pietro Bembo (an account of his expedition to Mount Etna); "and it has such perfection of form – it is the best and most universal of all Roman type letters – that it has been the basis of every one that’s followed”. Bembo's book was one of 150 Aldus published in his lifetime; among the others was a series of pocket books for which he commissioned a new kind of type: italic. “Nobody had seen an italic type before and everybody used to ask whose handwriting was it based on”, said Barker. “I can tell you – and I’ve said this in print and nobody has contradicted me yet – that it was based on the hand of Aldus Manutius himself.”

Next up the steps was the Archive’s founder, Sue Shaw, who said “we’ve never been daunted by anything here”. Just as well: from the History of the Monotype Corporation we learn that when the Archive was formed, the delivery of the materials took seven weeks, at a rate of two ten-ton lorries a day. Shaw told us a bit about the history of the buildings: at the end of the nineteenth century they were leased to the veterinary surgeons Prince & King, who came to specialize in the care of dogs and horses (there is still a hay room, complete with hay hooks). At times the buildings also housed small circus animals, including a baby zebra; and in 1912 they were home to two baby elephants, brought from India by the Daily Mirror as mascots for a charity – a footnote in the Archive’s history that explains its charming logo.

The Archive is not just an archive, in fact: it manufactures type matrices for letterpress printing (the moulds from which metal printing type is cast); and the trustees, who are not in their first youth, as Shaw put it, are taking measures to ensure that the skills involved are preserved for future generations. The Archive offers four-year apprenticeships, which have been taken up by Nick Gill and Ian Gabb with great success (Shaw described their achievements as “stupendously impressive”); and the trustees are now in a position, she said, to invite “volunteers and experts of all kinds to help on the web and in person”. She made clear that the Archive is not a museum; the hope is that guides can be trained and people shown selections of its 8 million artefacts by appointment in small groups.

There was plenty of time, before and after the speeches, wine and canapés, for us to inspect some of the artefacts ourselves. We could even observe some of the equipment being used: one of the youngest printers at the event told us – while printing beautiful type samplers – that she enjoys the constraints of traditional printing, and finds that they often result in simpler, more effective designs than digital methods would. (She also said that it’s surprisingly easy, and inadvisable, to press stray tools along with the paper.) Among my fellow wanderers, fortunately for us, was Richard Small; he took the photographs that accompany this post, and you will find many more on his blog.

A Commentary piece on Aldus Manutius, and a review of the History of the Monotype Corporation, will appear in future issues of the TLS.

March 3, 2015

Influential books of the 1970s

By MICHAEL CAINES

First, if you're reading this and you came along to the novel of ideas discussion last Saturday evening: thank you for joining us, and contributing to a not-that-far-off-full house. With any luck, LSE will be able to release a recorded version as a podcast, so for now, from the chairing point of view, I'll just say that it was a pleasure. (And that it was perhaps strange that we didn't talk more about science fiction – a subgenre of the novel of ideas rather than some distinct, parallel genre?)

Second . . .

Influential Books, continued. This penultimate instalment takes us through the 1970s, from Robert Nozick's libertarian hokum (it was welcomed more diplomatically by Bernard Williams, in the TLS in January 1975, as "strikingly intelligent") to The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (a book that promised to be "highly controversial" even when its existence was merely a rumour, according to the young Nicholas Anning, whose later journalistic work included investigating the Chechen mafia). How very male, economical and fiction-free this decade appears to be – and how neat it was of Christopher Hill to say in 1972, of a book published the previous year, something that would so perfectly suit the cover of the much later reissue pictured below . . . .

*

BOOKS OF THE 1970s

71. Daniel Bell: The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism

72. Isaiah Berlin: Russian Thinkers

73. Ronald Dworkin: Taking Rights Seriously

74. Clifford Geertz: The Interpretation of Cultures

75. Albert Hirschman: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

76. Leszek Kolakowski: Main Currents of Marxism (Glowne nurty marksizmu)

77. Hans Kueng: On Being a Christian (Christ Sein)

78. Robert Nozick: Anarchy, State and Utopia

79. John Rawls: A Theory of Justice

80. Gershom Scholem: The Messianic Idea in Judaism, and other essays on Jewish spirituality

81. Ernst Friedrich Schumacher: Small Is Beautiful

82. Tibor Scitovsky: The Joyless Economy

83. Quentin Skinner: The Foundations of Modern Political Thought

84. Alexander Solzhenitsyn: The Gulag Archipelago

85. Keith Thomas: Religion and the Decline of Magic

Happy birthday, Josephine Hart – 3

2007. Copyright Geraint Lewis/Writer Pictures

By PETER STOTHARD

Fourteen years after the impromptu performance of Kipling recalled in yesterday's blog post, I found myself at Josephine Hart’s Poetry Hour. Once again there was a small group of journalists, different ones but the same sort of folk, listening to the same story of the bitter "Baronite" whose son, instead of following him into ships and steel, had "muddled with books and pictures, an' china an' etchin's an' fans" and whose "rooms at college was beastly, more like a whore's than a man's".

We were in the British Library; and as well as the newspaper folk there was a big crowd of poetry-fanciers, gathered to hear a selection of Kipling's works, this time read by a professional, the film actor and once so familiar James Bond, Sir Roger Moore.

Sir Roger had been invited by Josephine, his friend. There was the excitement of expectation that night in 2004 and even the slightest sniff of old Bermuda in the air, in the blond, bare wood library walls and furniture, in the mixture of the raffish and respectable, rich and not-so-rich, Angelfish and older males -as well as in the person of 007.

A blond woman beside me at the bar ordered a Martini, "shaken not stirred". Money was meeting art with a joke. But there was a bit of apprehension too. How would the star and the poet get on? The British Library drinks supply had quickly proved unsatisfactory in the Martini department. When Sir Roger walked out on stage, he seemed stiffer than we like our celluloid heroes to be.

Josephine Hart began offering up this sort of occasion, this sort of surprise, in 1987. Whatever poem you have ever heard read before, and wherever you have heard it, never miss a chance to hear it again under her auspices. In a city where any night you can find a living poet and his or her own work, she gives the dead poets some society.

Amid all the debates about whether public readings are a good thing, and, if so, who should be the readers and, if there must be readers, how they should read, she has put her faith in the versatility of actors. She began at an art gallery in Cork Street, tried Shaftesbury Avenue theatres, and her spirit is now ensconced in St Pancras. A Josephine Hart evening follows no theory. Her sense of what works on her stages has allowed huge variation of style -and a constant supply of surprises.

Not even the most regular attender ever knows quite what will come next. One night Edward Fox, who holds the whole text of the Four Quartets in his head, incanted Eliot's words as a stream of mystic song, like metrical joss sticks. On the same night Dame Eileen Atkins read her Eliot from a book and persuaded like a philosopher, a Santayana on stage. Simon Callow has created countless brief lives for Hart in his own magic way - like the watcher at the beginning of Herbert Read's "My Company" in a celebration of First World War poets: "A man of mine / lies on the wire; / and he will rot / and first his lips / the worms will eat".

Bob Geldof has had his rock star's pick of early Yeats -"The silver apples of the moon, / The golden apples of the sun". That night there were fans in the Library, more musical than poetical, who stepped out into the square and hummed the Judy Collins version. When Geldof crouched forward in his chair beside fellow readers Sinead Cusack and Rupert Graves, his short sleeves were dragged almost to his elbows: "I have spread my dreams under your feet; / Tread softly because you tread on my dreams". The Boomtown Rat and campaigner for Africa luxuriated in the familiarity.

Just as some in the audience might have thought this was too "celeb", the mood changed again. Out came Cusack, the most classical and versatile of Hart's regular performers, with "The Circus Animals' Desertion": "Now that my ladder's gone, / I must lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart". Relevance to events outside the hall is not what much of the audience is seeking. But it is a secret pleasure of Hart's Poetry Hours when the Now grabs at the Then - the ideals of Africa at those of Ireland, the Asian Tsunami at Eliot's river gods.

The night for Yeats was only days before Live8. Geldof arrived in front of the Library's giant statue of Isaac Newton with what seemed like twin ice-creams in front of his mouth, microphones through which he was barking at distant obstacles to his plans. When he began "The Pity of Love", we knew we should resist linking the two: but, as he intoned the words, not so much more subtly than that Bermuda guide ("The pity beyond all telling / Is hid in the heart of love; / The folk who are buying and selling, / The clouds on their journey above"), many did connect them, however quietly.

How did Sir Roger Moore succeed with the dying shipowner and his yearning that his son, Dickie, he of those "sickest fancies", should sink a father's dead body in the South Seas? It would be fair to report that the film star came on stage to a quiet reception.

Roger Moore, 2009. JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP/Getty Images

In the audience there were many men as big in business as the ballad's hero, those who began by "patching and coaling on credit, and living the Lord knew how, / We started the Red Ox freighters -we've eight-and-thirty now".

There was a somewhat higher proportion of "Harrer and Trinity College" aesthetes, a charge laid subtly by Kipling against his cousin Stanley Baldwin. There were politicians of our own day: Hart’s husband is the Tory peer and key maker of Mrs Thatcher's Conservative Party, Lord Saatchi. And there were the ticket-buyers who had paid their money to see their 007 - but were somewhat hushed to see him in person.

Did even Mark Twain, with even his most admiring band of Angelfish, bring tears flowing so widely and so fast? I doubt it. Moore did not use any actor's accent, not the regional burr which the poet himself used to read his character parts. He used no grand gesture. He did not have Mark Twain's pipe - nor the 1990 Bermudan's preaching roll. He was stiff. He almost ladled the words, regularly, without fuss, with a minimum effort that was almost frightening -as well as fertile for tears.

"For the heart it shall go with the treasure -go down to the sea in ships. / I'm sick of the hired women. I'll kiss my girl on her lips! / I'll be content with my fountain. I'll drink from my own well, / And the wife of my youth shall charm me - an' the rest can go to Hell!" Every line was like taking a light blow from a boxer. And by the end there were bruises on many minds.

Till next year: Happy Birthday, Josephine.

March 2, 2015

Happy birthday, Josephine Hart – 2

2010. Copyright Paul Rogers/The Times

By PETER STOTHARD

Yesterday was Josephine Hart’s birthday, as I posted here last night.

Master of the minimalist novel, maestro of poetry in performance, immaculate in black and white Chanel, Josephine has never left the memories of those who knew and know her.

I remember her birthdate because it comes the day after mine. Yesterday I exchanged emails with others who I remembered. I recalled some extraordinary discussions and events – and also that a decade ago I had written about her Poetry Hours for the TLS even though no trace of that piece survived in my mind at all.

In the grey light of this morning, March 2, my piece turns out to have described two readings of a poem by Rudyard Kipling. The first was as a sideshow to an Anglo-US summit in Bermuda while I was a foreign correspondent a quarter of a century ago. The second was fourteen years later and by Sir Roger Moore, one of Josephine’s galaxy of poetry reading stars.

To begin at Easter 1990: the chance to chant out Kipling's "The Mary Gloster" was the highlight of the Bermudan guide's day. The island was full of visitors – journalists, diplomats, military tourists, all sources of tips and other profits.

In the wider world the Berlin Wall was well down. Saddam Hussein was well up. Margaret Thatcher, also on her way down though not yet knowing it, had just arrived for an Atlantic summit with George Bush the elder.

"I've paid for your sickest fancies; I've humoured your crackedest whim", the local tour leader declaimed to a desultory band of hangers-on. "Dick, it's your daddy, dying; you've got to listen to him!"

And so we journalists did listen. An impromptu performance of a poem, whatever the reason for it, was a break from impenetrable political briefs. There were helicopters in the unusually grey sky and flash-pasts by American and British fighter planes. Up on the Hamilton hill, the then President Bush had no choice but to endure his usual dose of "backbone stiffeners" from the Iron Lady. Down in Pitt's Bay Road, a foreign correspondent could forget for an hour the first follies of the New World Order – and be entertained.

The purpose of the guide's performance, it eventually became clear, was to re-enact for visitors a local tourist scene, famous in "Happy Island" Bermuda, in which the elderly Mark Twain used to read aloud at his holiday home from the works of his favourite poet.

Rudyard Kipling's ballad, "The Mary Gloster", in which a self-made shipping tycoon on his deathbed ("'Not the least of our merchant princes'. Dickie, that's me, your dad") confronts his spendthrift art-loving "Harrer and Trinity College" son, was a special favourite of Twain's. Our Summit poetry reader proclaimed the lines outside Twain's house in sonorous black-preacher style, with rolling waves of admiration for Kipling's hero, the helpless financial pioneer with his devastated hopes of passing on his passions to his heir.

The knowledge that only a mile or so away a weakening Mrs Thatcher was out to handbag "Gentleman George" added frisson to this portrayal of Sir Anthony Gloster, hardman, realist, chancer, a disappointed millionaire obsessed in his last hours only with being buried at sea on the same Macassar Straits coordinates as his wife.

"And they asked me how I did it; and I gave them the Scripture text, / 'You keep your light so shining a little in front o' the next!' / They copied all they could follow, but they couldn't copy my mind / And I left 'em sweating and stealing, a year and a half behind."

We could all imagine the British Prime Minister enjoying that. According to the guidebook, Twain had regularly reclined, white-serge suited on his hotel bed, and read this poem aloud to old male friends and the young female admirers whom he called "Angelfish". By the end ("Never seen death yet, Dickie? . . . Well, now is your time to learn!") there were said to have been open tears from the women and stern blinking from the men. It was all in that "drawling, resonant voice": the sound that Twain uniquely brought to American literature was lent at these times to the poet of Empire.

Among our own tour band of Pitt's Bay Road there was generous appreciation but no flowing tears that day. This was not one of those poetry readings, all too common, which make one cry out for escape. But it was not quite a pleasure either. To imitate one great writer reading the words of another is not a role for an amateur. Both the place and the time were appropriate enough for Kipling – a colonial island when one way of the world was passing into another. But our journalists' eyes were on impending newspaper deadlines for the latest thoughts about Europe without Communism and the Middle East without the Cold War.

Unlike Twain's early twentieth-century guests, we did not even get the whole poem, still less "the bare hotel room, its pine woodwork and pine furniture, the loose windows which rattled in the sea wind", all of which the guidebook described. While Twain's listeners had heard "once in a while a gust of asthmatic music from the spiritless orchestra downstairs" we had constant helicopters and staff cars. While Twain was said to have "hair which gleamed and glistened like frost in the light of gas jets", our jets were F 16s.

Yet a poetry reading still defeated the political "read-outs" for a place in this reporter's memory. I can still recall more of this poem on the troubles of success than the press conference on the same theme that eventually followed.

What the essay is (not)

"The Grub-Street Hermit"; illustration from The Book of Days by W. R. Chambers, c.1870

The second round of Notting Hill Editions' biennial Essay Prize is underway. A compelling discussion took place last week at King’s Place NW1 on the constitution and health of the genre. Michael Ignatieff, whose essay on Raphael Lemkin – the man who coined the term genocide – won in 2013, and the essayist, novelist and poet Phillip Lopate joined Adam Mars-Jones – Chair of Judges for this year’s prize – to tweak and elaborate on the opening gambit that (in the words of Mars-Jones) "writing an essay can be a way of taking an idea for a walk”.

But one man’s walk – and Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion and Leslie Jamison were nodded to only in passing – is another’s saunter, trot or stumble. (Incidentally, as Matthew Beaumont points out in his new book on nightwalking, the adjective “pedestrian” originally referred metaphorically to “prosaic or uninspired writing”, only taking on the more literal significance of travelling by foot in the 1740s.) One of the few points on which Ignatieff and Lopate were in step was that the essay is, perhaps above all (though only just so and with umpteen qualifications), a personal journey.

So the next question is concerned with the nature of the tour guide. For Ignatieff, the essayist is a steady, honest and moral being, responsible for delivering his ward from A to B; for Lopate, he can be one of many versions of the self. Doesn’t this amount to the donning and dropping of personae, and doesn’t that leave the door open to unreliable narrators? (Indeed, to return to Beaumont: historically, as a noun, “pedestrian” has carried a whiff of poverty, even moral corruption.) Ignatieff seemed shocked by the very suggestion. Lopate wryly recast his point: “there is a knob I can tune up or down” – but the result is always a true expression of self. So far so slippery.

Next comes the question of how he relates to us, and, indeed, who “us” is. Where Ignatieff envisaged a Woolfian “common reader”, Lopate saw no such a thing, but rather reading tribes – readers of essays, readers of fiction, readers of history, and so on. The thing about the essay, Ignatieff said, is that, for structural reasons, being neither academic nor journalistic, it doesn’t belong to any one school. The form emerged on Grub Street and is thus, by definition, extra-institutional. (Which doesn’t mean that there isn’t a place for it within the institutions . . . .)

The tone should be confiding but not confessional – “it shouldn’t be an opening up of the veins”. And yet some of the greatest essays (“greatest” being a hopelessly greasy term) are drenched in blood, guts and fury. Think of Nietzsche and Baldwin. The key is that their themes were universal; there was always a narrative arc, a journey of (self) discovery, steered from a position of earned perspective, or wisdom.

“Wisdom? Really? . . . Does that make essay-writing age specific?”, asked Mars-Jones. The question was left hanging, though one couldn’t help but feel the speakers had a vested interest in concluding one way rather than the other. Does wisdom preclude humour? Ignatieff suggested that there can be few things as funny as a person on his high horse. (An image for which I was grateful: I love the idea of a panel in which the ubiquitous black pleather sofas are replaced by ornate, oversized fairground horses.)

Should there be an element of surprise? Not necessarily, but the most successful essays are often those where the reader (and perhaps the writer, though that is more difficult to gauge honestly) doesn’t know quite what they’re walking towards until it smacks them in the face.

Indeed, the closer the panel looked at the genre the more futile the idea of pinning it down became, beyond the formal constraints laid out in Notting Hill Editions’ submission guidelines that the piece be “between 2,000 and 8,000 words” and that it aim to “communicate with a wide audience”.

After the discussion, Mars-Jones opened the floor to questions. "Can we stick to the definition of a question as a short sentence that ends on an interrogative point?", asked Ignatieff. It turns out we couldn't even agree on that.

March 1, 2015

Happy birthday, Josephine Hart – 1

Josephine Hart1: 2009.Copyright Graham Jepson/Writer Pictures

By PETER STOTHARD

Today is Josephine Hart's birthday. I am not going to say 'it would have been' although 'was Josephine Hart's birthday' will forever be a true statement about the first day of March.

Josephine was and is the author of the novel, Damage. During her lifetime, cut short by cancer in the summer of 2011, she was also the most devoted and inventive poetry promoter of her age. She remains the presiding spirit of those readings, the greatest lines spoken by the greatest actors, that still bear her name.

If I were as efficient as Josephine always was, I would add pictures and links, including the link to the first piece that I wrote about the Poetry Hours in the TLS, to many other pieces and to the future plans in her memory.

Maybe tomorrow.

In the meantime, Happy Birthday to Josephine.

Today is Josephine Hart's birthday. I am not going to...

Today is Josephine Hart's birthday. I am not going to say 'it would have been' although 'was Josephine Hart's birthday' will forever be a true statement about the first day of March.

Josephine was and is the author of the novel, Damage. During her lifetime, cut short by cancer in the summer of 2011, she was also the most devoted and inventive poetry promoter of her age. She remains the presiding spirit of those readings, the greatest lines by the greatest actors, that still bear her name.

If I were as efficient as Josephine always was, I would add pictures and links, including the link to the first piece that I wrote about the Poetry Hours in the TLS, to many other pieces and to the future plans in her memory.

Maybe tomorrow.

In the meantime, Happy Birthday to Josephine.

February 27, 2015

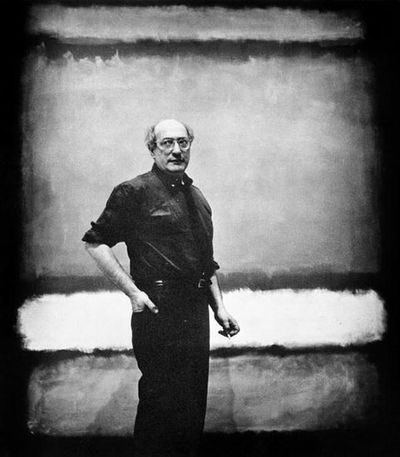

Mark Rothko, the mensch

Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas

Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

A place I’ve been hoping to visit for a while is the Mark Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Like the wonderful Rothko room in the Tate Modern, I imagine it to be meditative, transcendental but, despite its misleading name, not religious – all the things you always find in Rothko’s work. Inside the octagonal Chapel are, apparently, fourteen of his “black” paintings, variants on those engrossing dark hues with textural effects. He was commissioned to create this radical site-specific work and structure (he had a hand in the building’s design) in 1964. Yet he never got to see it: the Chapel was completed in 1971, a year after his suicide . . . .

“He’s the master of conceptual art”, Annie Cohen-Solal (whose new biography, Mark Rothko: Toward the light in the chapel will be reviewed in the TLS soon) said, in a discussion about the artist with Andrew Renton (the director of Marlborough Contemporary) on Sunday, at the start of this year’s Jewish Book Week. “He wants you to stop, sit and interact with his work; it’s never something to pass by.” As with Rembrandt’s experiments with light that put his work in advance of the art of his time, Rothko’s experiments with viewer experience do the same – Cohen-Solal argued – even down to his scientific research into pigments to achieve incandescent tones.

"Orange, Red, Yellow", 1961 © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

"Orange, Red, Yellow", 1961 © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

Mark Rothko, 1961 © Kate Rothko/Apic/Getty Images

Mark Rothko, 1961 © Kate Rothko/Apic/Getty Images

In his short book The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of art, written around 1940 and published in 2006 soon after the manuscript was discovered in storage, Rothko describes art as “not only a form of action, but also a form of social action and type of communication capable of producing effects on the environment just as any other form of action does”. This attitude, Cohen-Solal told us, was also pioneered by the curator Bryan Robertson. He put on the first British show of Rothko’s work at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1961, and was influential in his consideration about display spaces: softer lighting and off-white walls, for example, which, he realized, had important implications for his idea of art as an active experience, rather than passive consumption.

Indeed, the Tate’s permanent Rothko room is the result of the artist donating nine of his paintings to the gallery, along with exacting instructions on how they must be displayed – in “gloom”. (These paintings, in fact, were originally a reluctantly received commission from the Seagram restaurant at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York. “I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room”, Rothko claimed, before deciding to hold on to the paintings and return his fee.)

Born to Jewish parents in west Russia, Rothko and his family were forced to emigrate to America during the pogroms at the turn of the twentieth century, as were so many Jews who would become prominent artists and writers. With Ilya Bolotowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, Louis Schanker and Joseph Solman, among others, Rothko formed a group of Jewish artists in 1930s New York called “The Ten”. “Is there such a thing as ‘Jewish’ art?” Renton asked. “No”, Cohen-Solal replied, defiantly, “there’s no shared aesthetic; they all painted very differently. But there was a search for identity that’s symptomatic of being Jewish.” Art provided (does it still, I wonder?) an accessible space for expressing social, geographical and cultural turmoil, then.

There’s certainly an inward-turning beauty to Rothko’s work, I think, that lingers, so pungent and sumptuous; and it’s not necessarily all to do with his physical deterioration (after a heart attack) and consequent depression in the last two years of his life. In 1943 – some say a pivotal year for American artists moving towards abstraction – Rothko and Gottlieb wrote an open letter to the New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell: “There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and that only subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless”. It's this vision, most powerfully encapsulated in the timeless darkness of the Chapel – the Rothko admirers in the room agreed – that calls for a pilgrimage to Houston.

February 26, 2015

A novel of Baghdad

US soldiers from the 2nd Battalion the 12th Cavalry come under fire in a street in the Ghazaliya district of Baghdad. Jan 2007. Picture By Richard Mills/The Times

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

For anyone wanting to get a sense of what life might be like in modern-day Baghdad, I can wholeheartedly recommend Sinan Antoon’s novel The Corpse Washer (Margellos/Yale). The book was first published in Arabic (Beirut) in 2010 and is now available in an excellent translation by the author himself.

I say “excellent” but I’m not really in a position to judge, not being able to read Arabic. But I do know that it reads very well in the English version and that the four judges of the annual Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize deemed it the best translation from Arabic for 2014. (The translator/author picks up a cheque for £3,000.)

The novel covers the period from 1980, i.e. the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq war to the recent past: the last years of Saddam's tyranny, the disastrous American occupation and the sectarian violence that followed. All of these cataclysmic events are seen through the eyes of the artistically talented Jawad, whose life becomes ever more constricted by circumstances.

Antoon, who left Iraq in 1991 and teaches at New York University, was present at lovely Europe House in Central London yesterday evening to receive his award and give a short reading from the novel. In a spirit of inclusiveness Europe House now plays host to the Arabic prize and the biennial Hebrew prize (not given out this year). Also garlanded were translators from French, German, Italian and Spanish.

It is of course highly unusual for a writer to translate himself into another language: Nabokov did it, as did Samuel Beckett. Who else? In her introduction yesterday evening, Paula Johnson of the Society of Authors pointed out that this was only the second instance in the prizes’ forty-year existence of a self-translated winner (the first was the Anglo-German Michael Hamburger). As Antoon quipped, “I should have thanked myself”.

I’ve recommended Antoon’s novel, but don’t take it from me, heed those who know: in the words of Al-Ahram Weekly (Cairo), “Antoon is fast becoming not only the voice of the disaffections of modern Iraq, but also one of the most acclaimed authors of the Arab world”. Al-Hayat (London), meanwhile, wrote “This is the Iraqi novel par excellence . . . . This is the best novel about the Iraqi tragedy”. And if that’s not enough, how about this from al-Akhbar (Beirut): “With his second novel Antoon has emerged as the chronicler of the Iraqi nightmare”. For the judges, the novel is “heart-warming and horrifying, sad and sensuous, in equal measure”. They contend that “Antoon comes close . . . to the ideal in literary translation – the invisibility of the translator”.

The other translators receiving awards were: the late Patrick Creagh winning the John Florio Prize for his version of the Sardinian writer Marcello Fois’s visceral novel Memory of the Abyss (MacLehose Press); the American poet Rachel Galvin picking up the Scott Moncrieff for her excellent dual-language versions of Raymond Queneau’s collection of poems Hitting the Streets (Carcanet); Jamie Bulloch the Schlegel-Tieck for his version of Birgit Vanderbeke's brilliant novella The Mussel Feast (Peirene Press); Nick Caistor the Premio Valle Inclán for a highly readable translation of Eduardo Mendoza’s An Englishman in Madrid (MacLehose again), a novel which, Caistor pointed out, created a stir when it was first published in Spain in 2010, on account of the novelist’s sometimes comic treatment of the Spanish Civil War.

Rounding off the evening, Philip Hensher gave a charming, personal talk on the theme of “Reading Translation” in the course of which he cast doubt on the notion of the translator’s invisibility and praised occasional eccentricities in translations: N. S. Thompson’s versions of Leonardo Sciascia and the (much-criticized) H. T. Lowe-Porter versions of Thomas Mann. But Hensher also pointed out that while it was good that Lowe-Porter’s versions appeared so soon after German publication (presumably he had in mind above all her translation of The Magic Mountain which came out a mere three years after the original door-stopper), it also meant that the field was closed to anyone who might have given more accurate renditions of Mann’s prose. But in a sense weren't the best translations those that were nearest in time to the original?

Above all, it was good to hear a novelist praising translators for the “miracle” they produce. It’s a thankless task at the best of times, after all.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers