Mark Rothko, the mensch

Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas

Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

A place I’ve been hoping to visit for a while is the Mark Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Like the wonderful Rothko room in the Tate Modern, I imagine it to be meditative, transcendental but, despite its misleading name, not religious – all the things you always find in Rothko’s work. Inside the octagonal Chapel are, apparently, fourteen of his “black” paintings, variants on those engrossing dark hues with textural effects. He was commissioned to create this radical site-specific work and structure (he had a hand in the building’s design) in 1964. Yet he never got to see it: the Chapel was completed in 1971, a year after his suicide . . . .

“He’s the master of conceptual art”, Annie Cohen-Solal (whose new biography, Mark Rothko: Toward the light in the chapel will be reviewed in the TLS soon) said, in a discussion about the artist with Andrew Renton (the director of Marlborough Contemporary) on Sunday, at the start of this year’s Jewish Book Week. “He wants you to stop, sit and interact with his work; it’s never something to pass by.” As with Rembrandt’s experiments with light that put his work in advance of the art of his time, Rothko’s experiments with viewer experience do the same – Cohen-Solal argued – even down to his scientific research into pigments to achieve incandescent tones.

"Orange, Red, Yellow", 1961 © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

"Orange, Red, Yellow", 1961 © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy

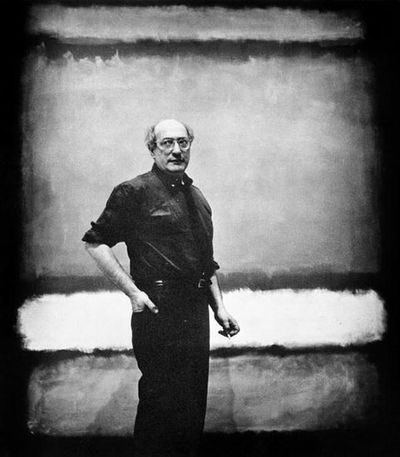

Mark Rothko, 1961 © Kate Rothko/Apic/Getty Images

Mark Rothko, 1961 © Kate Rothko/Apic/Getty Images

In his short book The Artist’s Reality: Philosophies of art, written around 1940 and published in 2006 soon after the manuscript was discovered in storage, Rothko describes art as “not only a form of action, but also a form of social action and type of communication capable of producing effects on the environment just as any other form of action does”. This attitude, Cohen-Solal told us, was also pioneered by the curator Bryan Robertson. He put on the first British show of Rothko’s work at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1961, and was influential in his consideration about display spaces: softer lighting and off-white walls, for example, which, he realized, had important implications for his idea of art as an active experience, rather than passive consumption.

Indeed, the Tate’s permanent Rothko room is the result of the artist donating nine of his paintings to the gallery, along with exacting instructions on how they must be displayed – in “gloom”. (These paintings, in fact, were originally a reluctantly received commission from the Seagram restaurant at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York. “I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room”, Rothko claimed, before deciding to hold on to the paintings and return his fee.)

Born to Jewish parents in west Russia, Rothko and his family were forced to emigrate to America during the pogroms at the turn of the twentieth century, as were so many Jews who would become prominent artists and writers. With Ilya Bolotowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, Louis Schanker and Joseph Solman, among others, Rothko formed a group of Jewish artists in 1930s New York called “The Ten”. “Is there such a thing as ‘Jewish’ art?” Renton asked. “No”, Cohen-Solal replied, defiantly, “there’s no shared aesthetic; they all painted very differently. But there was a search for identity that’s symptomatic of being Jewish.” Art provided (does it still, I wonder?) an accessible space for expressing social, geographical and cultural turmoil, then.

There’s certainly an inward-turning beauty to Rothko’s work, I think, that lingers, so pungent and sumptuous; and it’s not necessarily all to do with his physical deterioration (after a heart attack) and consequent depression in the last two years of his life. In 1943 – some say a pivotal year for American artists moving towards abstraction – Rothko and Gottlieb wrote an open letter to the New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell: “There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and that only subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless”. It's this vision, most powerfully encapsulated in the timeless darkness of the Chapel – the Rothko admirers in the room agreed – that calls for a pilgrimage to Houston.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers