Who was François Mitterrand?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

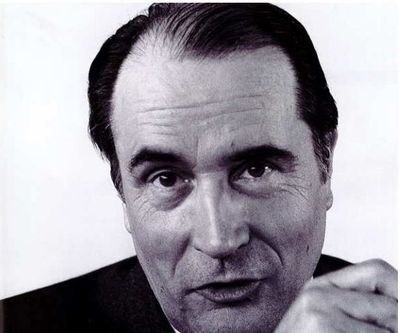

Was there a more mysterious, unfathomable politician in the Western world in the second half of the last century than François Mitterrand? Not for nothing was he known as the “Sphinx” (that enigmatic smile) or the “Florentine” (for his Machiavellian cunning). When he described Margaret Thatcher as having the “eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe”, he managed to combine sexual flattery with cold insult. What, I wonder, did la dame de fer make of the observation?

These thoughts were prompted by the arrival in the office this week of a new, amply illustrated biography by Michel Winock (423pp. Gallimard. €25) of France’s first Socialist president. The author has previously published well-received Lives of Clemenceau and Madame de Staël, while his Flaubert was favourably reviewed by Kate Rees in the TLS of May 31, 2013). As France’s second Socialist president struggles to make an impact in troubled times, Winock’s very readable book seems strangely pertinent. Or maybe it’s that the fascination with Mitterrand has never quite faded.

Reviewing a 600-page English biography of the man – yes, another one – by the BBC journalist Philip Short (subtitled “A study in ambiguity”; TLS, May 30, 2014), Sudhir Hazareesingh wrote “By the time [Mitterrand] retired in 1995, he had become the very symbol of institutional continuity and political longevity: his was the longest period of rule since the reigns of Napoleon III and Louis Philippe . . . . this first Socialist presidency marked the apogee of the republican monarchy in France – a delicious irony given that one of Mitterrand’s most captivating pamphlets . . . was Le Coup d’état permanent, in which he denounced the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the executive”.

That longevity spanned two seven-year terms as president, after two unsuccessful campaigns – in 1965 he polled 45 per cent, losing to de Gaulle, and in 1974 he managed 49 per cent against the lordly Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (he gained his revenge over Giscard seven years later). The presidential term has since been reduced to five years, to avoid the awkward periods of cohabitation between a president and a prime minister from opposing political parties – an awkwardness Mitterrand was adept at exploiting.

I didn’t know until I read Winock’s book that Mitterrand was endorsed without enthusiasm by the spokesman of the Left Jean-Paul Sartre (who died in 1980): “voting for Mitterrand . . . is a vote against a flight to the right by the Socialists. Many will vote for Mitterrand without illusions and without enthusiasm”.

But there were undoubted achievements: the abolition of the death penalty, the introduction of the minimum wage (le SMIC), further European integration, rapprochement with Germany (undermined by a later ambivalent response to the fall of the Berlin Wall). And then there were the big cultural projects: the installation of I. M. Pei’s Pyramide du Louvre, the new Bibliothèque nationale, the Opéra Bastille, etc. His first official outing as President was to the Centre Pompidou and later that year he attended the Arts Festival at Aix-en-Provence.

And he was, lest we forget, the most literary of presidents, a man of culture who would always read on plane journeys and counted Marguerite Duras among his friends (it is said that François Hollande doesn’t read). His first presidential investiture was attended by the novelists Yachar Kemal, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, Julio Cortázar, William Styron, Elie Wiesel (with whom he co-wrote a book) and Melina Mercouri among others.

Against all this has to be placed the fact that, in a move to split the Right, he introduced proportional representation, thereby giving Jean-Marie Le Pen's Front National a foot in the door. We can see the consequences of that today, alas.

Mitterrand’s reputation was dealt a severe blow by the publication in 1994 of Pierre Péan’s Une Jeunesse française, in which the author shed light on his wartime associations with Vichy – Mitterrand even accepted the Francisque, Vichy’s highest honour, an act that Winock says he later regretted. But, as is well known, Mitterrand went on to become active in the Resistance, and later saw no contradiction in this progression: after all, both Pétain’s Vichy and the Resistance were, in their differing ways, defending the nation. And to those who ended up on the wrong side, according to Winock, he showed unswerving loyalty, placing friendship above political expediency.

But this stubbornness was costly to his reputation: as Winock reminds us, the President would annually place a wreath on Pétain’s grave, and maintained a friendship with René Bousquet, the man who oversaw the Vel d’Hiv round-up in 1942. Winock quotes Pierre Moscovici, until recently finance minister in Hollande’s government: “as a Frenchman and as a Jew . . . what shocks me is that in 1994 Mitterrand admits to having kept in touch with René Bousquet up until 1986”. (Bousquet was assassinated in 1993, before he could stand trial for crimes against humanity.)

Then there was the fact that he kept his medical history secret from the public, having been diagnosed with prostate cancer not long after he became President. And of course the revelation of the second family (maintained at taxpayers' expense), when Paris-Match published photos of the president with his daughter Mazarine Pingeot in 1994. He was a seducer in the tradition of French heads of state, in spite of his relative lack of height (Winock puts it at 1m 70 – there is a thesis to be written on tall post-war French presidents, such as de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, Giscard, Jacques Chirac, and short ones: Mitterrand, Nicolas Sarkozy, Hollande). It's perhaps not surprising that Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the man many tipped to become France's second Socialist president, appears to have behaved in such a high-handed way in his private life: the sense of entitlement seems to have been entrenched.

Winock, who, incidentally, is good on Mitterrand's fierce attachment to his region of Charente and on his strongly Catholic upbringing, concludes that his subject was a master of the political arts but doubts that he was a great statesman. Hazareesingh’s verdict, meanwhile, is unequivocal: “He was the absolute narcissist, always late for meetings because of his ultimate contempt for others, and his belief that the world was there to serve his interests”. He concludes, “Mitterrand destroyed the soul of the French socialist movement, and it is still struggling to recover from his toxic legacy”. It rather sounds from that as though François II has inherited a poisoned chalice.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers