Peter Stothard's Blog, page 23

July 3, 2015

Wonder in the modern world

By HILARY DAVIES

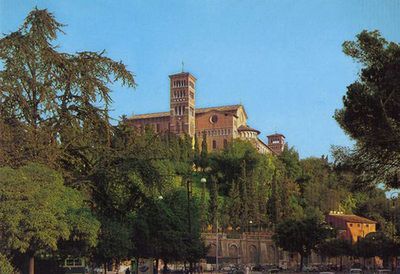

In mid-June poets, priests, monks, philosophers, teachers and theologians gathered in the cloisters of the monastery of Sant���Anselmo in Rome. Their purpose? To examine what place wonder has in the modern world, how it has manifested itself in the traditions which have shaped Europe and the Middle East, and how contemporary writers still bear witness to its power.

The conference ��� its full title being ���Thresholds of Wonder: Poetry, philosophy and theology in conversation��� ��� was organized under the aegis of the Power of the Word project, based at Heythrop College, who, with the Institute of English Studies at University College London, inaugurated these meetings in London in 2011. The intention is to foster interdisciplinary dialogue between creative artists, scholars and thinkers. This year���s participants had come from Silesia, California, Argentina, Norway, Brazil, Bucharest, Tel Aviv, Galloway, London and all over Italy.

And their exchanges offered rich pickings indeed. In the first sessions alone there were choices to be made between attending papers on Rilke, G. M. Hopkins and David Constantine; G. K. Chesterton, Peter Levi and Thomas Mann; the concept of enchantment in modernism and wonder in natural theology.

In the keynote address, Paul Murray, of the Angelicum (Pontifical University of St Thomas Aquinas in Rome) addressed one of the most important questions of the conference: why is it that, after centuries of co-existence and co-operation, theology and the arts have become estranged in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century? Aquinas on Aristotle compares philosophers with poets because both are concerned with wonder; Murray cited the famous incident in which the young Da Vinci was overcome with ���fear and desire��� as he looked into the darkness of a great cavern; and John Paul II���s Letter to Artists, in 1999, in which the Pope reminded them that living faith, and its expression in artistic works, has traditionally been a response to wonder at the divine presence. Murray went on to give a tour de force of arguments which have been used, both against and for, the engagement of artists with theology. He concluded with some recent instances: Randall Jarrell���s splendid remark, ���a poet is one who stands outside in a storm, hoping to be struck by lightning���; Mandelstam���s assertion that Christianity had ���released us into freedom���; and Seamus Heaney���s version of the birdman���s journey through wonder in ���Sweeney Astray���.

Sara Maitland, a novelist, independent theologian and the author of A Book of Silence (2008), was in combative mood in her plenary, which analysed the poetry of John Burnside, Kathleen Jamie, Alice Oswald and Jen Hadfield in terms of the emergence of ���the secular sacred��� in poets who cannot, or will not, subscribe to organized religion. Rather, they have turned to our experience of landscape as the bearer of the necessary myth of the tribe, ���the ecology of relationships between self and other, past and present, the living and the dead���. How this relates to a different view of nature as inhabited by the ���grandeur of God��� is, of course, a vexed matter, on which there was lively debate.

Caravaggio ���The Conversion of St. Paul���, 1600-01

Jon Sweeney introduced a refreshing look at St. Francis of Assisi���s ���Canticle of the Creatures���, analyzing how the saint uses the senses, with the notable exception of taste, to revivify the doctrine of revelation through creation; in so doing Sweeney was seeking to re-appropriate the work for a theology of wonder, rather than reading it merely as a proto-ecologist text.

On the final day, Ben Quash, Professor of Christianity and the Arts at King���s College, London, presented an examination of the visual arts: what of the invisible, of awe and wonder, can be conveyed by concrete depiction in art, from Gothic to Baroque, from Caravaggio���s ���Conversion of St. Paul��� to Le Corbusier���s chapel at Haut-Ronchamp? To reflect on how the plastic arts seek to evoke the ���ineffable���, as it is experienced in the word, was an excellent illustration of how wonder has engaged, and will always continue to engage, man���s imagination. What better setting than this quiet Roman borough ��� all snaking, sun-bathed lanes and lazily echoing bells ��� to explore such matters at length . . .

Le Corbusier���s chapel at Haut-Ronchamp

July 2, 2015

Richard Aldington's test for novelists

By MICHAEL CAINES

July 2, 1938 saw the writer Richard Aldington puzzling over a question. Was there such a thing, he asked in a TLS essay called "Knowledge and the Novelist", as "novelist's knowledge" about life? Could it be distinguished from the special knowledge of "the historian, the biographer, the good journalist, the old woman at the fireside and the village liar"?

Aldington, himself a novelist, couldn't be sure that there was any such thing. To his mind, "any intelligent Fleet Street journalist" knew more about "what goes on in the world" (which is what he meant when he talked about "knowledge of life") than the "most up-stage novelist".

And, with this suspicion in mind, he revealed how he had amused himself by devising something utterly sadistic: a "general knowledge paper for novelists", which you can now try for yourself . . . .

Warning: although they would seem to invite a modicum of realism, answering these questions might best be attempted in an absurdist frame of mind:

Describe the training of a metropolitan policeman and give your ideas of what he does with his leisure when (a) unmarried, (b) married.

How does an East End greengrocer run his business?

What are the duties of a barrister's clerk?

Describe a typical day in the lives of (a) a racehorse trainer, (b) a jockey, (c) a stable-boy.

What are the functions of the Lord Chancellor?

What do you know about the industries of (a) Middlesbrough, (b) the Clyde, (c) Manchester, (d) Slough?

Suppose you had to take over the organization of Lyons Corner House, how would you set about it?

Describe accurately the thoughts and actions of (a) the commander of a torpedo boat going into action, (b) an engineer ordered to construct a reservoir in North Wales, (c) a London stockbroker on hearing of another Wall Street crash.

Well? How did you score . . . ?

"No wonder most novelists prefer to write about love", Aldington concluded, convinced that the world beyond ourselves is not ��� but perhaps ought to be ��� the stuff of fiction. (I prefer to imagine that there could be more pleasure to be had from the imagined, improbable, even ridiculous story of, say, a stable-boy feeding the Lord Chancellor carrots in a Lyons Corner House, than from a 100%-correct exam paper.)

Nonsense aside: Aldington could be a rather grumpy and stern critic when confronted by one of his bugbears, notoriously doing for the Georgian poets with this stabbing line: "They took a little trip for a little weekend to a little cottage where they wrote a little poem on a little theme". His bitterness got into his novels, too, where he could quite poisonously portray acquaintances such as T. S. Eliot and D. H. Lawrence. There was more to him than bitterness, however, as I've found reading his many, often generous and carefully considered TLS reviews.

His point here seems to be that the novelist has no "special intuition" about "human nature" that can be separated from the knowledge anybody else might have of it. This is his down-to-earth view of fiction, and a reaction against what he sees as the "fulsome talk" of the Romantics about art. "Cutting out novels about animals, utopians and detectives, you might say that the novelist . . . tries to impart a special knowledge about human nature. But there he bumps up against the psychologist . . . ."

Others were not convinced: "Utterly beside the point to ask a novelist how an East End greengrocer runs his shop", ran a letter that appeared the following week. "The novelist neither knows nor needs to know. His business [always his . . . ?] is with the effect upon the human mind and spirit of running such a business in such conditions." And wasn't he confusing journalistic description with novelistic imagination?

Ignoring the first point, Aldington replied in a jovial mood about the second: "Are you not as staggered and grieved as I am by [the] implication that journalists have no imagination and no gift of creation? . . . I am told that most successful practitioners in that line are such pure artists that they refuse to contaminate the imagination by actually witnessing the event. They are generally Scots who remain cloistered in some convenient tavern, far from the vulgar reality . . . ."

It would be vulgarly unimaginative, I suppose, to suspect that a change of tone and outlook took place between Aldington's "Knowledge and the Novelist" and his letter because of events in his personal life: his divorce from his long-separated wife, the poet H. D., had gone through, he got married again (this time to Netta, also divorced; "It's rather like a movie", he wrote of the whole, rather messy situation), and his daughter Catherine was born on July 6.

As it happens, this was one of Aldington's last pieces for the paper, for which he had written since 1919; he emigrated to the United States a few years later. And although he had already suggested almost a decade earlier that he could "do better than endless (quite skilled) translations and T.L.S. reviewing", it was only now that he moved on ��� or felt he was being moved on.

For on this day, July 2, 1938, as others were trying to answer his little quiz, he noted, in a letter to a friend, that the way the piece was published, as "a signed article with a photograph" seemed significant: "Evidently they don't wish to commit themselves too far". He wrote one last essay review, later in the year ("literature is liable to obsolescence"), and one last review ��� and that was that.

June 30, 2015

Short stories and other units of distraction

By ANDREW IRWIN

Does the short story have a bright commercial future? Maybe not ����� but let���s enjoy it anyway. That seemed to be the message to take home from the recent London Short Story Festival. Only in its second year, the festival is growing, with sixty-five writers involved and dozens of events to attend. The organization of, and transition between, these events was broadly slick but had just enough hiccups (microphones that just wouldn���t stay on; the shrill hiss of feedback from the speakers; passing vehicles that prevented the panel���s audibility for decent stretches at a time), to make the whole thing seem likeable.

Salt used the festival���s first event to publicize its latest anthology, Best British Short Stories 2015. The authors of three stories, selected for the volume, K. J. Orr, Alison Moore and Helen Simpson, read extracts from their work, giving the listener faith that the form has merits beyond brevity. Character portraits are often sharp, passing details become charged with signification, and each line has to work hard, compressing action and exposition.

Simpson���s story, ���Strong man���, about a woman waiting for, and then chatting to, a Russian refrigerator repairman, was particularly evocative. The story lasts only a few pages, but, as the discussion turns to the Russian President and the narrator���s thoughts turn to her own past, personal and political histories subtly intertwine.

Listening to stories, despite the nostalgic bed-time implications, is probably not the best way of experiencing them ��� especially in a crowded room. Too many variables are introduced ��� whether the speaker is charismatic, whether the room is noisy, whether your mind wanders for a second and you lose the thread. But the Salt event nicely laid out the tenor of an anthology that sounds well-worth reading.

Nikesh Shukla, who was chairing the event, began by jocularly encouraging the audience, in a distinctly Husserlian mode, to bracket the world. Instead of hand-wringing about the commercial viability of short stories, we should instead assume that they do matter and move on from there. The stance works well enough for a single talk, but, from a broader perspective, it���s impossible not to suspect that the market for short stories will remain a niche. Clearly people are keen to write short fiction (when the writers in the room were asked to raise a hand, at one point, about three-quarters of the audience did so), but wouldn���t they be better advised to turn their attention to the more sellable novel?

Comma Press is seeking to change the way that we consume short fiction with the launch today of its new digital platform, MacGuffin. Jim Hinks was at the Short Story Gatekeepers event to explain what this entails. The idea seems to be twofold ��� first, to provide a space for writers to self-publish their work (poetry, as well as fiction), and second, crucially, to increase the overall size of the reading market. All stories on MacGuffin appear both in print and audio versions, designed to appeal to commuters, who look for discrete and downloadable units of distraction.

The result, if MacGuffin succeeds, will be a democratic approach to writing, with direct routes from author to reader, without the need for a publisher in between.

This is obviously no new idea ��� as long as there���s been the internet, there���s been self-publishing. But, as the clich�� goes, Apple didn���t invent the Mp3 player ��� it just made it inviting.

Not everyone will think that the democratization of writing is a good thing, however. The result seems likely to be a market flooded with noise. As David Foster Wallace said (in David Lipsky���s Although Of course You End Up Becoming Yourself), ���there are 4 trillion bits coming at you [online], 99 percent of them are shit and it���s too much work to do triage to decide���. It���s not clear that more bits is preferable to fewer. Still, if MacGuffin succeeds in increasing interest in fiction, and particularly in short fiction, it will be an admirable feat.

One of the platform���s most distinctive features is the presence of open-analytics ��� allowing anyone to see how a story is being read, including how far readers get before giving up. It���s a daunting piece of information. But Jim Hinks had some words of comfort: while the site is in beta, they���ve been testing these tools out on a number of the greats, now out of copyright. It seems that James Joyce doesn���t fare too well when it comes to drop-out rates.

June 29, 2015

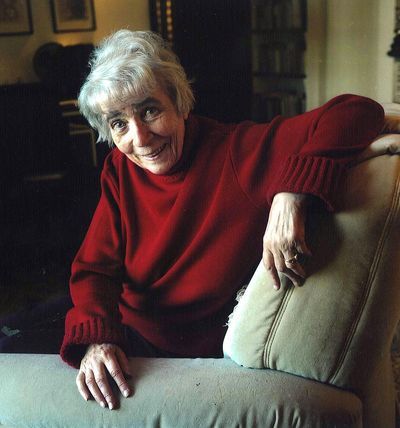

A word about Christine Brooke-Rose

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Ah but airports have frontiers. And travel-talk ensues with Herr Helmut von Irgendetwas who travels in textiles as others travel in simultaneous interpretation. . . . You will find your life-jacket under your seat. This life-jacket can serve on an unconscious person. Uw zwemvest bevindt zich onder uw stoel. Dit zwemvest kan dienen voor een bewustesloos persoon. Questo salvagente one day will have no frontiers and no passports per assistere anche una persona priva de conoscenza . . . ."

There is much "travel-talk" in Christine Brooke-Rose's Between (1968), living up to the sense of transit implicit in that one-word title. The novel flits across language "frontiers", as in the passage quoted above, out-paces punctuation, while also bridging the supposed gap between comic wordplay and serious purposes: "good jokes", the anonymous TLS reviewer wrote, "become epitaphs for irrecoverable experiences". "Oh yes and travel-talk ensues half drowned in air-conditioning and other circumstantial emptiness . . . ."

It's for the sake of works such as Between ��� and the computer-voiced Xorandor, the typographically liberated Thru ("The bour-geois i-dyll is o-o-o-ver"), and the rest ��� that a Christine-Brooke Rose Society was launched in Oxford last week, at the author's old college, Somerville. That event, in turn, is one source of inspiration for this: the third instalment in an (unintended) trilogy, after Brigid Brophy (who also set a linguistically experimental fiction, In Transit, in transit) and B. S. Johnson, of notes on mid-century writers. This time in podcast form.

My thanks to one of the new Society's founders, Natalie Ferris, for joining us to talk so insightfully about Brooke-Rose's life and work. (And if you won't take her word for it, or mine, that these are experiments well worth revisiting, perhaps you'll consider taking Ali Smith's. . . .)

June 25, 2015

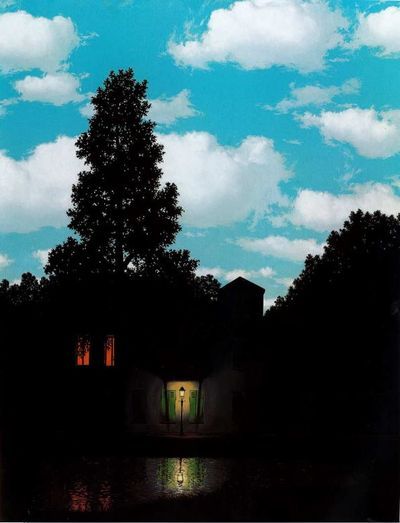

Two Magrittes

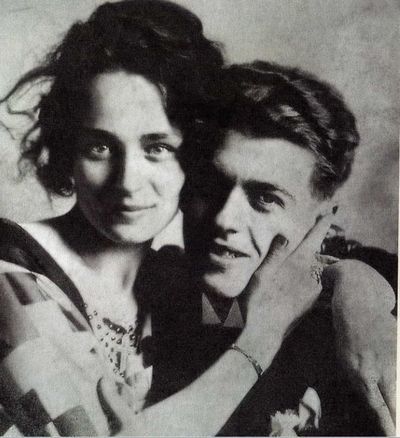

Georgette and Ren�� Magritte on their wedding day, June 22, 1922

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The Ren�� Magritte Museum in the Jette suburb of Brussels should not be confused with the Magritte Museum in the city centre. This famously playful artist would surely have appreciated the potential for confusion this near-doubling up offers. The first was opened in 1994, the second only in 2009. Magritte might also have been tickled by the fact that the second museum forms a part of the Mus��es Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique ��� he flunked out of the Acad��mie Royale des Beaux-Arts when a student.

After some years moving in Brussels' Surrealist circles in the 1920s (he was born in 1898), Magritte and his wife Georgette moved to Paris where they stayed for three years. Although he fraternized with the French Surrealists, it was characteristic that Magritte should have elected to keep his distance from them ��� setting up home in a villa in Perreux-sur-Marne to the east of the city. This conventional m��nage earned the scorn of French Surrealism���s bully boy Andr�� Breton. When, one evening, he expressed surprise at seeing Georgette wear a cross on a gold chain around her neck, and suggested it should be thrown away or replaced by a piece of wood, it was the final straw. Georgette is said to have stormed out of the room followed by an equally furious Ren��. (It���s worth noting that Ren�� himself was rarely, if ever, photographed out of a jacket and tie, but that doesn���t make him any less of an original or remarkable artist.)

The couple returned to Brussels in 1930 and rented an apartment at 135 Rue Esseghem in the tranquil suburb of Jette (it now sits under a flight path). They lived there from 1930 to 1954, during which time the artist sold little, and yet produced some 800 works (half his output). In 1954, at Georgette���s request, the couple moved into a bigger apartment in the town of Schaerbeek outside Brussels, where they remained until Rene���s death in 1967.

The ground floor of the house in Jette has been restored to as near a resemblance to its appearance in Magritte���s time as possible. Visitors peer into the rooms over a glass partition door. The upper three floors (which we are required to don shoe covers to access) were separately occupied when Ren�� and Georgette lived in the building. The downstairs rooms convey an atmosphere of slightly bizarre cosiness; the sky blue wall paint in the sitting room seems rather Magrittean, as does the bright red wardrobe. And there���s one of the couple���s Pomeranians, stuffed and positioned on the bed (they had no children but six dogs of that breed). In the small dining room/studio Magritte worked and met his Surrealist friends, with whom he also larked about in the garden ��� much of it captured on Magritte���s Super-8 films, which can be seen in the main museum. The house was, effectively, the headquarters of Belgian Surrealism for two decades.

In the garden meanwhile is the studio which Magritte built himself and where he did much of his commercial work, such as graphics and posters, including for the Belgian national carrier Sabena; he called the space ���Dongo���, after the main character in Stendhal���s novel The Charterhouse of Parma, Fabrizio del Dongo.

The upper floors of the house contain an extensive collection of Magritte���s drawings, lithographs and the odd painting. It���s all well worth seeing, and when I went I was the only visitor until the doorbell heralded a party of eight whose arrival sent the staff of four into a vague panic.

As for the Mus��e in the city centre, arranged on three floors it houses the most extensive collection of Magritte���s work anywhere in the world, including of course that most mysterious and unsettling work, "The Empire of Lights" (1954, above, detail). How gratifying it was to see there Brussels primary schoolchildren being introduced to this beguiling and unfathomable artist. I wonder what they made of him.

June 24, 2015

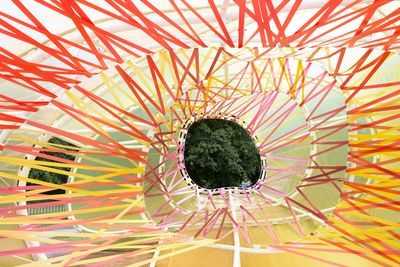

The Serpentine's pi��ata pavilion

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Temporary architecture was a rare and radical thing when the Serpentine Gallery started their summer pavilion project fifteen years ago. The prototype pavilion in 2000 was designed by Zaha Hadid, who, back then, was little more than a ���paper architect��� (barely any of her designs had been built); and many international heavyweights of the architectural (and occasionally art) world have been invited to create one every year since, including Daniel Libeskind, Oscar Niemeyer, ��lvaro Siza, Frank Gehry, Olafur Eliasson, Ai Weiwei and Herzog & de Meuron, as well as lesser-known names in the past couple of years.

Each pavilion takes six months from design to completion, and ���costs the same as it would to put up a tent on the park���s lawn���, Julia Peyton-Jones, the co-director of the Serpentine Gallery, reminded us yesterday at the opening of this year���s structure, designed by the Spanish architects SelgasCano (Jos�� Selgas and Luc��a Cano; they���re also responsible for a recent polytunnel-type pop-up caf�� just off Brick Lane). ���We commission the pavilion architects in the same way we commission artists in the gallery���, Peyton-Jones added. ���We push them with almost impossible requirements.���

Entering this pavilion is like stepping into a psychedelic greenhouse, or inside the abdomen of a supernatural insect. Woven strips of bold-coloured, translucent plastic (red, yellow, green, orange) and opalescent panels, stretched between white steel poles, are overlaid, angled and curved, creating patterned shadows and beautiful, shifting hues. A meandering path runs around some of the structure���s perimeter, with openings that either look outwards, framing sections of the park, or nudge you inwards, into different parts of the pavilion. If a little too tropical when the sun blasts through the layers of plastic, it���s nonetheless a happy, vibrant space ��� imagine a Spanish street fiesta.

Selgas described it yesterday as a ���pi��ata��� of small homages to the past pavilions in this anniversary year, while at the same time being experimental and new. You can feel the lightness and crosshatched shapes of, say, Sou Fujimoto���s (2013) and Gehry���s (2008), the handmade quality of Smiljan Radi�����s last year, and the angles of Toyo Ito���s (2002). What���s also been important to Selgas (coordinated with his own structure in bright orange trousers and a forest-green shirt) and Cano (all in white) is that it���s an urban project. They were inspired by the democratic space of London���s Underground, in particular, the way people navigate around each other in the tunnelled walkways.

How we relate to and use the structure is fundamental. So is sustainability: the pavilion needs to be easily dismantled and moved once it���s sold on, and the money made goes towards next year���s. After all, the pavilion is a public, not-for-profit space that aims to engage with, and inspire, contemporary architecture. And the Park Nights events held in the pavilion over the summer ��� one evening, ���Dying on Stage���, will feature a dance choreographed by the artist Christodoulos Panayiotou; another has the composer Christian Wolff ���play��� the pavilion ��� seem like just the stuff to achieve this; I���m particularly intrigued to see how the latter is pulled off.

���Architecture is not about the finished object���, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Peyton-Jones's fellow Serpentine director, told us: ���it���s not a relic, it���s an evolving process: what will happen to the pavilion in the next three months while it���s up, and how will people respond to it���. Isn���t this the best way to understand architecture, rather than through drawings, photographs or films? I think so; and, going by the number of passers-by waiting to see inside as we reluctantly trickled out, I���m not the only one.

June 23, 2015

The novella umbrella

By MICHAEL CAINES

���Why is any story of more than fifty pages now called ���a short novel��� or ���novella������, Julian Symons asked, in a TLS review of 1957. ���Have publishers invented a new literary category?���

Not that the word itself was a novelty, as Symons well knew ��� it meant something to the authors of the fourteenth-century Decameron and the sixteenth-century Heptameron. Writing in the same year and the same paper, Michael Hamburger could note that ���German literature is extraordinarily rich in minor and major masterpieces in these forms��� ��� meaning ���small-scale works of fiction, the conte and the novella���. Wikipedia agrees, while defining the German form as:

���a fictional narrative of indeterminate length . . . restricted to a single, suspenseful event, situation, or conflict leading to an unexpected turning point (Wendepunkt), provoking a logical but surprising end; Novellen tend to contain a concrete symbol, which is the narrative���s steady point.���

Does that describe the modern novella, too?

Fortunately for those who prefer their fiction free-roaming rather than rule-bound, there is no single answer to this question. Writers of fiction, as ever, must do what they need to do ��� and readers (who may be critics or writers of fiction in turn) go bounding after them.

Hence the suggestion on Goodreads that a novella is ���more complicated than a short story��� but lacks chapter divisions, has a ���single effect��� and can often be read in a ���single sitting���. It cites the word count given by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Nebula Awards ��� 17,500 to 40,000 words ��� but acknowledges that there are higher and lower alternatives.

The organizers of this year���s inaugural Penny Dreadful novella prize, meanwhile, frankly admit that it���s ���difficult, nay, impossible to define what exactly constitutes a novella���: ���We say, however, it is prose between 15,000 and 35,000 words. There is no topic off limits and we enforce no style or genre���. That seems like a sensibly broad approach to me; although I can���t help wondering what kind of entries they would receive if the rules called for suspenseful stories of any length with a Wendepunkt, a concluding twist and a ���concrete symbol���.

Richard Ford, confronted with the problem of this ���worn-out literary term���, this all-sheltering generic umbrella, must have rolled his eyes. His introduction to the Granta Book of the American Long Story (for which there should be a few more European counterparts, perhaps) is called ���Why Not a Novella?���. For him, the term was too ill-defined to be useful. ���I have no conviction���, Ford wrote, despite the anthology���s title, ���that even length is an inspired standard for what these stories have in common. Length certainly doesn���t constitute a shaping purpose.��� (Making his own long stories fine examples of a non-genre.) ���Almost everything the word ���novella��� has meant over the centuries is not what it means in current writerly usage.���

Or in current commercial usage, you could say: one day somebody more tenacious than me will pursue the rise of the subtitle ���Stories and a novella��� and its variants. (See some distinguished examples by Ismail Kadare, Edmund White and Cynthia Ozick.) Isn���t this a publisher���s optimistic means of suggesting that some book that isn���t a novel is, nevertheless, excellent value for money? (And certainly not one of those pure, awfully difficult-to-shift short story collections one occasionally hears about.) Melville House, by contrast, blithely describe the novella as a "renegade art form", and offer an impressive but unhelpfully capacious series of "novellas" ranging from Aphra Behn's Oroonoko to The Dead by James Joyce (via those well-known renegades Henry James and Samuel Johnson).

As Brian Bouldrey puts it, in an insightful Sewanee Review essay on the subject, length is red herring here: ���[A. E.] Coppard wrote long short stories. [Muriel] Spark writes economical daggerlike novels. These are not novellas���. Ford, anxious to avoid creating further confusion, abstained. Bouldrey daringly suggests that some publishers don���t share this sense of a duty to clarity:

���given our short attention spans and the need to market books aggressively, the term is bandied about as a matter of convenience: what���s called a short novel today is actually a novella printed in an oversized font, and what���s actually a prolix short story is called a novella to fill out a book of stories���.

Writing in 1999, Bouldrey had a good idea, however, about what made novellas what they were: their density. Their prose, he suggests, is ���dark- and close-grained���. The single effect turns out to be that of a ���black hole���: ���what novellas cast into the universe tends to be drawn back again��� And he quotes Hortense Calisher, who must have considered the subject deeply in the course of her long writing life:

���The novella can take on any of the novel���s roles. It has but one departure ��� one that makes it unique. It is not merely a shorter novel, of less wordage than commonly. It is a small one, tenaciously complete. . . . Complexity rims the edges, but is there to be fended off.���

The narrative's length, then, might be thought of as the likely side effect of a particular artistic attitude, rather than its defining feature.

���An appreciation for quieter music is a developed, evolving thing���, Bouldrey remarks, ���Readers turn to novellas with the same cultivated maturity.��� No wonder, if that���s the case, that ���The term makes us uneasy���, as Lavinia Greenlaw once put it in the TLS; it suggests ���something a little rococo and overbred���. It is the domain of ���anomie, displacement, subtext and knowingness���, of ���exiles and Europhiles���: Henry James, Marguerite Duras, Mavis Gallant and Arthur Schnitzler.

That���s the distinctive form in which I hope ��� for the sake of those Penny Dreadful judges, apart from anything else ��� the novella continues to thrive.

With thanks to Jeannie Vanasco.

June 18, 2015

Wandering through Waterloo, pt 2

The Lion's Mound at Waterloo with the Rotunda to the left

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Anyone who feels Waterlooed out need read no further. Suffice to say that although the French are alleged to be avoiding the subject altogether, Le Monde today contains a special eight-page supplement, culminating in an interview with Napoleon���s most recent biographer Andrew Roberts, who believes Waterloo need never have been fought ��� ���Napoleon was no longer a threat to peace���. Roberts���s French rival biographer Patrice Gueniffey, meanwhile, writes in Le Figaro that Napoleon���s defeat marked the true end of the French Revolution. ���Waterloo was the first day of the nineteenth century, just as August 1 1914 was the first day of the twentieth century.���

With the anniversary in mind, I thought it would be fun to look again at Stendhal���s great novel The Charterhouse of Parma: early on in the book, Stendhal sends his picaresque hero the seventeen-year-old Fabrice/Fabrizio del Dongo, from Como in northern Italy to Paris, on a heroic quest: ���He had gone with the firm intention of meeting the Emperor [during the Hundred Days]. It never occurred to him that this might be difficult . . . . In Paris, every morning he went to the courtyard of the Tuileries palace to watch Napoleon taking the salute at the march-past; but he never managed to get close to the Emperor��� (my translation). Fabrice finds his way to Waterloo, attaches himself to a regiment and a sympathetic corporal takes him under his wing. He even acquires a horse, which he is promptly relieved of. Caught up in the French retreat, he witnesses the following exchange between the corporal and a wounded general:

���You���re to give me four men,��� he said to the corporal in an exhausted voice, ���to carry me to the ambulance. I���ve got a shattered leg.���

Go f*** yourself,��� replied the corporal, ���you and all the generals. You���ve all betrayed the Emperor today.���

As Fabrice spends two weeks recovering from a battle wound in an inn at Amiens, he wonders whether what he saw was really a battle and, if so, was it Waterloo? Stendhal���s brilliant depiction of the battle is generally reckoned to be accurate in its detail.

Walter Scott was the first ���celebrity��� to visit the battlefield (although people had begun arriving from Brussels the following day to survey the carnage). Having heard news of Wellington���s victory in Edinburgh on June 24, Scott set off with three friends the following month, taking in the fortress of Bergen-op-Zoom and the sights of Brussels on the way (where he noted with satisfaction the good impression the regiments of the Highland corps had made on the citizens). It was his first foreign trip and he followed it with an extended stay in Paris. The resulting, commissioned, account, Paul���s Letters to His Kinsfolk, which is full of fascinating detail, was published in January 1816. (I reviewed a new edition, Scott on Waterloo (Vintage) and which includes Scott���s epically dreadful poem ���The Field of Waterloo��� and an excellent introduction and notes by Paul O���Keeffe, in last week���s In Brief pages of the TLS).

Robert Kershaw���s 24 Hours at Waterloo (WH Allen) is an excellent compendium of ���Voices from the battlefield���, complete with timelines and maps, which makes for absorbing if grim reading. Kershaw, a former Para turned military historian, writes that ���even by the ghastly standards of the day, Waterloo was universally regarded as being extremely violent���. He has a nicely caustic tone: ���British soldiers shared Wellington���s somewhat jaundiced opinion of ���foreigners���. Soldiers, as they do, swiftly reduced them to stereotypes: brave but nervous Frenchmen, brave but clumsy Prussians, cowardly Belgians, inexperienced Dutchmen and of course brave, stoic and courageous Englishmen���.

Kershaw���s use of first-hand accounts brings the day to life: ������A storm, such as I had never seen the like of, suddenly unleashed itself on us and on the whole region���, wrote Lieutenant Jacques Martin, 45th Line Regiment, part of the leading French corps.��� Ensign Edmund Wheatley of the King���s German Legion wrote that ���a ball whizzed up in the air���; ���up we started simultaneously���. ���Glancing at his watch he saw ���it was just eleven o���clock, Sunday morning���. His sweetheart Eliza Brookes . . . would be ���just in church at Wallingford or at Abingdon������.

And the French made an impression on the enemy: Corporal John Dickson of the Scots Greys wrote ���The grandest sight was a regiment of cuirassiers dashing at full gallop over the brow of the hill opposite me, with the sun shining on their steel breastplates. It was a splendid show. Every now and then the sun lit up the whole country. No one who saw it could ever forget it���.

Kershaw tells us that, up to Waterloo, Napoleon had won all but ten of his seventy-two engagements, but they had taken their toll. ���Physically, Wellington was more vibrant than the increasingly flabby Napoleon��� (a temporary exhibition back at the Waterloo museum on the two leaders��� crossed destinies reminds us that they were both forty-six at the time, born within three months of each other in 1769). Soldiers of the Grande Arm��e noticed how much weight the Emperor had put on since his enforced stay on Elba.

Other nuggets include the fact that ���boots in 1815 were a single issue; there was no such thing as a right or left foot���; that local coalmines made muddy, storm-sodden conditions even worse (���Coal dust coated the local roads and produced a ���black mud mixed like ink������, according to Captain Duthilt, a veteran of the Revolutionary Wars); and that Marshal Ney, the ���Red Lion��� of the French troops, who was ���fighting combat stress after the failed Russian campaign���, saw five horses killed under him that day.

And recent excavation in preparation for the building of a car park, Kershaw writes, ���unearthed a complete skeleton���. ���This soldier may well be one of the many thousands of Wellington���s ���Infamous Army���, unknown and uncelebrated���.

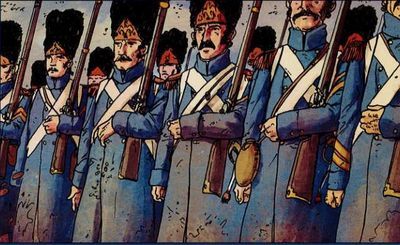

Waterloo being in Belgium, the country of Herg�� and Tintin, there is a new bande dessin��e account of the battle (below), published by Sandawe. Paris-Match, meanwhile, last week had a thirty-two-page special supplement on Waterloo (the French really aren���t entirely avoiding the subject).

For those who don���t really believe that Napoleon died on St Helena in 1821, I can recommend the short novel The Death of Napoleon (1986) by the late Simon Leys, translated from the French by the author and Patricia Clancy and reissued in a new edition by New York Review Books. It���s a gem.

June 17, 2015

A tale of two McBrides

By TOBY LICHTIG

Difficult second novel? Not, on the basis of a reading I attended on Monday night, for Eimear McBride. The Irish author, who won a Hilary Mantel-esque slew of prizes (not to mention critical acclaim) for her brilliant debut A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing was at a Faber Social evening to give us a taster of The Lesser Bohemians. This was the first public outing of a novel slated to appear next year.

McBride has been writing this book for the past decade ��� in fact ever since she finished Girl, which was notoriously rejected by various agents and publishers before finally being picked up by Henry Layte of Galley Beggar Press in 2012. No one, then, can accuse the author or her new publishers, Faber, of rushing to get the second one out there. And if the excerpt we were treated to is anything to go by, we can expect a similarly compelling, linguistically dazzling, emotionally unruly literary bombshell.

McBride ��� who trained as an actress ��� read beautifully from a passage in which the novel���s heroine, an eighteen-year-old drama student, newly living in London, unexpectedly runs into the thirty-eight-year-old man to whom she lost her virginity. The pair immediately begin to flirt, and one thing leads to another.

The syntax and wordplay will be immediately recognizable to readers of McBride���s debut. Posturing banter and self-doubt combine in a cocktail of emotional febrility (���He is laughing and I almost am over my chasing brain���), before the pair head off in pursuit of crispy duck in Soho, the man striding ahead of her (���I���m lagging his gait���). Later, when she gets back to his place, guards, and clothes, are swiftly dropped, ���modesty flying everywhere���.

The tone here is significantly lighter than that of Girl, the sexuality less troubled and destructive, the author allowing herself space to luxuriate in the humour of the exchange. Parts of Girl were very funny, too, particularly when centred on religious hypocrisy, but the narrator of Bohemians seems less angry, less of a victim, or at the very least someone able to take care of herself. McBride has said that this second book, unlike the first, is about ���surviving���. Perhaps it will be less raw (rawness, in the case of Girl, being a major plus point), but I also wonder if it will be more rounded, more panoptic. Either way, everything I heard further increased my appetite for the novel l���m most looking forward to next year.

Before then, however, we can look forward to another long awaited literary McBride ��� this one the heroine of Edna O���Brien���s new novel, her first in ten years, The Little Red Chairs, which is due out from Faber in February. O���Brien���s McBride is a Fidelma (which I���m told is Eimear���s middle name ��� what are the chances?), who falls under the spell of a war criminal in a rural village on the west coast of Ireland. It is, according to the publishers, ���a story about love, the artifice of evil and the terrible necessity of accountability in our shattered, damaged world���.

McBride (Eimear) was clearly a little nervous of performing in front of her own literary idol (���People who say never meet your heroes are liars���, she said), though O���Brien���s presence was anything but austere. Now eight-five, though you���d never have guessed it, she lit up the room with her presence (a clich��, I know, but, really, she sparkled). And, having apologised for the lack of levity in her material, she went on to give a wonderful reading, including a highly amusing passage featuring a garrulous barman (���I do the gym, I do the gym, I do a bit of the cardio���).

If it seemed a little unfair to give these two Irish mega-stars (one the doyenne, one the prot��g�� ��� at least in terms of influence) billing with the other authors on Faber���s forthcoming list, the organisers (unlike this blogger) had the good grace to let the other three go first:

Dan Richards (who co-wrote Holloway with Robert Macfarlane and Stanley Donwood) read from Climbing Days, his forthcoming (spring, 2016) book on mountaineering, set on the trail of his great-great-aunt, the mountaineer Dorothy Pilley. Harry Parker gave us three short chapters from his debut novel Anatomy of a Soldier (2016) set during the recent war in Afghanistan and seen from the viewpoint of a variety of inanimate objects (a tourniquet, a breathing tube, etc). The conceit was interesting though it remains to be seen whether the grimly observed sketches of explosions and surgical emergencies cohere into something like a narrative. And Viv Albertine, formerly of punk band The Slits, (���I���d rather be sharing the stage with these writers tonight than headlining at Glastonbury���) and, more recently, the author of the rock memoir Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. read from a work-in-progress, which ��� I think ��� was called Bag of Truth (apologies if I misheard). It is, according to Faber, ���less memoir and more window on the world as Viv sees it today���. The passage in question was a diligently turned howl against capitalist society and the lack of options for young people who want to be part of a noble cause ��� all read directly from the screen of her Apple Mac. Albertine seemed quite at home on the literary stage. But it was McBride and O���Brien who stole the show.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers