Peter Stothard's Blog, page 16

November 23, 2015

Things being various

By MICHAEL CAINES

Last Tuesday: at the Museum of London I hear Belinda Jack speak about the difficulties of releasing Sylvia Plath���s poetry from the straitjacket of biography and the critical limits posthumously imposed on it by others.

Wednesday: at the Poetry Caf�� I hear Jeremy Noel-Tod point out, in the course of a wide-ranging conversation about modern British poetry and its discontents, that Plath was born in the same year as Geoffrey Hill. Imagine the Collected Poems of a Plath now in her eighties! That would make Ariel an early work. (I recall Professor Jack���s observation of the previous evening that it was Hughes who had labelled everything Plath wrote before she met him ���juvenilia���.) What could a longer-lived Plath (not) have done? What would her influence be now?

The Poetry Caf�� conversation was also the launch for Noel-Tod's The Whitsun Wedding Video. Noel-Tod, the Sunday Times���s regular poetry critic and a lecturer at the University of East Anglia, was joined by his publisher, the poets Emily Berry and Amy Key, and a full house ��� or at least a full Poetry Caf�� basement. Plath���s name came up in the course of an anecdote about the bad old days when, according to one poet of the 1960s, there were no women poets ��� ���there was only Sylvia Plath���.

���And then there wasn���t���, somebody quipped.

Some familiar questions followed ��� questions of narrow canonicity, poetry establishment values and so on ��� along with a mixture of hazy replies (is it sign of critical authority on modernism when somebody has to ask which was published first, ���The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock��� or The Waste Land?) and some more striking remarks. Berry recited a poem first published in the TLS, Astrid Alben���s ���One of the Guys���, a comic account of the terms on which a female poet could be accepted by her male peers, of whom a blotto representative appears in Alben's anecdote ("Are you turning, shurely not, feminissshht?"). Key recited an anaphoric list of demands in response to the recent BBC Poetry Season: ���I want a programme about Claudia Rankine . . .���.

It was also soon established how everybody in the room felt about Philip Larkin. Here Larkin was taken to be emblematic of that notoriously narrow, all but Leavisite canon, a figurehead for the perceived parochialism of the mainstream. (That���s just one way to read Larkin, mind; a realist reading that rejects the Hardy-like strangeness of Larkin���s best work.) Do you like Larkin���s poetry?, the audience was asked. Most hands went up. And do you believe Larkin to be ���culturally central��� for us now? Most hands stayed down.

That was an odd, revealing moment. Who were we to say that Larkin isn���t a crucial, culturally central figure any more? (A whole primetime BBC documentary says otherwise.) Or that a majority in that very room claiming to like Larkin could be anything other than an intimation of his cultural centrality? (Try it with a random group of poetry readers in relation to some of his talented contemporaries: Donald Davie, D. J. Enright, Elizabeth Jennings?)

On the other hand, neither Berry nor Key could claim that Larkin had been a crucial influence on their own work, as he has been for others, which seems perfectly fair enough. The appropriate T. S. Eliot dictum to quote here is from ���Tradition and the Individual Talent���: ���if the only form of tradition, of handing down, consisted in following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes, ���tradition��� should positively be discouraged���. The brief form is: each to her own.

What would have happened if Belinda Jack had conducted the same straw poll in relation to Plath, I wondered? Not that it had been the same sort of occasion ��� the anxious question of influence instead came up in the form of a reference to Harold Bloom. A lecture complete with recordings of Plath talking about her work, with that distinctive Yankee twang in her voice, and a couple of concisely close readings, it restored, for one thing, the ���extraordinarily suggestive, mesmerising, mysterious qualities��� of Plath���s late poem ���Sheep in Fog���. Jack was out to contradict Ted Hughes���s determinedly tragic biographical reading, a pessimistic tracing of a suicide-oriented trajectory from draft to draft. ���It is as though he has installed some monstrous, gigantic machine���, she noted, ���that has dispelled the fog and left the hills there . . . .���

The contradiction was welcome, although there's a lot more to say about Plath, the suicide narrative and other figures significant for the reception of her late work (see Justin Quinn's recent TLS review of The Alvarez Generation by William Wootten, for instance).

Lucidity is a verbal art, of course. It is not that a first glance must reveal nothing ��� only, as in the case of "Sheep in Fog", that time and re-reading will reveal more. ���Shakespeare is a difficult poet���, Roy Fuller asserted in one of his lectures as Oxford Professor of Poetry, ���but then all good English poets have been difficult (with a few exceptions!). The language is in favour of difficulty. . . .���

The Poetry Caf�� conversation continued. There was praise for older poets such as John Ashbery and Denise Riley, whom critics perhaps wrongly tend to assign a wintry role in their own cursus honorum, regardless of the sprightliness with which those poets might write. (Sprightliness, I admit, like feistiness, has its own potentially patronizing overtones.) Transatlantic comparisons were made, attitudes to gender queried. And isn���t the internet a jolly good thing, we could say, when distinctively independent-minded critics such as Charles Whalley and Dave Coates can speak out there? (I would add Charles Boyle; no female critics were suggested.) And then Katy Evans-Bush raised the issue of the digital gap ��� another form of having and having-not ��� and the uncertain future of a fluid medium that depends for its ongoing usefulness on an ���information wants to be free��� ethos.

All this put me in mind of the poet Gerry Cambridge���s observation (mentioned previously on this blog) about the internet upsetting the established ���power structures��� of contemporary poetry ��� ���the old hegemonies seem less significant than energy, imagination and new approaches��� ��� which he set against the ���unsensual��� ghastliness of ���on-screen reading���. The subject comes up again in the course of a symposium published in the magazine Cambridge edits, The Dark Horse: ���the Internet���, the American poet Abigail Deutsch acknowledges, ���makes a lot of poetry happening anywhere in the country available to anyone, anywhere���.

That sounds good. Yet that same symposium begins with the aunt sally assumption that British poetry is still beset by some version of the Movement-led ���gentility principle��� Alvarez inveighed against in the New Poetry anthology of 1962. Can that still be true in the ���anyone, anywhere��� age?

In The Dark Horse, Rory Waterman replies that it isn���t: ���British poetry is really a diverse and not always complementary set of poetries, with a diverse and not always complementary set of champions . . . complicated by Britain being a nation comprised of nations, with one huge and dominant city in its south-east corner���.

As one of this year's judges for the Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets, Waterman offers further testimony to that complexity and diversity in his survey of twenty-four poetry pamphlets from fifteen different small presses, including Clutag, Emma Press, Eyewear, Grey Suit and Shearsman, in the latest TLS. Whether pamphlets serve as a ���nursery slope for poets without a book���, a ���stop-gap for poets between books��� or simply a ���genre in its own right��� (which is how I prefer to see them), they give us plenty of evidence of that not always complementary diversity, a ���rich multifariousness���: the veteran Peter Riley���s ���ethereal, wide-ranging��� Ascent of Kinder Scout; Damilola Odelola with ���something to say about life and youth in our times���; Laurna Robertson���s ���pellucid yet complex��� collection inspired by her native Shetland; Eveline Pye���s ���startling��� vision of Zambia; and many more besides. The winners of the Michael Marks Awards will be announced at the British Library tomorrow evening.

Thursday: at the British Library, I find the poetry section of the bookshop. There are no surprises there at all ��� Plath, Larkin, Hughes, a marvellous but lucky few more. But so much more is out there, somewhere. And so much more is in the books you only think you���re finished with. Why not have a look for it? All of it.

November 20, 2015

Alice at the British Library

By MICHAEL CAINES

Alice in Wonderland suffered a false start. The Reverend Charles Dodgson's immortal nonsense first appeared in print 150 years ago, in the summer of 1865, only for that first edition to be withdrawn after its illustrator John Tenniel complained about the quality of the printing. The reset edition, dated 1866, was available from November 11. Dodgson ��� or Lewis Carroll to the public ��� imagined he would lose ��100 on the book, after an initial outlay of ��600. He imagined perhaps issuing the book again and breaking even ��� "but that I can hardly hope for". You probably know the rest of the story ��� although not necessarily as it's presented at the British Library from this week onwards . . . .

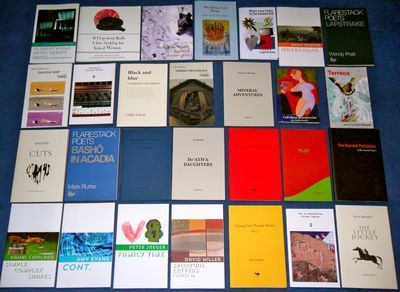

The BL's new free Alice in Wonderland exhibition (just a skip or struggle up the stairs from the ground floor) tours the world of Wonderland from conception (a boat trip with three daughters of the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, and the superbly named Robinson Duckworth, a friend from Trinity College) to illustrated editions of the twenty-first century. Here is the Wonderland manuscript, illustrated by the author, and the Tenniel woodblocks (only recovered from the publisher's bank vault in 1985); but also various attempts to outdo Tenniel by Arthur Rackham (typically fey, menacingly grey):

Leonard Weisgard (note the unconventionally red dress, in contrast to the customary blue):

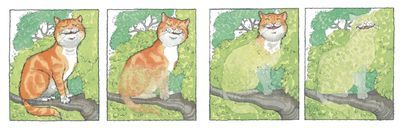

And Helen Oxenbury (a self-camouflaging Cheshire Cat with eyes closed, unlike Tenniel's more watchful predecessor):

These are set alongside Willy Pogany's "Flapper Alice" of 1929 (with its chorus lines of playing card courtiers), a wartime Alice in Wunderground by Michael Henry Barsley (rationed to a "Molotov Bread basket" at the Mad Hatter's tea party), Salvador Dal��'s unimpressive 1969 effort, John Vernon Lord's politically daubed version of 2009 (with Alice's words printed in pinafore-blue) and a characteristically spotted revision from Yayoi Kusama. There is also a listening post for those who wish to hear nonsensical delights such as the Wonderland Quadrille and plentiful evidence of Alice-the-brand, in the form of a jigsaw, a spinning top (aptly adorned with the White Rabbit's rushing words: "I'm late, I'm late . . .") and the postage stamp case pictured above. This last item seems especially appropriate given that line in the "Looking-glass Insects" chapter of Through the Looking-glass, in which our heroine finds herself on a train, only for a fellow passenger to suggest an alternative means of transport: "she must go by post, as she's got a head on her . . ." ��� "head" being Victorian slang for a postage stamp.

I'm grateful to the friend who also attended the press view for pointing out that the captions are not entirely to be trusted ��� friendship is a slightly misleading term for Carroll's relations with the Rossettis. And I think the point about Carroll's making the most of his success by encouraging translations of his work (a subject exhaustively explored in this recent publication from Oak Knoll Press), a "nursery" edition and so on needs qualification: by examining his bank account records, Jenny Woolf has shown in The Mystery of Lewis Carroll that he never made an outrageous fortune from Alice. There is an Alice biscuit tin, but "by modern standards, this merchandising was very modest indeed".

(Who was Carroll's inspiration for the Mad Hatter, by the way? Here's one recent identification of a real-life "Oxford eccentric", published in the TLS a couple of years ago.)

With thanks to Lindsay Duguid.

November 19, 2015

Art as knowledge?

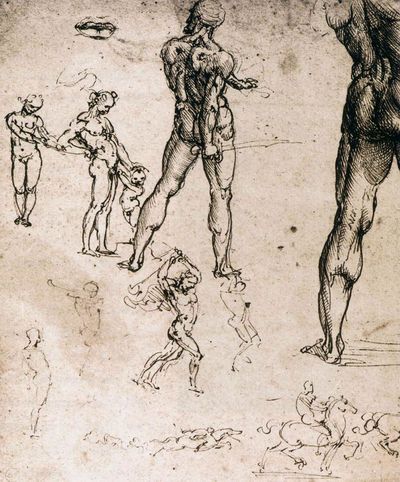

Leonardo da Vinci, figure study, 1505

By GABRIEL ROLFE

���Art as Knowledge?���, a discussion held at the London School of Economics last week, was the latest instalment in its now-twenty-year-old Forum for European Philosophy. The intellectual component in art, the climate of art���s reception and the social standing of the artist were all touched on, suggesting just how fertile this question is ��� even if the speakers kept their distance from an answer.

In the early Renaissance, painter and sculptor fought for inclusion in the so-called liberal arts. The theoretical writings of Leon Battista Alberti and Lorenzo Ghiberti gave unprecedented attention to the intellectual and inter-disciplinary knowledge required of the artist, which included philosophy and mathematics. In Leonardo da Vinci���s writings, we find the first exaltation of a unique knowledge belonging to the artist: the understanding of perspective. But the purview of this evening���s discussion was emphatically modern.

The chair of the discussion, Vid Simoniti, steered things with a playful off-handedness. He didn���t have much choice, settling down with an apology for the absence of Alexander Massouras ��� the panel���s sole practising artist was caught in traffic. Cottoning on to the sighs, Simoniti played it off as less disappointing than fitting ��� Plato had, after all, cast out the artist from his republic. But Aristotle took pity on the poor soul; and now here we were.

At this point, Matthew Kieran, Professor of Philosophy and the Arts at Leeds University, cleared his throat. He sketched for us an antagonist: the sceptic for whom art has no knowledge of its own whatsoever ��� it is simply telling us what we already know, from psychology, anthropology and science generally. Kieran almost lost himself in this dark ventriloquy, before reminding the room that, as an old-fashioned, paid-up humanist, he didn���t believe it. He pointed out a projection on the wall of the French artist JR���s "Women Are Heroes", in which eyes have been painted on the fa��ades of Rio���s favelas ��� the eyes of its female inhabitants. Conceding that the image may not impart any new knowledge as such, Kieran suggested that it made a kind of emotional understanding possible.

Neither he nor the audience seemed thrilled by this. Whether the ���emotional��� is a criterion for appraisal in itself was not pursued.

Kathleen Soriano, former director of exhibitions at the Royal Academy, brought a new image to bear ��� one central to the RA���s recent Anselm Kiefer retrospective, which she curated. "Ashflower" now hovered on the wall. Soriano relayed her experience of conceptualizing that show with Kiefer. She insisted that Kiefer���s intellectual ���seriousness��� ��� his monumental sublimations of history, poetry, philosophy ��� was both a tortured inward turn and an engagement with public discourse. But she agreed with Kieran that art consumes other knowledge, and ventured that, in exceptional instances such as Kiefer���s, art is capable of viscerally transmitting that knowledge into a ���common language���.

At this point, hands flew up in indignation. A flustered Kantian asked Kieran and Soriano to stop politely avoiding the business of aesthetics. With eerie ease, the panel offered their placation: ���some things are just beautiful���, and sure, art can be ���not about meaning���. Another audience member then decried the exclusive attention being given to the ���Western eye���.

A different energy wandered in with the belated panellist Alexander Massouras, painter and Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at Ruskin College in Oxford. His personal insistences were raw and winning. Of one of his own paintings, now being projected (from the series Nine flare paintings with octagonal aperture I, 2012���13), he recalled: ���I might have written an essay, but the ideas seemed more economically expressed in a painting���. Soriano interjected that there surely must have been a sense of the visceral, of the unthinking, to it. But Massouras either couldn���t or wouldn���t accept a distinction between an intellectual inspiration and the painting itself.

What Walter Pater once called ���true pictorial quality��� ��� the ���knowledge��� that physical, compositional elements such as form and line represent ��� remained disquietingly off the table. We are some way from the time when artists struggled to escape the standing of mere artisans. As Massouras matter-of-factly explained, the social imperative is now towards intellectualization, towards ���Theory���. And for the most part, the LSE Forum exemplified this. The artist���s struggle, then, is getting back to craft.

November 18, 2015

Tea at Dr Johnson's House with David Garrick ��� and Charlotte Lennox

By MICHAEL CAINES

On Sunday evening, I eavesdropped on a conversation at Samuel Johnson's house. The writer Charlotte Lennox and the great man himself began it; they were soon joined by Dr Johnson's former pupil, the actor David Garrick. The subject of their chat was a play: King Lear.

They sipped their dishes of tea, and disputed. What had Shakespeare done with his sources? How had Nahum Tate and Garrick, in turn, "improved" on Shakespeare? And now what was Johnson going to do with it, since he was meant to be editing this most unbearably unjust of tragedies for his edition of Shakespeare's plays? . . .

How dare you suggest that I've been hallucinating again. I'm obviously talking about Palimpsest's Playing to the Crowd, a dramatized account of how such a conversation might have run in 1756. According to Katherine Tozer, the author of Playing to the Crowd, the answer is: not very smoothly. Johnson (played by Mark Elstob) is annoyed that Garrick won't trust him with his precious early editions of Shakespeare. Garrick (Nick Barber) brings along his own acting version of Lear and spends most of the time playing the buffoon. Mrs Lennox (Tozer herself) traces the Lear's history, remarking on where, in her view, Shakespeare got it wrong.

By coincidence, the New Statesman mentioned Lennox the other week, in the course of a somewhat muddled announcement about a new literary prize. She appears there as the author of prose fiction ��� perhaps principally for the sake of The Female Quixote, a witty hit of 1752 ��� alongside a few other eighteenth-century women novelists. "When we do remember them", the NS opines, lumping together writers as different as Lennox, Delarivier Manley and Mary Hays, "it is through the eyes of male writers", which certainly isn't true of modern scholarship. Pope's unpleasant references in the Dunciad to Eliza Haywood and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu duly follow, presented as if he had it in for them alone, and not for them plus a considerably greater number of male writers.

It would have been better, perhaps, to stick to Lennox, whose literary career was indeed to some extent dependent on how a male writer saw her ��� albeit mostly positively ��� that writer being Dr Johnson.

Johnson said a vile thing when told by James Boswell of a woman preaching at a Quaker gathering: "a woman's preaching is like a dog's walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all". But reviewing Kate Chisholm's Wits and Wives: Dr Johnson in the company of women for the TLS, Frances Wilson could quote his contrasting assertion: "it is a Paltry trick indeed to deny women the cultivation of their mental powers, and I think it is partly a proof we are afraid of them". As testified by both Chisholm's book and Dr Johnson's Women by Norma Clarke, Johnson himself was unafraid. Literary female friends included the classicist and poet Elizabeth Carter, the "Queen of the Blues" Elizabeth Montagu, the high-minded Hannah More and the brilliant young Frances Burney. And according to Boswell (who may have had an ulterior motive for saying this, admittedly), Johnson could say, after dining with Carter, More and Burney, that "Three such women are not be found"; yet Lennox he thought ���superior to them all���.

It was Johnson who had welcomed Lennox's first novel, The Life of Harriot Stuart (1751), with an all-night party in her honour, at which he presented her with a apple pie ��� "stuck with bay leaves, because, forsooth, Mrs Lennox was an authoress, and had written verses". Boswell's rival biographer, Sir John Hawkins, recalled that Lennox's champion "had prepared for her a crown of laurel, with which, but not till he had invoked the Muses by some ceremonies of his own invention, he encircled her brows". He went on to advise her on literary matters, and write dedications for her books, including one for The Female Quixote. He may even have written a part of that novel; he certainly reviewed it (his only review of a novel) and quoted it several times in his Dictionary.

Lennox had her difficult side: she appeared in court in 1778, for beating her maid. That side of her personality doesn't come through in Playing to the Crowd, although a coarse remark from Johnson does cause her to walk out at one point. She had a habit of losing friends, and was seldom far from the irresistible Grub Street poverty trap.

Her most historically significant achievement perhaps isn't in prose fiction. (Terry Castle, for one, thinks The Female Quixote ���heartless and mediocre���.) No, I suspect it's Shakespeare Illustrated (1753���4), a pioneering attempt to account systematically for Shakespeare's sources.

This is is a ���far more critical account��� of Shakespeare than, say, Elizabeth Montagu���s adulatory Essay on Shakespeare of 1769. Garrick and Johnson were both dismayed, but, as Playing to the Crowd faithfully shows, could hardly disagree about, say, the brutality of Shakespeare's Lear. "This Fable, although drawn from the . . . history of King Lear, is so altered by Shakespear, in several Circumstances, as to render it much more improbable than the Original." Lear does not run mad until the third Act, Lennox observes, but is made to act madly from the outset. The promising of Cordelia to the King of France is managed "unartfully". The end of the play violates "poetical Justice", that hackneyed but potent charge. (Garrick stuck to Tate's idea of a happy ending.) The "Adventure of the Rock", meaning Dover Cliff, is "heightened . . . with too little Attention to Probability".

The boldness of Shakespeare Illustrated has implications beyond its immediate subject, as Emily Hodgson Anderson has noted in the TLS: it constituted "one way of showing intellectual equality between the sexes". Johnson was comfortable with that aspect of things ��� he made use of Lennox's research in his own Shakespeare edition, after all ��� but the dedication he wrote on Lennox's behalf is "highly ambivalent" about the book it prefaces. One modern reader, Jonathan Brody Kramnick, has seen that book as "an argument on behalf of the novel" in the guise of an attack on Shakespeare's improbabilities and indecencies. Was it entirely a joke when Johnson suggested that she go on to "illustrate" another supposedly unassailable poet, Milton, after she has "demolished" Shakespeare? A "bird of Prey", he called her, "but the Bird of Jupiter."

In Playing to the Crowd, Lennox is sometimes reduced to playing the umpire between Johnson and Garrick's endless, affectionate yet difficult dialogue, between the scholarly authority and his preening prot��g��. (This is the second time this year, incidentally, after Mr Foote's Other Leg, that I've seen a play by an actor in which Garrick, one of the all-time greats, is presented as some kind of vapid fool.) It's an enjoyable compendium of quotable moments, a three-hander anthology of eighteenth-century-isms ��� but next time round, if there is a next time round, I'd like to see the forthright Mrs Lennox given her own show.

November 17, 2015

Waking the feminists

By JAKI McCARRICK

On October 28, the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, announced a programme of ten new plays, Waking the Nation, which will mark the centenary of the Easter Rising in 1916. It was soon noticed that only one of the plays was written by a woman ��� hence a new movement, #wakingthefeminists, which has had a lot of attention in the media: see articles by Una Mullally, Martina Devlin, Sara Keating and Emer O���Toole. In a feature for the Irish Times, Fintan O���Toole refers to the funding (half a million euros) awarded to Waking the Nation by the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, stating that ���astonishingly, the department admits that at no point did it seek to discover what the money would actually fund. The discussions were about the scale of the project, not its content���.

With Lian Bell and Sarah Durcan at the helm, #wakingthefeminists rallied a number of female artists to speak about parity in the arts at the Abbey Theatre and in Ireland more generally. Chaired by the Labour senator Ivana Bacik, the meeting took place at the theatre on Thursday, and I attended along with more than 500 of Ireland���s artists, writers and theatre-makers . . . .

Thirty noted figures gave powerful accounts of their experiences as "women artists" in Ireland. The playwright Amy Conroy said: ���we will not accept anything less than equality. No ifs, no ands, no buts���. The director Catriona McLaughlin said that ���no longer can women���s voices be neutered or ventriloquized���. Actors such as Derbhle Crotty and Janet Moran deplored the lack of plays written or directed by women. The London-based Irish playwright Nancy Harris could even say: ���we don���t know what women are writing because we are not hearing them enough���. And the playwright Gina Moxley brought the house down; ���we are not asking; we are coming in���, she said.

After these moving and often humorous speeches, it was over to the Abbey Theatre���s Artistic director, Fiach MacConghail, who admitted that he had ���failed to check his privilege��� and did not have gender balance in mind when programming the events for next year. Finally, the overall objectives for the #wakingthefeminists campaign were reiterated: equality for women artists; a sustained policy for inclusion with an action plan and measurable results; equal advancement of women artists; economic parity for all working in the theatre.

As I mentioned in a TLS review published earlier this year, since the new Abbey Theatre building opened in 1966 there have been six plays on the main stage by women ��� one each by Edna O���Brien, Jeanne Binnie and Elaine Murphy and three by Marina Carr. Over the same period there have been approximately 320 plays by men. The Abbey���s smaller Peacock Theatre has staged comparatively more work by Irish female playwrights, and overall the figure of total work by women at the Abbey is around 12 per cent (1.8 per cent on the main stage) of all programmes. We would do well to remember that there would be no Abbey Theatre were it not for the pioneering work of Lady Gregory as well as that of W. B. Yeats, and Annie Horniman's money allied to William Fay's management skills.

In their introduction to the book I reviewed, Irish Women Dramatists 1908���2001, Eileen Kearney and Charlotte Headrick suggest that the long neglect of female writers in Ireland has a lot to do with the financial risk involved in staging new plays ��� and with the female voice itself. They quote Linda Hart, who states in Making a Spectacle: Feminist essays on contemporary women���s theatre: ���The woman playwright���s voice reaches a community of spectators in a highly public place that has historically been regarded as a highly subversive, politicized environment . . . thus the woman who ventures to be heard in this space takes a greater risk than the woman poet or novelist���. There are other factors to consider: as Kearney and Headrick point out, ���the expansion of women���s rights on this unsceptered isle was a slow if steady uphill battle���, and until recently ���the Irish State���s laws and social provisions remained repressive of liberty in the two areas of sex and work���. In Ireland, there was a bar on hiring married women in the Civil Service until 1973.

In the UK, meanwhile, the National Theatre has staged hardly any plays by women on its main stage (Sarah Kane is to get her debut there with Cleansed, directed by Katie Mitchell, in February 2016). It's the same in the US. The Dramatist Guild of America states in its recent magazine that

���it was found that the percentage of women being interviewed, doing the interviewing or being the subject of the story ��� was exactly 20%. In the art museums, 80% of the art hanging on the walls is by men. The women���s work is stored in the basement. In orchestras, until the advent of blind auditions, 20% of the players were women. This 20% number is the real ceiling we are fighting in our lives and in our careers today���.

The same piece also points out the dangers of a situation in which women���s voices are silenced: ���the culture goes into what a UN friend of mine calls testosterone poisoning; women are the safety valve on the culture���.

What the next stage is for the Waking the Feminists campaign remains to be seen. Certainly, it has been a powerful agent of pressure and self-examination in Irish arts institutions. The playwright David Hare said in a recent BBC4 interview that ���it is the job of subsidized theatre to lead rather than follow��� ��� in which case, this could be an important moment for the Abbey Theatre, and for the arts in Ireland in general.

November 16, 2015

Colour-conscious

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Your eyes strain; your sense of depth has gone; you feel suspended in a coloured mist; grey silhouettes emerge every now and then beside you. This is ���yellowbluepink���, an immersive, dizzying new art installation by Ann Veronica Janssens at the Wellcome Collection, London, that aims to push the limits of how our brains interact with the world. Consciousness ��� meaning both whether we���re awake (or are we?) and what we���re conscious of (our perceptions, thoughts and emotions) ��� continues to baffle us. Is my experience of being me really any different to your experience of being you? And how can I, or you, explain it? Well, here (at least some of it) goes . . . .

For me, wandering around the gallery the other day, panic mixed with euphoria. You can���t see where the walls are, where the doors are, where other people are. We were told not to lie down on the floor; you can imagine the problems with that. Janssens���s installation is simple ��� coloured lighting gels and a smoke machine ��� but not simplistic. Like Antony Gormley���s ���Blind Light��� at the Hayward Gallery in 2007, an interior space that you assume is safe and familiar is questioned; and so are your senses. You feel as though you���re up a mountain (below, for example, is a photograph I took a few years ago of a friend at high altitude in Munnar, India, where I had a similar experience) or under the sea ��� that���s certainly the response Gormley and Janssens want to prompt, with a little fun along the way.

India, 2012. Copyright Mika Ross-Southall

India, 2012. Copyright Mika Ross-Southall

In an accompanying leaflet, Professor Anil Seth suggests that our conscious sense of our surroundings is sometimes (always?) determined by our brain���s ���best guess��� of what���s causing such ambiguous signals. The museum���s curator, Emily Sargent, adds that during the installation ���attention is focused on the process of perception itself���, for entering the gallery ���is to submit to colour as a physical entity, to be subsumed by the experience of seeing���. This dense, coloured mist wrapping itself around you is almost touchable. Disorientating (your eyes continuously try to adjust themselves), but enjoyable and uplifting, partly thanks to the choice of bright colours. It's not often that we're forced to turn in on ourselves and be in the present moment like this. The space is real, the time is real; yet none of it feels quite real.

Janssens���s piece is a heady aperitif to the Wellcome���s forthcoming exhibition, States of Mind: Tracing the edges of consciousness, which opens in February next year, exploring all those phenomena (such as sleepwalking, dream-states, synaesthesia, anaesthesia, memory loss) that are yet to be fully understood.

The Wellcome Collection doesn���t have much of a reputation for displaying cutting-edge artwork, but here we have a wondrous exception. (Indeed, at some points, the wait for Janssens���s piece, which is on until January 3, has been up to two hours ��� I suggest dropping in off-peak.) I hope it means there���s more to come, because, for a non-scientist like me, it���s a brilliant, instinctive way of understanding more about these complicated ideas. And isn���t that what art should do? Make you think, question yourself and help to explain the world around you.

November 14, 2015

All too rare Ben Jonson

By MICHAEL CAINES

Ben Jonson is mentioned only twice in Daniel Rosenthal's "definitive" history of the National Theatre, according to the book's index: once as the author of Volpone, staged at the NT in 1997; and once more as the author of Bartholomew Fair, a "panoramic snapshot of 1630s London at play". (That second mention is particularly impressive, given that Bartholomew Fair was first performed in 1614.)

In an appendix, however, Lyn Haill handily lists every NT production up to 2013; and Jonson's name appears more often there. How often exactly? Well, six times, by my (admittedly rather hasty) count. That's three Volpones, two Alchemists and one Bartholomew Fair. Guess how many NT productions of Shakespeare there have been over that same period ��� and if hastily compiled statistics are your thing, read on for the answer . . .

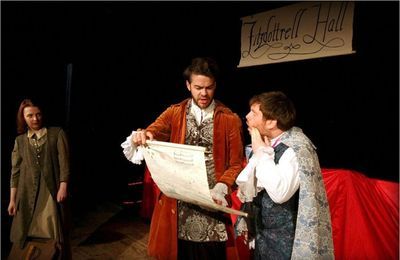

Seeing The Devil Is an Ass by Jonson revived at the Rose Playhouse recently, I could only admire the theatre company's good taste ��� and the cast's farcical energy ��� but feel sorry about their lack of resources. (The show has had mixed reviews.) A friend of mine was also on the south bank of the Thames that night, watching As You Like It in the NT's Olivier Theatre. We compared notes. I wouldn't be surprised if the set alone for Shakespeare's comedy cost more than Mercurius's entire budget for Jonson's.

Imagine, as I wistfully did, that the buskin were on the other foot: Shakespeare on the fringe, Jonson as the national treasure. The Devil Is an Ass in the Cottesloe with much suitably gorgeous deception of the senses. The Staple of News as a bustling house in the Olivier, "Where all the news of all sorts shall be brought". Every Man in His Humour given the kind of sharp dramaturgical treatment The Beaux' Stratagem recently received. While Fluellen, downstream at the Rose, administers Pistol's beating with a cudgel padded out with gaffer tape.

Not that the NT alone is responsible for Jonson revivals ��� the RSC seems to have done right by him over the years. My flight of theatrical fantasy did make me wonder, though, exactly how well Jonson and his contemporaries have fared on the South Bank. And I wasn't surprised to see that, out of a total of some 800 productions, there has been surprisingly little adventuring away from the tried-and-tested few plays from the supposed "Golden Age":

70 productions ��� William Shakespeare (most of the canon)

6 ��� Ben Jonson (see above)

4 ��� John Webster (the obvious two)

3 ��� Christopher Marlowe (Tamburlaine, Dido Queen of Carthage, Edward II)

2 ��� John Ford ('Tis Pity She's a Whore twice); John Marston (The Dutch Courtesan, The Fawn); Thomas Middleton (Women Beware Women, The Revenger's Tragedy); Thomas Middleton and William Rowley (A Fair Quarrel, The Changeling)

1 ��� Thomas Dekker (The Shoemaker's Holiday); Thomas Heywood (A Woman Killed with Kindness); Thomas Kyd; Christopher Marlowe adapted by Bertolt Brecht (Edward II); Thomas Middleton and William Shakespeare (Timon of Athens)

None whatsoever ��� Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, let alone Beaumont or Fletcher; John Lyly; George Peele; James Shirley; Richard Brome; and from later in the century, there's no sign either of Aphra Behn . . .

Meanwhile, and perhaps more surprisingly, things are not that different at Shakespeare's Globe, which, living up to its name, has to date found time for only four Marlowes, two Fords, two Middletons, several very fine one-offs ��� and no Jonson at all. Although the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse offers a tempting but comparatively unoriginal selection of Shakespeare's late plays this season, it ought to improve on that dubious record in the future.

This is not to bash either the Globe (which also runs the excellent Read Not Dead series of staged readings) or the NT (which has enough living playwrights clamouring to be heard there as it is without the dead ones, or their vicarious representatives, coming back to haunt it; the under-representation of female playwrights at the NT, as in Irish theatre, is obviously a more urgent issue). Of course, no big theatre can afford to ignore the demands of tourism and the school syllabus. The same appendix that furnishes me with these statistics also offers information about how well attended each production was. It seems that not many non-Shakespearean productions can match Nicholas Hytner's production of Henry IV parts 1 and 2, in which Michael Gambon played Falstaff: it enjoyed all but full houses throughout the run.

I think this is, nonetheless, a sorry state of affairs for admirers of Jonson, "Britain's first literary celebrity", and other playwrights of his era. And I suspect that the theatre business's highly selective memory acts as a counterpart to what Clifford Siskin has called the "Great Forgetting" in literature ��� the kind of collective amnesia that underpins the vaunted "Great Tradition". Here's hoping for gloriously diverse seasons at the SWP in the future, and the realization of the Rose's ambitious plans to turn its makeshift space into a fitting new home for (for example) Pug, Fitzdottrel, Meercraft and all who inhabit the humorous world of Jonson's imagination.

November 13, 2015

Eugene Vodolazkin and his 'non-historical' novel

By BRYAN KARETNYK

Against the usual backdrop of rush-hour traffic along Bloomsbury Way, Pushkin House played host earlier this month to the launch of the English-language edition of Eugene Vodolazkin���s novel Laurus. With an audience made up primarily of Russians, however, the discussion showed a certain linguistic flexibility, with both author and interviewer ��� Dr Josephine von Zitzewitz of Cambridge University ��� switching acrobatically between Russian and English, ably assisted by Alexei Stephenson, the evening���s interpreter.

Vodolazkin is by day a scholar of medieval manuscripts in the Department of Old Russian Literature at Pushkin House (the venue���s academic namesake in St Petersburg); and his love of ��� and profound expertise in ��� medieval literature truly shone though. Fresh from a talk the previous evening at St Antony���s College, Oxford, where the topic under discussion was ���Contemporary Russian Literature through the Eyes of a Mediaevalist���, Vodolazkin now had the chance to reflect personally on how these literatures combine in his own work.

Laurus, which has already been translated into more than twenty languages worldwide, was Russia���s literary sensation of 2013, scooping both the Big Book and the Yasnaya Polyana awards. This, Vodolazkin���s second novel (though his debut in English), captures religious fervour in fifteenth-century Russia, tracking the life of a healer and holy fool in a postmodern synthesis of Bildungsroman, travelogue, hagiography and love story. ���To quote Lermontov," he said, ���it is ���the history of a man���s soul���.��� However, when von Zitzewitz touched on the significance of the work���s subtitle (���a non-historical novel���), Vodolazkin was quick to dissociate himself from historical fiction. His is ultimately ���a book about absence," he said, ���a book about modernity���. ���There are two ways to write about modernity: the first is by writing about the things we have; the second, by writing about those things we no longer have.���

While Vodolazkin may resist the label of historical novelist, he soon enough gave the audience to realize that time, nonetheless, is a crucial factor in his thinking ��� both as an artist and as a scholar. He spoke engagingly of the medieval obsession with time and its reckoning, giving a fascinating account of the calculations that led to a widespread belief that the world would end in 1492 (or 7000 Anno Mundi). Even later, he told us, in 1700 (after God had ���postponed��� the apocalypse), there was an uprising of Old Believers when Peter the Great proclaimed a new calendar that was at odds with their counting: they consequently dubbed him the Antichrist for having introduced an eight-year void in which no one had lived.

When asked about the language of the period and the challenges it brought to Laurus, Vodolazkin wryly admitted that having worked for more than thirty years on Old Russian manuscripts, he was probably better read in medieval literature than modern. ���Without any false modesty, I think I can say I���d make a decent Old Russian writer���, he quipped, with an undertone of absolute seriousness. He went on to describe how, after some encouragement from his wife, he first tried his hand at writing in the idiom of the period. He quoted from memory ��� first in Old Russian, then giving a modern translation ��� several sources that inspired his work, and it was touchingly apparent that these vitae, these ���lives��� of the saints, are indeed still very much alive to him.

Questions followed; when the inevitable one arose, about what the public could expect from this author in future, he gave us a hint: a new novel called The Aviator. ���All I need is another two or three weeks to finish it off���, he said. ���The difficulty is finding the time.���

Laurus will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

November 12, 2015

Staging a Revolution

Maryna Yurevich and Aleh Sidorchyk in Discover Love

By ALAN MURRIN

Last week I received a text message instructing me to be in the forecourt of St Leonard���s Church, Shoreditch High Street, at 6:20pm on Friday. ���Please remember to bring cash, ID and warm clothes���, the message read. I wasn't sure how seriously to take these instructions, but I put my provisional driving licence in my wallet and headed for the designated location. I counted fifty people in the churchyard. Eventually, we were divided into small groups and guided silently to a railway arch on the other side of Kingsland Road.

The railway arch had been transformed into a stage set by the Belarus Free Theatre (BFT) for a performance of Discover Love, a staple of their repertoire. The show is just one of eleven individual productions being staged during a two-week celebration ��� ���Staging a Revolution��� ��� of the tenth anniversary of the Belarus Free Theatre. The celebration began with a week of performances and discussions at undisclosed locations in London and concludes with a week of shows at the Young Vic, where the group have been an associate company since they were granted political asylum in the UK in 2011. The show was introduced by the BFT co-founder Natalia Kaliada, who gently admonished us for not bringing our passports; attending a BFT production in Belarus is a serious business and, if you are detained by the authorities, having your passport to hand means fewer hours in custody. We were then introduced via Skype to our Belarusian counterparts, who were watching events unfold from Minsk.

Discover Love tells the true story of Irina Krasovskaya and her husband Anatoly, a successful businessman. It begins as a traditional love story detailing their courtship and marriage and the difficult early years when they struggled to bring up their daughter in economically and politically uncertain times. Their support for each other is unerring. The action unfolds as a series of playful vignettes that are gradually darkened by the tragedy that befalls the couple. The world that surrounds Irina is revealed as one of horror, brutality and deceit. One day in 1999, Anatoly told his wife that he would be spending the evening with some friends and that he would be home later that night. Irina never saw her husband again.

After the performance, beetroot soup was served and some of the audience sat cross-legged on the stage supping from paper bowls. The discussion that followed, however, was sobering. The topic was ���the problems of forgiving and forgetting���, and Irina Krasovskaya herself was in attendance to add to the account of her experience that we had just watched. Anatoly Krasovskaya���s car was discovered but his body has never been found, and his name has simply been added to the ever-growing list of ���the disappeared���. (It is noteworthy that the UK is one of the few Western European governments not to sign the UN Convention Against Enforced Disappearances.) For the talk Irina was paired with Marina Cantacuzina, the founder of The Forgiveness Project; the chair was BBC Scotland���s Kaye Adams, who mediated between the speakers and an audience who were still very much trying to process what they had just seen. It became apparent that ���forgiveness needs a face���: in order for the victim to forgive, the perpetrators of the crime must be brought to justice; the men accused of murdering Anatoly Krasovskaya never were.

Questions asked by audience members about the justice system in Belarus helped to clarify a situation that was otherwise baffling to a Western European audience. The overwhelming impression was one of a country forsaken by its more powerful European neighbours because its situation is simply not dire enough to demand immediate attention. Belarus has been dubbed Europe���s last dictatorship; Alexander Lukashenko has been President for twenty-one years. (See Jim Dingley's piece "Svetlana Alexievich: Another controversial Nobel?", October 12.)

Talk turned to artistic intention, and whether a piece of theatre can effect any kind of immediate change. Much has been made in the past few years of theatre in London being ���immersive��� and ���experiential��� in ways that are largely arbitrary. Watching the nightmare that one woman experienced, and having that horror compounded by the presence of the individual who suffered it, was about as real and visceral as theatre can get.

To support the Belarus Free Theatre, visit www.belarusfreetheatre.com.

November 11, 2015

Does philosophy have to be obscure?

By MARINA GERNER

I recently went to a public lecture at LSE hosted by the Forum for European Philosophy. The discussion was entitled ���Does philosophy have to be obscure?��� It struck me as a bit odd that both possible responses presume that philosophy is indeed obscure. If we understand ���obscure��� as ���unclearly expressed��� or ���not easily understood���, so many things seem more obscure ��� Facebook���s terms of agreement, say, or the Starbucks tax situation ��� than discussions of the good life or free will. After all, it was a philosopher, John Searle, who said: ���If you can���t say it clearly, you don���t understand it yourself���.

The small lecture theatre was filled with an upside-down demographic pyramid; about three-quarters of the audience were over the age of sixty-five. Around the speakers' table were Andrew Benjamin, a Professor of Philosophy at Kingston University; Joseph Schear, Lecturer in Philosophy at Oxford University; and Simon Swift, Lecturer in Critical and Cultural Theory at the University of Leeds. If it hadn't been for the presence of Danielle Sands, Lecturer in Philosophy at Royal Holloway, who chaired the event, I would have said "Congrats, you have an all male panel!", much like this tumblr; but I���m not going to dwell on female philosophers this time.

Obscurity always raises the question: obscure to whom? There���s no such thing as obscurity in the abstract, argued Joseph Schear. He mentioned three situations in which philosophers might say that obscurity is necessary.

In Persecution and the Art of Writing (1952), Leo Strauss put forth the historical thesis that ancient and early modern philosophers, in order to escape persecution, used obscure language to disguise their most heterodox or controversial ideas.

Second, there is the critical theorists��� argument that one ought to write inaccessibly, to evade the ���alienation of being turned into a mass-market commodity under conditions of capitalism���. Adorno said: ���Advocates of communicability are traitors to what they communicate���. So if you think of your audience as ���cogs in the administrative life of capitalism��� then the practice of obscurity might be considered a tactic of resistance.

Third, there is the Socratic response. Socrates set out to challenge the arrogant knowingness of his contemporaries, the Sophists. His aim was to render purportedly known things obscure, to clear the ground for a more genuine understanding. His art is not one of inaccessible language; it���s the ���simple yet rare persistence to ask and then linger���, with a question like: what is courage?

Simon Swift, who apologized for not being a philosopher, need not have done so, because he very aptly cited Paul Celan���s insistence on obscurity���s importance in poetry. ���Leave the poem its darkness���, pleaded Celan; ���maybe ��� maybe! ��� it will give, when the excessive brightness which the exact sciences know already today to put before our eyes, will have changed the very ground of the human genotype���. Then obscurity will ���provide shade in which man can reflect on his humanity���. We still live in the great age of appearance, argued Swift; we need the obscure to leave space for what gets lost in the world of the exact sciences and the extreme brightness of our age.

Imagine you���re holding a cube in your hand made of either salt or sugar, said Andrew Benjamin with a nod to Hegel. An empiricist holding the cube will say: I can feel the pointy bits of the cube, I can see its whiteness, and my tongue can taste its sweetness. All these properties are empirically there ��� but not the coherence of these elements. Society does not consist of a series of identifiable empirical events. That is why philosophy moves beyond ���the naivety of empiricism��� into obscurity; this is where discussions and matters of judgement thrive, in what Hannah Arendt called the "space of appearance". Obscurity is ���ironically there to bolster democracy���.

The speakers presented three very clear explanations as to why philosophy might need obscurity. But as the floor was opened to questions from the audience, the water became increasingly muddied. ���We can wait until you like a question���, said the chair to the panel, after a few obscure questions were met with nonplussed faces. ���Two questions, three blank faces��� aptly summed up another round of questions, and then came one of my all-time favourite instructions to the audience at talks of this kind: ���Please can you phrase your comment as a question?��� Once the chair managed to clarify the questions, clear answers followed.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers