Things being various

By MICHAEL CAINES

Last Tuesday: at the Museum of London I hear Belinda Jack speak about the difficulties of releasing Sylvia Plath���s poetry from the straitjacket of biography and the critical limits posthumously imposed on it by others.

Wednesday: at the Poetry Caf�� I hear Jeremy Noel-Tod point out, in the course of a wide-ranging conversation about modern British poetry and its discontents, that Plath was born in the same year as Geoffrey Hill. Imagine the Collected Poems of a Plath now in her eighties! That would make Ariel an early work. (I recall Professor Jack���s observation of the previous evening that it was Hughes who had labelled everything Plath wrote before she met him ���juvenilia���.) What could a longer-lived Plath (not) have done? What would her influence be now?

The Poetry Caf�� conversation was also the launch for Noel-Tod's The Whitsun Wedding Video. Noel-Tod, the Sunday Times���s regular poetry critic and a lecturer at the University of East Anglia, was joined by his publisher, the poets Emily Berry and Amy Key, and a full house ��� or at least a full Poetry Caf�� basement. Plath���s name came up in the course of an anecdote about the bad old days when, according to one poet of the 1960s, there were no women poets ��� ���there was only Sylvia Plath���.

���And then there wasn���t���, somebody quipped.

Some familiar questions followed ��� questions of narrow canonicity, poetry establishment values and so on ��� along with a mixture of hazy replies (is it sign of critical authority on modernism when somebody has to ask which was published first, ���The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock��� or The Waste Land?) and some more striking remarks. Berry recited a poem first published in the TLS, Astrid Alben���s ���One of the Guys���, a comic account of the terms on which a female poet could be accepted by her male peers, of whom a blotto representative appears in Alben's anecdote ("Are you turning, shurely not, feminissshht?"). Key recited an anaphoric list of demands in response to the recent BBC Poetry Season: ���I want a programme about Claudia Rankine . . .���.

It was also soon established how everybody in the room felt about Philip Larkin. Here Larkin was taken to be emblematic of that notoriously narrow, all but Leavisite canon, a figurehead for the perceived parochialism of the mainstream. (That���s just one way to read Larkin, mind; a realist reading that rejects the Hardy-like strangeness of Larkin���s best work.) Do you like Larkin���s poetry?, the audience was asked. Most hands went up. And do you believe Larkin to be ���culturally central��� for us now? Most hands stayed down.

That was an odd, revealing moment. Who were we to say that Larkin isn���t a crucial, culturally central figure any more? (A whole primetime BBC documentary says otherwise.) Or that a majority in that very room claiming to like Larkin could be anything other than an intimation of his cultural centrality? (Try it with a random group of poetry readers in relation to some of his talented contemporaries: Donald Davie, D. J. Enright, Elizabeth Jennings?)

On the other hand, neither Berry nor Key could claim that Larkin had been a crucial influence on their own work, as he has been for others, which seems perfectly fair enough. The appropriate T. S. Eliot dictum to quote here is from ���Tradition and the Individual Talent���: ���if the only form of tradition, of handing down, consisted in following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes, ���tradition��� should positively be discouraged���. The brief form is: each to her own.

What would have happened if Belinda Jack had conducted the same straw poll in relation to Plath, I wondered? Not that it had been the same sort of occasion ��� the anxious question of influence instead came up in the form of a reference to Harold Bloom. A lecture complete with recordings of Plath talking about her work, with that distinctive Yankee twang in her voice, and a couple of concisely close readings, it restored, for one thing, the ���extraordinarily suggestive, mesmerising, mysterious qualities��� of Plath���s late poem ���Sheep in Fog���. Jack was out to contradict Ted Hughes���s determinedly tragic biographical reading, a pessimistic tracing of a suicide-oriented trajectory from draft to draft. ���It is as though he has installed some monstrous, gigantic machine���, she noted, ���that has dispelled the fog and left the hills there . . . .���

The contradiction was welcome, although there's a lot more to say about Plath, the suicide narrative and other figures significant for the reception of her late work (see Justin Quinn's recent TLS review of The Alvarez Generation by William Wootten, for instance).

Lucidity is a verbal art, of course. It is not that a first glance must reveal nothing ��� only, as in the case of "Sheep in Fog", that time and re-reading will reveal more. ���Shakespeare is a difficult poet���, Roy Fuller asserted in one of his lectures as Oxford Professor of Poetry, ���but then all good English poets have been difficult (with a few exceptions!). The language is in favour of difficulty. . . .���

The Poetry Caf�� conversation continued. There was praise for older poets such as John Ashbery and Denise Riley, whom critics perhaps wrongly tend to assign a wintry role in their own cursus honorum, regardless of the sprightliness with which those poets might write. (Sprightliness, I admit, like feistiness, has its own potentially patronizing overtones.) Transatlantic comparisons were made, attitudes to gender queried. And isn���t the internet a jolly good thing, we could say, when distinctively independent-minded critics such as Charles Whalley and Dave Coates can speak out there? (I would add Charles Boyle; no female critics were suggested.) And then Katy Evans-Bush raised the issue of the digital gap ��� another form of having and having-not ��� and the uncertain future of a fluid medium that depends for its ongoing usefulness on an ���information wants to be free��� ethos.

All this put me in mind of the poet Gerry Cambridge���s observation (mentioned previously on this blog) about the internet upsetting the established ���power structures��� of contemporary poetry ��� ���the old hegemonies seem less significant than energy, imagination and new approaches��� ��� which he set against the ���unsensual��� ghastliness of ���on-screen reading���. The subject comes up again in the course of a symposium published in the magazine Cambridge edits, The Dark Horse: ���the Internet���, the American poet Abigail Deutsch acknowledges, ���makes a lot of poetry happening anywhere in the country available to anyone, anywhere���.

That sounds good. Yet that same symposium begins with the aunt sally assumption that British poetry is still beset by some version of the Movement-led ���gentility principle��� Alvarez inveighed against in the New Poetry anthology of 1962. Can that still be true in the ���anyone, anywhere��� age?

In The Dark Horse, Rory Waterman replies that it isn���t: ���British poetry is really a diverse and not always complementary set of poetries, with a diverse and not always complementary set of champions . . . complicated by Britain being a nation comprised of nations, with one huge and dominant city in its south-east corner���.

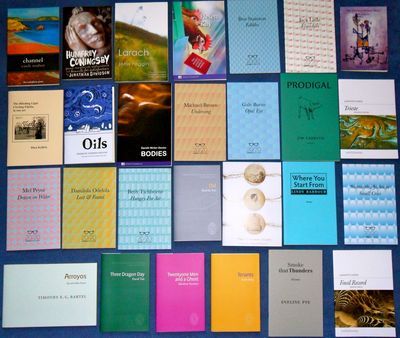

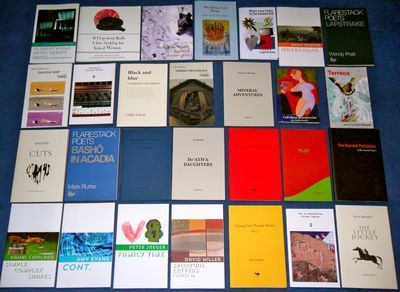

As one of this year's judges for the Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets, Waterman offers further testimony to that complexity and diversity in his survey of twenty-four poetry pamphlets from fifteen different small presses, including Clutag, Emma Press, Eyewear, Grey Suit and Shearsman, in the latest TLS. Whether pamphlets serve as a ���nursery slope for poets without a book���, a ���stop-gap for poets between books��� or simply a ���genre in its own right��� (which is how I prefer to see them), they give us plenty of evidence of that not always complementary diversity, a ���rich multifariousness���: the veteran Peter Riley���s ���ethereal, wide-ranging��� Ascent of Kinder Scout; Damilola Odelola with ���something to say about life and youth in our times���; Laurna Robertson���s ���pellucid yet complex��� collection inspired by her native Shetland; Eveline Pye���s ���startling��� vision of Zambia; and many more besides. The winners of the Michael Marks Awards will be announced at the British Library tomorrow evening.

Thursday: at the British Library, I find the poetry section of the bookshop. There are no surprises there at all ��� Plath, Larkin, Hughes, a marvellous but lucky few more. But so much more is out there, somewhere. And so much more is in the books you only think you���re finished with. Why not have a look for it? All of it.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers