Peter Stothard's Blog, page 18

October 26, 2015

Siri Hustvedt in London

By ROZ DINEEN

There was a full house on Friday night in Tavistock Square for Siri Hustvedt in conversation with Dr Johanna Hartmann. Many in the crowd had spent the day attending events that focused on Hustvedt���s work, including panel discussions about trauma narratives, authorship and gender ��� all elements of a conference hosted by Birkbeck University as part of the Bloomsbury Festival.

Hustvedt began the evening by reading from a forthcoming collection of essays ��� in particular from a ���200-page essay��� called ���The Delusions of Certainty���, which probes definitions of the mind. Hustvedt characteristically returns here to ���first questions���: ���is [the mind] different from the brain?���; ���am I my mind?"; does the body think? (First questions are important, she later said; "most scholarly life asks the 347th question, which is propped up by the 346 before"). The essay followed the arguments of Descartes, Hobbes and Margaret Cavendish, among others, but the effect was entirely modern.

In the discussion with Hartmann that followed, Hustvedt touched on topics such as "the third brain" (the placenta) and phantom pregnancies. She referred to Steven Pinker (whose books include How the Mind Works, 1997), more than once, as ���an irritant���. ���Specialized knowledge can be abused", she said, "especially when it is brought to you on a platter.��� The over-confident statements of Pinker et al can leave the impression that "all has been solved". There is never any suggestion in Hustvedt���s work of solutions; she opens up questions instead.

The questions from the audience were varied and interesting, reflecting the academic interest in Hustvedt's work as well as the enthusiasm her fiction attracts. A few wanted to know more about her creative process. This was harder to pin down even than the mind.

The TLS on Siri Hustvedt:

October 25, 2015

Agincourt 600

By DAVID HORSPOOL

On this day 600 years ago, a depleted invading army faced an outnumbering defensive force across a ploughed field in Normandy. The English invaders had lost some of their numbers to dysentery ��� the ���bloody flux��� ��� and had been forced to leave 1,200 of their comrades behind to garrison the devastated town they had managed to capture after an extended siege. A fourteen-day march through hostile country had led them eventually to this stretch of open ground bordered by woods, where they took up position and waited for the French army, filled with princes of the blood, to attack.

The young king in command of the English army, Henry V, had made one mistake already in keeping his troops too closely quartered together at the siege, allowing disease to spread freely. Perhaps his march had been another. He could have disembarked after the siege of Harfleur, but decided instead to make for Calais. He had barely managed to elude his pursuers as he attempted to cross the River Somme. Now he was relying on his opponents to make a mistake, the same mistake they had made in his predecessors��� day, of trusting that their cavalry could overwhelm English archers and dismounted men-at-arms. If all went to plan, the French would charge, the arrow shower would cut them down, and those who got through would be impaled on the wooden stakes that the King had ordered to be driven into the ground in front of the bowmen.

But the French had no intention of falling for that old trick. This time, they waited for the invaders to come to them, confident that in a hand-to-hand fight, their weight of numbers would tell. They may have taken some comfort from the fact that October 25 was the Feast of St Crispin and St Crispinian, brother saints who had worked for the conversion of the Gauls in the third century, and were buried at Soissons, in Picardy. This, surely, would be a day for the French.

What rarely comes across in accounts of Agincourt is that it was, initially, a very big game of chicken. And Henry V blinked first, or appeared to, at least. He was the first to advance. Unfortunately for the French, the advance was only a short one, before the English took up their static positions again, with archers at the front, still defended by stakes, ready to loose their deadly barrage. But it was enough to prompt a French response, a charge by their over-populated vanguard, and the same old story played out again: horses and men downed by English firepower; horses and men stuck in the sucking mud; horses and men piling on top of each other, the dead and the living, the latter unable to advance or retreat, easy prey for the English men-at-arms, even for the lightly armed archers.

There are still many debates about Agincourt, some of which emerge from the impressive new exhibition at the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London (which runs until January 31, with special family events for half term). How many fought on each side? What was Henry V���s original war aim? How much did his victory owe to luck rather than great leadership? Was the killing of prisoners towards the end of the battle a war crime? But the exhibition���s curators are surely right to concentrate first on the battle as an emblematic moment, an occasion that, whatever its strategic implications, proved inspirational to subsequent generations. This was a process that began shortly after the battle itself, as a manuscript copy on display from the Bodleian Library of the Agincourt Carol, written only days after news of the victory came back to England, attests.

To the French, of course, the legacy is rather different, if remembered at all. The exhibition, curated by Malcolm Mercer, curator of Tower History at the Royal Armouries Museum, with historical advice from Anne Curry, doyenne of Agincourt historians, is a bi-lingual affair, captioned throughout in English and French. If this is still the English (and British) view, it is one that pays much more than lip service to the French. We learn about the difficulties of the French political class, jostling to fill the power vacuum created by the madness of their king, Charles VI. We can compare conceptions of royal chivalry associated with the cult of St Denis on the French side and St George on the English, and marvel at the boy���s bacinet and mail shirt created for Charles as dauphin, or the exquisite ���dragon saddle��� of wood and bone made for Henry V.

Then there are the stories of the high-status French prisoners, who survived the battle to be ransomed, though the Duke of Orl��ans, Charles VI���s brother, had to wait twenty-five years for his freedom. He started and ended his captivity in the White Tower, but he was moved around the country, and an autograph letter on show at the exhibition from Henry confides the King���s fears that the Scots may attempt to spring the royal Duke from captivity in Pontefract Castle.

At the centre of the show, however, is a modern object that sums up the emotional pull that semi-legendary events like Agincourt achieve ��� once the bloody reality has faded from memory. It is a model diorama, with more than 4,000 painted tiny metal figures, displayed on a miniature re-creation of the battlefield that even includes soil from Normandy. Battle models have a distinguished if sometimes troubled history, re-enacting the debates of historians (and participants), as happened in the case of the Waterloo model made during the Duke of Wellington���s lifetime by Captain William Siborne. But they are also marvellous objects, which (is this a boy thing?) tend to bring out the child in the viewer (all right: in this viewer).

The Agincourt model is a thing of beauty, which gives an impression of the scope of the whole battle, while also making high-status individuals readily identifiable by their scrupulously reproduced heraldic symbols. But it is also a contribution to an argument. The model-makers, David Marshall and Alan and Michael Perry, told me that they took the advice of Professor Curry for nearly all their decisions about deployment, positioning and numbers. Having recently chaired a discussion of the battle at the London Lit Weekend at Kings Place, I know that Curry���s views are not unchallenged. Jonathan Sumption, the fourth volume of whose projected five-volume history of the Hundred Years War has recently been published (covering the Agincourt campaign), follows the literary evidence in arguing for a more traditional interpretation, that there were far fewer English soldiers than French. In following Curry, the model-makers present a rather more even contest than the myth-makers ��� Shakespeare chief among them ��� as well as some modern historians, would be prepared to concede.

To hear a recording of the discussion at the London Lit Weekend in full, where I spoke to Professor Curry, Lord Sumption and Dr Helen Castor (author of, among other things, Joan of Arc: A history) click here. It���s excellent preparation for a visit to this marvellous exhibition. The model, I am told, will go on permanent display after the Tower of London exhibition closes at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, but it is certainly worth seeing in context, to the accompaniment of the sounds of battle (recorded at a re-enactment) and beneath a ceiling of arrowheads, suspended menacingly above the room.

October 23, 2015

Why this Shakespeare chatter?

By MICHAEL CAINES

The novelist Kamila Shamsie suggested in the summer that 2018 could be a year of publishing only women ��� which I'd be very happy with, if her male counterparts could find alternative employment for a little while (it would do some of them a lot of good) ��� but first, please can we make 2017 a year of avoiding one particular long-dead male author?

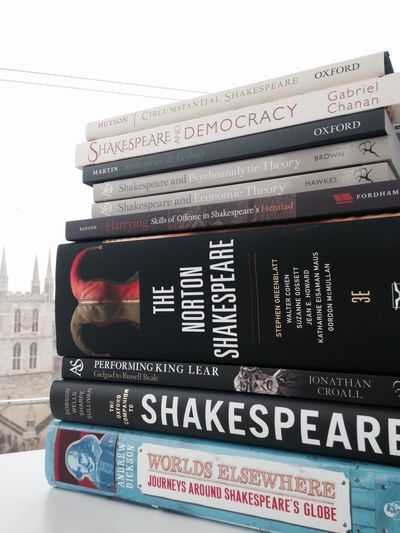

I recently participated in a debate at the Barbican, "Why Does Shakespeare Matter?", as part of the Battle of Ideas that Andrew Irwin has already written about on this blog. At the time, I had read only a little of the book at the bottom of the pile pictured above. (Take a moment to admire this paper monument, if you please ��� and note how Southwark Cathedral, which Shakespeare would have known well, is artfully dwarfed in the background.) Since the debate, for every few pages of progress I've made with Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys around Shakespeare's Globe (that slowness being no reflection on Andrew Dickson's writing, by the way; just on my current bear-of-little-brain state of mind), another Shakespeare book has arrived.

So here they are: new studies from Oxford University Press and Fordham University Press, Bloomsbury and Troubador; and dominating the lot, the Norton Shakespeare, now in its third edition. I'm about forty pages into Worlds Elsewhere and, assuming I read on at the current rate of progress, about 5,700 pages from the end of Circumstantial Shakespeare.

Of course, TLS HQ is full of books. Your humble paperbacks, your not-so-humble studies of Alice in Wonderland in three enormous volumes ��� they're all here. But this is a kind of flash flood; and I'm pretty sure, at least in terms of review copies submitted, that there is only one author who could have inspired it. (As a commissioning editor, I look out for such things, in case two or more books on the same theme, published around the same time, can be neatly reviewed together.)

Yet wasn't it merely a couple of weeks ago that the TLS led with John Kerrigan's review of 1606 by James Shapiro? Didn't we start the year with Shakespeare's heralds, Shakespeare on Capitol Hill and Shakespeare's Princes of Wales?

And isn't next year going to be the year for the World Shakespeare Congress, Shakespeare400, Shakespeare Oxford 2016 . . . you get the idea. Just say yes. Resistance is futile ��� not least as a new flood of new titles threatens. Mixing the serious with the frivolous and the downright fictional, all are to mark the 400th anniversary of the death of an upstart crow. Here's just a sample to whet your appetite or send you running for the Bard-less hills (be suspicious of any publisher who uses the B-word, of course):

The National Archives: Shakespeare unclassified; Shylock Is My Name by Howard Jacobson; I Love Shakespeare: 400 fantastic facts; The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation; Hamlet: Fold on fold; The One King Lear; Shakespeare's Yoga: How the Bard can deepen your practice ��� on and off the mat; Shakespeare and the Stars: The hidden astrological keys to understanding the world���s greatest playwright; How To Love: A biography of Shakespeare���s immortal Rosalind; 1616: Shakespeare and Tang Xianzu's China; Will's Words: How William Shakespeare changed the way you talk; A Smidgeon of Shakespeare: Brush up on the Bard with lists, facts and fun &c &c &c.

There. Did you spot the frivolous ones?

The debate itself, incidentally, was a much more interesting affair than I could have hoped for. All I'd come prepared to offer was a rather curmudgeonly, backwards-looking account of Shakespeare today as the product of innumerable acts of rewriting, suppressing, excising, fragmenting and wilfully misinterpreting ��� my own small contribution to the Shakespeare industry is, after all, a book that's largely about eighteenth-century acts of creative (or sometimes downright unimaginative) adaptation of Shakespeare.

Fortunately, there were others on the panel ��� notably Professor Kiernan Ryan ��� to point out the manifold possibilities in Shakespeare, the still (still!) as yet untapped potential. It was a forward-looking, hopeful message. I suppose you (meaning me) could see a flash flood of literary criticism as testament to that heartening idea ��� and be grateful for it.

(Although I still think it's really Marston400 in 2034 and the World Ben Jonson Congress in 2037 people should be holding on for.)

Out of the woods?

Little Red Riding Hood by Arthur Rackham

By ELIZABETH DEARNLEY

Behavioural advice given in fairy tales tends to be fairly clear-cut. Be kind, unselfish and willing to weave nettle coats for your eleven brothers, and you'll probably end up marrying a king. Be rude, greedy and reluctant to help a mysterious trio of men you meet in the woods, and you'll almost certainly start coughing up toads with every word you speak, before being rolled into a river in a nail-studded barrel. Sometimes, however, the intended moral of the story is a little more cryptic . . . .

In Fitcher's Bird, a Bluebeard-type story found in the Grimms' Children's and Household Tales, a beggar asks a beautiful girl for a piece of bread. After providing the bread, which both human compassion and fairy-tale convention suggest would be the right thing to do, the girl is then captured by the beggar (who turns out to be the wicked sorcerer Fitcher in disguise) and stuffed into his enchanted backpack. The wisest course of action, it seems, isn't always the obvious one.

The tempting, tangled forest of conflicting advice, life lessons and moral guidance given in fairy tales is recreated this weekend in Out of the Woods?, an interactive maze installation I've constructed with Liliana Ortega Garza in the Main Quad of University College London for the 2015 Bloomsbury Festival.

Based on Little Red Cap, Hansel and Gretel and other fairy tales set in forests recorded by the Grimms, the maze invites you to navigate your way through a woodland environment and create your own story. Each fork in the path presents you with a moral dilemma from a fairy tale. You choose which route to take by deciding what you want to happen next; it's like a Choose Your Own Adventure book you can walk around. Will you go directly to grandmother���s house? Will you look after Fitcher's egg? Will the choices you make allow you to escape the maze and leave the woods safely, or will you remain trapped for ever?

Out of the Woods? has grown out of my research at UCL's School of European Languages, Culture and Society ��� where I examine fairy tale-like narratives in different media, from medieval werewolf tales to the internet meme Slender Man, and the ways in which these stories can change (in terms of setting, character or ending, for example) with each new retelling ��� and Liliana's work in the Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, which focuses on people's perceptions of public spaces, and how the act of walking affects their emotional and physical sense of place.

Constructing a maze in the middle of a university has been a new ��� and frequently surreal ��� experience for both of us, whether we were figuring out precisely how to make large wood-and-cloth wall panels that also light up (with the help of the staff at UCL's Institute of Making), or sitting backstage at the Bloomsbury Theatre with a sound technician, trying to decide what type of goblin laugh would sound most satisfyingly eerie. Will people find the experience (as we intend them to) a convincingly immersive one ��� perhaps imagine, for a moment, that the witch might not be too far away . . . ? After all that intensive work behind the scenes it's hard for us to say. Why not come along and tell us?

Out of the Woods, Bloomsbury Festival: UCL Quad Pavilion, Saturday October 24: 12pm���7pm, Sunday October 25, 9am���7pm; Being Human: UCL South Cloisters, Friday November 13, Saturday November 14 and Sunday November 15, 9am���7pm.

Liliana and the Institute of Making technicians constructing the wall panels

October 21, 2015

Verlaine���s revolver

Revolver Lefaucheux �� Coll. Private

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Victor Hugo first visited Belgium, accompanied by his mistress Juliette Drouet, in 1837. He described the seventeenth-century baroque belfry in Mons as resembling a large coffeepot flanked by four smaller teapots. ���It would be ugly if it wasn���t grand���, he wrote to his wife Ad��le back in France.

The belfry, which looks down on cobbled streets and squares, is one of several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Wallonian region; nearby is the Grand-Hornu, an old mining complex (the region was a coal-mining centre until the 1980s), built between 1810 and 1830. That was designated a World Heritage Site in 2012 and now houses a Museum of Contemporary Arts.

Mons itself, forty minutes south of Brussels by train, is one of two European Capitals of Culture this year (the other is Pilsen, in the Czech Republic). Its mayor, the dapper Socialist Elio di Rupo, has been in office since 2001, though he took time out to be Prime Minister of the country from December 2011 (ending the country���s 541 rudderless days) until October 2014. His city appears to be thriving: a new railway station, designed by the star architect Santiago Calatrava, is under construction. Next to it is Daniel Libeskind���s recently completed Centre de Congr��s.

The city is also home to the quirky Mundaneum. Described as the ���web time forgot��� by the New York Times and the ���paper Google��� by Le Monde, it was set up in 1910 with the quixotic aim of ���gathering together all the world���s knowledge in one place��� by ���one of the fathers of bibliography���, Paul Otlet, and the Nobel Peace Prize-winner Henri La Fontaine. To the casual visitor it seems to consist of rows and rows of little wooden drawers containing card files, but underground there are also apparently 4 miles of documents, books, posters, postcards . . . .

The Mons Memorial Museum, a handsome former pumping station ��� all brick, glass and steel ��� was opened earlier this year too and should be required visiting for anyone undertaking a First World War pilgrimage to the region: Mons was the scene of the British Expeditionary Force���s first serious engagement, in August 1914 (think of the Angel of Mons), while the last British soldier to be killed, forty-year-old Private George Edwin Ellison, died on the outskirts of the town 90 minutes before the Armistice was signed. And as if that weren���t poignant enough, the Museum houses a plaque to the Canadian George Lawrence Price, who died at 10:58 am on November 11, 1918.

During the past fortnight four exhibitions have opened in and around Mons. First, in Charleroi, some 40 km away, yet another new museum, the BPS22, is staging the impressive Les Mondes Invers��s show until the end of January 2016, with works by Marina Abramovi��, Carsten H��ller and Yinka Shonibare among many other contemporary artists ��� vaut le d��tour.

"St George fighting the Dragon" by Tilman Riemenschneider (c.1460���1531) �� BKP Berlin

Meanwhile, the exhibition on St George and the Dragon at the Grand-Hornu (until January 17, 2016) brings together representations of the popular theme from the Renaissance onwards. There is an exquisite Reliquary (c.1467���71) commissioned from G��rard Loyet and on loan from Li��ge Cathedral. Made entirely of gold, silver and enamel, it represents Charles the Bold touchingly thanking George for his heroic deed. Elsewhere there are paintings by Altdorfer, Albrecht D��rer and Tintoretto ��� as well as some anonymous works. Bringing us up to date is David Claerbout���s mesmerizing twelve-minute film Travel (2013), which takes the viewer into and out of a forest charged with a sense of mystery and danger.

The BAM Mons in the centre of the town plays host to Parade sauvage, an exhibition of work by artists deemed to have been influenced by Rimbaud (���J���ai seul la cl�� de cette parade sauvage���), from Fernand L��ger, Asger Jorn, Joseph Beuys, Guy Debord and Robert Rauschenberg to Err��, Nancy Spero and others. One of the Beuys exhibits, the glass-cased ���Butter & Beeswax���, may present an olfactory challenge to the exhibition's curator, Denis Gielen, in weeks to come.

Undoubtedly the highlight of the exhibition openings is Verlaine Cellule 252: Turbulence po��tiques, also in the BAM (it drew Patti Smith on its first weekend). Its curator, Bernard Bousmanne, has brought together more than 200 items relating to the poet Paul Verlaine���s turbulent times in Belgium. It was in a hotel room in Brussels in July 1873 that he fired the two shots at Rimbaud, lightly wounding him in the wrist with the first of them. The revolver used (which is in private ownership) is displayed here for the first time ��� and it���s a beautiful object. Rimbaud (who was eighteen at the time) decided not to press charges, but the fierce judge Th��odore t���Serstevens nevertheless found plenty for which to convict Verlaine: involvement in the Commune, mistreatment of his wife, abandonment of his young child, alleged homosexual activity (although homosexuality was not illegal in Belgium), loose morals, inebriation. Verlaine was transferred after a few months from a prison in Brussels to one in Mons, where he spent a little over a year, and was reasonably treated (unlike Oscar Wilde in Reading Gaol some twenty years later): exempted from manual labour and permitted to write (quite a productive period). The prison, a few blocks away, is still in operation, and houses some 400 inmates.

The Verlaine exhibition will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

October 20, 2015

La mort du lecteur

A banner on the front of the New York Stock Exchange; �� Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty Images

By ANDREW IRWIN

Last weekend I went to the Barbican for this year���s Battle of Ideas ��� two days of ���high-level, thought-provoking public debate���. ���From Literature to Twitter: The death of the reader?��� was the vague title of one such discussion, but it was perhaps thanks to that vagueness that the debate proved fruitful.

Gathered around the table were Teresa Cremin, an Open University Professor of Education; Frank Furedi, the author and social commentator; Laurence Scott, a lecturer in English and writer on technology; and Sam Leith, the Spectator���s literary editor; with David Bowden of the Institute of Ideas as chair. The speakers seemed to respond to slightly different versions of the verb-free question. Scott focused on internet culture and the potential it has created for new literary forms. Furedi was troubled by the apparent infantilization of students, of whom increasingly less reading is ��� allegedly ��� demanded. Cremin convincingly discussed the limitations of an educational system that views reading in terms of proficiency benchmarks. When the arguments did overlap, however ��� and, crucially, conflict ��� there was a sense that this could be a productive dialogue.

Furedi argued, for example, that in a world where everyone with a Twitter account can consider himself both reader and writer, we lose something of the old value order that let us rate some literary works and some authors more highly than others. Leith responded that, far from there being a flattening-out of information, hierarchy is in fact intrinsic to the way we organize data on the internet ��� how would we ever find anything, if Google didn���t rank our results? ��� before later conceding that how things are ordered by Google���s indexing does not necessarily reflect literary importance.

Leith was perhaps the most optimistic about the current state of reading in the age of digital reproduction ��� and, to my mind, the most compelling. In his opening remarks, he declared that there simply is no crisis. Everything, in his estimation, is ���tickety-boo���. As people turn from television to the internet, they swap an essentially picture-based medium for an essentially textual one. It seems that we may be doing a lot more reading these days. If Twitter and hyperlinked-article hopping are killing our attention spans, he wondered, how is it that the novel is flourishing while sales of short stories languish? Television series such as The Wire also demonstrate that an appetite remains for complex, long-form narratives.

Scott, meanwhile, made the interesting case that Twitter, as well as muddying the clean divide that used to exist between author and reader, allows for a novel form of storytelling. There is a new place for silence and space in narrative. If a writer tells a story in 140-character flickers of information, we must work harder to fill in the gaps, to build up the picture, while remaining conscious of what is missing.

There was, it struck me, an unspoken premiss underlying the debate, one apparently accepted not only by the speakers but also by many of the audience members who posed questions: that reading matters. Should we care whether fewer people are doing it ��� and especially whether they are reading the canonical, ���important��� works? The speakers seemed tacitly to reject a ���health���-focused idea of its benefits, one that sees reading as carrots or kale for the mind ��� with Furedi explicitly condemning the language of medicalization that can enter the discourse. There seemed to be a general consensus that books were important because of the ���love��� of reading they can inspire. Yet if someone does not love reading, and if there is no ���health��� benefit to be gained, it���s difficult to know what to say to convince him or her that spending time reading about people who do not exist is a sensible thing to do. It���s hard to swallow Jeremy Bentham���s adage that pushpin is as good as poetry ��� but it���s also tricky to say why it���s not. It would have been fun to watch the debaters give it a go.

A review of Frank Furedi's book Power of Reading: Socrates to Twitter will appear in a future issue of the TLS.

October 13, 2015

Is this love? Marlon James wins the Man Booker Prize

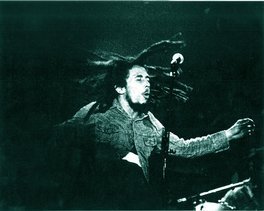

Bob Marley, The Hague. 1976

By ROZALIND DINEEN

Marlon James has won the Man Booker Prize with A Brief History of Seven Killings.

"It���s a sign of Marlon James���s unusual brilliance", said the TLS reviewer Paul Genders, "that a book so much about death is also teeming with life."

This novel, Genders said, provides a corrective to many fixed ideas about both criminal life and James���s homeland, Jamaica. The story ranges across two decades of Jamaica���s history and is told through several first-person accounts. The crime that sets off the seven killings of the title is an attack on "The Singer", a character based on Bob Marley.

Michael Wood, chair of the judges, said that the panel had come to a unanimous decision in less than two hours.

Our review of A Brief History of Seven Killings is available here.

TLS reviews of the other shortlisted titles are available below:

Tom McCarthy's Satin Island;

Chigozie Obioma's The Fishermen

A Spool of Blue Thread by Anne Tyler

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

And a review of Sunjeev Sahota's The Year of the Runaways is forthcoming.

October 12, 2015

Livres of the artists

By MICHAEL CAINES

It is often pointed out, but some people still manage to forget from time to time: a book is more than just its text. Text, in the sense of mere words on the page, is at the mercy of texture ��� binding, illustration, the quality of the paper against your hand, the individuality of the volume in question. For many mainstream publishers, it appears to be best to make books as uniform as possible, from their generic jacket designs onwards.

For artists, however, such material matters are opportunities to rig, say, a novel for novelty���s sake . . . .

Perhaps you've guessed it: I���m thinking of A Humument, Tom Phillips���s classic reworking of A Human Document (1892) by W. H. Mallock. A ���saggy and sanctimonious triple-decker���, as Gill Partington has observed, is here transformed into a rich work of art, ���as lewd as it is ludic���. It has run into several editions, and is now available as an app.

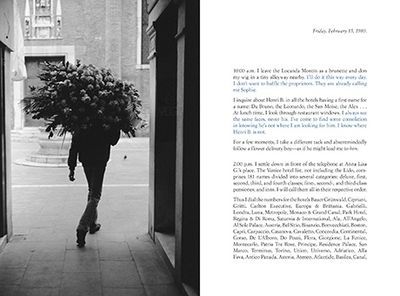

There's also the recently reissued Suite V��nitienne by Sophie Calle. Originally published in 1983, and now redesigned smartly in black and blue, this is the French artist's account of following a stranger around Venice, going through the motions of surreptitious desire, stalking him systematically yet also keeping an inner eye her own state of mind: "11:10am. After three hours of continuous comings and goings, I think I catch a glimpse of him. I start. It's not him". The facing page is taken up entirely, right to the edges, by one of Calle's many evocative photos of the disquieting city.

Recently I've been reading Unshelfmarked: Reconceiving the artists��� book. (Yes, that's where the apostrophe appears on the title page.) In this "para-library", constructed as an A to Z (ah, that old trick), Michael Hampton offers up a timely and unusual hymn to the history of artists, including Phillips, Ed Ruscha and Jeff Nuttall, mucking around with the narrow norms of book production.

Hampton is interested in what he calls the ���codex���s molecular structure��� ��� the book beyond its ���customary role as a vehicle for text���. It���s a deeper history than some might think. Unshelfmarked puts Firenze next to The First of April next to Les Grandes Heures de Rohan. In other words: the remains of a piece of controlled book destruction during a ���happening��� on the Charing Cross Road in 1967; a ���blank Poem, in commendation of the Suppos���d Author of a Poem Lately Publish���d, Call���d, Ridotto, or, Downfall of Masquerades���, a Shandean ���conceptual poem���, dedicated to ���No Body��� and consisting of isolated footnotes without the usual columns of couplets rising above them; and the fifteenth-century illuminated prayer book of exemplary Gothic lavishness that now resides in Paris, at the Biblioth��que Nationale.

There'll be a full review in the TLS in due course, so I'll just note for now that this must be a unique gathering for its juxtaposition of a Twitter feed (@urbanomicdotcom) with the "roguish promotional antics" of Edmund Curll and John Dunton (poor Dunton; doesn't he deserve more credit for his earlier achievements?) in the early eighteenth century, for bringing together the cryptographic Polygraphiae Libri Sex of Johannes Trithemius and the Punched Cards for the Analytical Engine, misleadingly attributed solely to Charles Babbage (poor Ada Lovelace . . .).

Unshelfmarked is a timely publication: I���m reading it ahead of two excellent opportunities in the coming weeks for prowling among rows and rows of books of this kind, in the form of All Tomorrow���s Publishers south of the river and then the tremendous Small Publishers��� Fair north of it. (Lucky Londoners, spoilt with such choice.) I���m going to try to attend both fairs ��� not least because I missed last month's London Art Book Fair at the Whitechapel Gallery and the ICA's earlier Room&Book ��� and guess that this post could be the first in a casual series of dispatches from the world of limited editions and artistic book experiments, over the same period. (We'll see. Neither Tangerine Press nor Test Centre, two different but entirely excellent independent London presses, seems to be turning up for either event.)

There���ll be plenty of conventional-looking books on show, of course ��� as well as readings and, at the Small Publishers Fair, an exhibition of the book works of Nancy Campbell (artist, writer, sometime TLS contributor). The main thing is that, for an old-fashioned materialist like me, in the Age of the Kindle, it���s a relief to find small publishers, fine presses and the like flourishing in the shadow of the Amazonian behemoth. I don���t know if the crowing over the tide turning against e-books is premature. At the other extreme, though, it doesn't seem inappropriate to borrow a word Hampton uses in the context of artists' books ��� "efflorescence".

October 9, 2015

Michel Tournier and the TLS

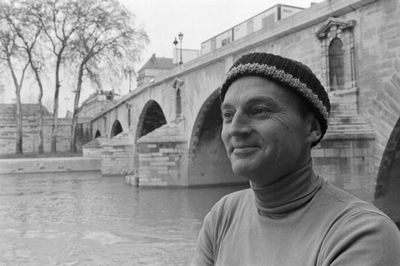

Michel Tournier, 1977 (Photo by Manuel Litran/Paris Match via Getty Images)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Yesterday���s awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature to the Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich wasn���t perhaps as much of a surprise as last year���s crowning of Patrick Modiano. It���s fair to say that the choice of Modiano put paid to any lingering prospects Modiano���s fellow Frenchman Michel Tournier may have had of being garlanded (and I���m not sure that he would care either way). After all, Tournier is ninety and hasn���t published a novel for nearly twenty years (��l��azar, 1996). It���s hard to imagine there will be another one.

Tournier hasn���t ever had his due in Britain: his novels were translated, and respectfully reviewed, but had little impact. His brand of intellectually probing novel of ideas is essentially alien to us, even if his first novel Friday (Vendredi ou les limbes du pacifique, 1967) is based on Robinson Crusoe. His great second novel Le Roi des aulnes (1970; The Erl-King) tackled the Nazi era in a way that was utterly strange and compelling. When his first collection of short stories Le Coq de bruy��re was published in 1978, the TLS reviewer Barbara Wright wrote ���M Tournier has a wide range of subjects, and of course he writes extremely well ��� but he still frightens me���,

I���m happy to say that there is something new from Tournier ��� not a novel, alas, but perhaps the next best thing. Recently published are his letters to his German translator Hellmut Waller, dating from 1967 to 1998, and therefore covering his entire career as a novelist; very interesting they are too (the book will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS).

Somewhat improbably, Tournier was, until recent years, a regular contributor to the TLS���s annual International Books of the Year feature in November. His short text, composed in French on a manual typewriter, would arrive by post with his calling card attached to it: ���Michel Tournier, de l���Acad��mie Goncourt���. It took me some years to realize that, in choosing a book of the year, he was drawing on his wide reading as a Goncourt prize judge; he would always opt for a book (usually by a young writer) that hadn���t won a prize but that he felt deserved being brought to wider attention. When, one year, his contribution included a joke that I didn���t find funny, I took the radical step of ringing him up and asking him if we could remove it ��� was this a wise course of action? He was taken aback: ���Vous ne trouvez pas ��a dr��le?��� There was no honest answer to that. The joke stayed in.

October 8, 2015

Same time next year?

Laurie Anderson, 2010; photo by Henry S. Dziekan III/Getty Images

By ROBERT POTTS

In Laurie Anderson���s extraordinary performance piece (or poem, perhaps?) ���Same Time Tomorrow���, she murmurs the following lines:

���And so when they say things like

���We're gonna do this by the book���,

you have to ask ���What book?���,

because it would make a big difference if it was

Dostoyevsky or just, you know,

Ivanhoe.���

I was reminded of ���Same Time Tomorrow��� by National Poetry Day, an annual event, when various media and institutions get excited about this beleaguered and much misunderstood art. Not the day itself ��� it's hard to be curmudgeonly about such a good-natured attempt to remind the nation of the power and pleasure of a literary genre ��� but the press release for it, a pro-forma piece of boosterism which linguistically offends against much of what it ostensibly values (���an opportunity to break with the tyranny of prose���). For we are all urged to ���Make like A Poet��� ��� to ���dream, speak, love, live, act and think ���like a poet������.

Of all the dangers currently or allegedly facing Britain, I cannot think of any greater than the possibility that people might actually take this advice. ���Drink like a poet���, for example; or ���drive like a poet���. But ��� and here���s where Anderson���s lines came to mind ��� it would really depend on which poet. After all, ���live like a poet��� these days would mostly mean that we���d all pitch up at a university and teach creative writing to each other; or else head straight to the university library to pen memoranda and furtively look at a cupboard full of pornography. As for ���love like a poet���, the racier biographies of poets testify to somewhat erratic love lives, the recent Life of Ted Hughes being only the latest example. And ���think like a poet���? As a colleague remarked yesterday, they surely don���t mean ���going on the radio to broadcast anti-Semitic propaganda���.

Flippancy aside, this gimmick ��� that we should all ���make like a poet��� for a day or so ��� does highlight a few truths about the perception and mediation of poetry in Britain. For example, the perception that there is something peculiar about poets; a sense sustained by the titillating biographical approach the media takes to them, since the simple, quiet acts of writing and reading are hardly externally dramatic, and certainly not easily conveyed by television or film ��� whereas tormented love lives and drunken fights are good box office material. Here the Romantic stereotype of the poet ��� a visionary, a rebel, whose bad behaviour is excused by soaring, inspirational art ��� seems to have been strikingly durable.

We are often told that other countries, more exotic than Britain, are unusually devoted to poetry ��� Salman Rushdie���s The Jaguar Smile, a paean to Nicaragua in the 1980s, quotes Jos�� Coronel Urtecho���s line that "Every Nicaraguan is a poet until proven otherwise"; Liz Calder, the co-founder of Bloomsbury, makes a similar claim for Brazil: ���In Brazil the word for poet is sometimes used as a term of endearment, as in ���How are you, my poet���, although the person addressed may never have written so much as a couplet���. By contrast, in England (it would be unfair to include the Scottish, Northern Irish and Welsh), poetry is regarded as a charming eccentricity, valued (as National Poetry Day shows), but scarcely central: after all, we���re encouraged to do this just for a day, for a bit of fun, like dancing round a Maypole or carving pumpkins into ghoulish faces.

So there is a tension between the poet as somehow special, meriting (these days) a month of programmes on BBC television and radio, and a nationwide celebration of excellence, and the contrary idea that we all could and should regard ourselves as poets. On the one hand, there is an egalitarian view, recently seen in the vision of the new Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn (���I think there is an artist in every one of us, there is a poet in every one of us���), a dream of creativity shared by, among many others, Charles Ives: ���The day will come when every man while digging his potatoes will breathe his own epics, his own symphonies (operas, if he likes it) . . .���. On the other, there are the ���closed shop��� arguments of the poet Don Paterson, in his 2004 lecture ���The Dark Art of Poetry���: ���Only plumbers can plumb, roofers roof and drummers drum; only poets can write poetry. Restoring the science of verse-making would restore our self-certainty in this matter, and naturally resurrect a guild that, I believe, would soon find it had some secrets worth preserving���.

What could it mean, then, ���make like a poet���? Perhaps it just means ���being ourselves���. But with even less money, and even more drink.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers