Peter Stothard's Blog, page 13

February 5, 2016

Jhumpa Lahiri���s writing Italian

Jhumpa Lahiri. Capri, Italy. June 2013. Photograph by Steve Bisgrove/Writer Pictures

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Conrad did it. Nabokov did it. As have, more recently, Milan Kundera, Andre�� Makine, Agota Kristof, Jonathan Littell. Now the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Jhumpa Lahiri has turned her hand to writing a book in a language that is not her first: Italian.

But there���s a difference. Force of circumstance was decisive in the case of most of the previously mentioned authors; Kristof (whom Lahiri briefly discusses), for example, fled Hungary in 1956 for Switzerland when she was twenty-one. The Franco-American Littell, meanwhile, grew up in both France and the USA and is completely bilingual (he won the Goncourt prize for his novel Les Bienveillantes, The Kindly Ones, in 2006). Lahiri, on the other hand, has been conducting an extended experiment with a language she fell in love with on her first visit to Italy in the 1990s. As a consequence she decided to move to Rome with her family in 2012.

She writes in her Author���s Note to In Other Words (Bloomsbury, ��16.99, to be published next week and reviewed in a forthcoming TLS): ���Apart from obligatory correspondence, I have written exclusively in Italian for more than two years now���. In altre parole (2015) has been translated into English by Ann Goldstein, best known now for her fine versions of Elena Ferrante's novels. The result is a dual-language edition (in the style of translated poetry) in which, in order to address the fact that Italian tends to be more ���wordy��� than English, the Italian has been set in fractionally smaller type than the English.

Lahiri has many pertinent things to say about reading in a foreign language, such as the confession that, tackling a novel by Alberto Moravia early on in her learning process, she had to ���underline almost every word on every page��� (we���ve all been there). She goes on: ���I find that reading in another language is more intimate, more intense than reading in English, because the language and I have been acquainted for only a short time���. She writes from a particular perspective: ���In America, when I was young, my parents always seemed to be in mourning for something. Now I understand: it must have been the language . . . . They couldn���t wait for a letter to arrive from Calcutta, written in Bengali��� (she has earlier revealed that she herself can���t read or write Bengali and speaks it imperfectly; her mother tongue, in other words, is ���a foreign language��� to her). Her mother, meanwhile, has continued to ���behave . . . as if she had never left India���.

When Lahiri points out that ���More than once [she���s] been confronted by a journalist or critic who maintains that I���ve written an autobiographical novel���, it prompts the thought: are writers who have been displaced from their original culture more likely to be the victims of such misapprehensions, as though they could somehow only write autobiographically? Maybe those journalists and critics were thrown by the frequent appearance of characters of Bengali origin in her wonderful fiction . . . .

Where will her Italian take Lahiri? She reveals at the end that she has ���to leave Rome this year and return to America. I have no desire to. I wish there were a way of staying in this country, in this language���. Maybe she���ll return.

February 4, 2016

Mail Rail

By DAVID HORSPOOL

Of all London's semi-secret underground curiosities ��� the Kingsway tram tunnel, the deep-level air raid shelters at Stockwell or Belsize Park, "ghost" tube stations from Aldwych to Down Street ��� the Post Office's 6-mile private subterranean railway running in a loop from Paddington to Whitechapel is perhaps the most intriguing. When the TLS's Freelance columnist Hugo Williams visited on a guided tour in 1998, the railway was still running, and he got to push the button sending a driverless "little red train" on its way from Mount Pleasant sorting office. But the Mail Rail was "mothballed" in 2003; this morning, I took up an invitation to Mount Pleasant to see the plans to incorporate it into the new Postal Museum, to be opened next year.

The division between the active business of sorting and delivering the post, and the contemplative project of memorializing 500 years of communication technology was much in evidence. When Hugo visited in 1998, there seemed to be no plans to stop using the Mail Rail. It was introduced in 1927 (after a sixteen-year gestation), I was told, because the streets above ground were so crowded, and the conventional Underground stations were not very close to the big sorting offices. The same conditions surely still apply a fortiori, but the little railway seems to have become too expensive in the new millennium. If you have ever wondered what mothballing means when used about large engineering projects, it turns out it means "left exactly as it was", �� la Miss Havisham, though with fewer cobwebs. The blurry photo below, for example, contains the roster sheet for what one assumes was the final shift at Mount Pleasant.

For entertainment between shifts, there was a dartboard, the sort you get in a pub, with doors and a little blackboard for the scores. But in a little over a year's time, when the Museum opens, the trains will run again. Visitors will be able to descend to the platforms (it is the only underground London railway apart from the Waterloo and City line which is all underground) and travel in a specially constructed replica carriage on a short loop, with digitally projected images to "enhance" their experience.

Above ground, a newly built museum will house postal curiosities, from a copy of Ulysses intercepted as an obscene book in 1932 to a sheet of Penny Blacks. But the highlight will surely be the Mail Rail. As we left the vast hall of the Sorting Office, apparently mistakenly being led past the thousands of wheeled postal cages (they are called "Yorks", I learned) and the great automated sorting machines, I hoped that, when the immersive Postal Museum opens in 2017, something of the ghostly ambience of the little railway (were those Christmas trees, complete with baubles, we spotted on the eastbound platform?) remains.

February 1, 2016

A tale of two play-readings

Roger Allam as Leonard in Theresa Rebeck's Seminar. Photograph: Alastair Muir

"Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts." I've had that line from the prologue to Henry V quoted at me twice in the past week. Once by Ian McKellen, at the launch of the BFI's Shakespeare on Film season, and a second time by Philip Wilson, the director of a staged reading on Thursday afternoon, at the Pleasance Theatre in north London ��� a staged reading that was also the premi��re of a Terence Rattigan play, Like Father, which has apparently languished unread since the 1960s . . . .

It's possibly a good time to be rediscovering Rattigan. Here's what John Stokes wrote in the TLS about Kenneth Branagh's recent revival of Harlequinade at the Garrick Theatre:

"Despite some mawkish tributes to the lovable 'madhouse' that is theatre . . . Harlequinade offers genuine theatrical enjoyment. It���s genuine because it feels authentic and because it is closely bound up with our sense of period. A once-lost playwright has been returned to us and he now looks indispensable, a truth-teller of the mid-twentieth century. Who would dare say that his status is undeserved?"

What a change that is. In his own lifetime, Rattigan had survived the cull of the playwrights that the Second World War very efficiently carried out on the side; the inter-war theatre world in which he'd made his name (with his Riviera farce, and first real hit, French without Tears in 1936) had gone, but still his plays were produced. The first production of The Deep Blue Sea (1952) ran for over a year in the West End. After that, however, came the crash, as Rattigan was compared unfavourably with the younger guns such as John Osborne and Harold Pinter. "Two superb craftsmen", he once noted of those two, by the way: "both writers of exceptionally well-made plays. They'd be annoyed if anyone suggested otherwise".

Like Father, the play I saw on Thursday afternoon, is one of the casualties of that grand falling-out-of-fashion: it seems that Rattigan put it aside in order to concentrate instead on Man and Boy (1963), about a ruthless financier and his socialist son. Like Father is a comic turning of those tables: the father, a hard-drinking Bloomsbury artist called Bert Leavensworth who is of the (Old) Left, the son Augustus (named for his artist-godfather . . .) who is frightfully bourgeois, and harbours no more horrific urge than his dream of one day qualifying as a chartered accountant. Like Father also bears a family resemblance to After the Dance (1939), in which the older folks are permanently sozzled, the younger lot strait-laced, and In Praise of Love (1973), featuring an Old Left dad and a Liberal Party son. One of Rattigan's gifts, though, is for seeing new and entertaining ways round such inter-generational differences. This unperformed play is like the Prodigal Son through the looking-glass, as Bert pours brandy after brandy, and Augustus tips his into the pot plants.

Only there are no pot plants, because this is a staged reading, after a morning's rehearsal. Roger Allam (pictured above not in Like Father itself but in similar mode) gives a characteristically assured, irascible turn as Bert ��� I've never heard such disdain for the world beyond central London packed into the aspiratory moment before somebody unwillingly pronounces the word "Horsham". Now I've seen the version with him and the rest of the cast ��� Heather Craney as his ex-stripper girlfriend (whose good heart makes a contrast to the snobbish portrayal of the financier's ex-chorus girl and gold-digger in Man and Boy), Emily Barber, Suzanne Burden, James Holmes, Luke Newberry and Rupert Vansittart. I have to list them; it was a historic performance, surely? And now I've seen the "Piece out our imperfections . . ." version, I'd like to see a producer boldly take this into the West End, where Rattigan belongs.

I confess: I do like a play-reading. There was one at Dr Johnson's house last Sunday, in fact. Directed by Lois Potter, our not-so-professional troupe also had a play to rescue from obscurity ��� Irene by Dr Johnson himself.

Unlike Rattigan, Johnson can boast no great history of theatrical success, survival and going out of fashion. He began writing Irene around 1726, I'm told, basing it loosely on an episode in Richard Knolles's General History of the Turks (1603). It wasn't performed until 1749, when Johnson's former pupil David Garrick staged it at Drury Lane with an excellent cast, magnificent sets and costumes, and plenty of variety in the way of entertainments around Johnson's tragedy, to keep the punters coming. It lasted nine days, which isn't bad going at all for the period (and would have meant Johnson was paid a few times over, I guess, on the author's "benefit nights"). I'd read it and seen extracts with some of the same cast performed to general amusement at Johnson's old Oxford college, Pembroke, at a conference last year. This time round, we performed the whole play, for a very indulgent audience, and tried to play it seriously.

It tells, after all, of Constantinople occupied by the Turks in 1453; the Emperor Mahomet falls in love with the Irene of the title and tempts her into ditching her Christian faith with the prospect of ruling the world alongside him. She takes it all quite well, really:

"Can Mahomet's imperial hand descend

To clasp a slave? or can a soul, like mine,

Unus'd to pow'r, and form'd for humbler scenes,

Support the splendid miseries of greatness?"

Of course, things don't turn out so well for our apostate heroine; she is led off at the end to be strangled by two murderous mutes. (I know because I played one of them.)

The thing is, without wishing to kid anyone about our Roger Allam-like acting skills, it all appeared to be going so well, and the more so because there were some good actors in the cast whom you could, you know, take your cue from. We felt we'd done Johnson proud. But at the end, as the audience politely applauded, and the company prepared to disperse, one of the actors said with conviction, and not especially sotto voce: "Never again!"

That was the biggest laugh of the night.

January 29, 2016

A glittering Korea

By TOBY LICHTIG

North Korea sells. If the books table at the TLS is anything to go by, we have a seemingly insatiable appetite for publications about the Hermit Kingdom and the antics of its eccentrically murderous ruling dynasty. But away from the escapee memoirs, famine histories and book-length speculations about the robustness, politically and gastrointestinally, of the youthful Dear Leader, it is the South that has been gaining headway in the more refined literary arts.

Over the past few years there has been a glut of fiction in translation arriving from South Korea, much of it critically acclaimed and some of it even commercially successful. This is partly thanks to the indefatigable Dalkey Archive, whose Library of Korean Literature, produced in collaboration with the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, will ��� when complete ��� amount to an impressive twenty-five novels and collections of short stories. The latest batch arrived on my desk last month: it includes a collection about the effects of capitalist materiality on the family unit (no doubt Mr Kim would have something to say about that); a mythical love story which explores desire and sexuality ���in all its ugliness���; and, yes, a defector tale about an escapee from a country ���that might be North Korea���.

In 2014, Mark Morris reviewed the first batch of Dalkey books for us and commended the publisher for promoting classics from the past century along with ���the work of younger writers who are less concerned with Korea���s past, its complex social fabric, and literary realism���. Last year, Claire Hazelton reviewed another Dalkey offering, Choi In-hun���s The Square, which she described as ���a cornerstone of Korean literary modernism���. Other recent successes from the region include Drifting House (2012) by Krys Lee and Please Look After Mother (2011) by Kyung-sook Shin, a novel about a disappearing mother which our reviewer, Kelly Falconer, described as ���captivating���, ���unsentimental��� and ���brutally well observed���. Kyung-sook���s book was a winner of the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2012 and, as Morris noted, perhaps more importantly in terms of sales, an Oprah Winfrey ���Books to Watch��� choice. Writing in the TLS in the same year, Margaret Drabble was similarly impressed with Pak Kyung-ni���s epic romance, Land: ���a remarkable and important work in which Eastern and Western traditions fruitfully meet���.

In her review Drabble reserved especial praise for Pak���s translator Agnita Tennant, whom she likened to the great Constance Garnett in her ability to open up a ���new territory���. Since then that territory has become increasingly well traversed. Choosing to translate from the Korean might have seemed like a precarious career choice a few years ago but the market has opened up. And while most of Korean literature���s international success stories have emerged from America ��� with its sizeable Korean community ��� Britain now has a success story of its own.

Deborah Smith is described by the Arts Foundation as ���the sole translator of Korean literature in the UK���. I find this claim somewhat hard to believe, but Smith is certainly our most prominent translator from the Korean. Last year, she brought into English Han Kang���s novel The Vegetarian, an unsettling tale about an escape from social stricture involving a woman who at first refuses to eat meat and then to eat food altogether. The novel went on to achieve something of a cult following. (This paper���s critic, Peter Brown, described it as ���a strange and ethereal fable, rendered stranger still by the cool precision of the prose���.) Smith has also just finished translating Han���s next novel, Human Acts, which looks at the gruesome repercussions of the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, in which the South Korean army massacred hundreds of anti-government demonstrators. Kate Webb will be reviewing this novel in a future edition of the TLS. Without wishing to spoil the surprise, she is very impressed, and has singled out Smith for the ���sensitivity��� of her translation.

Last night Smith received rather wider recognition for her efforts with the Arts Foundation���s Award for Literary Translation. Each year the Foundation provides six ��10,000 bursaries ���to be used to pay for living and working expenses���. This is only the second time a prize for translation has been included: the Foundation was launched in the early 1990s on the back of an anonymous ��1 million bequest with a remit to ���support the individual artist��� and the categories change each year. (The others this time were Art in Urban Space; Children���s Theatre; Jewellery Design; Materials Innovation; and Producers of Live Music.) Speaking of the choice to honour a translator, one of the judges, Amanda Hopkinson, highlighted the ���significance of cultural exchange��� and praised a sector that has been ���transformed��� in Britain over the past fifteen years. Receiving the award, Smith said she planned to use the money to fund research into the Korean author Yi Chong-jun, who died in 2008 leaving a corpus of thirteen novels and many short stories.

So congratulations to Smith and congratulations to the art of translation and congratulations to Korean literature, which once again seems to be enjoying its place in the sun.

January 28, 2016

Luton�� or Lut��n?

Kingsland High Street ��� Photo by David Horspool

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Luton Airport, once immortalized in song by Lorraine Chase (apologies for the earworm) has recently had a lift in the form of an advertising campaign for easyJet (see above).

I���m a big fan of easyJet; I particularly appreciate its choice of cheap flights to hitherto inaccessible destinations on the Continent. But I can���t help feeling that something has gone wrong with the poster ad: ���L��ton��� (German) and Lut��n (Portuguese) are fine, but Luton��? (Or is it intended as a distant echo of the French alcoholic drink Dubonnet, which itself was the subject of a famous advertising campaign once?) I think they would have done better to go for Italian L��ton or Spanish Lut��n ��� both countries well represented on easyJet���s flight network after all. And you can imagine Spanish passengers arriving at Lut��n.

There���s a well-known, socially engaged sandwich chain with a French name. It eschews the necessary accents, but as its name is entirely in upper case that���s perhaps understandable. �� and �� can look awkward after all.

On the other hand, I���ve always been irritated by the high street bakery Delice de France. If you���re going to be pretentious then don���t forget to put an accent in the right place, otherwise the temptation is to pronounce it ���deliche���, Italian-style. So that should be D��lice de France. But, according to the website bakeryinfo.co.uk, they���re about to change their name to Coup de Pates.

January 27, 2016

Emma���s readers (and rereaders)

"Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich . . .". In the latest episode of TLS Voices (see below) we draw out the bicentennial celebrations for Jane Austen's Emma. As a forthcoming review in the TLS notes, the novel first appeared in print on December 23, 1815, after being advertised as published "this day" a week earlier; its title page, as above, is dated 1816, as was conventional for books published so late in the year. Walter Scott's perceptive review of it appeared in the Quarterly Review for October 1815, which seems to have actually appeared in March 1816. Within another few months, a few more reviews came out; they were generally kind, but hardly the stuff of literary legend . . . .

This lukewarm initial reception perhaps only goes to confirm the view that Austen, who was herself a great rereader of novels, is a novelist whose books become better appreciated, both collectively and by the individual reader, as they are reread. This mattered greatly, as the editors of the Cambridge edition of Emma point out, at a time when novels might be generally regarded as disposable: "Readable books could be borrowed from the circulating libraries, only rereadable books need be purchased". What could matter more to a writer struggling for money working in a genre struggling for respectability?

That said, Scott saw much in Emma to enjoy on first acquaintance, but he was already interested in her work ("The author is already known to the public by the two novels announced in her title-page") and would certainly go on to reread Pride and Prejudice, "for the third time at least", with great pleasure in the author's "exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting". His review of Emma suggests how it struck him as being representative of a whole new stage in the evolution of the novel:

". . . a style of novel has arisen, within the last fifteen or twenty years, differing from the former in the points upon which the interest hinges; neither alarming our credulity nor amusing our imagination by wild variety of incident, or by those pictures of romantic affection and sensibility, which were formerly as certain attributes of fictitious characters as they are of rare occurrence among those who actually live and die. The substitute for these excitements, which had lost much of their poignancy by the repeated and injudicious use of them, was the art of copying from nature as she really exists in the common walks of life, and presenting to the reader, instead of the splendid scenes of an imaginary world, a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him. . . ."

(I hope this means, incidentally, that Scott knew people in real life who resembled the plain-speaking Knightley brothers, the pretty vacant Harriet Smith and Mr Woodhouse, "a valetudinarian all his life": "Mrs Bates, let me propose your venturing on one of these eggs. An egg boiled very soft is not unwholesome. Serle understands boiling an egg better than any body. I would not recommend an egg boiled by any body else . . .")

"We, therefore, bestow no mean compliment upon the author of Emma, when we say that, keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life, she has produced sketches of such spirit and originality, that we never miss the excitation which depends upon a narrative of uncommon events, arising from the consideration of minds, manners and sentiments, greatly above our own. In this class she stands almost alone; for the scenes of Miss Edgeworth are laid in higher life, varied by more romantic incident, and by her remarkable power of embodying and illustrating national character. But the author of Emma confines herself chiefly to the middling classes of society; her most distinguished characters do not rise greatly above well-bred country gentlemen and ladies; and those which are sketched with most originality and precision, belong to a class rather below that standard. The narrative of all her novels is composed of such common occurrences as may have fallen under the observation of most folks; and her dramatis personae conduct themselves upon the motives and principles which the readers may recognize as ruling their own and that of most of their acquaintances . . . ."

At that stage, of course, 200 years ago, no reviewer could know that the author of Pride and Prejudice (which is soon to be unleashed in zombie form at the cinema) was also the author of Northanger Abbey and three youthful volumes of skits and pastiches. Between them, those early works show how Austen's own imagination was highly amused by the wild variety of romantic fiction. Instead, in her hands, and at the level of the story itself, the new style of novel acknowledged by Scott seems to involve reaching a fundamental accommodation between romantic "excitements" and the "common walks of life". Catherine Morland is said to be seventeen years old and all too fully immersed in a Gothic world view; Emma Woodhouse is three years older but not much wiser. She sees her situation as being completely, contentedly settled, with no prospect of marriage taking her away from her father's house. The "unperceived" danger, if it can even be called that, lurks within her, a heroine nicely described by Emily Auerbach as a "woman with artistic capability but no sense of higher purpose or appropriate field for her powers" who is liable to mix up trivia with more important matters, and who regards matchmaking as "the greatest amusement in the world".

Its publisher John Murray appears to have had high hopes for Emma, since he gave it a first run of 2,000 copies, over 1,000 copies more than was normal. (The Antiquary by Scott himself, published in 1816, sold out a run of 6,000 copies in a few weeks; see Kathryn Sutherland's essay in the fifth volume of The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain for more such business-like details.) Yet more than 500 copies remained unsold in 1820, and were remaindered. Austen herself saw relatively little profit from the book; part of the deal was that she had to pay production costs, including advertising in Murray's own catalogues. Hence perhaps her famous comment on him, from October 1816: "He is a rogue of course, but a civil one". The rogue had asked Scott to review Emma, it's true, but without much enthusiasm: "It wants incident and romance, does it not?"

Perhaps he should have reread it.

January 22, 2016

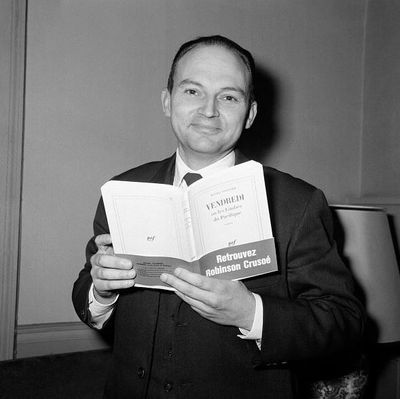

Michel Tournier RIP

Michel Tournier, 1967 (Photo by Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Michel Tournier, who died on January 18 aged ninety-one, twice failed his agr��gation in philosophy. This put paid to a career in France���s higher education establishment. He was wont to say that had he passed the exam he would never have written his novels. Three cheers for failure!

In his autobiography Le Li��vre de Patagonie (2009; The Patagonian Hare, translated by Frank Wynne), the filmmaker Claude Lanzmann talks of how, in 1946, Tournier persuaded him to join him in studying philosophy at the University of T��bingen in the French occupied zone of Germany. Tournier writes in his own intellectual autobiography Le Vent Paraclet (1977; The Wind Spirit) of how the small university town was, miraculously, completely spared the destruction wrought by the war (having gone there for three weeks, Tournier stayed for four years; Lanzmann, meanwhile, moved on to Berlin, where he was to teach at the Freie Universit��t, which he described as a ���den of Nazis��� at the time). In T��bingen, French students were entitled to a grant and sixty meals per month in the Maison de France, as well as accommodation. As Lanzmann writes, ���Germany was for [Tournier], as it was for us, the country of philosophy and we never envisaged its banishment��� from the community of nations.

Lanzmann goes on: ���But it was with the future author of Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique [Friday, or the Other Island], Le Roi des aulnes [The Erl-King] and Les M��t��ores [Gemini] that I spent most of my free time. Tournier was from a family of German scholars, spoke the language fluently and, as a child, had spent time in Hitler���s Germany. He rode and encouraged me to go with him. There was a military riding school in T��bingen run by a Colonel Whitechurch. I joined up, and, under the tutelage of a former Wehrmacht instructor continually barking insults and orders, I learned to perform riding figures, to ride bareback, to dismount a horse at full gallop . . . ".

Tournier, a Germanophile, boasted that he was probably the ���only French person to possess the complete works of Kant in German���, which he had bought in Paris during the Occupation. He translated Erich Maria Remarque, among other German authors.

We learn from Lanzmann that there were two sides to the essentially private Tournier: he had ���a jovial, hail-fellow-well-met, barrack-room buddy side; he was succinct and clear-thinking, but would suddenly, without warning, become absent, swallowed up by who knew what abyss. This was a different Tournier, one prey to bouts of bleak isolation that could last for hours or days, though it was probably in this crucible that the malign reversals of the dark, dizzying masterpieces he would write one day were forged���.

The first of those ���dizzying masterpieces���, Vendredi (1967), appeared when the author was forty-three. His output wasn���t vast ��� there were nine novels (arguably two of them masterpieces), a handful of stories and a few essays. But he was involved in other activities: as a judge for the Goncourt prize for many years; co-running a photography gallery in Arles; travelling widely. Having successfully reworked Vendredi as a book for a young readership, he also spent a lot of time visiting schools and preaching the wonder of fiction.

I commented in an earlier post that I sensed Tournier hadn���t really had his due in Britain. Slightly confirming my suspicions is the fact that no obituary (apart from one online in the Guardian) has appeared here yet. This strikes me as an oversight.

January 20, 2016

The Humans on Broadway

By CATHERINE HIGGINS-MOORE

On January 23, the glitzy musicals and tourist-attracting shows on Broadway will have to share a little of their spotlight with the little play that could. Stephen Karam's The Humans will transfer from the Laura Pels to the Helen Hayes Theater. Although the Helen Hayes Theater houses 597 and the Laura Pels seats 424, the cachet of moving to Broadway overshadows the reality that the theatres are not all that different in size.

Critics and audiences have slated Al Pacino in the new play by David Mamet, China Doll, and Keira Knightley received only moderate praise for her turn in Th��r��se Raquin, but no doubt the cast and crew of The Humans hold much hope that this play, powerful in its apparent ordinariness, will attract audiences who haven���t come to the theatre hoping to take celebrity selfies after curtain at the stage door.

While Deadline Hollywood called the off-Broadway production ���exciting theater��� and The Hollywood Reporter decreed it ���tremendously moving���, a number of publications, including New York Magazine, have gone so far as to pronounce it ���the best play of the year���.

Staged by Joe Mantello, whose previous directing credits include Wicked, The Last Ship and Other Desert Cities, The Humans will retain its off-Broadway cast for the move. The actors include the Tony nominee Reed Birney, The Good Wife���s Sarah Steele, Arian Moayed, Jayne Houdyshell, Lauren Klein and Cassie Beck.

The Blakes, an Irish-American family, have come together to celebrate Thanksgiving in the youngest daughter Brigid���s new Lower East Side apartment, breaking the tradition of celebrating in the family home in Pennsylvania. A struggling artist, Brigid has moved in with her boyfriend, an older man from a wealthy background. Cue awkward dinner-table conversations, and revelations precipitated by the alcohol and claustrophobic atmosphere. Lights go out and intimate moments are interrupted by mysterious bangs from an upstairs neighbour. Momo, the frail grandmother, has sporadic moments of lucidity, and Erik dreams about a faceless woman; these elements bring an otherworldly quality, layering something unexpected on to Karam's emotional kitchen-sink drama.

Karam���s writing is intelligent in its seeming simplicity, and the script is filled with poignant observations. Erik advises his daughter���s boyfriend:

"I���ll tell you, Rich, save your money now . . . . I thought I���d be settled by my age, you know, but man, it never ends . . . mortgage, car payments, internet, our dishwasher just gave out. Don���tcha think it should cost less to be alive?���

The dialogue is perfectly balanced light and shade. There is sibling banter and parental nagging but also clipped conversations that reflect warring perspectives on religion ��� and which dare to touch on this family���s taboos: dementia, debt, chronic illness, unemployment and 9/11.

The New York Times called Karam ���a mature writer, very much in command of his gifts���. The widespread praise Karam has received in his latest outing is unsurprising given that he was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2012, the same year he won the Drama Critics Circle award for his last play, Sons of the Prophet. There was talk of that production moving to Broadway, but the move never came to pass, so this must be a particularly sweet moment for the young writer, who has a long-standing relationship with Roundabout Theatre Company (RTC).

RTC produced both shows off-Broadway, and it was their artistic director Todd Haimes who secured Scott Rudin as producer for this Broadway run. Haimes said of Rudin, when speaking to Deadline: ���I wanted someone who was both a fine producer and was willing to commit both financially and emotionally to moving the production before the reviews came out���. Karam is now set to join the world of film heavy-hitters that Rudin dominates, not only because the powerful producer is backing his play, but because Karam has adapted The Seagull for film with a cast that includes Annette Bening, Elisabeth Moss and Saoirse Ronan.

January 18, 2016

A straw Powell

Some are born to it, some achieve it, and some . . . you know what I'm talking about, of course: greatness. Whatever the Dickens that is.

Literary greatness does not necessarily apply to the author whose books you enjoy most. Or whose books induce the worthy aching in the brain that lead their readers to boast about having finished them on social media.

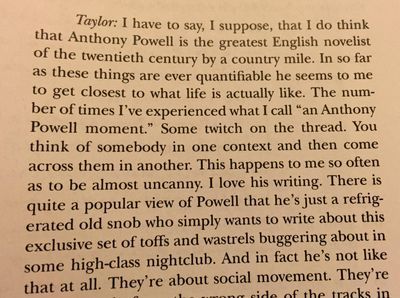

In any case, when one TLS contributor, Jonathan Barnes, interviewed another, D. J. Taylor, for the Dictionary of Literary Biography series, Taylor, the author of the recently published The Prose Factory, offered this intriguing answer:

It's an interesting choice, not least because, as Taylor suggests towards the end of this passage, Powell does not seem to be especially fashionable at the moment, for the dreary reason that he may seem to some to be merely a snob. (Find me the writer who isn't on some level a snob, in the Thackerayan sense of the word.) Awareness about class, the little differences and dramas that arise from it, is surely too English a trait to be denied to a novelist (who is, in any case, meant to notice everything).

Then there's that suggestion about one thing novels can or should do: get as close as they can to describing what life is actually like. My personal pantheon (you don't have one, too?) contains few writers who do this, I suspect. Or at least they don't do it as directly as Powell does, creating that distinctive sensation of a twitch on the thread.

Lastly, I had to ask around the TLS office to see if any current editor here shares Taylor's high opinion of one of their most accomplished predecessors. (Powell worked part-time for the TLS and reviewed for the paper in a reliably splendid style for decades.)

Nobody did.

Instead, I was mischievously offered, as greatest English novelist of the twentieth century, J. R. R. Tolkien; then Nancy Mitford as "most enjoyable". Another card nominated . . . our former colleague Giles Foden. (Sorry, Giles.)

At last, after some longing looks at the wide open vistas towards Europe, Ireland and the Americas, we got down to indigenous brass tacks: D. H. Lawrence ("You Leavisite . . ."), Evelyn Waugh, Virginia Woolf ("doesn't she still owe us some copy?"), Anthony Burgess, E. M. Forster ("Nothing to put next to Sholokhov, of course, but . . ."), Iris Murdoch. The Scottish contingent hankered after Muriel Spark ("she only once set a novel north of the border"). The fiction editor digressed to point out that Conrad had written what she thought was the best English story of the last century (and no, it's not in the recent Penguin anthology edited by Philip Hensher).

And so the discussion veered off in various directions, dispersing away from one kind of greatness to another, separated by country miles . . . .

January 16, 2016

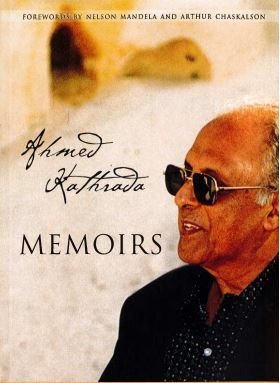

Ahmed Kathrada on Robben Island

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In June 1964 Nelson Mandela and seven fellow political prisoners were sent to Robben Island to begin life sentences. At what became known as the Rivonia Trial, in Pretoria, Mandela and his co-defendants were found guilty of sabotage and conspiracy to violently overthrow the government. (It was at this trial that Mandela made his famous lengthy peroration from the dock, concluding that the ���ideal of a democratic and free society��� is one ���for which I am prepared to die���.)

Mandela spent eighteen years on Robben Island. In March 1982, he and three other prisoners (including Walter Sisulu) were given thirty minutes to pack their belongings and transferred to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town. And in October 1988, in anticipation of his release, Mandela was moved again, this time to relatively comfortable quarters at the Victor Verster Prison in Paarl, some 60 km north-east of Cape Town. When he was released on February 11, 1990, in front of the world���s TV cameras, it was from the prison in Paarl that he emerged accompanied by Winnie Mandela, one fist raised in defiance (two would have suggested premature triumph, Mandela later explained).

Among Mandela���s fellow inmates was Ahmed Kathrada (���Kathy���), eleven years his junior. His fascinating Memoirs (published in 2004) deserve to be better known. Kathrada, of Indian parentage, was, in Mandela���s words, a ���key member of the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress���. In a foreword to the book, Mandela writes: ���Ahmed Kathrada has been so much part of my life over such a long period that it is inconceivable that I could allow him to write his memoirs without me contributing something, even if only through a brief foreword���. In the Acknowledgements to his own autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela had written: ���Thanks again to my comrade Ahmed Kathrada for the long hours spent revising, correcting and giving accuracy to the story���. Of his first meeting with Kathrada, Mandela remembers, ���Although I disagreed with [him], I admired his fire���.

Ahmed Kathrada arguing with the police; from his Memoirs

Kathrada vividly describes their arrival on the bleak, largely treeless island off Cape Town (June being a winter month in the southern hemisphere): ���We exited the aircraft to an icy drizzle and buffeting winds, to be met by guards armed with automatic weapons���. Later he says, ���If I had to use a single word to define life on Robben Island, it would be ���cold���. Cold food, cold showers, cold winters, cold wind coming in off the sea, cold warders . . .���. When not toiling in the lime quarry, the eight men were kept separate from other, lower-ranking political prisoners. Section B, built specially for the new arrivals, consisted entirely of single cells, whereas the other prisoners were more likely to be housed in dormitories.

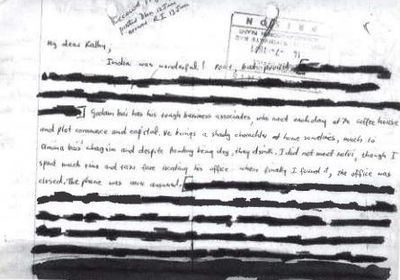

There were many acts of cruelty or spite. Kathrada reveals that letters of condolence to friends didn���t always reach their intended recipients; equally those written in languages unfamiliar to the poorly educated Afrikaner jailers went undelivered. Incoming letters were censored. Kathrada describes how a letter from his brother was withheld (he received it eighteen years later) because of its reference to ���a change of government in Britain. Harold Wilson and the Labour Party were now in power . . .���. Those dangerous Communists!

A censored letter addressed to "Kathy" Kathrada; from Memoirs

Photographs of Kathrada���s white girlfriend Sylvia were destroyed in front of him, as ���symbols of racial defiance���. No newspapers, radios, clocks or wristwatches were permitted (���warders deliberately concealed the dials of their own watches lest, perchance, we note the time of day���!). When the men once clandestinely acquired a transistor they had to go to baroque lengths to conceal it, and when the batteries ran down, there was no way of replacing them. Kathrada says that ���depriving us, through the long years behind bars, of access to news was one of the cruellest forms of punishment our jailers could inflict on us���. Yet he had two ���faithful literary companions��� with him in his cell: the Oxford Book of English Verse and the Complete Works of William Shakespeare.

And the prisoners formed debating and study groups (educating illiterate common criminals and the Afrikaner guards); at one point they discussed whether there had ever been tigers in Africa, Mandela pointing out that there was a word in ���isiXhosa for tiger, differentiating the animal from other cats���. Kathrada, meanwhile, persuaded Mandela to start (secretly) writing his memoirs. When he was also transferred to Pollsmoor, in October 1982, he reflected: ���Strange as it may seem, I missed the island ��� not the prison or the pettiness of the warders, but the ���family��� we had formed in B Section, and the setting���.

He writes of his liberation, ���I came out of prison at the age of sixty, having spent almost half of my adult life behind bars���. Elsewhere he tells us that ���In prison the minutes can seem like years, but the years go by like minutes���, an observation that speaks powerfully of tedium and loss. And yet he appears entirely without self-pity: ���From the moment I became involved in politics as a schoolboy, I realised that, unacceptable as my own circumstances were, the lot of my African colleagues and leaders ��� Mandela, Tutu, Sisulu, Tambo, [Govan] Mbeki ��� who would become household names, was infinitely worse���. He reserves his bitterness and rage for the brutal treatment handed out to associates: ���Suliman Saloojee, my dearest friend Babla, . . . brutally interrogated and tortured to death ��� by the sadistic Rooi Rus Swanepoel ��� then flung from a window on the seventh floor of Gray���s Building, Johannesburg headquarters of the security police���.

Towards the end of his Memoirs, Karthada talks of how, on his first post-liberation visit to the rural town of Schweizer-Reneke (where he grew up), he ���paused at the vacant lots where our shop and houses had been razed to the ground in 1981 . . . . I was in prison when my mother, my brother Ismail and his wife Amina passed away���.

The prison was finally closed in 1996, turned into a museum, and declared a World Heritage Site in 1999. Visitors today have the good fortune to be taken round by a former inmate. It���s a sobering experience. Ahmed Kathrada, who is now eighty-six, remains chair of the Robben Island Museum Council.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers