Andrew O���Hagan on war and writing

Andrew O'Hagan, 2011; copyright: Robert Perry/TSPL/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

���I believe in the truth of what Martha Gellhorn said���, Andrew O���Hagan told Sam Leith at a ���Hidden Prologues��� event at Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel in Bloomsbury last week. ���If you���re going to write about war, you have to taste it.��� So, in 2013, for his fifth novel The Illuminations, O���Hagan spent a number of weeks with soldiers in Afghanistan. He was not, ���even for a day���, in the kind of danger faced by many war reporters, he said, but he ���did get to taste the fear because it was straightforwardly very frightening���.

With experience as a writer, he said, ���you come to know what you���ll need for the paragraph . . . . The journalist in me absolutely races into the middle of a situation like that to get the material���. He was particularly interested in how the soldiers spoke, and in ���the rhythm of their moral lives���; he found himself troubled, when he was among them, by the impression that video games had strongly influenced their attitude to conflict. His research also took him to war graves in France, where he reflected on our ���national myth of the beauty of sacrifice���. He described the poet Charles Sorley as a talismanic voice in the writing of the book, and recited (from memory) ���When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead���, which was found in Sorley���s knapsack after his death at the Battle of Loos in 1915:

. . . .

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead . . . .

O���Hagan is interested in fiction that explores the relationship between soldiers��� lives on the battlefield and their lives at home; so, in The Illuminations (see Kate Webb���s review of the novel here), readers are introduced not only to Luke, a captain in the Royal Western Fusiliers who is leading the delivery of equipment to an electricity plant at Kajaki, but also to his grandmother, Anne, once a talented photographer, who is struggling with Alzheimer���s. Anne���s part of the story, O���Hagan told us, was inspired by the life of a Canadian photographer, Margaret Watkins (1884���1969), who, after studying at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in Maine, entered a career in commercial photography, and in the 1920s achieved international recognition for a body of work that included portraits, street scenes and domestic still lifes.

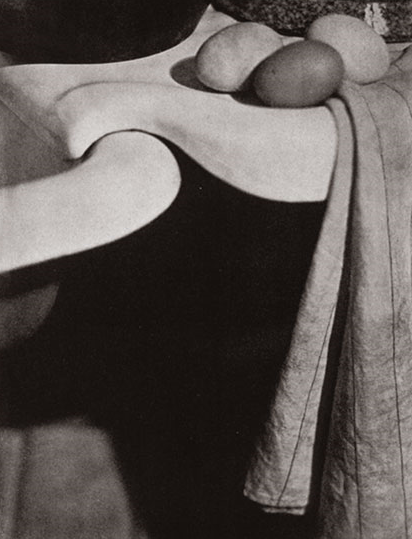

Watkins���s career was cut short when she moved to Glasgow to look after four elderly aunts. There, we were told, she became agoraphobic and stopped leaving the house ��� it is in large part thanks to a man called Joseph Mulholland, who lived near by, that she is known to us now: he noticed lights going on and off, and decided to knock on the door. Watkins later instructed him to open a particular packing case after her death; when, eventually, he did so, he found inside a huge number of negatives, contact sheets and prints dating from the period 1909���24. O���Hagan described Watkins���s photographs as ���miracles���, ���works of art���: ���she just had this absolute feeling for shape and for light��� (see ���Domestic Symphony���, 1919, and ���The Kitchen Sink���, 1919, below). Coming across her work, for him, ���was one of those moments that as a writer you get three or four times, if you���re lucky. I suddenly understood that there was a book to be written that hadn���t been written before, that was about the relationship between this woman and her vision of life ��� and her sense of the loss of her creative power���.

The weightiness of much of the conversation notwithstanding, this was a relaxed sort of evening (wine, canap��s, plush seating), and one rich in enjoyable digressions ��� on modern reading habits, for example (���I think people looked to novels once upon a time as a way to give ballast to their moral selves, and I don���t think people do that now���) and the decline of some varieties of long-form journalism (���I wrote a 12,000-word piece once about a bunch of lilies���). O���Hagan touched on writers��� certainties about what makes good and bad writing (���I'm always arguing with my friend Colm T��ib��n about this ��� everything Colm says about writing is really a justification for what he does���); and having, as a writer, strengths and weaknesses (���I was the Telegraph���s film critic for a while . . . . I don���t think I was very good at it, though . . . . Peter Bradshaw ��� he really cares whether a film���s good or not. I don���t���).

There was also an exchange with Lynn Barber, who was sitting in the audience, about approaches to interviewing: O���Hagan has had, since childhood, ���a completely insane ability to disappear���; he said of the five months he spent with Julian Assange (when working as his ghostwriter): ���He would ask for my opinion every five minutes and I���d say nothing . . . . I became like the Aga in the kitchen���. And we���ll be hard pressed to forget his descriptions of his grandmothers: one of them was ���a good-time girl. She loved dancing and singing���, while the other was ���absolutely bitter and went to Mass every day. She hated the idea that Protestants existed, and that was her main preoccupation���.

In talking about attitudes to writing, O���Hagan said: ���I don���t really believe at all in a hierarchy of forms���; ���writing well ��� it���s a bit like wanting to look all right . . . . It becomes instinctive���; and he said, of dialogue in fiction, ���If you���re serious about it, everything everybody says is filled with a kind of hinterland, and a DNA���. Meticulousness, it became clear, characterizes all his work as a writer ��� he was as thorough in his research for Anne���s part of The Illuminations as he was in that for Luke���s, spending hour upon hour with people suffering from dementia. It is not just war but all life, it seems, that needs to be tasted.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers