Iris Murdoch: letter-writer and eucatastrophist

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Dearest girl a RING! Thank you so very much. And what a lovely one ��� obviously magic ��� a ring of power. I think it is made of mithril. (I hope you know your Tolkien.)" The author of these words, Iris Murdoch, sent them to her dear friend Philippa Foot on December 23, 1969 ��� within a few years, as far as I can tell, of Murdoch starting to write her letters at the desk of the author she perhaps somewhat surprisingly alludes to here. . . .

Tolkien was surprised, at least. As noted in the TLS back in October, the Oxford philologist-novelist had, in 1965, received a "warm fan-letter" from the the Oxford philosopher-novelist. A recently published essay (by Scott H. Moore, in Tolkien among the Moderns) suggests that the affinities between the two of them run deep: troubled by what she saw as the potentially dubious consolations of fantasy writing, her own novels nonetheless reflect Tolkien's concept of the "eucatastrophe" ��� not a sudden, sweeping disaster but a sudden, sweeping miracle that puts everything right. A. N. Wilson, who knew Murdoch and was taught by Tolkien's brother Christopher, has observed that neither author could be considered an especially talented stylists (that most deadly of literary virtues). Both preferred ���simply charging on��� as they told their tales; their conversations, to Wilson's horror, could turn on ���abstruse points of elvish lore���.

So to those prepared to put their novels side by side, perhaps the connection is not so surprising after all ��� maybe think of them as novelists who are equally concerned with the struggle between good and evil yet take different routes to encompass that struggle.

Not that Murdoch was uncritical of Tolkien. In January 1969, twelve months before demonstrating to Foot her knowledge of metals peculiar to Middle-earth, she had asked one of her students at the Royal College of Art: "Have you read Lord of the Rings yet I wonder? I have just been reading The Hobbit which has some very good scenes in it. (Tolkien muffs all the big scenes in L of R I'm afraid ��� it should be much more drawn out)".

It's a long time since I read Tolkien, so I can't say if she's right about that failing (can you?). But this observation does put me in mind of those drawn-out scenes in Murdoch's own fiction. She excelled in devising such atmospheric sequences: Jake's pursuit through the streets in Under the Net; the two boys clinging to the ominous tower (it "emerged blackly against a black sky") in The Sandcastle; Ducane, Pierce and Pierce's dog Mingo (some thoroughly Murdochian nomenclature there) trapped in a littoral cave by the rising tide in The Nice and the Good (that cave has a chimney; imagining escaping that way, Ducane realizes the water "would rush up that narrow sloping hole like a demon . . .").

One more Tolkien���Murdoch connection: both were prophetically praised in the TLS on the publication of their first works of fiction, Under the Net appearing to its anonymous reviewer to show that "the gifts which have gone to its making promise great things", and The Hobbit, two decades earlier, being hailed as a likely "classic" for the future. The critical prophet, admittedly, being Tolkien's friend C. S. Lewis.

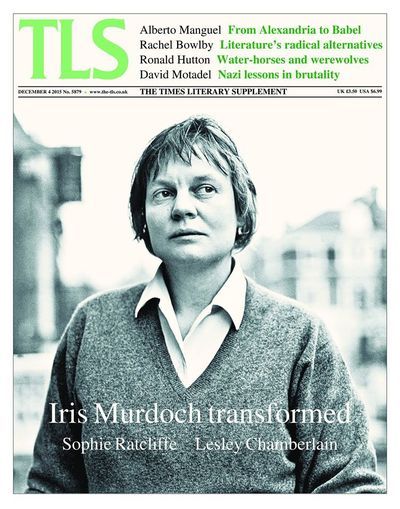

Both of the letters quoted above appear in Living on Paper, the generous selection of Iris Murdoch's letters recently published by Chatto and Windus; a photograph of the celebrated roll-top desk is reproduced here, too, in its place in the study "where Murdoch would sometimes spend up to four hours a day writing letters", after doing a day's work at the desk in her other study. While noting those passing references to Tolkien, I've been reading the volume's many letters to Brigid Brophy with a certain interest. Sophie Ratcliffe's review leads this week's TLS, which some may enjoy reading, its superior critical qualities aside, in the wake of a complaint from Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, the editors of Living on Paper, about how other reviewers have portrayed the author ��� as ruthless, "morally bogus" and so on. Amid the usual mixture of howling-mad and sensible comments in response to them is a reply in the latter category from one of those reviewers, John Sutherland. A review of a review of some reviews, you might say; this one could run and run. (Let's hope it doesn't.)

By quiet contrast, the most recent edition of the Iris Murdoch Review, produced by Horner and Rowe, among others, pays tribute to Murdoch's husband John Bayley, and includes his correspondence with Michael Howard. Bayley introduces her in 1955 as "Earning about 2 x as much as I do & wedded to literary ambitions": "We are much in love, & live in great harmony & domesticity". So how about a quotation, from 2004, for the paperback edition of Living on Paper?

"Funny thing letters. Iris was one of the worst of correspondents, perhaps because she always conscientiously answered every one she got, and there were a great many, often fairly dotty. When I was courting her, and wrote her what you might call long and pseudo-brilliant letters, I always got a few ��� a very few ��� hasty but kindly words in reply. Letters were emphatically not her mode of expression or being . . . ."

OK, perhaps not. . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers