Eliza Soane commemorated

By MICHAEL CAINES

As mentioned by Mika Ross-Southall on this blog last month, the new exhibition at the Soane Museum surveys a morbid scene: if there is one architect who could inspire an exhibition entitled Death and Memory, it's Sir John Soane. Not content with imagining his Bank of England as a ruin, and commissioning Joseph Michael Gandy to depict such scenes for him, he turned his own house into a delirious reliquary, abounding in statuary and other fragments of antiquity, including several cinerary urns and an alabaster pharoanic sarcophaghus, through which to educate and overawe posterity.

But not Soane's own posterity ��� not the sons he had hoped would continue his work. Indeed, when his younger son George published two anonymous attacks on his father's architectural achievements, in 1815, Soane regarded them as his wife Eliza's "Death Blows"; she died a few weeks later, on November 22 that year. There was to be no Soane lineage of architects, at least not directly; instead, there is his museum. And there is also the remarkable mausoleum where some thirty people gathered on Monday to pay tribute to Eliza. . . .

The 200th anniversary of Mrs Soane's death was a Sunday, and deemed to be impractical, so a brief ceremony was held the following day, on November 23, at the Soane mausoleum in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church. It was here in the mid-1860s, about fifty years after her death, that the young Thomas Hardy oversaw a mass excavation of bodies, as thousands of graves made way for the Great Midland railway out of the new St Pancras railway station (where George Gilbert Scott built the Midland Grand Hotel; it was his grandson Giles who took inspiration from the Soane mausoleum for the British red telephone box).

Hardy captured something of the atmosphere of the place in his poem "The Levelled Churchyard", written at a later date, and partly with reference to similar works in Dorset:

O passenger, pray list and catch

Our sighs and piteous groans,

Half stifled in this jumbled patch

Of wrenched memorial stones!

We late-lamented, resting here,

Are mixed to human jam,

And each to each exclaims in fear,

"I know not which I am!"

(Note the characteristically strange yet striking use of the word "jam" . . . There is also, to take this digression even further, a more recent and superbly ghastly take inspired by these experiences, The Hardy Tree by Iphgenia Baal.)

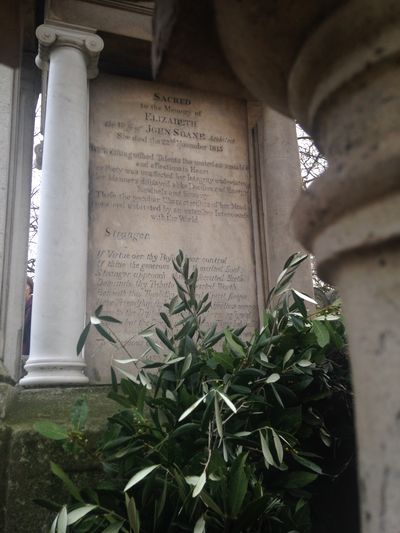

No such rotten luck for Eliza Soane and the remaining son, John, and the husband who were later to be interred with her. Set within the bounds of a circle of iron railings, the Soane mausoleum still stands within listing-and-catching distance of the chuntering trains going in and out of St Pancras. Its isolation is nothing like the romantic scene pictured by George Basevi in 1816 ��� but it is also nothing like the "jumbled patch" Hardy saw assigned to the residents of the neighbouring graves, and certainly not "crowded", as a fellow journalist recently put it. On the contrary, it is appropriately set apart, a monument without a trace of Christian imagery in its design (Soane, a Deist, disliked organized religion) making its bold architectural statement in the grounds of an Anglican church. To me, it has always seemed surprisingly modest in scale, compared to Basevi's depiction. Intimate or domestic even ��� as might be thought fitting for a family tomb.

After the necessary warm drinks in the church itself, we ambled across the churchyard, and the gate into that iron circle was opened for us. The museum's Acting Director, Helen Dorey, gave a speech, noting Eliza's own collecting activities and how vital she was to her husband. (Dorey is also giving a talk about "the Soane as a shrine" tomorrow night.) It seems to have been a happy marriage, of three decades' duration; although readers of Gillian Darley's John Soane: An accidental romantic will know that there were rougher times as well as smoother ones, there is no doubt he was devastated by her death. A "delightful, perceptive" person, Eliza had "acute intelligence" and a "shrewd head for business". The Soane library of some 6,000 books is not exclusively his collection, but includes some titles with her name inscribed in them: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Letters; Samuel Johnson's Dictionary; a second-hand copy of Elizabeth Griffith's Essays Addressed to Young Married Women. Eliza Soane also, Darley suggests, "brought Soane the personable architect into being", playing the "socially adept" hostess and the "confidante". He needed such guidance. Could it be said that he was, in some sense, her great achievement?

Soane's grief found expression in the mausoleum he designed for her, erected in 1816; he could not then bear to go and see it for himself. The wreath laid there on Monday was a reminder that anybody who admires his work is in Eliza Soane's debt, too.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers