We Will Rock You

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

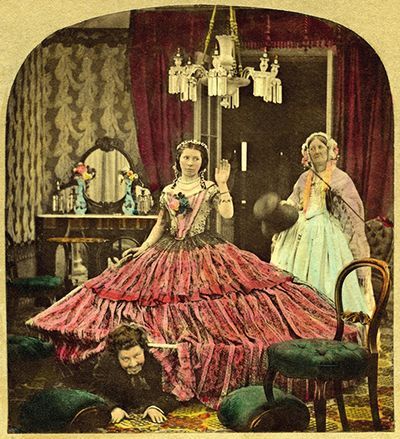

On Thursday night I watched Brian May emerge from underneath a woman���s skirt. Being on stage, commanding an audience ��� it���s nothing new for Queen���s lead guitarist. What is new is his focus on Victorian crinolines or, to be more precise, stereoscopic photographs of them.

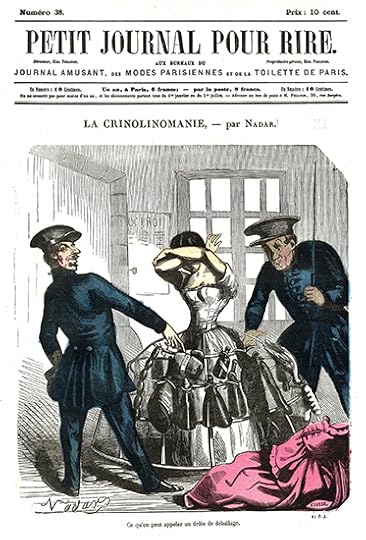

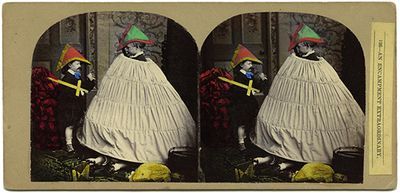

The craze for these undergarments in the mid-nineteenth century coincided with the invention of the stereoscope, May told us last week at the launch of his new book, Crinoline: Fashion���s most magnificent disaster, co-written with Denis Pellerin (they call it a ���disaster��� because the undergarment was a significant fire hazard: there were around 300 deaths a year from fire accidents during the crinoline���s peak). Stereoscopic cards, dubbed by the press as the ���Poor man���s picture gallery���, presented scenes, such as the Egyptian pyramids and crocodiles, in life-like 3-D to a public that had never seen or experienced anything quite like it before.

According to the London Stereoscopic Company (May is responsible for reactivating it), stereoscopic images can be created using a normal camera: first, capture the subject while you are standing on one leg, then transfer your weight to the other leg and capture the subject again. This gives you two views of the subject, taken from positions roughly the same distance apart as the eyes are; once these images are mounted side by side and seen through a stereoscopic viewer, they���ll give a 3-D rendering of the subject. (A greater distance between the first capture and the second will achieve an exaggerated stereo effect.)

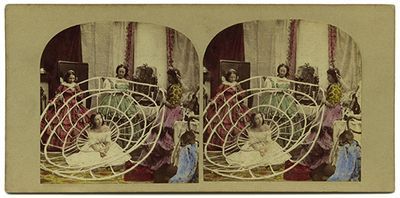

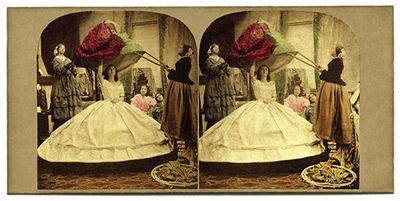

At Christmas in 1857, ���Mysteries of the Crinoline��� (examples above) was one of the most popular series of stereoscopic pictures sold. Crinolines clearly caught people���s imaginations, especially when viewed in stereo ��� a format that is all about volume, depth, space; just like the crinolines themselves. In its first incarnation during the 1830s, the crinoline was a petticoat stiffened with horsehair (from the French crin) worn under a skirt. It became heavier and more voluminous through layering, which prompted a short-lived inflatable air-hoop version (prone to punctures and emitting rude noises) in the late 1840s, until the recognizable crinoline cage ��� the ���independent carcass��� ��� came into being, with hoops made from whalebone, cane or steel.

One interesting chapter in Crinoline concentrates on their manufacture. The growing demand for steel petticoats triggered a boom in England���s steel industry, and cartoons show blacksmiths at work (the curious captions include ���Locksmith to the Ladies��� and ���Ladies Tailor���). ���While the people down South were complaining about this ridiculous fashion���, the authors write, ���Sheffield and Birmingham manufacturers were rubbing their hands with glee, and secretly wishing it a long prosperous reign.���

Crinoline smuggling across borders was a common pursuit. A few of the items found hidden beneath women���s petticoats by the police are listed here, including obscene pictures; a turkey; twelve partridges; a hare and three rabbits; 32 lbs of tobacco; 22�� lbs of cigars; counterfeit money; four bottles of brandy and eight flasks of Eau de Cologne; 30 lbs of gunpowder; weapons (during the American Civil War); banned books and magazines (Henri Rochefort���s La Lanterne).

The most famous crinoline wearer was probably the Empress Eug��nie de Montijo, the wife of the French Emperor, Napol��on III; and May and Pellerin���s book contains some very funny contemporary reactions to her. Here���s one from Lloyd���s Weekly Newspaper on Empress Eug��nie���s visit to England in September 1856:

���A little reflection will convince even the English doubter that the influence of the Empress of the French upon English feelings and English customs, is far greater than that of any possible policy on the part of her astute and saturnine lord, the Emperor. If the policy of the Emperor has led to the alliance of Englishmen and Frenchmen, the example of the Empress has undoubtedly produced the isolation of Englishmen from Englishwomen. We, of course, allude to the crinoline, or horse-hair petticoat, first endued [sic] as a delicate device by Eug��nie, and immediately adopted by hundreds of thousands of most thinking spinsters, wives, and widows, of England . . . . Eug��nie has reduced the British bonnet to the dimensions of a scallop-shell, and expanded the British petticoat to the size of a cricketer���s tent.���

And what was Napol��on���s opinion of his wife���s fashion choice? Apparently he expressed it to the Stamford Mercury three years later:

���In the midst of all the serious combinations in which the Emperor is plunged, it is still delightful to observe that time remains for summer trifling. Thus, we learn that the Emperor, with that tenacity and perseverance for which he is distinguished, nothing daunted by the signal defeat he has sustained, both at Paris and St. Cloud, in the war he so imprudently waged against crinoline, has renewed the combat at Biarritz, and has maliciously taken to driving a low, narrow Victoria, with two ponies, instead of the high britchka he has been always accustomed to sport at the seaside. This new taste, although pouted at by the Empress, on its first adoption, has since become tolerated; and, certainly, the crinoline has diminished considerably, as it is observed no longer to hang over the side, and to draggle on the steps, as it did at first. The Emperor laughs slyly at the silent change which is gradually taking place, and has already expressed a hope that, before the Court returns to Paris, the eye of the Empress will have become accustomed to the diminished size of her skirts, that her Majesty will no longer be able to tolerate those of still disproportioned, though already diminished volume, which she will find the fashion yet on her arrival.���

Like Marie Antoinette almost a hundred years before her, Empress Eug��nie claimed that these lavish and innovative dresses were her ���political outfits��� ��� a way of promoting and supporting France���s economy. We all know how it ended for the former. But the latter died aged ninety-four, having been a forthright campaigner for gender equality (she pressured the Ministry of National Education to give baccalaur��at diplomas to women, and tried ��� unsuccessfully ��� to persuade the Acad��mie fran��aise to elect George Sand as its first female member). It seems her husband���s duress didn���t quite pay off.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers