A nosy Parker

"Shared Fate (Oliver)", 1998 �� Cornelia Parker. Photograph by Dan Weill

"Shared Fate (Oliver)", 1998 �� Cornelia Parker. Photograph by Dan Weill

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

���I like objects or pictures with a caption���, the British artist Cornelia Parker told us a few weeks ago at the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury, ���or I like to switch captions around.��� It���s no surprise, then, that she has curated a playful, object-and-story-based exhibition there, having enticed her Royal Academician friends, as well as famous writers and musicians, to respond to her theme of ���found���.

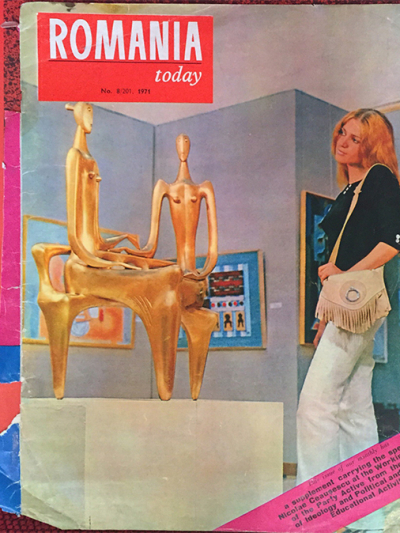

Displayed among the galleries��� permanent collection, these ���found��� works cleverly interact with what���s already there: hung between several oil paintings of austere wigged men, for example, we see the word ���FEELINGS��� made out of white neon strip-lighting by Martin Creed; Dorothy Cross���s wormy calcified bottle, discovered when she was deep-sea diving, is positioned under a traditional nautical painting; several copies of Romania Today (an English-language magazine promoting Nicolae Ceau��escu���s Communist regime) from Jarvis Cocker are accompanied by his description of how, one day in Bristol in 1985, he came across a bin bag full of the magazines ��� the garish, ���pumped up��� colours would later influence the look of his band Pulp; and all alone, in the corner of an ornate room, sits Gavin Turk���s ���Nomad��� (2002), a bronze cast of a sleeping bag that���s been meticulously painted to resemble the synthetic material of the original, with a timely blurb about homelessness, the refugee crisis, and the Foundling���s own history as a charity caring for abandoned children.

Part of Parker���s inspiration for the exhibition came from this history: set up in 1739 by Thomas Coram, the Foundling Hospital was supported by William Hogarth (who encouraged leading artists to donate work to the hospital, thereby establishing it as Britain���s first public art gallery) and George Frideric Handel (who gave an organ and conducted benefit concerts of the Messiah every year in its chapel). Parker was fascinated by the thousands of eighteenth-century tokens (small objects, such as engraved pennies, or swatches of embroidered fabric) left behind with the babies by the mothers as a means of identification should they ever return to claim their child.

Almost 300 years later, Parker is doing something similar in her work: ���I���m not trying to represent; I���m using the things themselves to stand in for other things���. Taking everyday objects laden with cultural meaning, she subjects them to a process (blowing up, flattening down etc) to make them unfamiliar and unfathomable, often adding an ingenious caption. (On the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, you���ll currently find her ���Transitional Objects (PsychoBarn)��� ��� the fa��ade of a red barn, taken from upstate New York, held up by scaffolding. It���s meant to tap into traditional New England architecture and paintings by Edward Hopper, and also bring the Bateses��� sinister family house from Hitchcock���s black-and-white Psycho into colour.)

Her own pieces are some of the best here. ���Shared Fate (Oliver)��� (1998) is a doll cut in half ���by the guillotine that chopped off Marie Antoinette���s head. A tweak of history causes a fictional character to share the same fate as a real queen���, the caption tells us. One member of the audience didn���t approve of the work���s re-display in a former children���s home. ���Maybe I was more crass back then���, Parker responded. She found the toy in a Brick Lane shop ���and I wanted to give it a reason for having such an anguished look like that on its face���. On a more serious note, Parker continued, it shows how objects have a language. ���A decapitated doll has more impact displayed in here than in a white gallery space.���

Three deflated balloons in a glass cabinet (also by Parker) were another highlight for me: one is black, and entitled ���Breath of a Librarian���; another, ���Breath of a politician���, has ���Jeffrey for Mayor��� written on it; and ���Breath of a Scotsman��� is blue with a white cross. Alongside these sits the writer Deborah Levy���s blue bead with a broken wire thread: after her mother died, Levy collected lost beads and buttons from the streets. Coming across these curious pieces as you walk around the rather sedate Foundling Museum feels intimate, even intrusive.

Still from "FILM" by Michael Craig-Martin, 1962-3

Still from "FILM" by Michael Craig-Martin, 1962-3

On the top floor, there���s the only film Michael Craig-Martin has ever made. Found by his daughter in 2000 at the bottom of a trunk, the black-and-white 16mm film was created in Connemara on the west coast of Ireland in 1962, for his undergraduate degree. It features swirling waves, mariners sorting kelp, close-up abstracted shots of rural churches, relic-like buildings and a white-plaster Jesus on a wooden cross. Children, lined up on stone walls and staring directly at the camera, strike an inadvertent chord here, just like Parker���s decapitated doll. ���Really it���s a collection of high-profile discards, repositioned and looked at with a new eye���, she concluded. ���And I���m a nosy parker.���

"Found" runs until September 4.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers