Sir John Soane���s danse macabre

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Sir John Soane ��� like his house (now a museum in Lincoln���s Inn Fields), his architecture and his writing ��� is peculiar and perplexing. Without him the Dulwich Picture Gallery wouldn���t look like it does, nor phoneboxes: the family tomb Soane designed and built for his wife Eliza, after her death in 1815, in St Pancras Old Churchyard (one of only two Grade I listed monuments still standing in London; the other is Karl Marx���s tomb in Highgate Cemetery) apparently inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott���s design of the British red telephone box.

A fanciful, colour-washed painting (above) of this monument (alongside original drawings created by Soane���s architectural office) is on display in a new exhibition, Death and Memory: Soane and the architecture of legacy, at the Soane Museum. Obsessed with funerary architecture, Soane didn���t simply make the tomb a memorial to his wife; it also commemorates his favourite architectural motifs. Here we have a square-based shallow dome, incised pilasters, an abundance of ancient death symbolism.

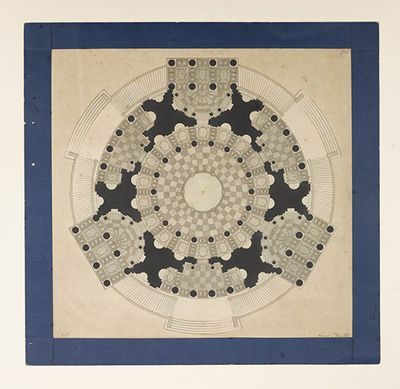

Other architectural drawings, selected by the curators from the 30,000 in the museum���s archive, show circular mausoleums, obelisks honouring Battles at Trafalgar, Waterloo and Blenheim, and a plan of an unexecuted monument to George Washington ��� this hangs below a beautiful, minimalist interpretation of the plan from the 1970s���80s (circles within squares, and a delicate row of twig-trees in the corner, like a Sol LeWitt illustration), neatly suggesting that Soane���s funereal influence continues. And, thankfully, disproving that architectural drawings and models are dull or nonsensical to an amateur. (If you���ve been to the Royal Academy���s Summer Exhibition over the past few years, you may have noticed a change in the architecture room: almost-impenetrable computer graphics are now overshadowed by dynamic designs that are painted, photographed or inked; there���s even an award for the best model, partly based on architecture, partly on the execution of the model itself.)

Plan of a mausoleum by William Chambers from the Soane collection

Plan of a mausoleum by William Chambers from the Soane collection

For me, one item in Death and Legacy is particularly fascinating: a cork model of an Etruscan tomb collected by Soane ��� the roof gapes open to reveal a comical skeleton lying on a plinth, huge ceramic vases, and stucco pigs and dogs on the walls, all of which are slightly off-scale and archaeologically inaccurate. This is much like the inside of the Soane museum itself, with its sombre catacomb-like basement, relics, altarpieces and Egyptian-mummy cases placed in every crevice.

Henry James picked up on this motley, unique collection in his short story ���A London Life��� (1888):

���The heterogeneous objects collected by the late Sir John Soane are arranged in a fine old dwelling-house, and the place gives one the impression of a sort of Saturday afternoon of one���s youth ��� a long rummaging visit, under indulgent care, to some eccentric and rather alarming old travelled person.���

Preliminary design for the Soane Museum, by James Adams, 1808

Preliminary design for the Soane Museum, by James Adams, 1808

Soane was so preoccupied with ruins, remains and shaping memory through architecture that, as well as making his house an ���academy��� of design and a personal legacy, he left behind sealed receptacles (a sort of time capsule) a few months before his death with instructions for them to be opened on the fiftieth, seventieth and eightieth anniversaries of his wife���s death ��� as though their contents had some cosmic significance. Instead, we find a pair of his masonic gloves; false teeth; a small, round piece of glass from Sudeley Castle; correspondence relating to his wayward son George (who refused to become an architect, constantly badgered his parents for money ��� he was a novelist ��� and wrote critical reviews of his father���s buildings, which Soane ��� disappointed, saddened ��� framed and displayed in the house, labelling them as his wife's ���Death Blows���); and a bizarre manuscript, Crude Hints Towards an History of My House in Lincoln���s Inn Fields, now republished by the museum to accompany the current exhibition. In the guise of an antiquary, Soane here imagines his house as a ruin in the future being inspected by visitors who speculate about its origins and function. Was it a Roman temple, a burial site, a monastery, a magician���s lair? The manuscript is written in a single column down the right-hand side of the page, leaving plenty of space for marginal notes ��� of which there are many, mostly challenging the haughty voice in the main text (���is it possible Architecture might have been better understood . . . in Italy than in Britain ��� in the succeeding times the Britons were designated ���barbaros Brittannos������). On seeing a fragmentary inscription ���et filii filiorum���:

���What an admirable lesson is this work to shew the vanity of all human expectations ��� the man who founded this place piously imagined that from the fruits of his honest industry & the rewards of his persistence [and] application he had laid the foundation of a family of Artists and that the filii filiorum of his loins might, smitten with the love of Art and anxious to shew their gratitude for the benefits & care & comfort they derived from it, dwell in this place from generation to generation ��� Alas poor man he flattered himself that a race of Artists would have been raised up whose efforts from the advantages they set out in life with . . . would have raised Architecture to its meridian splendour ��� Oh man, man, how short is thy foresight.���

Although, there are, of course, three alternative endings. The third one is the most whimsical, dark and, incidentally, my favourite, its final line being: ���Oh what a falling off do these ruins present ��� the subject becomes too gloomy to be pursued ��� the pen drops from my almost palsied hand . . . ���. Fingers fall away from keyboard doesn���t quite have the same effect.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers