David Pilling's Blog, page 7

March 3, 2022

King of the Welsh

In 1141 King Madog of Powys and his brother-in-law, Cadwaladr ap Gruffudd of Gwynedd, joined forces with Earl Ranulf of Chester to fight King Stephen at the battle of Lincoln. Stephen was defeated and captured, and some argue that up to two-thirds of the 'rebel' army was composed of Welshmen. Thus, for those who get excited about this sort of thing, a largely Welsh army overthrew (albeit temporarily) a king of England.

In 1141 King Madog of Powys and his brother-in-law, Cadwaladr ap Gruffudd of Gwynedd, joined forces with Earl Ranulf of Chester to fight King Stephen at the battle of Lincoln. Stephen was defeated and captured, and some argue that up to two-thirds of the 'rebel' army was composed of Welshmen. Thus, for those who get excited about this sort of thing, a largely Welsh army overthrew (albeit temporarily) a king of England.King Madog cultivated strong political alliances with Earl Ranulf and Henry II, after the latter's succession to the English throne in 1154. He did so for practical reasons (as if there was any other kind). Powys was constantly threatening to collapse into civil war, and Madog needed all the external support he could get to keep his realm in order. He also needed money and soldiers to resist the ambitions of the rulers of Gwynedd.

There was another motive. When Ranulf died in 1153, he left a six-year old heir, Hugh. Until the boy came of age the earldom of Chester was taken into royal custody. From Madog's perspective, this meant that his eastern border now lay adjacent to lands controlled by royal officers. So it made sense to have peace with the new king. It helped that Henry was well-disposed towards Madog anyway, since the latter had supported the Angevin cause in 1141.

Cadwaladr also had a pressing need for allies. He was alienated from his brother, Owain Gwynedd, and had taken refuge at Earl Ranulf's court when Owain drove him from Anglesey in 1151 or 1152. Interestingly, he appears as 'King of the Welsh' on two of the earl's surviving charters, sealed at Chester. Owain had assumed the title Prince of Wales – or Prince of the Waleses, to quote the awkward literal translation from the Latin – but his brother was calling himself a king. Not just any king, but ruler of the whole of Wales.

Madog's alliance with Henry II seems to have caused unease, given that the English were supposed to be the traditional enemy. This tension is reflected in an elegy composed by Cynddelw, in honour of a fellow poet killed at the battle of Hawarden Wood in 1157.

Cynddelow deploys the phrase 'A! Glyw Deifr a'i gwelsent' (Ah! The Deiran warriors who beheld him'). The word Deiran/Deirans was used to describe the English, and Cynddelw implies the enemy were admiring his subject's bravery in battle. What he does not acknowledge is that the man died fighting in the vanguard of King Madog, against the forces of Owain Gwynedd and on behalf of the king of England.

Published on March 03, 2022 05:48

February 28, 2022

Cash on the barrel

In 1171 Rhys ap Gruffudd, lord of Deheubarth, attacked Owain Cyfeiliog of Powys. The trigger for this was probably Owain's foundation of Strata Marcella, which established him as a founder and patron of a Cistercian house. This in turn made him a rival to the southern prince, who would not tolerate opposition.

In 1171 Rhys ap Gruffudd, lord of Deheubarth, attacked Owain Cyfeiliog of Powys. The trigger for this was probably Owain's foundation of Strata Marcella, which established him as a founder and patron of a Cistercian house. This in turn made him a rival to the southern prince, who would not tolerate opposition. The subsequent battle was fought inside Cyfeiliog. One of the casualties was Iorwerth Goch, half-brother to King Madog, last ruler of a united Powys. Iorwerth was made the subject of a 'marwnad' by the poet Cynddelw, and further evidence of his death is found in English records: his Exchequer subsidy was stopped after 47 weeks of the financial year 1170-71.

Owain Cyfeiliog appears to have come off worst. The war came to a sudden end, and he was obliged to hand over seven hostages to Rhys. However, Rhys then withdrew to his own lands without further reprisal, suggesting he had only won a nominal victory.

The real loser, Iorwerth Goch, was a significant player in Wales. He had previously supported his brother, King Madog, when the latter allied with Henry II against Owain Gwynedd. In the 1160s he was one of several Welsh castellans in receipt of English payments to guard the borders of Pows against invasion from Gwynedd.

However, in 1165 Iorwerth was one of the great swathe of Welsh rulers who suddenly defected to Owain Gwynedd against the king. When Henry tried to move against then, his expedition crashed to a halt in the Berwyn mountains as a result of bad weather, terrible logistics and ferocious Welsh counter-attacks.

Iorwerth subsequently went back to the king, and in the following years his payments resumed. His motives for switching back and forth are unclear, especially as Owain had murdered his brother and nephew in 1160. Possibly it was a case of: cash on the barrel, son.

The following year, 1166, Iorwerth was driven from his lands in Powys by Owain Fychan and Owain Cyfeiliog. This seems odd, since Iorwerth and Owain Cyfeiliog were usually allies. Owain may have taken advantage of Iorwerth's absence in England, where he was engaged in selling horses for the king's use.

In 1167 the tables turned yet again, when Owain Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffudd teamed up to attack Owain Cyfeiliog; this was a recreation of the previous alliance of 1165, but aimed against a fellow Welsh prince rather than the king.

Iorwerth's movements are obscure until the conflict of 1171, in which he met his Waterloo. He had evidently patched up his conflict with Owain Cyfeiliog, and died fighting an incursion from the south.

Afterwards Rhys was summoned to an interview with King Henry in the Forest of Dean. It resulted in no punishment, possibly because Henry was left totally bewildered.

Published on February 28, 2022 07:00

February 26, 2022

Cinco Villas

A castle inside Cinco Villas, a region or comarca (county) that used to lie inside the kingdom of Aragon in north-east Spain.

A castle inside Cinco Villas, a region or comarca (county) that used to lie inside the kingdom of Aragon in north-east Spain.

Very nice, you might say, but what has it got to do with British medieval history? For me. this subject is always more interesting when you take a wider view; that is certainly how contemporary rulers looked at their world.

In December 1282 Edward I requested his vassal Gaston Moncada, viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony, to lead a hundred Gascon knights and men-at-arms over the Pyrenees. Their mission was to aid Alfonso X, King of Castile and Edward's brother-in-law, to crush a revolt led by Alfonso's son, Don Sancho.

Gaston agreed. On 6 June 1283 he was at Bordeaux, where he agreed to refund 1000 marks to the king, advanced to him to finance the military expedition. In the next few months he submitted claims for expenses in serving with the king of Castile.

On 16 January 1284 Gaston was at Pamplona, chief city of the kingdom of Navarre. It appears he had joined the French feudal host, sent by Philip III – Philip 'the Bold' – to seize control of the city and fight King Peter of Aragon, who had sided with Don Sancho against Alfonso.

The chronicle of Bernard Desclot records that in 1283 Philip sent a fresh army over the Pyrenees to reinforce his garrison at Pamplona. They attacked the castle of Ull, south-east of the city, held by an Aragonese garrison of just thirty men. The French stormed the outer works and the barbican, and drove the defenders back into the donjon. They then dug a mine, which caused half of the donjon to collapse. Thanks to the piles of rubble, the French had to use ladders to escalade and seize the castle. Given his presence at Pamplona shortly afterwards, Gaston and his men were probably involved in the attack.

Ull was part of a chain of towers and castles inside the 'comarca' of Cinco Villas. It appears to have vanished, but many of the larger fortifications can still be seen.

This tale also shows the importance of the Gascons as a military resource to the Plantagenet kings of England. At the same time as Gaston was fighting in Navarre, Edward had dispatched a larger force of 2400 Gascon knights and crossbowmen to crush the revolt of Prince Dafydd in North Wales.

(Thanks to José Luis Pinto Fernades for helping me with the geography)

Published on February 26, 2022 07:01

February 24, 2022

Knowest thou, lord

In 1282 the Count of Armagnac, Géraud VI, was seized and imprisoned by the seneschal of Toulouse. At this stage Armagnac, situated between the Adour and Garonne rivers in the lower foothills of the Pyrenees, was part of the Plantagenet duchy of Gascony. Géraud and his brother, the Archbishop of Auch, hated the French and were constantly arguing with the seneschal at Toulouse, Eustace de Beaumarchais.

In 1282 the Count of Armagnac, Géraud VI, was seized and imprisoned by the seneschal of Toulouse. At this stage Armagnac, situated between the Adour and Garonne rivers in the lower foothills of the Pyrenees, was part of the Plantagenet duchy of Gascony. Géraud and his brother, the Archbishop of Auch, hated the French and were constantly arguing with the seneschal at Toulouse, Eustace de Beaumarchais.That, at least, was the common understanding. One man who did not buy it was Jean de Grailly, Edward I's seneschal of Gascony. The 'Lettres de Rois', a printed compilation of medieval correspondence between the courts of England and France, contain a long series of spy reports from Grailly to his master. These include several letters in which the seneschal gives his version of events in Armagnac.

In the first letter, Grailly describes a report from one of his agents in Gascony. This man had discovered that Géraud and his brother had come to a private deal with the king of France, Philip III. The archbishop had agreed to submit his temporality – secular lands and goods – to the court of France. Philip would then use that as an excuse to seize possession of all the churches in the province of Auch.

The archbishop would then claim the lands of Armagnac and Fézensac from Edward. If his request was granted, those lands would then be handed over to Philip. Thus, without raising a finger, the French king would have conquered a sizeable chunk of Gascony.

However, it appears the conspiracy was abandoned. On 19 May the seneschal dispatched a second letter to Edward:

“Knowest thou, Lord, that the Count d'Armagnac was locked up in the castle of Toulouse. It seems to me and many others that if the brothers are thus oppressed they will be compelled to submit themselves, through who knows what trumped-up context, to the King of France.”

The seneschal had changed his tune. Instead of a plot, he now claimed that Géraud and his brother were being oppressed by Philip. Edward then received two conflicting reports from Géraud and his rival Eustace. These two accused each other of stirring up war in Armagnac, and building illegal forts to use as bases to raid each other's lands.

The king's response was to do nothing very much. He privately agreed with Grailly's suspicions, but without firm evidence he could not simply arrest the Count of Armagnac. Besides, Géraud was already in a French prison. If it was all a ploy, then let him cool his heels for a while. On 18 November Edward replied to the count that he could not always help his vassals; however, he sent his condolences and advised Géraud to make use of Edward's lawyers in Paris. Also, if Géraud had any friends in Paris, perhaps it might be worth contacting them. I

The Armagnac crisis is another of the endless problems in Gascony. After the Treaty of Paris (1259), the kings of France were constantly seeking to interfere in the duchy's affairs, and weaken the authority of the Plantagenet king-dukes. One method was to undermine the loyalty of the local nobility. The Gascons in turn sought to profit by playing off their rival overlords against each other. All the Plantagenets could do was monitor events and maintain networks of spies and agents.

Published on February 24, 2022 03:20

February 23, 2022

Due fidelity

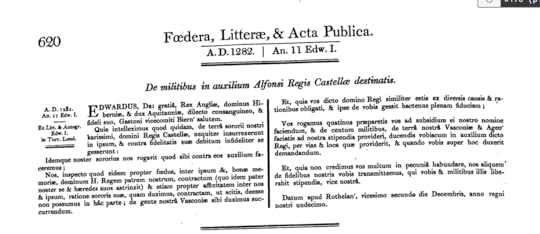

A letter dated 22 December 1282, from Edward I to Gaston Moncada, Viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony. The attached transcript is from a printed collection of diplomatic correspondence called the Foedera; the original is held in the National Archives at Kew.

A letter dated 22 December 1282, from Edward I to Gaston Moncada, Viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony. The attached transcript is from a printed collection of diplomatic correspondence called the Foedera; the original is held in the National Archives at Kew.This letter is used by Kathleen Neal as an example of Edward's delicate treatment of his Gascon subjects. Gaston had frequently rebelled against the king and his father, Henry III, but by 1282 was reconciled. Edward had been asked by his brother-in-law, Alfonso of Castile, to send troops to help him fight a civil war. Occupied with a rebellion in Wales, Edward could not go to Castile himself, or spare English soldiers. His solution was to ask Gaston to go in his name.

This military summons was not expressed as a demand. Instead it was framed as a polite request, in which Gaston was also asked his advice on the situation in Castile. This was not because Edward necessarily wanted his advice, but the aim was to soothe Gaston's touchy sense of pride and honour, and make him feel valued. As Neal puts it:

“Gascon loyalty could not simply be expected or demanded. It had to be argued for, by articulating it as an ideal and a proper course of action, and by specifying the personal consequences of failure”.

By personal consequences, Neal is not referring to punishment, but the potential damage to Gaston's image and reputation if he failed to oblige the king.

The letter opens with a moral evaluation of the war in Castile:

'A certain man, from the land of our dearest brother in law, the lord king of Castile, has risen up against him wickedly, and conducted himself faithlessly against his due fidelity'.

The emphasis on 'wickedness' and bad faith is entirely calculated. Edward follows by articulating his reasons for assisting Alfonso; these include the kinship between the two kings, due to Edward's marriage to Alfonso's half-sister, Eleanor of Castile; the peace between the two kingdoms; and Gaston's personal loyalty towards Alfonso. For good measure, Edward reminded Gaston that he had shown the king of Castile 'full fidelity up to now'; the implication being that he was duty-bound to continue doing so.

Thus, the rhetoric of summons was cast as part of a continuing tradition of loyal service, past and present. Edward was also careful to make use of the highly courteous verbal pairing 'requirimus et rogamus', the highest register of epistolary politeness. This cast the summons in the form of a voluntary act, based on a tradition of service and the promise of further recognition and reward. These cumulative obligations gave Edward the necessary leverage to gain Gaston's service, and send him to Castile at the head of '100 knights of Gascony and Agen'.

They weren't daft, these medieval types.

Published on February 23, 2022 05:33

February 22, 2022

Banner-chiefs

One of the notable features of the Anglo-French war of 1294-1303 is the loyalty of the Gascony nobility to the Plantagenet regime. This was in spite of very difficult circumstances: for nine years most of the duchy was occupied by the French, including the chief city of Bordeaux.

One of the notable features of the Anglo-French war of 1294-1303 is the loyalty of the Gascony nobility to the Plantagenet regime. This was in spite of very difficult circumstances: for nine years most of the duchy was occupied by the French, including the chief city of Bordeaux.In their recent works, Kathleen Neal and Patrice Barnabé have argued that this remarkable loyalty was no accident. After his accession in 1272, Edward I spent decades carefully cultivating the loyalty of the Gascons. This was done by respecting local custom – called the 'fors' – and paying every courtesy to the delicate pride and honour of Gascon gentry.

The pay-off came on the outbreak of war in 1294. Of the hundreds of Gascon nobles, only twenty lords or 'seigneurs' defected to the French; virtually all the lesser nobility held for the Plantagenet king-duke. Even in cases where seigneurs changed allegiance, Edward was sometimes able to hold the loyalty of their followers.

One example, highlighted by Barbé, is that of Aiquelm Guilhelm, seigneur of Lesparrre. When the conflict started, Aiquelm was only ten years old. He later claimed to have delivered all of his castles and lands to Edward, but was too young to make such a decision. In reality the transaction was probably handled by his mother, Rose de Bourg, a Plantagenet loyalist: her second husband was the Sire d'Albret, one of Edward's most loyal Gascons, who also fought for the king in Scotland.

It seems the family hedged their bets. When the French invaded their lands, Rose and her brother, Bernard, fled to take refuge on Plantagenet territory. Aiquelm was left behind to welcome the new French castellan. Thus the Guilhelms tried to avoid offending either of the rival kings.

The vacillating attitude of the family was not shared by their followers i.e. the knights and men-at-arms who served in their retinue or 'compagnie'. In 1299, when Edward rewarded his loyal Gascon supporters, a great chunk of fiefs and rents went to over thirty lesser lords of Médoc who belonged to the lordship of Lesparre. These men were vassals of Aiquelm Guilhelm, but – unlike him – had refused to abandon the English cause.

To quote Barbé, Edward had lost the service of the banner-chief, but retained the loyalty of the warriors of his compagnié. As for Philip the Fair, he had gained the not very useful service of one underage Gascon noble with no followers. No wonder the French invasion of Gascony ended in failure.

Published on February 22, 2022 05:10

February 20, 2022

Black Templars and White Templars

Some further digging on mysterious events in Flanders in the early 14th century.

Some further digging on mysterious events in Flanders in the early 14th century.Many of us will be aware of the tradition of the presence of Knights Templar in the Scottish army at the Battle of Bannockburn. Without delving into that, there were certainly a number of Templars serving in the Flemish armies against the French from 1302-3. This was the immediate aftermath of the Battle of the Golden Spurs at Courtrai, where the army of Philip the Fair went down to a shocking defeat.

Philip's first response was to muster a new army, 16,000 strong, and lead it in person into Flanders. The Flemish town militias, principally Bruges, Ypres and Ghent, quickly mustered troops and dispatched them to repel the invasion.

Surviving documents in the city archives at Bruges provide detailed information of the army that participated in this campaign from September-October 1302. It left the town on 30 August and was composed of guildsmen, crossbowmen and small numbers of mercenaries and professional soldiers.

Among the mercenaries were ten knights of Zeeland and their entourage, a few German crossbowmen, a troop of Dutch soldiers and – most interestingly- a band of seven Englishmen. The latter may have been among the original group of 52 English who had served from Christmas-Candlemas 1302, or a separate unit. I suspect these small groups of English soldiers were dispatched in secret by Edward I, as part of a covert agreement with an important Flemish noble, Jean de Renesse.

The document also shows that the town of Bruges paid for wagons and four horses used by 'white Templars', who were led by their captain, Woutier die Grote. The white Templars are described wearing white tunics with red crosses. They served alongside Flemish 'Black Templars' i.e. Hospitallers, who wore black tunics with white crosses. The captain of the Hospitallers was one Hannekin vanden Hulbusche. The Templars formed a band of 13 to 20 men, the Hospitallers had 20 to 30.

The expedition itself lasted 41 days. No battle was fought, but the outcome was an embarrassing failure for the French. Since he had lost so many knights at Courtrai, Philip's men were inexperienced, and he dared not risk an open confrontation. When the Flemish army drew near to Douai on 29 September and prepared to attack, the French retreated. The Flemings gave chase, plundered the French camp and killed a number of stragglers: one Flemish chronicler mentions the loss of 200 French knights and 100 French and Genoese infantry.

On 9 October, after some messy skirmishing, the army of Flanders disbanded and went home. Philip's withdrawal was seen as a disgrace by his French subjects, and he was obliged to make a public statement to explain his action: there had been a shortage of supplies (he claimed) and the Flemings had taken up a strong position, which was difficult to attack. However, he promised to launch another invasion very soon.

Philip would eventually have his revenge on the Flemings, but for the moment he had suffered two humiliations in a row. Although the number of Templars in the Flemish army was small, perhaps their mere presence at least partially motivated his calculated destruction of the order.

Published on February 20, 2022 06:25

February 18, 2022

The hand of the receiver

In July 1302 the feudal host of France was smashed by Flemish urban militia at Courtrai in Flanders, remembered as the Battle of the Golden Spurs. Or, to quote Fiona Watson's recent book on Robert de Bruce, 'the most important battle nobody has ever heard of'.

In July 1302 the feudal host of France was smashed by Flemish urban militia at Courtrai in Flanders, remembered as the Battle of the Golden Spurs. Or, to quote Fiona Watson's recent book on Robert de Bruce, 'the most important battle nobody has ever heard of'.At the time of the battle, Count Guy of Flanders and two of his sons were in French prisons. The regency of Flanders was thus undertaken by another son, Jean, Count of Namur. His regency lasted from the day after the battle until May 1303. During this period, Jean sent envoys to England to try and persuade Edward I to resurrect the Anglo-Flemish alliance, previously agreed between the king and Count Guy. These negotiations were complex. Jean wished to procure English aid not only to protect Flanders, but also his land of Namur, a small county menaced by Holland, Hainault and Zeeland. At the same time a Flemish knight, Jean de Renesse, went to England to gain support for the city of Bruges. His mission lasted between September 1302 and the start of 1303.

Jean de Namur's envoys met with a cold reception. To his request for alliance, the English king and council issued a series of negative responses. First, England and France had been at peace since the truce of 1299; therefore a state of war only existed between France and Flanders. Second, the king had far too many commitments in Scotland and Gascony. Third, Count Guy was in prison and Jean did not have the authority to act in his father's place. Fourth, the pope wished a permanent peace between England and France, which the English dared not put in jeopardy by helping the Flemings.

So the Flemish mission failed. Or at least that was the official line. The separate mission of Jean de Renesse is much more difficult to trace, perhaps for good reason. He went to England to ask military support for the city of Bruges.

Lo and behold, when we sift through surviving Flemish military accounts, what do we find? Between Christmas Day 1302-Candlemas (February) 1303, there was a company of 52 English soldiers in the service of the city of Bruges. They were led by a Flemish officer, Willem de Gand, and paid very good wages of 2 shillings a day per man. Smaller units of English soldiers also turn up in the communal army of Bruges for the following years 1303-04.

These men could have been mercenaries, acting independently of the king. However, the accounts of Jean of Namur for 1302-03 contain a payment of the very large sum of £1320 and 5 shillings. This cash was 'given by hand of the receiver' for the expenses of knights sent to England and Germany. Soon afterwards, we find units of English and German mercenaries in Flemish service.

So, we have what looks like a secret payment, handled by a mysterious 'receiver', who funnelled money to England and Germany to raise soldiers to fight for Bruges against the French. All of this coincided with the trip of Jean de Renesse to England to procure military support for the city of Bruges. His journey coincided with the much more widely publicised mission of the regent of Flanders, Jean de Namur.

The implication is that Edward rejected the Flemish advances in public, but came to a private arrangement with Jean de Renesse. Small units of English soldiers would be sent to Flanders to fight the French. It had to be arranged in secret, because England and France were at peace, and Edward was technically once again a vassal of the French king, Philip the Fair.

Published on February 18, 2022 07:09

February 16, 2022

Then all men died for me.

Margaret of France, Queen of England and second wife of Edward, died on 14 February 1318. I missed the anniversary of her death because I frankly couldn't be bothered: the domestic & family life of ancient royals tends to bore me silly, and I much prefer military, diplomatic and spy stuff. Boy's toys, I guess.

Margaret of France, Queen of England and second wife of Edward, died on 14 February 1318. I missed the anniversary of her death because I frankly couldn't be bothered: the domestic & family life of ancient royals tends to bore me silly, and I much prefer military, diplomatic and spy stuff. Boy's toys, I guess.It doesn't help that Margaret herself is, at first glance, not a very inspiring figure. In his Yale biography of the king, Michael Prestwich remarks that 'she left only a slight imprint on history'. Her most remarkable feat in life was to have a successful marriage with a much older man: Edward was 60 at the time of their wedding in 1299, Margaret just 18.

Margaret is possibly underrated. Recent studies have argued that she wielded considerable influence: during her eight-year marriage to the king, she interceded between her husband and his subjects on sixty-eight occasions. The pardons issued declare that the transgressors were:

“Pardoned solely on the intercession of our dearest consort, queen Margaret of England".

Margaret was also politically aware, and appreciated the pervasive influence of Walter Langton, Bishop of Coventry, whom Edward relied on entirely in the last few years of the reign. In a letter to a clergyman, Richard of Bury, Margaret described Langton as 'the king's right eye in all matters'. Much of her correspondence is untranslated, and may reveal a few more layers to this enigmatic queen.

Another intriguing reference to her is found in Sir Thomas Gray's Scalacronica. Gray describes a curious episode in which Edward deceived his wife by leaving a forged letter on the marriage bed, which stated that her brother, Philip of France, was about to be captured at the siege of Lille in Flanders. Margaret then betrayed her husband by sending the letter to Philip, which frightened him into lifting the siege of Lille and retreating. The story may sound implausible, but Philip did indeed call off an expedition to Flanders in 1302, for no obvious reason.

After Edward's death in 1307, Margaret declared that all men were now dead for her, and withdrew from public life. She commissioned a Latin eulogy for her late husband, written by John of London, which made Edward sound like some kind of superman, still leaping aboard horses and charging about the place in his latter years. In reality he was crippled by illness and had to be carried about in a litter; this was not how Margaret wanted Edward to be remembered, so she spun a false image of him. That's love, folks, or something like it.

Published on February 16, 2022 03:42

February 14, 2022

Anything that mooed or whinnied

In spring 1297 Count Henri de Bar and his lieutenant, the Sire de Blamont, invaded the county of Champagne in north-east France. This was the first action undertaken by Edward I's expensively assembled allies against Philip the Fair of France. For his service, Henri received an initial payment of 10,000 marks on 1 June and an additional £4000 in 1299, among other sweeteners.

In spring 1297 Count Henri de Bar and his lieutenant, the Sire de Blamont, invaded the county of Champagne in north-east France. This was the first action undertaken by Edward I's expensively assembled allies against Philip the Fair of France. For his service, Henri received an initial payment of 10,000 marks on 1 June and an additional £4000 in 1299, among other sweeteners.The county of Champagne was held by Philip's consort Joan, queen of Navarre. Henri's raid may have been intended to divert the French from invading Flanders, but the count also had personal motives. For several years he had been at feud with the abbey of Beaulieu, just over the border from his province of Bar-le-Duc (later the Duchy of Bar) on the frontier of the Holy Roman Empire.

Bar split his forces, taking one part to raid the abbey and dispatching the other, led by Blamont, to attack the French. His forces plundered Beaulieu, burnt the abbey, treasury and archives, as well as the adjacent village: fragmentary surviving accounts record the burning of dozens of 'hearths' or homesteads. He also carried off the bones of a local saint, to be re-interred inside one of his own churches.

Meanwhile Blamont ravaged Champagne, torching villages and storming at least two fortified towns and castles, at Andelot and Wassy. When Philip was alerted to the invasion, he sent his seneschal, Gercher de Cressy, to counter-attack and invade Bar, forcing Henri and Blamont to turn back to defend their own lands. The French destroyed a number of vills and small fortresses along the frontier of the Barrois, and then withdrew to Champagne.

The conflict on the franco-imperial borderlands caused a great stir. A contemporary French soldier-poet, Guillaume Guart, described the French counter-raid on the Barrois in his verse chronicle:

“He turned to attacking it, burning villages and seizing livestock – anything that mooed or whinnied – and despoiling trees and vines of timber, of leaves and of bark, so that by sheer necessity the count, scarcely delaying, was obliged to come there to defend his land...”

When Edward I heard of his son-in-law's action, he quickly dispatched a letter to Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany, urging him to bring up German troops in support of the attack on Champagne. Adolf responded by trekking up and down the western imperial borderlands, using English money to recruit military allies among his vassals. Though willing, he was unable to take affective action against the French until September.

Even so, plenty of damage had been done. Decades later, Philip's tax officers were still trying to work out ways of paying for the devastation. In the end they imposed a special subsidy on the people of Champagne, calculated at a total assessment of almost 100,000 livres tournoise (roughly – if my calculations are correct - £30-£40,000).

The raid was also useful for propaganda purposes. In the summer of 1297, shortly before Edward sailed for Flanders, copies of a newsletter were sent all over England, explaining the king's reasons for war against the French. A version of the newsletter survives, pasted into the Chronicle of Hagnaby. Apart from listing Edward's allies in Flanders and the Low Countries, it also highlights the Count of Bar's invasion of Champagne earlier in the year. This was perhaps meant to show that the king's massive expenditure was not in vain, and the strategy of attacking the French on all fronts had started to bear fruit.

k here to edit.

Published on February 14, 2022 07:36