David Pilling's Blog, page 8

February 12, 2022

Sorrow and suffering?

“There was much sorrow and suffering on both sides, as they quarrelled and fought”

“There was much sorrow and suffering on both sides, as they quarrelled and fought” - Lodewijk van Velthem

In February 1298 there was a serious riot at Ghent in Flanders, where the Welsh and English soldiers of Edward I fought a battle in the streets against the Flemish citizenry. The various chronicles report severe damage and loss of life, although as usual it is difficult to untangle facts from distortion.

The king had moved his army to Ghent the previous September. From the start, there were problems. Flanders was divided politically between pro and anti-French elements, and a great number of Flemings had abandoned their ruler, Count Guy, to fight for Philip the Fair. Shortly after Edward's arrival at Ghent, tensions exploded between his men and the citizenry. When he rode through the gates, the king was almost shot dead by a Flemish assassin. The crossbow bolt hit one of his knights instead. In a rage, Edward ordered his Welsh infantry to fire the streets.

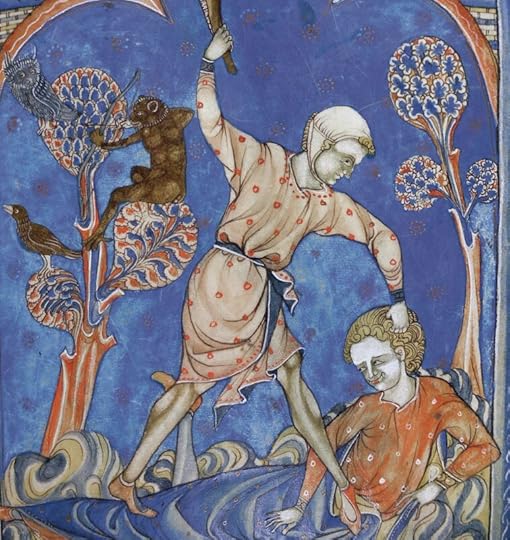

A riot blew up, in which the Welsh distinguished themselves: one earned a bounty of £5 from the king for swimming across the river to rescue an English comrade, who was about to be killed by two Flemings. More Welsh got inside Ghent by wading across the streams, climbing the wall and burning the gates from the inside.

The riot was quashed, but resentments simmered. In February, after making a truce with the French, Edward went to Brabant to secure the English wool staple from his son-in-law, the duke. While he was gone, the Welsh and English infantry grew bored and started to abuse the citizens again. Seeing their homes destroyed and wives and daughter raped, the menfolk of Ghent had no choice but to take up arms.

Or at least, that was the version of events in Flemish sources. The major English source, the Chronicle of Bury St Edmunds, claims the people of Ghent had entered into a conspiracy with Philip. On the Feast of Blaise (11 February) they planned to butcher Edward's soldiers, seize the king himself and hand him over to the French. Their plan was foiled when the Welsh lodged in the suburbs outside Ghent burnt through the gates (these were very flammable gates), fell upon the conspirators and slaughtered then. Edward himself joined in and charged the Flemish artillery at the head of his household knights.

Flemish sources claim the Anglo-Welsh suffered terrible casualties and Edward had to beg the citizens to let him and his men leave the city. English sources claim the Flemings suffered terrible casualties and had to beg Edward's mercy. And so on.

Away from the lies and finger-pointing of chroniclers, the surviving accounts paint a less dramatic picture. On 24 February privy seal writs were drawn up in Ghent, sent to England to request safe-conduct for Welsh troops that had already been shipped back to England. On 11 March the chancery issued letters for the men of Glamorgan, with further letters on 15 March for the men of north and west Wales. One final batch of letters, for a group of five stragglers, was issued on 27 March.

Far from suffering casualties, the Welsh appear to have been ferried home, more or less intact. Their officers – Gruffudd Llwyd, Robert Veel and Morgan ap Maredudd – were certainly alive and well. The only named Welsh 'casualty' was one Llywelyn Goly, paid travel expenses by the king to go home on account of 'infirmity' i.e. he had fallen sick.

Not that the riot itself should be dismissed as a myth. In early March 1298, after Edward had moved his headquarters from Ghent to Aardenburg, he gave orders for compensation to be paid to the merchants of Ghent. This was on account of the injuries done to them by the king's soldiers. In addition, a fragment of a wardrobe account records that Welsh troops had stolen grain from mills outside the city. These details suggest a bunch of very drunk medieval squaddies indulging in a spot of looting – not exactly uncommon behaviour, then or now.

Published on February 12, 2022 05:51

February 10, 2022

There's been a murr-derrr

On this day in 1306 Robert de Bruce murdered his rival, John Comyn, at Greyfriars in Dumfries. Comyn's uncle, Robert, was also killed as he tried to defend his nephew. I thought it worth taking a quick look at John 'the red' Comyn, perhaps one of the most unjustly vilified figures in the history of medieval Scotland.

On this day in 1306 Robert de Bruce murdered his rival, John Comyn, at Greyfriars in Dumfries. Comyn's uncle, Robert, was also killed as he tried to defend his nephew. I thought it worth taking a quick look at John 'the red' Comyn, perhaps one of the most unjustly vilified figures in the history of medieval Scotland.These days John is often presented as a traitor to the cause of Scottish independence. Or at least, that is how he presented in cinema and on some disturbingly popular social media groups. This appears to be the direct result of centuries of Bruce propaganda and the unwillingness of modern generations to question national heroes.

The popular version goes something like this: Bruce was a steadfast, patriotic hero who never bowed the knee to the foul tyrant, Edward Longshanks. Comyn, by contrast, was a cowardly quisling who betrayed William Wallace at the battle of Falkirk and later surrendered to Longshanks on very easy terms. Bruce was right to kill him, even if the circumstances were a bit dodgy.

The reality was this: from the very start of the Scottish wars in 1296, Comyn was consistently opposed to the English. In that year he was among those who invaded England and attacked Carlisle, which the Bruces were defending on King Edward's behalf. A few weeks later Comyn and many others were captured at the battle of Dunbar. In 1297 he was released in exchange for doing military service in Flanders, but deserted the English host when Edward shifted his headquarters from Ghent to Aardenburg, near the Zeeland border.

For the next seven years Comyn was one of the leading lights of the Scottish resistance. His presence at Falkirk in 1298 is uncertain, but it cannot be said that any of the Scottish principals covered themselves in glory: Wallace fled the field and left his men to die, Bruce was conspicuous by his absence, and Simon Fraser fought on the English side.

After Falkirk, Comyn and his fellow Guardians adopted a new strategy, whereby they evaded battle and retook castles and territory when the opportunity arose. Comyn was a supporter of the exiled King of Scots, John Balliol, and for a while it seemed that Balliol's return, backed by a French army, was very much on the cards. That possibility was shaken when Philip the Fair reneged on the Treaty of Asnieres in 1302, and went up in smoke completely when the French suffered a shock defeat at Courtai in Flanders.

The Scottish strategy worked well for as long as Edward was distracted elsewhere. However, when he made a final peace with France in 1303, the English king was able to focus all his resources for one last push in Scotland. Comyn's efforts to repel the onslaught were nothing short of heroic. In February 1303 he won a morale-booting victory at Roslin over Sir John Segrave. More significantly, when the king took his army over the Forth to ravage northern Scotland, Comyn and Wallace attempted a clever counter-strike into northern England. The ploy failed, but it was a near thing. Bruce, meanwhile, was actively fighting for the English.

At last Comyn agreed to open peace talks. This was due to several factors: for the first time since 1296, Edward had managed to hold his army together long enough to maintain an effective presence in Scotland. He could not be shifted, at least in the short term, so it made sense to come to terms. Besides, Edward was old and in poor health, and the Guardians may have gambled on an armistice in the knowledge that their chief enemy was not long for this world.

Finally we come back to 10 February 1306, and a wee dispute in a church. Bruce's motives have been discussed at length elsewhere: among other motives, he was probably alarmed by the rise of the Comyn faction in Scotland, which threatened his own ambitions. So, as Taggart might say, there was a murr-derrr.

(The image is of Jared Harris as John Comyn in the 2019 movie Robert de Bruce)

Published on February 10, 2022 05:32

February 9, 2022

Look stupid, act crafty

In early 1303 the duchy of Gascony was restored to the English, after the French had occupied much of the territory for the past nine years. This was the end of the Anglo-French war between Edward I and Philip the Fair, a hugely expensive conflict that ended in a return to the status quo, as if nothing had happened.

In early 1303 the duchy of Gascony was restored to the English, after the French had occupied much of the territory for the past nine years. This was the end of the Anglo-French war between Edward I and Philip the Fair, a hugely expensive conflict that ended in a return to the status quo, as if nothing had happened.

In terms of finance, a great deal had happened, and none of it good. During the war Edward done his best to send help to the Gascons, and regarded the recovery of Gascony as central to his honour. He said as much in a letter to the council in London, dated 16 October 1297:

“For our honour or dishonour lies in this business, and that of all those who love us...”

The cost of upholding the king's 'business' was immense. By 1303 Edward's finances were in a state of total confusion, thanks to the constant drain of wars in Gascony, Flanders, Wales and Scotland. After the restoration of Gascony, the king sent two of his most trusted servants, Othon Grandson and Henry de Lacy, to patch up the tottering administration.

Their first task was to settle the king's many debts to his Gascony subjects. These were almost all for direct loans made to Edward during the war, including payments of back wages and compensation for damages suffered in the fighting. The largest debt was to the men of Bayonne, who had lent the king the staggering sum of £45, 763, 14 shillings, 1.5 pence: the penny-halfpenny shows they meant to recoup their money down to the very last bit of metal.

Other considerable debts included £2000 owed to John of Brittany, the king's nephew, and £20 owed to the bailiff of the Isle d'Oléron, who had no money to buy grain or wine, or even pay for a ship to take him home. There was also a great stack of debts owed for horses killed during the war: one was described by an absent-minded clerk as 'bay, with one eye and four white forefeet'.

With a touch of old-fashioned chivalry, Edward had distributed food to the people of Gascon towns, and spent over £400 for sixty cloths to make dresses for impoverished Gascon ladies. He had even pawned some of the crown jewels for £2250 and pledged a major source of revenue, the export duty on wools, to help offset the massive debt to Bayonne.

The king was partially helped out of his difficulty by those ever-obliging Italian banking houses. One of them, Giovanni de Frescobaldi, composed a sonnet titled 'memorandum for anyone crossing to England'. This was a piece of satirical business advice for anyone who did business with the English:

'Wear quiet clothes, be humble; look rather stupid but act craftily. Spend generously so that you do not seem mean, pay your bills as you go, and buy things up ahead of time if it seems advantageous. As for collecting your debts, make your request nicely, and explain that you are compelled to so do only by extreme need. Do not get into trouble nor ask unnecessary questions, do not get involved with courtiers, stay on good terms with the other Florentines, and be sure to lock your doors, just in case'.

Published on February 09, 2022 06:00

February 7, 2022

Fall Guy

In February 1298 the envoys of England and France met at Tournai, now a city in western Belgium, to hammer out peace talks. This was the final round of negotiations after a series of short truces between the rival kingdoms, first struck on 9 October the previous year.

In February 1298 the envoys of England and France met at Tournai, now a city in western Belgium, to hammer out peace talks. This was the final round of negotiations after a series of short truces between the rival kingdoms, first struck on 9 October the previous year.The talks were encouraged by two papal legates, the generals of the Franciscan and Dominican orders, who had come to enforce Pope Boniface VIII's request that both Edward I and Philip the Fair lay their grievances before the Curia. It suited neither king to continue open hostilities, so they agreed to papal arbitration.

From an English perspective, the Tournai agreement was really a means of disengaging from the futile war on the continent. Not that Edward simply abandoned his allies, principally Count Guy of Flanders. As per the previous truces, Guy and the other members of the so-called Grand Alliance against France were included in the armistice.

In the short term, the Tournai agreement preserved what remained of independent Flanders until the expiry of the truce in January 1300. Philip kept his territorial gains, including Lille and Bruges, while Guy was left with Douai, Ypres, Damme, Ghent, the Waas country between Antwerp and Ghent, and the region of Quatre-Métier. Guy only retained this much because German troops in English pay had defended Ypres against the French, while Damme was recaptured by a combined force of English, Welsh and Flemings.

Philip, for his part, was content to wait until the expiry of the truce before resuming his conquest of Flanders. He knew that Edward was too preoccupied elsewhere to send Guy further material assistance, and so it proved. When Guy sent desperate letters to Edward in the following months, complaining of breaches of the truce, the English king's responses were lukewarm. This was now a matter for the pope, Edward explained politely, though he was happy to send a letter to Rome if Guy thought that would help.

Guy needed troops and money, not words. Edward was embroiled in his wars in Gascony and Scotland, and the Count of Flanders found little support elsewhere. When his sons complained to the pope, Boniface threatened to cut Guy adrift completely. The harsh reality was that England and France were greater powers than Flanders, and peace between kings came first.

Spurned by Edward and the pope, Guy looked desperately for support elsewhere. All he found was the cold shoulder. The King of Germany, Albert of Hapsburg, rejected his advances, as did the young Count of Holland. Guy was no longer of any use to anybody, and there are no true friends in politics.

When the French resumed their offensive in 1300, Guy and his supporters were hopelessly outnumbered. Philip's armies quickly overran Flanders and took Guy prisoner. In 1302 he was briefly released to negotiate terms with his former subjects, but then returned to captivity. Now in his sixties, the defeated old man died in custody on 7 March 1305.

Published on February 07, 2022 02:56

February 5, 2022

The trials of Burst-Belly

Today is the anniversary of the death of Henry de Lacy, earl of Lincoln (c.1251-1311), also Baron of Pontefract, Lord of Bowland, Baron of Halton and hereditary Constable of Chester.

Today is the anniversary of the death of Henry de Lacy, earl of Lincoln (c.1251-1311), also Baron of Pontefract, Lord of Bowland, Baron of Halton and hereditary Constable of Chester.A man who inherited such power and wealth was destined to play a major role in politics. Lacy became one of chief councillors of Edward I and was one of a tight group of loyalists who always supported the king, even in years of crisis. He was frequently entrusted with military commands and served Edward in Wales, Scotland and Gascony.

Lacy was perhaps distinguished more for his loyalty than military ability. He suffered two bad individual defeats, at Denbigh in North Wales in 1294 and Bellegarde in Gascony in 1297. On both occasions he appears to have walked into an ambush, though the chronicles hint of treachery at Bellegarde. Neither defeat was fatal to the English cause, and Lacy retained his master's confidence.

Perhaps Lacy's most impressive achievement was his term as seneschal or 'capitaneus' of Gascony from 1296-98, when much of the duchy was under French occupation. After the death of Edmund of Lancaster, Lacy took command of the outnumbered Anglo-Gascon army and managed to cling onto the remaining territory until a truce was struck with the French. Whatever his faults as a soldier, Lacy turned out to be a skilled administrator, and held together the English war effort despite a lack of money and resources.

On the debit side, Lacy was a harsh and oppressive landlord. His governance of the new Marcher lordship of Denbigh, carved out after 1282, was grimly exploitative: the earl's officers destroyed Welsh settlements to make way for his deer parks and stud farms, forcing the tenantry to go and live on bleak upland areas, where they could barely scratch a living. This cruel treatment provoked the revolt of 1294, where Lacy suffered an embarrassing defeat at the hands of his own tenants.

The earl's loyalty to the crown was not unquestioning. He was one of the first to protest at the rule of the new king, Edward II, and his favourite Piers Gaveston. According to later accounts, Gaveston gave Lacy the unkind nickname of 'Burst-Belly', after his protruding stomach. In his last years Lacy joined Thomas of Lancaster and the party of 'Ordainers', who in 1311 imposed a series of restrictions on the king. He died in the same year, before Edward could take his revenge.

There was probably a bit more to Lacy than a stolid, unimaginative feudal magnate. He and Walter of Bibbesworth, an English soldier-poet, composed a poem or 'tenson' about crusading, La pleinte par entre missire Henry de Lacy et sire Wauter de Bybelesworthe pur la croiserie en la terre seinte.

Published on February 05, 2022 05:37

February 4, 2022

Trailing bastons

Trailing bastons.

Trailing bastons.The 'trailbaston' commissions were set up in the troubled last decade of Edward I's reign, ostensibly to deal with a crime wave in England. This was the result, supposedly, of the wars in France and Scotland that had destabilised law and order in England.

Some modern historians have argued that trailbaston was really a device to make money, rather than a reaction to increased crime. This interpretation is based on the notion that Edward needed to refill his depleted coffers, and so exaggerated the crime rate in order to introduce heavy financial penalties for offenders.

In her recent works, Caroline Burt has argued persuasively that the king was right to be worried. Edward himself described the state of disorder in England as being like the start of 'civil war', and the steep rise in business in King's Bench from every county in England speaks for itself.

What really happened was this. After the end of the Scottish war in 1304, Edward was once again able to focus on domestic government. He and his legists turned to the problem of gangs of malefactors – most of them ex-soldiers – who were wandering from place to place in England, killing and robbing at will. For instance, a commission issued at Newcastle in August 1303 speaks of 'vagabonds in league' committing 'depredations at night' and 'refusing to submit to justice'. The 'trailbaston' commissions themselves were named after the heavy clubs or 'bastons' that the robbers carried with them, literally trailing on the ground.

These new commissions had the power to investigate all felonies and trespasses committed in England since 1297. The most radical innovation was to prosecute offenders even if no private accuser could be found: this was unprecedented, and intended to prevent the intimidation of plaintiffs. As Burt said:

“It was clearly intended that there would now be no hiding place for those who had, as the king himself wrote angrily, flouted his lordship and whose outrages were like the beginning of civil war'.

In the short term at least, trailbaston was effective. In the last years of Edward's reign the crime rate plunged in most of the counties, although in some places it went up again soon after the succession of the new king, Edward II. The key problem was that too much depended on the person of the king: if he was distracted by external wars, or disputes at court, he could not give sufficient personal attention to law and order. This, however, was a fundamental issue of medieval kingship that no clever legal systems could fix.

Published on February 04, 2022 03:50

February 3, 2022

Casus Belli

In February 1303 a party of English envoys crossed the Channel and went to Paris, to begin talks over the return of Gascony to Edward I. The envoys were three of the king's most trusted men; Count Amadeus of Savoy, Henry de Lacy, and Othon Grandson.

In February 1303 a party of English envoys crossed the Channel and went to Paris, to begin talks over the return of Gascony to Edward I. The envoys were three of the king's most trusted men; Count Amadeus of Savoy, Henry de Lacy, and Othon Grandson.This negotiation marked the end of a nine-year conflict, possibly the most futile of all Anglo-French wars. Because it was relatively bloodless, the war had proved massively expensive for both kingdoms. The actual fighting had petered out in 1297, but that was not the end of it: in the six years of uneasy truce that followed, garrisons and fleets had to be maintained, soldiers paid, castles and towns kept in a state of readiness. Hostilities could have flared up again at any time, and neither side wanted to be caught napping.

English and French historians have puzzled over Philip the Fair's decision to trigger a war over Gascony. He was already overlord of the duchy, via the Paris agreement of 1259, and Edward was careful to toe the line of feudal subordination. Preoccupied with affairs inside the British Isles and Ireland, the very last thing he needed was a war with France. In the end, since he could not provoke a war, Philip was obliged to invent a 'casus belli' by simply breaking his word to the English king's brother, Edmund of Lancaster. His decision was part of Philip's aggressive imperialist policy, in which he sought to expand the borders of Capetian France in all directions at once.

The recovery of Gascony was a messy process. One of the many bones of contention was the status of the chief city, Bordeaux. In January 1303 the citizens had staged a coup and driven out the French garrison. This meant they were in revolt against Philip, and technically in revolt against Edward as a vassal of France: or at least they would be, when Edward's proxies re-swore the oath of homage and fealty to the French crown. The oath was a necessary step in restoring the pre-war feudal arrangement, which was tantamount to admitting that the war had, effectively, never happened.

Since Bordeaux was barred to the French, the official ceremony of restoration had to take place at St Emilion. Henry de Lacy, earl of Lincoln and former English seneschal of Gascony, acted for his royal master. The haggling rumbled on until a final treaty was struck at Paris in May, whereby the duchy was restored to the English in full.

Published on February 03, 2022 04:35

February 2, 2022

A carve-up at Koblenz

On February 1297, the allies of Edward I met at Koblenz, a German city on the banks of the Rhine. Those present include Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany and titular Holy Roman Emperor, the nobles of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgundy, and Edward's son-in-law, Count Henry of Bar.

On February 1297, the allies of Edward I met at Koblenz, a German city on the banks of the Rhine. Those present include Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany and titular Holy Roman Emperor, the nobles of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgundy, and Edward's son-in-law, Count Henry of Bar. This meeting was a precursor to the combined military campaign against Philip the Fair of France. After a delay of three years, the allies were finally ready to go into action. Their strategy was to attack the French on all sides and stretch Philip's forces to breaking point. This was most likely copied from the strategy of King John and his allies back in 1214, which had ended in disaster at Bouvines.

The German king, Adolf, had received English subsidies to fund the war. He had spent much of the cash on a private war inside the empire, but enough remained to fund the nobles gathered at Koblenz. He also formally disinherited those lords of Burgundy who had joined the king of France, and re-granted their forfeit land to Edward's allies. For instance, he gave the Count of Bar the fiefs that Guy de Jonveille had held of the Count of Burgundy, and those confiscated from Jean de Bourgogne as far as Conflans in the châtellenie of Vesoul. Tit-for-tat, Philip seized Bar's townhouse in Paris and responded to the Koblenz assembly by confiscating the land of Toucy and all that the count possessed in the provostry of Paris, to give to Charles de Valois.

Adolf also promised to take back as direct fiefs of the empire certain lands they had previously held of the Count of Burgundy, who had joined Philip. The lords of Franche-Comté also obtained Adolf's promise of military support against the French, in return for which they pledged to lay their castles open to him and act as his vassals. Adolf vowed to bring his troops to Burgundy before 22 July, and in the meantime granted them subsidies in advance. They were also given leave to enter King Edward's service on the same terms as they served the emperor.

Finally, after all this cash and soil had been distributed, the pieces were in place. After years of haggling and horse-trading, the great game of war was set to kick off...

Published on February 02, 2022 03:35

February 1, 2022

Psychological concepts

Today is the anniversary of the coronation of Edward III. Praised by his contemporaries, damned by post-1800 historians as a warmonger, Edward received the following epitath after his death in 1377:

Today is the anniversary of the coronation of Edward III. Praised by his contemporaries, damned by post-1800 historians as a warmonger, Edward received the following epitath after his death in 1377:"Here is the glory of the English, the paragon of past kings, the model of future kings, a merciful king, the peace of the peoples, Edward the third fulfilling the jubilee of his reign, the unconquered leopard, powerful in war like a Maccabee. While he lived prosperously, his realm lived again in honesty. He ruled mighty in arms; now in Heaven let him be a king".

These days Edward gets a relatively good press: certainly more so than his grandfather, Longshanks, though for my money they were essentially the same person. By the standards of his own time, Edward was successful for much of his reign, but his last few years were pitiful.

By our standards, nobody really seems to have a clear definition of a 'great' medieval king. We don't like war, apparently, and yet the likes of Robert de Bruce and Joan of Arc are still regarded as heroes. To apply moden progressive virtues to rulers who died hundreds of years ago is obviously absurd. As Michael Prestwich pointed out, medieval minds were not cluttered with psychological concepts: it never occured to them to ask if a king was clever or stupid, original or derivative, or even if he had powers of leadership, in the sense that we understand them. It's a wee bit of a problem.

Published on February 01, 2022 07:43

The King marvelled very much...

In early 1298 Duke John II of Brabant granted the city of Antwerp and adjoining towns to his father-in-law Edward I of England. This was in the aftermath of the war in Flanders, which ended in a series of annually renewed truces between England and France.

In early 1298 Duke John II of Brabant granted the city of Antwerp and adjoining towns to his father-in-law Edward I of England. This was in the aftermath of the war in Flanders, which ended in a series of annually renewed truces between England and France.Edward used the truce to enforce English mercantile interests, particularly the wool trade. The text of the 1298 charter explicitly states that the margraviate or march of Antwerp was to be held by King Edward and his heirs in perpetuity. It also carefully lists all the rights handed over to the English: the rents, lands, fiefs, homages, justices, rights, profits etc. It appears the anglophile duke had permanently surrendered a large chunk of Brabant to the king of England.

Why would he do this? In 1294, at Llanfaes in North Wales, the duke contracted to do military service for Edward against the French. This was in exchange for a fee of 200,000 livres tournois (roughly £50,000). To put the sum into context, that was over half the total cost of the famous Edwardian castles in Wales.

Apart from the fee, there were logistical problems in conveying such a huge sum of money. It had to be shipped overseas in instalments, running the gauntlet of French privateers, and then carried across land to Brabant. In exchange for all this effort and expense, Edward expected the duke to provide military assistance when the English landed in Flanders in August 1297. Duke John did not disappoint and joined the Anglo-Welsh army at Ghent, where he was knighted by his father-in-law. His arrival is described in the chronicle of Lodewijk van Velthem, a Flemish priest:

“The Duke of Brabant was also there

with many men, as you should know,

from his land, and also with many

from the borders of the Meuse, many a lord,

and also from the Rhine”.

Edward also needed to recoup his financial investment. After patching up a truce with the French, he went to Brabant to make John a mutually profitable offer. The duke, called John the Peaceful by his subjects, was not inclined to argue. Antwerp was also, not coincidentally, the centre of the overseas English wool trade. In 1296, as part of the deal struck at Llanfaes, Edward had moved the wool staple from Dordrecht in Holland to Antwerp.

The king's visit to Brabant is also recorded by van Velthem:

'Not long after this was done,

the King travelled to Brabant,

to visit his daughter [wife of the Duke] and also the country.

He came in Brussels with much honour.

There he received the Lords well.

He closely inspected the town

and amused himself and conversed.

There were certainly many Counts,

who all were vassals of the Duke;

the King marvelled very much

that so many a Lord held his lands from him [the Duke].

About this the King was much pleased,

because before he had not thought

that Brabant had been that large.'

Duke John welcomed the increased trade with open arms, and in the same year issued a charter granting exclusive trading rights to English wool merchants. This charter was renewed at Brussels in 1305, whereby English merchants in Antwerp practically became a self-governing community.

Published on February 01, 2022 04:46