David Pilling's Blog, page 11

December 31, 2021

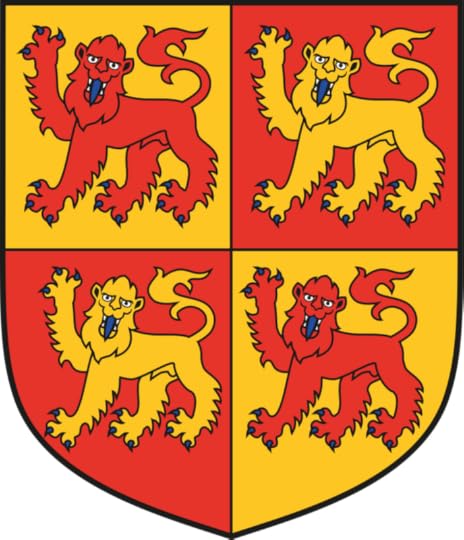

The Red Earl

'Richard de Burgh, at the instance of the sons, took into his hands all William's lands in Ulster held of the king in chief, and seized and destroyed the chattels found therein'.

'Richard de Burgh, at the instance of the sons, took into his hands all William's lands in Ulster held of the king in chief, and seized and destroyed the chattels found therein'.- Calendar of Documents for Ireland, 1252-84

In 1280 Richard de Burgh came of age as Earl of Ulster. The emergence of the 'Red Earl', as he was known, changed the course of the civil war that had raged inside Ulster during his long minority. De Burgh appointed Thomas de Mandeville as seneschal of Ulster, and threw his power behind the Mandeville-O Neill faction against their enemy, William Fitz Warin.

A later enquiry revealed how the earl and his Anglo-Irish allies had conspired against William. First they mounted a raid on his lands and seized goods worth £600. When William demanded them back, he only received the value of £64. He then asked for, and got, a letter from de Burgh ordering the rest of the goods to be returned.

So, armed with his letter, William went from Dublin into Ulster and asked Thomas Mandeville to hand over the goods. Thomas agreed, and asked William to meet him on a certain day to complete the transaction. All and well good. Lovely. No problem.

Yeah, right. On the appointed day and place Thomas Mandeville turned up with a band of heavies in tow, including a large number of Irish warriors: Moriachan O'Flynn, Brian O'Flynn, Gillecondil O'Conul and their men, among others. Their purpose was to seize William and drag him off to prison.

Somehow William got wind of the plot, and threw himself on the mercy of the sheriff. However the sheriff refused to protect him unless William could obtain a writ from the Chancery in Dublin: this was a hell of a thing to ask of man being chased about the countryside in fear of his life, and implies my lord sheriff was thinking of his own skin.

The seneschal, Thomas Mandeville, now ordered all ports and roads in Ulster to be closed. It seemed William was trapped, but he had one friend left in the shape of MacCartan, lord of South Down, who gave the fugitive refuge in his castle. When the heat had died down a little, William escaped back to Dublin via the pass of 'Imberdoilan', and there begged mercy of the royal council.

As it happened, the council was led by one Nicholas Taf, a follower of Richard de Burgh. Despite his allegiance to the earl, it seems Taf took pity and ordered an enquiry, which discovered that William had done nothing wrong and should not be imprisoned or generally molested. The enquiry also found that William's enemies had pillaged and ravaged his lands without mercy, slaughtered the Irish and English tenantry alike, and carried off his goods, livestock and money.

The war then drifted into a series of lawsuits, but William (for the moment) was at least safe from being killed or imprisoned out of hand. To judge from the record, he owed this deliverance to Nicholas Taf, who suffered no obvious punishment at the hands of the red earl. Taf would go on to become the Justice of the Common Pleas at Dublin.

Published on December 31, 2021 05:33

December 28, 2021

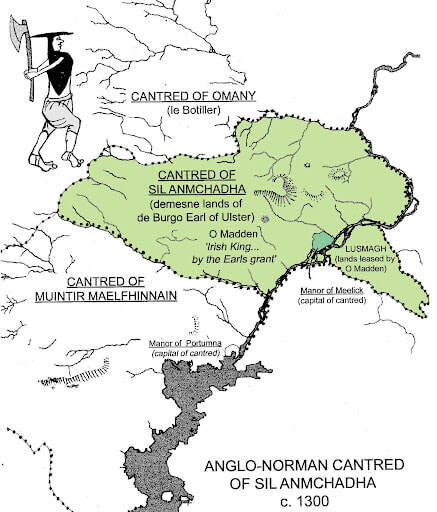

Divers petty kings

In 1272 the Irish lords of Ulster were summoned to take part in a private war between two Norman overlords. On one side was the new justiciar of Ireland, Maurice fitz Maurice FitzGerald and his ally, William FitzWarin. On the other was Henry de Mandeville, the former seneschal of Ulster and a partisan of the de Burghs.

In 1272 the Irish lords of Ulster were summoned to take part in a private war between two Norman overlords. On one side was the new justiciar of Ireland, Maurice fitz Maurice FitzGerald and his ally, William FitzWarin. On the other was Henry de Mandeville, the former seneschal of Ulster and a partisan of the de Burghs. The Irish might have been tempted to let the Normans wipe each other out, but it wasn't as simple as that. They owed homage and military services, and the war presented an ideal opportunity to destroy their own rivals.

Aodh Buidhe O Neill, king of Tir Eoghain, chose to deal with an Irish enemy first. He and another local king, Eachmharcach O Hanlon, combined to destroy Eachaidh MacMahon, king of Oirghialla, a territory that covered parts of modern-day Armagh, Monaghan and Louth. This battle is briefly referenced in the annals of Connacht:

“Eochaid Mac Mathgamna, king of Oriel, was killed, with many others not enumerated here, by O hAnluain and the Cenel Eogain this year.”

The reasons for the killing of MacMahon are unclear, but it was probably meant to clear the way for Aodh and O Hanlon to expand their own interests. Their second task was to exploit the war in Ulster between Fitz Maurice and Mandeville.

Aodh threw his weight behind Mandeville. O Hanlon chose to support the new seneschal, FitzWarin, who was also joined by Aodh's brother, Niall. Thus the Norman war in Ulster caused former alliances among the Irish to dissolve. and turned kindreds upon each other.

O Hanlon and Niall were also aware of the need to gain support from the new king, Edward I. Edward himself was still overseas, so the allies sent a joint letter to the regency council at Westminster. They claimed to have defeated the 'rebels' – Mandeville and his supporters – and to have attacked Mandeville's Irish supporters. However, they had enemies within the royal council of Ireland, who were trying to 'oppress' them. They begged the king to punish these evildoers and write to the seneschal, assuring him of the loyalty of O Hanlon and Niall.

It seemed that Aodh had backed the wrong horse. Sometime in early 1273, Mandeville was killed by FitzWarin, probably in a skirmish. However, Mandeville's sons took up the sword, and the war dragged on. They and Aodh were able to lean upon the influence of the de Burgh faction, who had powerful friends at court.

FitzWarin, described by the Bishop of Waterford as a good soldier but incompetent bailiff, found himself put on trial for Mandeville's death. He was ultimately acquitted, but his Irish allies saw which way the wind was blowing. Shortly afterwards O Hanlon changed sides, which meant he and Aodh were friends again.

A temporary ceasefire was brought about by John de Verdon, the Norman lord of Coolock in the Pale. He wrote to London, informing the regents that he had 'spent much money' in drawing Aodh O Neill to the king's peace. In other words, he had bribed the Irishman to stop fighting.

Interestingly, in his letter Verdon remarks that Aodh was styling himself 'King of all the Irish of Ireland'. Aodh had earlier conspired to destroy his kinsman, Brian O Neill, who claimed the title of High King. It appears he had his own claim to supreme power over the Irish, although Verdon was not convinced. He told the council that, in spite of his grand pretensions, Aodh was just one of many 'divers petty kings' of Ireland.

Published on December 28, 2021 04:52

December 27, 2021

Peace in the Marches

On 14 April 1260 Brian O Neill, Ardi Ri or High King of Ireland, was killed in battle at Drumderg by an army of his own kin and some of the 'foreigners' or Anglo-Normans.

On 14 April 1260 Brian O Neill, Ardi Ri or High King of Ireland, was killed in battle at Drumderg by an army of his own kin and some of the 'foreigners' or Anglo-Normans.A fifteenth century poem claims that a certain Aodh Buidhe had accused Brian of being a usurper, and played a major role in his downfall. This Aodh was a grandson of Aodh Méith O Neill, King of Tir Eoghain (Tyrone) in the early 13th century.

The surviving exchequer accounts reveal that Aodh was in the pay of Lord Edward, who had been granted Ireland by his father, Henry III. The accounts for 1261-2, not long after the battle of Down, show that Aodh was retained in Edward's service 'for keeping peace in the marches of Ulster' and received a wage of £10.

Aodh was an ambitious man. When in 1263 King Henry revived the earldom of Ulster and granted it to Walter de Burgh, Aodh married de Burgh's cousin and accompanied the earl on an invasion of Tir Conaill. However, the earl kept his new ally on a tight rein. In 1269, after an attempted defiance, Aodh was fined 3500 cows and had to surrender four hostages to de Burgh. He was also forced to agree to a humiliating treaty, whereby:

“If I break the terms of our agreement, the lord earl is entitled to expel me from the kingship, which I ought to hold from him, and to bestow it upon whomsoever he pleases, without opposition or vengeance from me or mine”.

When Walter de Burgh died in 1271 and left only a minor as heir, the earldom was once again taken into royal custody. Aodh, along with certain other Irish lords, came to make their submission to the royal justiciar of Ireland, stayed with him a while and were presented with 'robes, furs and saddles'.

The justiciar was James Audley, a baron of the Welsh March. He took the very unusual step of granting the homage of Aodh and his fellows to Aveline, Walter de Burgh's young widow. These homages should have been granted to the crown until the young earl came of age, but Audley was a de Burgh partisan. For good measure, he also granted the post of seneschal of Ulster to Henry de Mandeville, a prominent Burgh vassal.

Audley then helpfully fell off his horse and broke his neck. He was succeeded as justiciar, in August 1272, by Maurice fitz Maurice FitzGerald. FitzGerald hated the Burgh faction and promptly overruled all of his predecessor's decisions. The result was civil war inside Ulster, which left Aodh and the Irish with an interesting dilemma.

Published on December 27, 2021 05:06

December 21, 2021

One or the other

'Nor did they wish to obey Lord Edward, the son of the king, but they laughed boisterously and heaped scorn upon him. And so consequently Edward put forward the idea that he should give up these Welshmen as unconquerable.”

'Nor did they wish to obey Lord Edward, the son of the king, but they laughed boisterously and heaped scorn upon him. And so consequently Edward put forward the idea that he should give up these Welshmen as unconquerable.”- Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora

This is from Paris's account of Henry III's expedition to North Wales in summer 1257, whereby the king tried to shore up his position after a year of military disasters.

I'm usually sceptical of Paris, but his assessment of Edward's attitude has the ring of truth. At this stage Edward showed little interest in Wales, and was much more focused on Gascony and Chester. These formed part of the massive grant or appanage given to him by his father in 1254.

The prince may well have taken the attitude that Wales was a quagmire. In 1247, after two years of grinding warfare and colossal effort and expense, his father had imposed the Treaty of Woodstock on the young rulers of Gwynedd, Owain Goch and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. This settlement lasted barely a decade before it all went up in smoke again.

The invasion of 1257 was abortive, and the royal position in Wales continued to deteriorate. Edward's ally, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, was routed in a battle at Montgomery. An army sent into West Wales on Edward's behalf was wiped out to a man at Cymerau. And so forth. It seemed nothing could stop the whirlwind advance of Llywelyn and his allies.

Edward himself was distracted and short of money. In 1261-2 his funds were spent on Gascony, where he conquered the viscountcy of Soule (a mountainous region similar to Gwynedd) and set up a chain of castles to guard the duchy from invasion. Some Anglocentric historians have accused him of acting like a playboy and wantonly blowing cash that should have been pumped into Wales. In reality the available finance was limited; it could be spent on one or the other, not both. He chose Gascony.

In 1263 Edward had to be practically dragged home by his father to deal with the permanent crisis in Wales. He led an army into Gwynedd, but gave up after two months of being dragged about in circles by Welsh guerilla fighters. Again, his lackadaisical attitude contrasts strongly with the energy displayed elsewhere.

In 1265 Edward sold off his interests in the royal boroughs of Cardigan and Carmarthen to his brother, Edmund. This was two years before the Treaty of Montgomery, in which the remainder of Edward's holdings in Wales were granted to Llywelyn.

Afterwards the prince couldn't wash his hands of Wales fast enough. He pressured his father, the king, into granting the homage of Welsh lords to Llywelyn. These included Maredudd ap Rhyd Gryg, one of the commanders of the Welsh army that had wiped out Edward's men at Cymerau, ten years earlier.

Maredudd, head of the House of Dinefwr, was the only Welsh ruler to reserve his homage to the king. A clause in the treaty allowed for that homage to be sold to the Prince of Wales for 5000 marks, if the king chose. At Edward's insistence, Henry triggered the clause and Maredudd was sold to the man he hated above all others. Llywelyn failed to stump up the cash, which was still outstanding ten years later.

I have often argued on Facebook – a great way of wasting one's time – with those who insist Edward always had a plan for the conquest of Wales. That is to read history backwards. If such a plan existed, it was an extremely convoluted one, in which Edward dragged his feet, sold off his Welsh interests and pushed the opposite of a divide-and-rule policy.

So, the reasons for the conquest don't lie in the fermenting bosoms of Nedward Badshanks. It's very very complicated, and facts don't care about anyone's feelings.

Published on December 21, 2021 06:06

December 19, 2021

Bycarr's Dyke

“Sir Edward with his army after him did follow,

And he offered him terms of peace fair enough,

As being kindred by blood, and hostage for him took.

Sir Simon believed him, and forsook his fellows.”

- (Robert of Gloucester)

In December 1265 Lord Edward laid siege to Montfortian rebels holed up in the Isle of Axholme; a marshy, waterlogged region similar to Ely in Cambridgeshire. The Montfortians were led by Simon de Montfort junior – called 'Bran' in the Sharon Penman novels – who had retreated to Kenilworth after the battle of Evesham in August. Despite the death of his father and so many of his followers, Simon chose to continue resistance:

“After gathering to himself a large company of horse and foot, he [Simon] took possession of a marshy area surrounded by large rivers, commonly called Axholme, soon after the feast of the pope Sain Martin; and, to make a safe refuge for themselves in that place, they skilfully blocked off the ways in an out, which were already exceedingly difficult, they also set guards to watch the narrow ways and the river crossings, to effectively bar any from outside entering it.”

- (Thomas Wykes)

Axholme must have been a bleak spot, especially in the winter months. Simon was joined by many of the northern Montfortians who had failed to support his father at Evesham. Their chief was Sir John de Eyvill, lord of Egmanton inside Sherwood Forest, accompanied by his younger brother Robert and their adherents.

The rebels used the island as a base for raids on the countryside. Bands of them rode out to ravage Lincolnshire, taking food and livestock and ambushing travellers on the Great North Road, the main artery that connected London to York. Among their victims was Peter Beraud, the head of a firm of Italian bankers employed by Lord Edward to fund his military campaigns. Simon and his men were not just committing random crimes: they deliberately targeted financiers to the crown, to cut off the flow of funds and hamstring the royalist war effort.

The king sent Edward and his cousin, Henry of Almaine, to deal with the nest of rebels holed up in the marshlands. En route they raised the militia of Nottingham and Derby, although not everyone was keen to serve. In January 1266 a number of local men who failed to attend the muster were amerced (fine) as punishment.

Edward forced the rebels to surrender via the use of pontoon bridges, a tactic he later employed in Wales and Scotland. First he surrounded and blockaded the island, and then had his engineers construct a system of wooden bridges in the northern part of Axholme. Possibly he was copying the tactic of his ancestor, William the Conqueror,who had built a similar causeway to destroy the 'camp of refuge' at Ely in 1071. The remains of William's causeway could still be seen in the 13th century.

The bridge opened up a crossing into the heart of the isle, which forced Simon and his men to retreat south. Hemmed in on both sides, they submitted to a truce at Bycarr's Duke, in the southern part of the isle between the rivers Idle and Trent. This must have been quite galling for Simon, who had run away from Edward at Kenilworth in 1265, clad in just his underpants. Now he had gone down a second time before cousin Ted, although on this occasion he got to keep his clothes on. Simon agreed to surrender and stand trial at Northampton in January. His followers agreed to stand trial before the king at Easter.

Simon turned up for his trial and swore an oath to leave England and do nothing to harm the kingdom while abroad. In exchange King Henry would grant him an annual pension drawn from the revenues of lands in England that had once belonged to Simon senior. The prisoner was then handed over to Edward's custody, but feared his guards would murder him. He escaped and fled to the Cinque Ports, where he hopped aboard ship and skipped over to France. Since he had broken his oath, Simon lost his right to the pension. He never saw England again and died in Italy a few years later, 'cursed by God, a wanderer and a fugitive'.

As for his men, John de Eyvill and the rest, they all cheerfully forsook their oaths and went back into revolt a few weeks after the Bycarr's Dyke agreement. This was a common theme of the period: everyone swore oaths and then broke them when the promises were no longer convenient. In that respect there isn't much point looking for moral high ground to stand on, because there was none.

Published on December 19, 2021 04:42

December 15, 2021

The white-headed one

“I would knowe...whoe the penwyn and Penhir were that betrayed Dafydd ap Gruffudd ap Llywelyn.”

“I would knowe...whoe the penwyn and Penhir were that betrayed Dafydd ap Gruffudd ap Llywelyn.”This question was posed by the Welsh copyist John Jones of Gellilyfdy in a letter to his cousin Robert Vaughan in 1649. He was referring to the capture of Prince Dafydd on the Bera mountain in 1283, and the identity of the 'traitor' who did the dirty deed.

The penwyn and Penhir translates as the 'white-headed one' and the 'long-headed one'. John Jones's source was an obscure four-line englyn, which he copied from an earlier manuscript in about 1610.

The last section of the englyn translates as:

'...lord, for sixteen pounds [and] and a stockade full of new cattle, shall sell fair Dafydd'.

The first two lines are problematic:

'Y Penwyn ar pennir arbennaic//vnben

er vnbvnt arbythmeg...'

Jones understood the first four words to refer to two individuals. As it happens, there was indeed a long tradition that a man named Penwyn had betrayed Dafydd to the English; the tale surfaces in at least three other printed works in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The search for a historical Penwyn is – for a miracle – very straightforward. There is only one candidate, a man of the late 13th century who held lands inside Gwynedd. His baptismal name was Iorwerth ap Cynwrig ap Iorwerth, but is consistently referred to as 'Y Penwyn' or 'Penwyn', possibly due to prematurely greying hair.

Penwyn married Angharad, the daughter of Heilyn ap Tudur, and was thus connected to the powerful Wyrion Eden kindred. He spent his childhood in the 1240s as a hostage in England, but was released in 1263. His father Heilyn was initially a supporter of Henry III, but then switched to the service of Prince Llywelyn and witnessed one of the latter's final land grants, at Dolwyddelan in August 1281.

Whatever his father's choices, Penwyn spent his adult life as a trusted royal servant. Between 1285-87 he was paid £114 for his service under Sir John Bonvillars, a Savoyard knight who was buried alive at the siege of Dryslwyn in 1287, when the undermined wall collapsed on top of him. Penwyn survived and continued to benefit from royal patronage. He was awarded the bailliwck of Nantconwy and remained loyal during the revolt of Prince Madog in 1294.

Penwyn died in about 1317. His sons had continued the tradition in royal service and one of them, Tudur, was killed at Bannockburn. This man is the only named Welsh casualty of that famous battle.

The surviving brothers complained to Edward III that their lands, awarded by Edward I, had been stolen by William Shaldeford and his master, Roger Mortimer. The king appears to have ignored their plea and in 1331 Shaldeford was confirmed in these lands. A few years later he was ambushed and murdered by a party of Welshmen, both for his alleged role in the deposition of Edward II, and the hatred he had incurred among the Welsh gentry.

And so on. The question is whether the unknown composer of the englyn is correct: was Penwyn the man who captured Prince Dafydd? In their petitions, his sons repeatedly pointed out that he had done good service for Edward I in Wales. Yet they did not specifically mention Dafydd, which is surprising if Penwyn had indeed snared the king's great enemy.

However the tale of Penwyn pops up in a most unexpected source. This is the Scoticronicon of Walter Bower, a 15th century Scottish annalist. As an enthusiast for the liberty of Scotland, Bower drew upon his knowledge of the Edwardian conquest of Wales as a warning to the Scots of the perils of disunity. Bower attributes the downfall of Wales to a certain 'Penvyn', who betrayed his country to King Edward. After the conquest is completed, the king betrays Penvyn in turn and executes him.

The real Penvyn/Penwyn was not executed, but lived out his life in royal service. It is interesting, however, to find Bower drawing upon a garbled memory of a real individual to spin a morality tale.

In summary: case unproven, but not closed.

(All of the above information was mined from Dylan Foster Evans' brilliant article on Open Access at Cardiff Uni: Welsh Traitors in a Scottish Chronicle: Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Penwyn and the Transmission of National Memory.)

Published on December 15, 2021 07:27

December 11, 2021

The death of Llywelyn

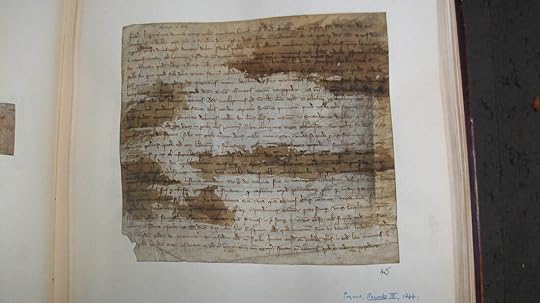

Today is the anniversary of the death of Prince Llywelyn in 1282. Attached is my photograph, from 2019, of a private letter from the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Peckham, to the Lord Chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, Robert Burnell.

Today is the anniversary of the death of Prince Llywelyn in 1282. Attached is my photograph, from 2019, of a private letter from the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Peckham, to the Lord Chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, Robert Burnell.This was dispatched sometime in the week following Llywelyn's death. I won't produce a translation as it seldom meets with any interest. Peckham wrote to Burnell shortly after he met with Edmund Mortimer at Stretton Sugwas in Herefordshire, very soon after Llywelyn was killed.

In his letter, Peckham recites Mortimer's version of events. He then warns Burnell to be on his guard, since the Marcher lords are conspiring against the king. These are the same Marchers who had conspired to kill Llywelyn. The archbishop had clearly listened to Mortimer and smelled a very large, Mortimer-shaped rat.

Peckham's warning is routinely ignored, even though this is one of the most important sources we have for the death of Llywelyn. I presume that is because it implies that Edward I was not directly involved in the conspiracy against the prince, which is just too messy and complicated. We must have the straight narrative, Goodies vs Baddies.

This is not a case - as some will inevitably accuse – of whitewashing the king. We know he was perfectly capable of such things: for instance, Edward was heavily involved in the plot to kidnap Count Floris of Holland in 1296. So what? The fact a man is capable in the one instance does not mean he did it in the other.

In any case, whatever the king chose to do is really a distraction. Of far more interest is the evidence that has recently come to light of the Welsh landholders of Builth & Brycheiniog, and their involvement in Llywelyn's demise. We know the prince met his death on or adjacent to lands held by Einion ap Madog and Owain ap Meurig, two of the Welshmen of Builth who had fought against him in the previous war. Future discussion and research has really got to focus on how this situation came about.

.

Published on December 11, 2021 08:28

Sheriffs and stewards

Something on the corruption of sheriffs in medieval England, and how the government dealt with it. I know very little about the situation in the early Norman period, but by the reigns of Henry III and Edward I the problem could no longer be avoided.

Something on the corruption of sheriffs in medieval England, and how the government dealt with it. I know very little about the situation in the early Norman period, but by the reigns of Henry III and Edward I the problem could no longer be avoided.In the first decade of Edward's reign, a serious effort was made to tackle the issue via some radical new legislation. In November 1276 the bulk of the kingdom was reorganised and divided into three blocs under a trio of stewards. Ralph Sandwich was assigned the south, the west and the west midlands. Thomas Normanville was assigned to Kent and seven counties in the north and north midlands. The 14 remaining counties in the east and east midlands went to Richard Holebrok.

These men had interesting backgrounds. Ralph Sandwich had been a prominent Montfortian during the civil wars, but was serving as a royal minister again from 1273. Normanville and Holebrok came from minor knightly families and had not held office before. Each was put on a considerable salary of £50 a year, presumably to stop them from feathering their own nests.

The point of this new system was to abolish the office of escheator in the counties, and to downgrade the role of the sheriff. Escheators were a kind of royal official who served alongside sheriffs, and even more corrupted. Doing away with them reduced the number of local officials – bound to be a popular measure – and gave the crown tighter control of the localities.

The sheriffs were now strictly supervised and accountable at the Exchequer, with very little freedom of action. Real power in England lay with the trio of stewards, who in turn reported to the king and council. Many of the sheriffs came from the upper tiers of the knighthood and baronage: in that respect it is interesting that Edward placed three relatively low-born men over them. The stewards were also made custodians of castles, and empowered to hear complaints against sheriffs and tax collectors.

This radical new policy was driven by the Hundred Rolls, a massive government enquiry into the state of the counties in England. When the results poured into Westminster, the government was faced with an endless list of complaints and petitions against the corruption of local officers. This started at the top with the sheriffs, and spread down to the bailiffs and beadles who worked for them.

Ultimately, the stewardships were no more than an experiment. The new system lasted just seven years, until it was abandoned in 1283 in favour of the old. This may have been due to the stewards being over-burdened by the sheer volume of work. They were superseded by another new arrangement, whereby complaints were heard before royal justices – 'eyre justices' – as they travelled about the kingdom:

“All these experiments emphasised the resourceful and inventive quality of Edwardian government in its approach to a perennial problem.”

- JR Maddicott, Edward I and the Lessons of Baronial Reform

Published on December 11, 2021 04:19

December 10, 2021

Power and control (3)

In early 1256 Prince Llywelyn invaded Meirionydd and drove the local lord, Llywelyn ap Maredudd, into exile. The latter was the grandson of Llywelyn Fawr, who had sworn homage for his land to Henry III in 1241. This was a form of insurance, to protect the lords of Meirionydd from the ambition of the rulers of Gwynedd.

In early 1256 Prince Llywelyn invaded Meirionydd and drove the local lord, Llywelyn ap Maredudd, into exile. The latter was the grandson of Llywelyn Fawr, who had sworn homage for his land to Henry III in 1241. This was a form of insurance, to protect the lords of Meirionydd from the ambition of the rulers of Gwynedd.Fifteen years later, Prince Llywelyn chose to retake the land by force. After conquering Lord Edward's territory in Perfeddwlad, he turned south to Meirionudd and expelled Llywelyn ap Maredudd and his family. They fled into exile in England.

Shortly afterwards Llywelyn wrote to Henry III, commending himself to the king as one who preferred fidelity to unfaithfulness and pleading for financial aid. In response Henry granted the exiles an annual pension from the royal exchequer.

Llywelyn had four sons. The eldest was Madog, who would one day revolt against Edward I and proclaim himself Prince of Wales. In 1256 that was a long way off, however, and Madog spent the first two-thirds of his life as a crown loyalist. The lords of Gwynedd created this situation, just as they incurred the enmity of the lords of Powys Wenwynwyn, Morgan ap Maredudd, Gruffudd Llwyd and the Welshmen of the Middle Marches. One might argue you cannot make an omelette without breaking eggs – which is fine, so long as the eggs don't turn round and break you.

In 1263, after seven years in exile, Llywelyn was killed in a battle at the Clun. The Annales Cambriae reports his death:

“On 25 May at Clun there were killed nearly a hundred men, among whom was Llywelyn ap Maredudd, the flower of the juveniles of all Wales. He indeed was strenuous and strong in arms, lavish in gifts and in advice prophetic and he was loved by all”.

The Clun, near the border of SW Shropshire, is a long way from Meirionydd. Further light is shed by an enquiry of 1308, which discovered that Prince Llywelyn drove Llywelyn's four sons from their patrimony shortly after their father's death. Afterwards he compensated the two eldest, Madog and Dafydd, with lands on Anglesey, but their younger brothers got nothing.

The death of Llywelyn at the Clun on 25 May coincides with the timing of Lord Edward's expedition into North Wales in spring 1263. While Edward campaigned in Gwynedd, his allies Hamo Lestrange and Roger Mortimer fought Prince Llywelyn's men in the middle Marches. They weren't very successful: Edward's French mercenaries could not bring the Welsh to battle, while Lestrange was defeated at Abermule and Mortimer was gravely wounded by an arrow in a skirmish. The latter incident occurred three days before the battle at the Clun, though the location is uncertain.

Since Llywelyn ap Maredudd had been a royal pensioner for the past seven years, and his sons were afterwards driven back into exile, the most likely scenario is that he was part of Edward's expedition. His motive was obvious, and a repeat of the strategy of his father and grandfather: exploit an English alliance to get his lands back. On this occasion it failed and he died in arms, fighting other Welshmen.

Published on December 10, 2021 05:00

December 9, 2021

Power and control (2)

Prince Llywelyn the Great's cousins, Gruffudd and Maredudd ap Cynan, fought each other for control of Meirionydd in North Wales. After Gruffudd's death in 1200, his son Hywel continued the feud and drove Maredudd into exile. Hywel then submitted to Prince Llywelyn.

Prince Llywelyn the Great's cousins, Gruffudd and Maredudd ap Cynan, fought each other for control of Meirionydd in North Wales. After Gruffudd's death in 1200, his son Hywel continued the feud and drove Maredudd into exile. Hywel then submitted to Prince Llywelyn.Hywel died in 1216, still a young man. He appears to have left no sons. Maredudd, who had died in 1212, left two sons. These were Llywelyn Fawr (the elder) and Llywelyn Fychan (the younger).

Prince Llywelyn decided the heirs of Maredudd should not be allowed to have their inheritance. Instead he installed his eldest son, Gruffudd, as ruler of Meirionydd and Ardudwy. As stated in my previous post, Gruffudd was the child of Llywelyn's first marriage to Rhunallt, daughter of the King of Man.

It has been said that Llywelyn wished to completely disinherit Gruffudd. This is an exaggeration. At first he tried to find a role for his eldest son, but it appears Gruffudd was not equal to the task. In 1221 Llywelyn was obliged to eject Gruffudd from Meirionydd as a result of the latter's harsh rule. His disgrace was only temporary: two years later he was leading his father's forces in Ystrad Tywi, and granted lands adjacent to Strata Marcella.

There remained the problem of Meirionydd. Llywelyn chose to take the lordship under his direct control, which may explain the construction of Castell y Bere between 1221-40.

Yet the two sons of Hywel remained on the loose, and in 1241 they allied with the King of England, Henry III. Thanks to an unusually dry summer, the king was able to quickly move his forces into Gwynedd and force Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn, Llywelyn the Great's successor, to restore Meirionydd to its heirs.

To ensure they would not be disinherited again, the two Llywelyns held their land of the crown instead of the lord of Gwynedd, and referred to themselves as the king's Welsh barons. For a time, then, Meirionydd was no longer under the control of the princes of Aberffraw. Llywelyn Fawr held the land until his death in 1251, after which it passed to his son, Maredudd, and then his son, Llywelyn.

Published on December 09, 2021 05:32