David Pilling's Blog, page 10

January 16, 2022

Tudurs and Tudors

In early January 1283 the royal army laid siege to Dolwyddelan in North Wales. On the 16th the keeper of the Wardrobe summoned eleven masons to start work on re-fortifying the castle as soon as it was taken.

In early January 1283 the royal army laid siege to Dolwyddelan in North Wales. On the 16th the keeper of the Wardrobe summoned eleven masons to start work on re-fortifying the castle as soon as it was taken.Two days later the castle fell. A brief note in the record of building works states:

'And let it be remembered that the king's men first entered [Dolwyddelan] castle on Monday 18th January'.

Dolwyddelan may have surrendered at once, or even by prior arrangement. A wage account that starts on 5 December notes the presence of Tudur ap Gruffudd, constable of Dolwyddelan, at the royal court for twelve days. This is likely to be a scribal error for Gruffudd ap Tudur, who served as royal constable of the castle from at least 1284.

Gruffudd and his brother Tudur were the sons of Tudur ap Madog, a long-serving minister of Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn and Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. The family had received considerable grants and privileges from the princes, including immunity from services and renders on their lands – 'gwelyau' – at Dindaethwy.

It is notable, however, that neither of Tudur's sons appeared in the service of Prince Llywelyn. Gruffudd remained constable of Dolwyddelan until 1294, when he switched sides again and briefly joined the revolt of Prince Madog ap Llywelyn.

He seems to have survived the revolt: a man of the same name appears as rhaglaw (bailiff) of Tegeingl in the Cheshire Pipe Rolls for the turn of the century. His brother Tudur was granted the vill of Penhwnllys on Anglesey in 1284, and a further royal grant of £20 in 1290, both for good service. Tudur's co-heirs were still in possession in 1352.

Published on January 16, 2022 05:03

January 14, 2022

Powerful kindreds

Between 13-19 January 1295 Edward I retraced his route from Nefyn to Conwy. Somewhere en route his baggage train was supposedly ambushed and captured by the Welsh.

Between 13-19 January 1295 Edward I retraced his route from Nefyn to Conwy. Somewhere en route his baggage train was supposedly ambushed and captured by the Welsh.This incident is reported by two English chroniclers, Trivet and Guisborough. None of the Welsh annals mention it, and the English narratives are far from clear. When JG Edwards combed the records for further information in the 1960s, he came to this thrilling conclusion:

'There is no evidence of panic at Conwy, and no special urgency in the king's commands'.

So much for that. The invaluable Book of Prests contains more information on Welshmen in the king's service over the winter months of 1294-5. For example, p154 lists seven individuals:

Cynwrig Sais received advance wages of 40 shillings at Aberconwy on 30 December.

Cynrig Ddu received 40 shillings on the same place and day.

Madog ap Gruffudd got 30 shillings on the same etc.

Tudur Fychan received 20 shillings at Aberconwy on 4 January, after an initial payment on 26 December.

Hywel ab Tuder got 20 shillings on the same terms.

Gronw ab Llywelyn got 30 shillings on 14 November, and another 20 shillings at Aberconwy.

His brother Llywelyn also got two payments of 20 shillings and 30 shillings at Aberconwy on 4 January.

These were considerable sums, when you consider the average infantryman was on 1 or 2 pence a day. Tuder Fychan and Hywel ab Tuder sound like members of the Wyrion Eden, the powerful kindred that had come to dominate politics in North Wales. They and the other listed men could be classed as 'gentry'; the men Edward I and his heirs needed to keep onside to retain control of Wales.

Published on January 14, 2022 04:13

January 13, 2022

Prophecies of Nefyn

On 13 January 1295 Edward I was at Nefyn, halfway down the northern shore of the Llyn peninsula in North Wales. He had arrived there the previous day after riding out from Conway on 6 January and advancing to Bangor.

On 13 January 1295 Edward I was at Nefyn, halfway down the northern shore of the Llyn peninsula in North Wales. He had arrived there the previous day after riding out from Conway on 6 January and advancing to Bangor. Why the king chose to push beyond Conway, straight into the heart of territory controlled by Prince Madog ap Llywelyn and his supporters, has never been satisfactorily explained. One theory is that he went to secure the loyalty of Owain Goch, eldest brother of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. After his failed revolt against Llywelyn in 1255, Owain spent 22 years in prison at Dolbadarn castle. He was a popular figure inside Gwynedd, and his lengthy confinement provoked resentment against Llywelyn. A poet, Hywel Foel ap Griffri, composed a lament calling upon the prince to release his brother:

“A warrior made captive by the lord of Eryri,

A warrior, were he free, like Rhun fab Beli,

A warrior who would not allow England to burn his borders,

A warrior of the lineage of Merfyn, magnaminous like Beli,

A warrior of hosts, warrior of splendid armour,

A warrior protecting his people, ordering an army,

A steadfast warrior ruling his forces,

A warrior of battle, he maintained his generosity,

A warrior no more lacking in valour than Elifri…”

Owain was eventually released via the terms of the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277. Afterwards this sad, lonely figure dips out of sight and there is no guarantee that he was still alive, dwelling on his lordship of Nefyn, almost twenty years later.

The Book of Prests – advance wages for the royal army – sheds a little more light. One Humphrey de Arens, a scutifer or royal shield-bearer, was given a payment of 10 shillings while in the king's company at Nefyn. This was on top of 20 shillings he had been paid in December.

William de Ferrers, 1st Baron Groby, received a much larger payment of 100 shillings. As an aside, he was the younger brother of Edward's great rival, Earl Robert de Ferrers, also brother-in-law to Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd. The king had outlasted them both: Ferrers had died of gout, aged just forty, while Dafydd was ripped to pieces on the scaffold at Shrewsbury.

Nefyn was also the scene of an Arthurian-style Round Table tourney in July 1284. Here, in the king's presence, two teams of knights led by the Earl of Ulster and the Earl of Lincoln knocked bells out of each other in the approved manner. It was also at Nefyn that Gerald of Wales claimed to have discovered a copy of the prophecies of Merlin. This remote shore on the Llyn peninsula was a happening place.

Published on January 13, 2022 04:38

January 12, 2022

Husband and wife

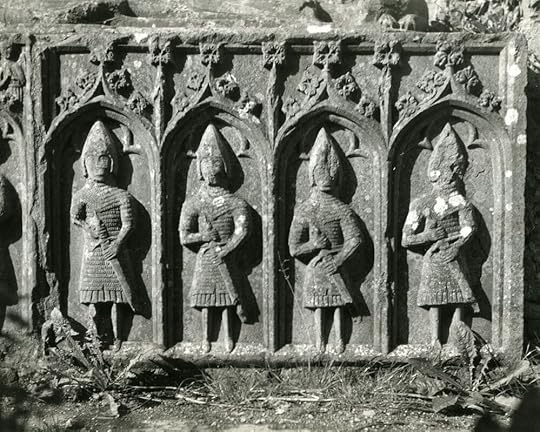

The joint tomb slab of Sir John Clanvoe and Sir William Neville. These two died in or near to Constantinople in October 1391, on a mission to offer help to the Byzantine emperor, Manuel II.

The joint tomb slab of Sir John Clanvoe and Sir William Neville. These two died in or near to Constantinople in October 1391, on a mission to offer help to the Byzantine emperor, Manuel II.The tomb slab shows their helms facing each other as though kissing, and their shields overlapping. On the shields their coats of arms are impaled – that is, each shield shows half the coats of arms of each man, a device usually reserved for the depiction of the arms of husband and wife.

Clanvoe was an extraordinary man. He was a direct descendent of Hywel ap Meurig, leader of the Welshmen of the Marches who brought down Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and prospered in the service of Edward I and his heirs.

Although the family retained interests in Wales and the March, by the late 14th century their ambition had stretched far beyond the British Isles. Clanvoe was a renowned soldier, crusader, justice and overseas diplomat, a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer and Anne of Bohemia, as well as an author and poet in his own right. In his book, The Two Ways, he practically outed himself as a Lollard, an extremely dangerous thing to do. Quote:

“Such folk as would prefer to live meekly in this world and refrain from riot, noise and strife, and live simply and eat and drink in moderation and clothe themselves modestly, and suffer patiently wrongs that others folks do and say to them...and desire no great fame or reward...such folk the world scorns and calls them 'lolleris', worthless, fools and shameful wretches...”

Clanvoe is not known to have married, and left no recorded children. It is possible that his relationship with William Neville went beyond comradeship. The Westminster chronicle records that, after Clanvoe's death, Neville refused to take food and died within two days. The manner of their burial, in the style of husband and wife, may speak volumes.

(All information taken from David Stephenson's excellent new book Patronage and Power in the Medieval Welsh March: One Family's Story).

Published on January 12, 2022 06:11

January 11, 2022

An unheard-of action...

Yesterday I posted on the Evenwood agreement in June 1300, whereby Edward I mediated a violent dispute between Bishop Antony Bek of Durham and Prior Richard Hoton. This is the follow-up.

Yesterday I posted on the Evenwood agreement in June 1300, whereby Edward I mediated a violent dispute between Bishop Antony Bek of Durham and Prior Richard Hoton. This is the follow-up.Although brokered by the king, the agreement was ineffective. Bek refused to hand back the priory estates he had taken over; the monks refused to withdraw their case against him. Both sides accused the other of bad faith.

In August the pro-Bek faction asked the bishop to name a new prior in Hoton's place. He chose Henry Luceby, prior of Holy Island. Hoton would not leave the cathedral, so Bek resorted to force.

A private war blew up. Bek summoned Philip Darcy, constable of Durham castle, who came with a force of 300 lancers of Tynedale. These men attacked the cathedral on 20 August. It was bravely defended by Hoton and forty-six monks.

When assault failed, Darcy's men lay siege. Food quickly ran out. There were no latrines inside the cathedral, so Hoton's men had to relieve themselves inside the church, 'which was an unheard of action by Christians at that time'.

Four days into the siege, Darcy smashed into the cathedral and dragged Hoton out by force from his stall. He was imprisoned in the castle and in September, threatened with violence, resigned his position. His friends helped him to stage a dramatic escape, and he prepared to put his case before the king at the Lincoln parliament of 1301.

What happened at parliament is unclear, but it seems Bek stonewalled Hoton by throwing his weight behind Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury. Winchelsey was already at loggerheads with the king, and the combined pressure of two powerful clergymen meant the Durham issue was left unresolved.

Richard Hoton was determined to have justice. He continued to press his case, and in 1304 finally brought a wide range of accusations against Bek. These ranged from a failure to return books borrowed from the library, to more important matters that affected the king. For instance, Hoton alleged that Bek's men had assaulted a royal envoy on Holy Island, smashed the seals on his letters of protection and dragged him feet first from the church. Another envoy was thrown into prison, on the grounds that none should dare to carry royal letters within the bishopric of Durham; this threatened the bishop's franchise, and implied the king was a higher power.

Bek and the king were on a collision course. The final straw came when a Scottish knight in Bek's service declared that letters from the king were valueless within Durham, as the bishop was king within his liberty, and Edward the king without.

Published on January 11, 2022 06:46

January 10, 2022

Fighting priests

In 1299 Richard Hoton, prior of the cathedral convent of Durham, triggered a conflict with Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham. Richard's concern was to maintain the independence of his house from Bek, who enjoyed near-absolute power within the bishopric of Durham

In 1299 Richard Hoton, prior of the cathedral convent of Durham, triggered a conflict with Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham. Richard's concern was to maintain the independence of his house from Bek, who enjoyed near-absolute power within the bishopric of DurhamTo defeat the bishop, Hoton needed powerful friends. To that end he granted prebends – church revenues – to the likes of Walter Langton, John Droxford, Walter Bedwin and John Sandal, all important men within the royal administration. He also played on Edward I's personal devotion to the cult of Saint Cuthbert: when the king campaigned in Scotland, a monk of Durham walked behind his horse bearing the saint's standard.

When Edward passed through Durham in January 1300 he confirmed various charters to the convent. Further charters were made out at Westminster in March. These marks of royal favour strengthened Prior Richard's position, until he was strong enough to take action against his subordinates, who had been giving him trouble.

These men complained to Bishop Bek, who decided to take direct action. When Bek and his retinue appeared at the priory, they were denied access. A furious argument ensued, which ended with Richard being excommunicated on the spot.

Bek, a classic fighting bishop, raised an army and laid siege to the priory and castle of Durham. The scandal inevitably reached the ears of the king: this was because one of the monks, Robert of Rothbury, managed to sneak through the lines and carry a letter to the Archbishop of York. The archbishop ordered Bek to cease and desist until the monks could appeal directly to the king.

Edward himself came to Durham on 18 June 1300, and made a speech outside the cathedral. He expressed his desire for a peaceful settlement, due to Bek's services on crusade and in the king's wars, and because of the important help offered to the king's cause by St Cuthbert. Edward I's religious faith was both muscular and literal, and he would have believed in the practical aid of the saint.

The king's mediation was accepted, and a difficult meeting took place at the episcopal manor of Evenwood, near Bishop Auckland. Bek was in a pugnacious mood and declared he would die rather than allow the king to interfere in his liberty. Edward, who was playing peacemaker, served food and wine with his own hands and went down on his knees before the bishop, pleading with him to compromise. Perhaps out of embarrassment, Bek agreed.

Yet the Evenwood agreement was only the start.

Published on January 10, 2022 05:11

January 9, 2022

Off owt his wyt...

In early January 1283 the men of Robert de Bruce were sent to Ireland to buy corn, wine and other supplies for the use of the royal army in North Wales. They were issued with safe-conducts for this mission, there and back again, with the usual proviso against trading with the enemy.

In early January 1283 the men of Robert de Bruce were sent to Ireland to buy corn, wine and other supplies for the use of the royal army in North Wales. They were issued with safe-conducts for this mission, there and back again, with the usual proviso against trading with the enemy.This Robert, 6th lord of Annandale and earl of Carrick, was the son of Bruce the Competitor and father of the victor of Bannockburn. He seems to be regarded as a bit of a makeweight, sandwiched as he was between two such dominant figures. The poor chap has even been described as little more than a 'glorified mercenary' for Edward I, which is harsh; any noble who performed the basic requirement of military service could be described in the same terms.

The Bruces played a vital role in the final conquest of Gwynedd. Robert's younger brother, Richard, was installed as captain of the royal garrison of Denbigh in October 1282, when the king's armies reconquered the lands and castles of Dafydd ap Gruffudd. Some weeks later Robert was dispatched to Ireland to fetch supplies. The brothers were with the king at Dolwyddelan on 26 May 1283, where they witnessed a grant of forfeit land, once belonging to a certain Owain ap Madog, to Queen Eleanor.

Robert would serve again in Wales during the revolt of Prince Madog in 1294-5. For that matter, he also served Edward in Scotland in 1296, while his father had fought alongside Longshanks during the Montfortian wars and in the Holy Land. Robert of Bannockburn fame continued the family tradition by serving Edward for four years between 1302-6, which may explain the tremendous shock of his final revolt against the king:

“And quhen to King Edward wes tauld,

How at the Bruys, that wes sa bauld,

Had brocht the Cumyn till ending,

And how he syne had maid him king,

Owt off his wyt he went weill ner”. (John Barbour)

My rough translation into modern English:

“And when King Edward was told,

How the Bruce, who was so bold,

Had brought the Comyn to an end,

And now made himself king,

He [Edward] nearly went out of his mind.”

Published on January 09, 2022 04:13

January 7, 2022

Loyalties in the west

Some interesting history of my own neck of the woods, Newcastle Emlyn or Emlyn Is Cuch, as it was.

Some interesting history of my own neck of the woods, Newcastle Emlyn or Emlyn Is Cuch, as it was. The Charter Rolls record that a certain Gwilym ap Gwrwared held land in the district in 1244 and five years later became a tenant-in-chief of the king upon receiving some of the forfeit lands of a certain Maelgwn in Ceredigion.

Gwilym's son, Einion, continued the royalist tradition and provisioned the castle of Emlyn against Rhys ap Maredudd in 1287-8 (Pipe Roll 16 Edward I, m.28).

As a reward Einion obtained a considerable grant of demesne land, and by 1303-4 the Emlyn lands were held by his sons William and Gruffydd by royal charter at a rent of 12d per year.

The bailiff of commote Emlyn in 1287 was Dafydd ap Meurig, who had previously witnessed one of Rhys ap Maredudd's charters to his wife, Ada de Hastings. This was the same Dafydd who fought for Edward I against Prince Llywelyn and captured one of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd's sons in the closing days of the war of 1282-3.

Dafydd ap Meurig's son, another Dafydd, was commended by the king for his loyal service in holding Emlyn against the followers of Prince Madog in 1294-5. He was further commended by Roger Mortimer in 1309, who warned against removing Dafydd from office as it would seriously endanger the peace.

An interesting detail is that Dafydd made his money by charging 'livery of seisin' to the heirs of free tenants. As I understand it, this meant charging a fee of five shillings to the heir before he could have his inheritance. This brought in a wage of forty shillings a year, on top of the revenues of the bailiwick.

At this point it becomes absurd to define these conflicts in Wales as an ethnic war between the English and the Welsh. As offensive or upsetting or controversial as it may seem, the hard fact is that Edward I and his heirs enjoyed the support of most of the Welsh landholding class below the rank of lord or prince. That statement is not meant to undermine anyone's political preference, or how they envisage the future of Wales - it just is. Denying it would be akin to denying the existence of one's own feet (and all the trouble that would bring).

Published on January 07, 2022 05:02

January 4, 2022

Brothers in arms (1)

'Likewise, Geoffrey de Pencoyt, of the same nation, after a feast which he had made for them in his house, on that same night, as they were sleeping in their beds, killed Maurice, king of Leinster, and Arthur, his father, men of very high nobility and authority.'

'Likewise, Geoffrey de Pencoyt, of the same nation, after a feast which he had made for them in his house, on that same night, as they were sleeping in their beds, killed Maurice, king of Leinster, and Arthur, his father, men of very high nobility and authority.'The above is part of the Remonstrance of the Irish, sent by certain Irish lords to the pope in 1317, at the time of the Bruce invasion of Ireland.

In this document, Domnhall O Neill, who had renounced his claim to the High Kingship to Edward Bruce, complained of the cruelty of the English in Ireland and listed specific atrocities. These included the assassination of 'Maurice and Arthur', former kings of Leinster.

The real story behind this double killing is complex. Domnhall was referring to Murtaugh and Art Mac Murrough: these two were brothers, not father and son, and joint rulers of the Mac Murrough kindred in Wicklow. They were also, via common descent from a King of Dublin, cousins to the Bigod earls of Norfolk.

Murtaugh and Art had given the English a deal of trouble in the Leinster war of the 1270s. After two royal expeditions were defeated in 1274 and 1276, Edward I ordered the justiciar, Robert Ufford, to pull his finger out and deal with the problem. The result was a massive double campaign, waged on both sides of the Irish Sea, in which the king led one royal army against the Prince of Wales while Ufford led another against the Mac Murrough. These expeditions not only coincided, but also deployed the exact same tactics of containment and economic blockade. Therefore they should not be taken in isolation, and it is possible that Prince Llywelyn and the Irish leaders were in contact.

The king himself was under no illusions. As a vassal of Philip the Hardy of France, he was summoned to take part in a French war against his own brother-in-law, the king of Castile. Edward begged off on the grounds of 'our wars of Ireland and Wales', implying he took one just as seriously as the other.

During the course of the war Murtaugh, the elder brother, was captured by a Norman knight, Sir Walter l'Enfant. Art took over the leadership, and put himself at the head of a general coalition. The records speak of 'the war of the McMurchys', 'the depredations of Art Mac Murrough and his accomplices', and so forth. The Mac Murrough were joined by the O'Nolans, as well as the more northerly O'Tooles and O'Byrnes.

Eventually Prince Llywelyn was starved into submission, while the Mac Murrough were driven from their mountain stronghold at Glenmalure. However, Ufford reported they had simply gone 'to another strong place', which meant another weary and expensive military expedition had to be undertaken.

At this point Roger Bigod stepped in and offered to mediate with his kinsmen. Rather than pounding away forever in Leinster, with heavy losses in money and men, the king agreed.

Published on January 04, 2022 04:14

January 3, 2022

The best men killed on that day

In 1280 the Red Earl, Richard de Burgh, came of age and took control of his vast estates in Ireland. One of those who benefited was Aodh Buidhe O Neill, who had consistently supported the pro-Burgh Mandeville faction against their rivals, FitzGerald and FitzWarin.

In 1280 the Red Earl, Richard de Burgh, came of age and took control of his vast estates in Ireland. One of those who benefited was Aodh Buidhe O Neill, who had consistently supported the pro-Burgh Mandeville faction against their rivals, FitzGerald and FitzWarin. Aodh now reaped his reward by gaining Norman assistance against his own enemy. This was Domhnall Og O Donnell, king of Tir Conaill (associated with present-day County Donegal). Domhnall was a fierce opponent of the Normans, especially the FitzGeralds, and kin to other 'resistance' figures in the north-west. These included Hugh McFelim O'Connor, credited as being the first to import Scottish galloglass warriors to Ireland.

Domhnall was also opposed to the O Neill, and in 1281 invaded Tir Eoghain with a large hosting. He found Aodh and Thomas Mandeville waiting for him at the head of a mixed force of Irish and Normans. The ensuing battle of Desertcreaght is described in harrowing terms by the Annals of Connacht:

“The battle of Desertcreaght between the Cenel Conaill and the Cenel nEogain this year. Aed Buide son of Domnall Oc son of Aed Meith son of the Aed who was called An Macam Tonlesc with the Ulster Galls was on the one side, and on the other was Domnall O Domnaill, king of Cenel Conaill and Fermanagh and Oriel, most of the Ulster Gaels, almost all Connacht and the whole of Brefne. The Cenel Conaill were routed in that battle and in it was killed Domnall O Domnaill, the best of all Irish Gaels for generosity, valour, lordship and nobility at that time and the general guardian of all Western Europe. He was buried at Derry, having triumphed in all good things down to that day. And these are the best men who were killed with him on that day:—Maelruanaid O Baigill, chieftain of the Three Tuatha; Eogan son of Maelsechlainn O Domnaill; Cellach O Baigill, the best chieftain for clemency and the best-esteemed and most bountiful in his day; Gilla Crist Mag Flannchaid, chieftain of Dartry; Domnall Mac Gilla Findein, chieftain of the Muinter Peotachain; Aindiles O Baigill and his son Dubgall; Enna O Gairmlegaig, king-chieftain of the Cenel Moain; Cormac son of An Fer Leginn (the Scholar) O Domnaill, chieftain of Fanat; Gilla an Choimded O Mailaduin, king of Lurg; Carmac son of Carmac O Domnaill; Gilla na nOc Mac Dail re Docair; Maelsechlainn son of Niall O Baigill; Aindiles son of Niall O Domnaill; Lochlainn son of Muirchertach O Domnaill; Flaithbertach Mac Buidechain; Magnus Mac Cuinn; Gilla na Naem O hEochacain; Muirchertach Mac in Ultaig; Muirchertach O Flaithbertaig and many others not enumerated here, sons of kings and chieftains and warriors.”

After this bloodbath, Thomas Mandeville collected a bounty at the Dublin exchequer for bringing in Domhnall's severed head. Aodh and other 'Irishmen of Ulster' were rewarded with fees amounting to £18, while an intriguing additional payment went to Aodh's ally, O Hanlon:

“To O Hanlon, for his expenses coming from Uriel to Dublin, to the chief justiciary of Ireland, with men-at-arms to expedite affairs of the King, and for a robe of the King's gift to him”.

The reference to men-at-arms implies O Hanlon had a troop of Norman-style armoured cavalry: this would imply that Irish rulers, or some of them, were mixing and matching Norman and Irish fighting styles.

These gifts imply that Aodh and O Hanlon were now dealing direct with Edward I's ministers in Ireland, rather than the Red Earl. This was a risky game, since de Burgh reigned supreme in Ireland and the king more or less relied on him to keep the lordship in some kind of order. Edward himself never set foot in Ireland and always governed it at several removes, except when he needed Irish money and soldiers.

Published on January 03, 2022 06:57