David Pilling's Blog, page 13

November 25, 2021

King's Welshmen

In summer 1283 a Welsh officer, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ap Grogan, was sent into Penllyn in North Wales to hunt down 'malefactors'. He was paid fourpence halfpenny a day for 13 days to complete this task. The verb used – 'insidiare' – implies he was not simply searching for men, but actively trapping or ambushing them.

In summer 1283 a Welsh officer, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ap Grogan, was sent into Penllyn in North Wales to hunt down 'malefactors'. He was paid fourpence halfpenny a day for 13 days to complete this task. The verb used – 'insidiare' – implies he was not simply searching for men, but actively trapping or ambushing them. The 'malefactors' in question were the last followers of Prince Llywelyn and Prince Dafydd, who maintained resistance in the hills and forests of Penllyn after the death or capture of the princes. Llywelyn – who ironically had the same name as the slaughtered prince – was engaged on a grim and bloody task. We know from surviving tax records for the next year, 1284, that only ten of the forty bondsmen of Penllyn were still alive. All the tenants of the commote of Penllaen, meanwhile, were dead and their lands laid waste – 'terra vasta'.

Penllyn was hit especially hard because it was the site of four of Prince Llywelyn's vaccaries or cattle farms, holding 250 cows to provide meat and milk for the prince's troops. In the usual style of medieval warfare, Edward I's troops targeted this region to destroy enemy supplies.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ap Grogan was a man of Anglesey, evidently a crown loyalist who benefited from the destruction of Prince Llywelyn and his followers. In 1300, as a reward for good service, he was granted the forfeit lands on Anglesey of Cynan ap Llywelyn, who had died fighting for the prince.

Anglesey was bitterly divided between supporters of king and prince. In 1277 another landholder on the isle, Iorwerth Foel, joined the royal army against Prince Llywelyn, who burnt Iorwerth's lands in reprisal. Iorwerth later fought as a mounted officer at the battle of Falkirk. Another landholder on the isle, Tudur ap Gruffudd, fought for the king against Prince Llywelyn and Madog ap Llywelyn, as well as doing military service in Ireland. Tudur was also in receipt of 20 shillings per annum for five years for his work on the new castles in North Wales, called the 'Iron Ring'.

All this presents a very complicated picture, and shows deep fractures and fault-lines in the principality at a crucial time. Why so many Welshmen chose to fight for the King of England against the Prince of Wales is an endless source of discussion – or should be, looking forward, because it is undeniable. One could also point at Dafydd Fychan of Newcastle Emlyn, who captured one of Prince Dafydd's sons on the Bera mountain, or Bleddyn Fychan, who served as the Earl of Lincoln's land agent in the aftermath of conquest. Then there were the great gentry figures such as Morgan ap Maredudd, Gruffudd Llwyd, Gruffudd Fychan de la Pole and Madog ap Llywelyn of Bromfield. Etcetera.

It isn't a simple question of patriotism; there were all kinds of issues of lordship, homage, patronage and other contemporary concerns at stake.

(Thanks to David Stephenson for correcting my translation of the original Latin)

Published on November 25, 2021 06:30

Contra pacem

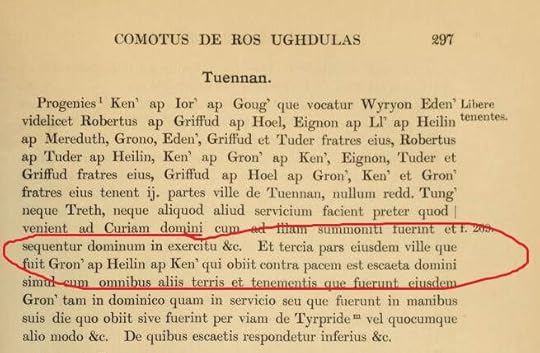

The Survey of the Honour of Denbigh, a record of the lordship of Denbigh in North Wales drawn up in 1334, contains a brief but poignant entry:

The Survey of the Honour of Denbigh, a record of the lordship of Denbigh in North Wales drawn up in 1334, contains a brief but poignant entry:“Gron' ap Heilyn ap Ken' qui obiit contra pacem...”

This records that Goronwy ap Heilyn had died 'contra pacem' or against the peace. He was killed in the last months of the Palm Sunday revolt of 1282-3, which ended in the conquest of Wales.

Goronwy was a member of the Wyrion Eden, an important kin-group in North Wales descended from Ednyfed Fychan, distain to Llywelyn the Great. He served Llywelyn's grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, as a leading figure of the ministerial elite set up by the rulers of Gwynedd to organise government and establish better relations with the English crown. Goronwy was also a skilled lawyer and diplomat, just as comfortable and at-ease inside the corridors of Westminster as as he was within the halls of Aberconwy.

There is little in Goronwy's long and distinguished career to suggest he would end up dying on English blades. In his youth he was held hostage in England by Henry III, but later returned to Wales and found a place in the household of Prince Llywelyn. In 1277 he and his kinsman, Tudur ab Ednyfed, were granted powers by the prince to conclude peace with Edward I. Along with another kinsman, Dafydd ab Einion, Goronwy also arranged for the transfer of hostages for the observance of the Treaty of Aberconwy.

Goronwy was serving two masters. Between 1277-81 he made four journeys to Snowdonia and Anglesey on the king's service, and claimed expenses for his journeys to Wales to negotiate with Llywelyn about his dispute with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. In 1278 he was entrusted by Llywelyn to talk privately with Eleanor de Montfort, held in custody at Windsor castle.

In the same year Goronwy was awarded a fee of £6 a year by King Edward, served as a royal bailiff of Rhos in North Wales, and was appointed to the Hopton Commission, a royal survey into Welsh laws and customs.

Up until this point, Goronwy was acting as a point of contact between the rulers of England and Wales, and had the trust of both. Otherwise Edward would not have permitted him access to Eleanor de Montfort, a high-status prisoner in tight custody, or appointed Goronwy to important judicial posts. Equally, Llywelyn would not have allowed Goronwy to handle so many delicate negotiations.

This all changed in 1282, when Goronwy was among those who submitted a long list of grievances against English rule to Archbishop Peckham. Goronwy's specific complaints were aimed at Reynold Grey, the recently appointed Justice of Chester and lands east of the River Conwy. He complained that Grey had removed Goronwy from his post as bailiff, and sent a band of soldiers to murder him; he had barely escaped with his life. The cause of this private feud is unclear, but it seems Grey was happy to use violent, heavy-handed methods: the people of Rhos and Rhufoniog complained that he threatened to behead any man who went telling tales to the king.

For the last few months of his life, Goronwy was a firm partisan of Prince Llywelyn and, after Llywelyn's death, Prince Dafydd. He last appears among the witnesses to Dafydd's futile charters, issued in May 1283, summoning men to arms to defend the heartlands of Gwynedd. The plea fell on deaf ears, and Dafydd and his last supporters fled in all directions. Goronwy was killed shortly afterwards, probably in the man-hunt that spread all over Wales. Many of his kin, however, would find places for themselves in the postconquest regime.

Published on November 25, 2021 02:23

November 24, 2021

Kissing cousins

A research snippet from my upcoming book on Edward I and France (date of publication TBA).

A research snippet from my upcoming book on Edward I and France (date of publication TBA).In about 1280 Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, wrote to the king. This is part of the secret correspondence between the officers of the duchy and the crown. Jean describes that a young man named Ebles, son of the Viscount of Ventadour, has married a woman named Galienne. This was done with the approval of Galienne's friends, but against the wishes of the suitor's uncles, the Bishop of Limoges and the Count of Périgord.

To scupper the marriage, these two tried to disinherit their nephew by pleading to the King of France, Philip; they warned the king that this marriage, if allowed to go ahead, would 'turn to black favours and their confusion'.

In response Philip took the girl, Galienne, under his 'protection'. She didn't want to be protected, or stopped from marrying Ebles, but her wishes didn't count. Philip used the incident as an excuse to intervene in the duchy's affairs and undermine the power of the English king-duke. This was the consistent policy of the Capetian kings of France after the Treaty of Paris in 1259, whereby the Plantagenets became their vassals for the duchy.

The seneschal, Jean, begged Edward to contact Philip and request him not to disturb the marriage of a faithful vassal. There seems to be no record of Edward's response, but the point is that he and his successors were caught between a rock and a hard place; on the one hand, they were now at the beck and call of their new overlords; on the other, their own subjects in Gascony could appeal over their heads to Paris, if they chose.

The situation would have been awkward enough, if the Plantagenets were mere 'grand seigneurs' of France. But they were also kings in their own right, and it was unsustainable for one crowned head to be the inferior of another: especially when the relationship was so dysfunctional.

Contemporaries were extremely aware of the problem. In 1306 Edward's own lawyers urged him to reverse out of the Treaty of Paris by any means possible, saving his honour; the implication being that if he could do it without saving his honour, that would be good too. At last, in 1330, the council of the young Edward III told the king to abandon completely the broken policy of his forebears, and go on the offensive.

Thus the root cause of the Hundred Years War had nothing to do with national or ethnic rivalries, even if that is how it was (very cynically) advertised: it was, essentially, a joust for sovereignty between kissing cousins.

Published on November 24, 2021 06:24

November 23, 2021

God, not man

Something I just received from the National Archives. This is part of a memorandum for the arrangements of a joint crusade between England and France, dated May-June 1286, when Edward I did homage for his French lands to Philip IV.

Something I just received from the National Archives. This is part of a memorandum for the arrangements of a joint crusade between England and France, dated May-June 1286, when Edward I did homage for his French lands to Philip IV.This particular membrane outlines the terms via which Gaston de Moncada, Viscount of Béarn, would serve both kings in the Holy Land. For the debts he owed to Edward, his castles would be destroyed except for those the king-duke took into custody. Gaston had no choice in the matter: he was required to go on crusade, never to return except recalled by Edward.

The agreement – essentially a forced indenture – marks the point that Gaston finally overstepped the mark. After a long and turbulent career spanning forty years, he arranged for his daughter Margaret, countess of Foix, to inherit the county of Béarn. This would fuse the provinces together, creating a single power bloc in southern Aquitaine that threatened the hegemony of his overlords, Edward and Philip.

Whatever their private quarrels, the two kings weren't about to be undone by this little squirt. They were first cousins once removed, senior partners of the Francophone mafia that ruled most of Western Europe. Gaston was a very junior partner in the family firm, and made an offer he could (quite literally) not refuse.

The 'offer' is almost identical to that Edward made to Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd of Wales, at the height of the Palm Sunday revolt in 1282. As such it can be seen as a consistent policy. The kings of France and England were honour-bound to send what military and financial aid they could to the Latin states in the east. With his usual pragmatism, Edward hit upon a scheme of fulfilling this duty on the cheap. Unwanted political rebels would be packed off on crusade, where they served at their own expense and – with any luck – died gloriously for the sake of Christ.

Or, if God willed, they might carve out little Christian states of their own in the desert. The point is, they would be doing it over ten thousand miles away.

In the event, Gaston agreed to go, but died before he could set out. Four knights of Béarn were sent in his stead. Dafydd refused, saying he would only travel to the Holy Land for the sake of God, not man.

Published on November 23, 2021 08:13

November 22, 2021

Praise-spreading Owain

Owain de la Pole (c.1257-93), lord of southern Powys, was one of the handful of Welsh princes to survive the conquest of Wales. The fate of the princes contrasts starkly with the Welsh gentry, many of whom prospered in the aftermath.

Owain de la Pole (c.1257-93), lord of southern Powys, was one of the handful of Welsh princes to survive the conquest of Wales. The fate of the princes contrasts starkly with the Welsh gentry, many of whom prospered in the aftermath. His political career was defined by ancestry and heritage. Owain's distant ancestors, King Madog ap Maredudd of Powys and Prince Llywelyn, were assassinated by the rulers of Gwynedd. His grandfather, Gwenwynwyn, had been driven from his lands by Llywelyn the Great. In 1218, via the treaty of Worcester, Llywelyn agreed to provide for Gwenwynwyn's heirs until they came of age and maintain the dower of his widow. Llywelyn fulfilled none of these terms, which meant that Gwenwynwyn's family was thrown onto the mercy of Henry III, who provided for them in England.

As a result, Owain was born in England, probably on the manor of Ashford in Derbyshire, which the king had granted to his father. He would have been raised in the bitterness of exile, and conditioned to regard the princes of Gwynedd as his ancestral enemies. His father, Gruffudd, spent the next forty years striving to recover his lost patrimony by any means. To that end he fought for and against pretty much everyone: the king, the rulers of Gwynedd, other Welsh princes, the lords of the March. Finally he made an awkward alliance with Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, grandson of Llywelyn the Great.

Perhaps inevitably, it didn't last. In spring 1274 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd started work on a new castle at Dolforwyn above the Severn in Cedewain, just six miles from Gruffudd's castle at Pool. This poisoned the already fragile relations between the rival dynasties, and in 1274 Gruffudd's son Owain entered into a conspiracy with Llywelyn's brother, Dafydd.

Much of the detail we have for this plot comes from Owain's own confession, made to the bishop of Bangor two years later. The plan was for Owain to gather some men and travel in secret to Llywelyn's court on a certain night in February 1274. Dafydd would be with his brother, whose household guard were absent on their customary 'cylch' or circuit of the prince's lands which traditionally took place after Christmas. Dafydd would open a gate to admit Owain and his men and guide them to Llywelyn's bedchamber, where they would murder the prince. Afterwards Dafydd would be proclaimed Prince of Wales, and Owain granted the lands of Cedewain and Ceri. Cedewain, significantly, was the area in which the new castle of Dolforwyn was located. He would also marry one of Dafydd's daughters.

The plot was foiled by a snowstorm. Civil war broke out in North Wales, and Dafydd fled into England, accompanied by his retinue or 'teulu' of 200 cavalry. Owain was seized as hostage, and held in custody when his father Gruffudd also fled into England after a murky trial at Dolforwyn.

In November 1277, via the Treaty of Aberconwy and Llywelyn's humiliating submission to Edward I, Owain was set free. He was made custodian of Dolforwyn by Roger Mortimer, which must have given him a certain satisfaction. He was succeeded as custodian by his son, Llywelyn. In the war of 1282-3 Owain and his father fought for King Edward; over 1300 Powysian footsoldiers were sent to take part at the siege of Castell y Bere.

Owain succeeded as lord of Powys in 1286. In the same year he went to France and served as a royal scutifer or shield-bearer, employed to ride behind the king and carry his banner and shield. The next year, 1287, he led a thousand archers to the siege of Dryslwyn, to help suppress the revolt of Rhys ap Maredudd.

Despite being a crown loyalist for the whole of his career, Owain was praised as 'the dread of the valley floor of London' by his court poet, Bleddyn Fardd. Possibly this was a reference to his ancestors, some of whom had fought the English, but the poem is specifically addressed to Owain. The poet also makes no reference to Owain's feud with Gwynedd, or service for Edward I.

Below is a full English translation of the poem, courtesy of Dr Adrian Price. Note the reference to the battle of Camlann, where Arthur is supposed to have met his Waterloo:

“Praise-spreading Owain, praise-spreading

Defender of fiercely-attacked Dyliffain.

No wound will come to him, no terror will befall him,

A swift, bold upholder, whose gift is gold,

The wealth of Camlan, leader of the lineage of princes,

Like Clydno Eidyn, the chief accomplice of luxury.

A steadfast sword which shatters blades, the dread of the valley floor of London,

A hero lord greatly praised in poetry, the guarantor of Britain.

The leader of the fervent army of the brave men of the east,

Leading a gold-saddled, ready steed.

An emblem which will not be called a fawn’s possession,

Privileged stag of perfect, refined praise.

The strength of a brave, mighty and generous man, defending armies,

You honour him who does not submit at matins.

While seeking provision, gold-bladed monarchs,

Gilt-sworded companion, garnering gore.

The undoubted son of Gruffudd, a fine lord,

I remember that a fine eulogy is not unrecompensed.

The grandson of unyielding Gwenwynwyn who made stiff corpses,

Wolves are his cooks around his lance.

He is Nudd of the unstinted gift, annihilating warriors,

Powerful, skilful king.

His the best laws, exalted nation,

Since when news came of Cichwain’s tribe,

Respected warrior, owner of a graceful stallion,

Proud splendour, swift hawk of corpses.

Authority of the council assembly in the fine man with outstanding gifts,

The privilege of generous wealth, wandering minstrelsy.

Red-speared lord of an exalted encounter,

Stiff, haemorrhaging Bernicians, the gracious portion of ravens,

His brave aftermath is estimated, war-reading sword,

No wonder there is wealth as far as Rome.

The fervent host of a soaring leader,

A steadfast lord, certain to defend Mechain.

A dire warning for people who may become an abundant feast for a flock of seagulls,

As one would go to battle at Rhyd Angain.

May the Lord God rise again;

The great lover of earthen-hued Darowen.

Easy for us to present, the host of Main, - his quality,

The praise-spreading defender of the gate.”

Published on November 22, 2021 04:36

November 21, 2021

A grand flop (or not)

Here is a translation of a document that Kathy Love has very kindly translated for me in the past few months, from the original old French. It is a deed of surrender from 1301, whereby the barons of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgunday agreed terms of submission with Philip IV, king of France.

Here is a translation of a document that Kathy Love has very kindly translated for me in the past few months, from the original old French. It is a deed of surrender from 1301, whereby the barons of Franche-Comté in eastern Burgunday agreed terms of submission with Philip IV, king of France.These barons had been at war with Philip for over a decade. The context was Philip's desire to bring the Franche-Comté, as well as Flanders and Aquitaine, under the direct rule of France. Franche-Comté was part of the Holy Roman Empire, but the Count of Burgundy agreed to sell his inheritance to Philip in exchange for a pension. His barons, led by Jean de Arlay, refused to submit and created a separatist league to resist the French.

In 1294 the league joined Edward I's grand alliance against Philip, in exchange for large English subsidies. As the surrender describes, they fought 'energetically' against the French, and prolonged their resistance for several years. In March 1298, in exchange for a further English subsidy, they agreed to continue 'lively and open war'. Their resistance finally ended in 1301, by which time England and France were at peace.

All of this turns Anglocentric historiography of the subject on its head. Various academics have stated flatly that 'none' of Edward's allies fulfilled their contracts, and that the grand alliance was a 'grand flop'. That interpretation is simply wrong, and betrays a certain laziness and unwillingness to access difficult sources. It doesn't matter how many letters you have after their name: if you're wrong, you're wrong.

The treaty is very long, but I have pasted it in full to give an idea of the detail and complexity of such agreements. The helpful footnotes are supplied by Kathy:

[270] Letters by which John II of Faucogney undertook, together with the other lords of the France-Comté, formerly allied against Philippe le Bel, to make good the losses caused by them to the partisans of the king of France during the war that they had fought in the county of Burgundy, and specially to have rebuilt the chateaux of Ornans, Clairvaux and la Salle (the state-owned palace)1 of Pontarlier, which were destroyed during the aforesaid hostilities. (31 May 1301)

To all those who will see and hear these present letters, We Symon de Monbéliart, lord of Montron, Jehanz of Vianne, lord of Mireber, Pierres, lord of Marnay, Estenes d’Oyseler, lord of the Vilenove, Girars d’Arguel, knights2, and Estevenat, lord of Oiseler, and Guillame d’Argueil, esquire, greetings in our Lord3, we make known that with the noble barons Jehanz de Chalom, lord of Arlay, Renaut, count4 of Monbéliart, Jehanz de Bourt, Jehanz and Gautier de Monfalcom, Jehanz, lord of Faucoigney, Thiébault, lord of Neufchestel, Humbert, lord of Clerevaux, Guachier de Chastelvilein, Huedes, lord of Monferrant, Guillames, lord of Corcondray, Jehanz d’Oiseler, lord of Flaigé, knights and

[271] Johanz de Jou, esquire, are bound [or have undertaken] by their letters sealed with their seals, toward the very high and very excellent prince our dear lord Philippe, by the grace of God king of France, to hold, keep and accomplish the promises [or covenants] contained in the said letter relating to5 the aforementioned war [which] we energetically pursued6 and made in the county of Burgundy7 contrary to the will of the very excellent prince our dear lord the king as above, we who always [‘on all days’] desire to have and to keep the grace [or favour] and the good will of our aforesaid lord the king, are at his will and his good favour [‘good accord’] and at his mercy and he has received us and has ordained and declared his will in the following manner: It is to be known that we are bound to keep, hold and accomplish all the promises [covenants] contained in the letters sealed with the seals of the noble barons above, having promised and promising before our lord the king to enter, we and our heirs, into his faith and his homage, as the king of France and to his successor kings of France, to take up again and resume toward him as sons8 the things which follow. It is to be known we, Symon de Monbéliart, lord of Montrom, forty livrées de terre9 from our borderlands10 near Rovre; We, Johanz de Vianne, in the manner stated above, thirty livrées de terre, situated at Fronthenay; We, Pierres, lord of Marnay, three hundred pounds in coin11; We, Estenes d’Oiseler, lord of the Vile Nove, thirty livrées de terre, lying at Charmoille, and a little way d’iellue12; We, Girar d’Arguel, two hundred pounds in coin; I, Estevenant, lord of Piseler, two hundred pounds in coin; I, Guillaume d’Arguel, two hundred pounds in coin. It is to be known that all these things stated above, we ought to undertake in faith and homage for us and for our heirs of our dear lord the king of France stated above, and his successors, kings of France, before the next feast of All Saints. As part of our return to fealty13 we render and have rendered, we reestablish and have reestablished, together all the barons named above, all the

[272] inheritance that we have taken in the country of Burgundy stated above, since the time that it came into the hand of our aforesaid lord the king. As part of our return to fealty we together all the other barons aforesaid will have repaired, at our own cost and expense, the chateaux [or castles] of Ornenes, and of Clerevaux, and the palisade14 of Pontarlie, and we will remake them into a sufficient state, in the judgment15 au dit et à l’esgart of the noble men our well-beloved my lord Guachier, lord of Chastillon and constable of Chapaigne, my lord Pierre, lord of Chambry, and my lord Pierre, lord of Veinnes, his son, knights, and chamberlain [or steward] [of] our dear lord aforesaid the king; as part of our return to fealty we will restore and repair all the damage and losses which we and our followers [‘aides’] have caused in the said county of Burgundy, from [the time of] the truce up to the day on which these letters are made, whether by imprisonment, in lands16, or in chattels [movable goods], or by fire, or in any other way whatsoever. And we have prayed and pray on the holy gospels that we will do and accomplish all the things aforesaid well and loyally. And every one of them. And when the aforesaid things have been done and accomplished, we together with all the other barons in manner which is contained in their letters sealed with their seals, have pledged and pledge one for the other17 [I think this means a joint and several undertaking] and we bind ourselves and our goods and our heirs, and have given pledges dou roialme18 sufficient for all the things set out above, to loyally hold, keep and accomplish, in the manner which follows. It is to be known, We, Symond de Monbéliart, have given as surety [or guarantor] Jehanz lord of Cusel, holding land in the kingdom, being the castle of Bart upon [or over] Soigney; We, Jehanz de Vianne my lord Gauthier of Monfalcom; We, Pierres, lord of Marnay, the said Jehanz lord of Cusel; We, Estèes d’Pyseler, lord of Villenove, Girars lord of Chauviré; We, Girar d’Arguel the noble baron my lord Jehanz of Chalom, lord of Arlay; Ik, Estevenat, lord of Oiseler, my lord Jehanz of Oiseler, my uncle; I, Guillame d’Arguel, my lord Vathier de Monfalcon. And so

[271] these things will be forever firm and established, We have put our own seals on these present letters. Given and made at Besancon, the Wednesday after the octave of Pentecost in the year of our Lord 1301.

1 ‘State-owned’ is the translation of domanial, but in this period it may have meant something slightly different. Perhaps this palace was the personal property of the king.

2 The abbreviation ‘chrs’ appears repeatedly. I think this must stand for ‘chevaliers’, knights.

3 I think the lord here referred to is God, and this is a conventional greeting; but it could possibly refer to the king. If it’s important, check.

4 I can’t find any translation for ‘cuens’ but I think it means ‘count’. Monbéliart became a county in the 11th century and its rulers were termed ‘count’ (or countess).

5 I think this probably means ‘relating to’ the war, but I am not sure. ‘Achosom’ looks to me like a variation on ‘achiasun’ which has a wide variety of meanings relating to cause, opportunity and reason. See https://www.anglo-norman.net/entry/achoison But again, if it’s important, get it checked.

6 The word ‘ahue’ means to urge on with shouts---probably related to ‘hue and cry’.

7 The words ‘contée de Bourg.’ appear repeatedly; I am fairly sure they refer to the county of Burgundy.

8 The words ‘rechiez à reprandre de luy en fiez’ seem literally to mean ‘return to an earlier state, and take up again from him as sons [or kinsmen]’ so I think this is a formula of restoring the feudal payments that follow.

9 Clearly a ‘livrée’ is a measure of land, but I have been unable to find any indication of how much land it was. The literal meaning is ‘delivered’ but since there are quantities attached (thirty livrées de terre) it must have a concrete meaning.

10 The words ‘de nre aluef’ could mean either ‘from our free tenancy’ or ‘from our lands near the border’. I think this case the latter makes more sense.

11 Literally ‘in pennies’ (deniers). Clearly refers to a payment in specie.

12 I can’t find any translation for this. It might be ‘d’il lieu’, meaning ‘a little distance from this place’.

13 ‘Rechief’ means to return to an earlier state, here one of feudal loyalty, so ‘de rechief’ must I think mean that the action is done as part of the return to the former state of fealty.

14 ‘Seule’ means ‘stake’ but in this context it sounds like some kind of fortification---I guess at ‘palisade’.

15 ‘A dit et a l’esgard’ literally means ‘according to the word and judgment’ so I think it is a saying that means the named men will determine whether the work has been carried out sufficiently and correctly.

16 Here ‘héritages’ means seizure of estates, I think.

17 ‘Li uns l’autre’ could mean either ‘one and all’ i.e. they all pledge, or ‘the one for the other’, i.e. a joint and several undertaking. I think it’s the former, but if it’s important, check.

18 ‘Roialme’ can mean ‘territory under the authority of a monarch’ so it may mean pledges of land within the kingdom of France.

Published on November 21, 2021 06:19

November 20, 2021

A crisis in Savoy

More thoughts on Edward I and Scotland.

More thoughts on Edward I and Scotland.One of the questions raised on this thorny subject is why the Scots invited Edward over the threshold in the first place? After all, they had seen what he was capable of in Wales. As one very bearded Scottish academic – whose name escapes me – said on a TV doc:

“He had, of course, absolutely hammered the Welsh. So what were the Scots thinking?”

This is a false comparison, in my view. The Scots had assisted in Edward's conquest of Wales, and were unlikely to have viewed themselves in the same light. Scotland had been a united kingdom (more or less) for centuries. There had been no kingdom of Wales since the 11th century, and the principality lasted barely ten years from 1267-77. Even that brief arrangement was torn up: via the Treaty of Aberconwy, Prince Llywelyn was left with his title, but no effective authority outside Snowdonia and Anglesey. The rest of the country was held of the crown, Marcher lords and descendents of the Welsh princes.

The real comparison lies on the continent. For twenty years Edward was the go-to statesman in Christendom: however negatively one might view this particular Plantagenet, there is no point denying this aspect of his career. A succession of popes begged him to intervene in wars between France, Aragon, Sicily, the Holy Roman Empire and Savoy, and he was able to negotiate the release from custody of Charles of Salerno and Enrique of Castile.

The Scots also had a precedent to draw from. In 1285 Count Philip of Savoy's heir, his eldest nephew Thomas, was killed in a skirmish. The two younger nephews then began to fight over the inheritance. Before he died, Philip charged his niece Queen Eleanor of Provence and her son Edward I with the duty of apportioning the Savoy inheritance among his successors.

This was done, with none of the devious tactics Edward deployed in Scotland. One of the surviving nephews, Amadeus, was awarded the county and title of Savoy, and the other, Lewis, got the barony of Vaud north of Lake Geneva.

There were, of course, differences between Savoy and Scotland. In 1246 a previous count had sold the lordship of Savoy to Henry III, in exchange for a lump sum and an annual pension. Edward inherited this right, and took the homage of Count Philip on his way home from Italy in July 1273. Thus, there was no issue of overlordship.

From a Savoyard point of view, this arrangement gained English protection against the encroachments of France and the empire. In 1282, Count Philip sent an urgent request to Edward, begging the king 'as your man' for help against the emperor, Rudolph, who was preparing to attack Savoy. In response Edward sent Othon Grandson, himself a Savoyard, and the Dean of Lichfield to broker peace.

So – and this is just a theory – if the Scots in 1290 had looked at Edward's career as an arbiter to date, they would have seen little to alarm them. What they didn't realise if that none of his previous dealings had involved questions of overlordship, or the prospect of gaining new territory.

Published on November 20, 2021 04:13

November 17, 2021

Great causes

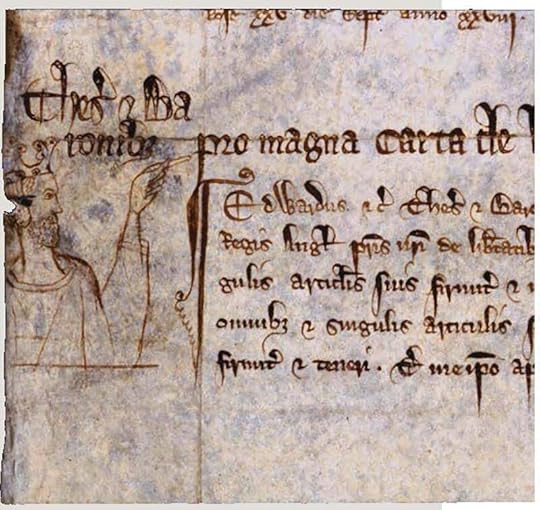

On this day in 1292 Edward I announced his final judgement on the so-called Great Cause in Scotland, whereby John Balliol became King of Scots.

On this day in 1292 Edward I announced his final judgement on the so-called Great Cause in Scotland, whereby John Balliol became King of Scots.Despite a host of claimants, the only two realistic candidates were John Balliol and Robert Bruce, grandfather of the victor of Bannockburn. Bruce went to incredible lengths to secure the crown: this included supplying the Count of Holland with forged documents and arguing that Scotland should be divided between himself, Balliol and John Hastings.

Bruce's utter lack of scruples is revealed in a letter he sent to Edward I in 1291. The original text is sadly defective, but much of it was deciphered by the late A.A.M. Duncan. Written in Anglo-Norman, Bruce states:

"I heard from my father and old folk about the time of King David" that in a war between the kings of England and Scotland, Northumberland was lost. In the subsequent peace it was provided that if the defeated Scottish king gave England any further trouble, the seven earls of Scotland were obliged to support the English king and his crown.

The next section of the letter is illegible, but then it goes on to state that Richard the Lionheart sold the homage of the King of Scotland. This meant the English no longer had any claim to overlordship over the Scots. However, Bruce kicked aside this inconvenient detail:

"...we think this sale must be invalid, for the English king and his counsil are so wise that they will soon advise themselves whethert one can dismember the crown of such a limb, and then that one must keep the crown whole."

Bruce concludes that if and when King Edward "wishes to make his demand, I will obey him and will help him by myself and by all my friends, and by my lineage whatever my friends want to do. And I beg you for grace for my right and for my truth which I wish to show before you and I earnestly intend to speak with the old folk of the land to seek out the truth of your affairs...as you have requested".

Strangely - or not - this rather crawly letter is not often mentioned in populist accounts of the Scottish wars. There is no doubt whatever that the Bruces wanted to seize the Scottish crown, and would do pretty much anything to that end. There was zero element of 'patriotism', as we understand the term, except when it served their purpose. Bruce made it perfectly clear that he was King Edward's willing doormat, and was prepared to overlook the history of Anglo-Scottish relations.

Provided, of course, Edward did his bit in return and planted a Bruce on the throne. If he had done so, the Bruces would have no qualms about accepting Edward's overlordship, at least in the short term. Instead he favoured John Balliol, and to this extent had right on his side; Balliol's claim was superior, and unlike Bruce he did not stoop to forgery or conspiring with foreign nobles.

Afterwards, however, Edward went out of his way to undermine Balliol's kingship and aggressively assert his overlordship in a way the Scots found unbearable. One theory is that Edward was deliberately trying to provoke a war, which in context seems unlikely: the English king had massive obligations to his allies on the continent, and the last thing he wanted was to trigger a conflict with the Scots while grappling with the might of France.

The mistake, in my opinion, is to look at Edward's Scottish policy in isolation. Every single feudal overlord in this era treated their vassals in the same oppressive, high-handed manner; it was simply the style of the age. Philip IV of France oppressed his vassals, as did Prince Llywelyn of Wales, King Adolf of Germany, the kings of Navarre and Castile and Aragon, even the Pope.

The weird thing is that these oppressive policies almost always provoked revolts, yet all of these rulers were remarkably slow to learn. Some of them were too slow: Adolf of Germany, for instance, ended up with his head spiked on a German lance.

Published on November 17, 2021 03:23

November 16, 2021

Church matters (1)

Two of the main players in 13th century Wales were the bishops of Asaph and Bangor. Unfortunately they were both named Anian, so to avoid confusion I'll just call them Asaph and Bangor (as opposed to Bill and Ted, or Pinky and the Brain).

Two of the main players in 13th century Wales were the bishops of Asaph and Bangor. Unfortunately they were both named Anian, so to avoid confusion I'll just call them Asaph and Bangor (as opposed to Bill and Ted, or Pinky and the Brain).Unfortunately, poor old Llywelyn ap Gruffudd could not rely on support from the Welsh church, any more than the Welsh gentry. His big problem, always, was the financial burden of the Treaty of Montgomery. It may be that Henry III consciously imposed a crippling mortgage on the principality, knowing full well that Llywelyn would never be able to pay it off. Deliberate or otherwise, that was the result. The clergy and the laity of Wales were not, to judge from their actions, inclined to appreciate Llywelyn's predicament.

His problems with the church started very soon after the Montgomery agreement. Bishop Asaph was consecrated on 21 October 1268, when Llywelyn still had control over the Perfeddwlad, east of the Conwy, where St Asaph stands. Therefore it would seem the bishop owed his preferment to Llywelyn's patronage.

Their relationship soon turned sour. The first serious breach occurred in the spring of 1269: on 1 May, at Mold, Llywelyn ordered his bailiffs to observe all the customs due to the bishop of St Asaph. This implies that such things were not being observed. As he did in other cases, Llywelyn ordered the dispute to be resolved via the English jury system instead of the law of Hywel Dda. The specific phrase used was:

“per XII probos et fide dignos hominos...”

(“twelve good and trustworthy men...”)

This is yet more proof of the sidelining of Welsh law in this period, in exchange for the English law of inquest. It was done for reasons of utility, but the rulers of Wales were effectively undermining their own legal system in favour of another. When Llywelyn complained to Archbishop Peckham that the Welsh had a right to their own laws and customs, it was a case of 'physician, heal thyself'.

Perhaps, in this case, Llywelyn used English common law to heal a potentially damaging dispute. His relations with Asaph improved for a time, and in 1272 the bishop was sent as an envoy to Henry III. Then the church versus state argument – shades of Henry II and Thomas Becket - flared up again. Two years later, the clergy of Wales wrote to the pope, stating that Asaph had falsely accused Llywelyn of attacking Welsh monks and monasteries.

The relationship continued to deteriorate. Later that year, August 1274, Asaph ordered Llywelyn to stop persecuting his brother, Prince Dafydd. This was just months after Dafydd's failed attempt to have the prince assassinated. In October a verbal war broke out when Asaph called an assembly of Welsh clergy and denounced Llywelyn's infringements of the rights of the church.

Llywelyn's response was to write to the Archbishop of Canterbury as 'his devoted Prince Llywelyn of Wales and lord of Snowdon'. The prince stated he had not wronged Asaph, and was ready to accept terms to heal the breach, but only if all parties were willing to abide by them. This time there was no mention of a jury, so it appears Llywelyn had abandoned English common law and reverted to Hywel Dda to resolve the issue. At the same time he gave money to the abbot of Valle Crucis, so the latter could travel to Rome and denounce Asaph.

To break the deadlock, Asaph turned to the king. The bishop was a clever politician, and knew that Llywelyn was out of favour with Edward I, due to his refusal to perform homage and fealty. In September 1275, shortly after Llywelyn had failed to meet the king at Chester, Asaph sent a letter to Westminster. He claimed the prince had imposed an illegal tax on Wales, on the false pretence that he had made peace with Edward and needed a tax of 3d (pence) on each head of cattle to pay the outstanding mortgage:

“Where some people are astonished and afraid, and suggest to me that I should report this matter to the king. I request the king to signify by the bearer of this letter his wishes concerning Einion [Asaph] coming to him”.

It is difficult to know the truth of this charge. Possibly Asaph cooked it up: he knew how to push Edward's buttons, and that Llywelyn had fallen behind on the treaty payments. He also knew that war was looming, and had no intention of backing the weaker party.

Published on November 16, 2021 03:54

November 13, 2021

Spies and traitors

The Hagnaby chronicle for 1295:

The Hagnaby chronicle for 1295:“Item, on the same day in South Wales (March 1295) the messenger of the earl of Hereford, who was Welsh, fraudulently came to the Welsh, who were assembled in one column, as eight hundred, and he said to them: ‘The English are going out to seize booty: come wisely and capture those men for nothing’. They believed the words of this deceiver, and they came against the English in battle, but were deprived of their desire, because thanks to God they all fell to the English sword.”

This chronicle was only translated in the 1990s by Michael Prestwich and his colleagues. It is partially illegible, but the sections that can interpreted cast fresh light on the wars in Wales and Gascony.

The above entry reports a massacre in south Wales, towards the end of the revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5. It is supported by an entry in the Annales Monastici, which describes the earl of Hereford breaking the Welsh siege of Abergavenny at this time.

The interesting bit – setting aside the gloating tone of an English chronicler – is the reference to a Welsh spy. Who was this turncoat, who lured eight hundred of his fellow countrymen to their doom?

Until recently, it was thought that the Welsh revolt in Glamorgan and Gwent was led by Morgan ap Maredudd. David Stephenson has discovered that the Welsh of Gwent were in fact led by another man, a former royal tax collector named Meurig ap Dafydd. This is shown by a brief entry in a version of the Brut:

“Item: the Welsh of Gwent made Meurig ap Dafydd their lord”.

Neither of the English chronicles name the defeated Welsh commander at Abergavenny. However, since the town lay in Gwent, it is most likely that Meurig was in charge.

We know, from previously misdated correspondence, that Morgan ap Maredudd served as Edward I's spy on the Welsh Marches. Exactly how long he was in royal service is unclear, but we can take an educated guess. Virtually alone of Welsh leaders, he suffered no punishment for fighting against the king in 1282-3 and 1294-5.

Before we yell “TRAITOR!”, it might be considering Morgan's background. He was the heir of Maredudd ap Gruffudd, a lord of Glamorgan. In 1270 Maredudd was violently dispossessed of almost all his lands by Gilbert de Clare. After his father's death, Morgan was summoned to Snowdonia to do homage to Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. As soon as he had sworn the oath, Llywelyn ejected him from his last land of Hirfryn. There was no pretext or trial: it was simply done, for no other reason than Llywelyn was in a position to do it.

In the space of a few years, Morgan's family had been brutally disinherited by two greater powers, the Earl of Gloucester and the Prince of Wales. His resentment lingered, unsurprisingly, and he devoted the rest of his career to undermining them both.

I have no evidence that Morgan was the spy who lured Meurig's men into a trap in March 1295. But if we read between the lines – as I was severely instructed the other day – it all fits. Morgan was the man on the spot, he was a royal agent, and his career afterwards went from strength to strength. He eventually died in the 1330s, old, rich and respected. And full of secrets.

Published on November 13, 2021 03:59