David Pilling's Blog, page 17

October 11, 2021

Pious exclamations

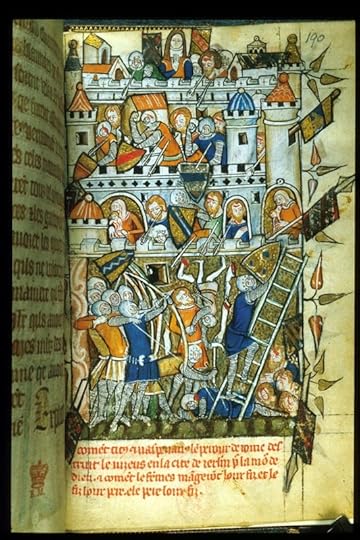

On 11 October 1270 the English and Scottish crusaders under Lord Edward landed at Tunis in North Africa. The leader of the crusade, Saint Louis of France, had sailed before them along with Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily.

On 11 October 1270 the English and Scottish crusaders under Lord Edward landed at Tunis in North Africa. The leader of the crusade, Saint Louis of France, had sailed before them along with Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily.It seems Louis was in no fit state. According to his biographer, Joinville, he was too sick to wear armour or remain long on horseback. Joinville even claimed that he had carried the king in his arms on one occasion, because Louis was too feeble to walk.

Even so, the French king insisted on leading another expedition to the Holy Land. For all his striving, Louis would never see Jerusalem. While camped outside Carthage, his army was stricken by dysentery. The king contracted the disease, as did his eldest son Philip, along with malaria. On 25 August Louis had himself laid on a bed of ashes and died in agony of body and soul. His last words are recorded:

“Lord God, give us grace to have the power of despising and forgetting the things of this world, so that we may not fear any evil.”

When Edward arrived, several weeks later, command of the crusade had passed to Charles. The expedition itself, so carefully planned and organised, had fallen apart. Apart from the English and Scots, the contingents from Flanders, Italy and Germany were also behind schedule.

The crusaders had landed in North Africa to attack Carthage, held by the Muslim Emir of Tunisia, Muhammed al-Mustansir. After the death of Louis, the more pragmatic Charles adopted a different policy. To the dismay of other Christian leaders, he entered into talks with the emir. In exchange for the departure of the crusaders, Muhammed agreed to pay a hefty ransom. This included an annual tribute to Charles, release of Christian captives, and the toleration of some missionary activity by certain religious orders.

English chronicles make much of Edward's disgust at the treaty. Some exclamations of suitably pious horror are put into his mouth, but there were more practical concerns. He and other crusade leaders, including the Count of Flanders and Duke of Luxembourg, had signed contracts with Genoese seamen. The Genoese had agreed to transport and return the crusaders only once. Charles's proposal to deliver the entire force to Sicily for the winter meant that everyone had to take out new contracts. This was expensive, and Charles compounded the problem by refusing to share the emir's tribute among his allies.

In spite of protests, the treaty went ahead and was sealed on 1 November. A few days later the entire Christian fleet sailed for Trapani in Sicily. To the satisfaction of English chroniclers, a storm blew up and sent Charles's ships, carrying the emir's tribute, straight to the bottom:

“All the money of the Berbers was lost. The vessels of Edward, in the centre of the others, were saved as if by a miracle...being spared very deservedly because he alone had not desired the money of the Berbers. He had only desired to restore to the Christians, as far as he was able, the land stained with the blood of Jesus Christ.”

- Westminster chronicle

Published on October 11, 2021 03:48

October 9, 2021

Frantic action

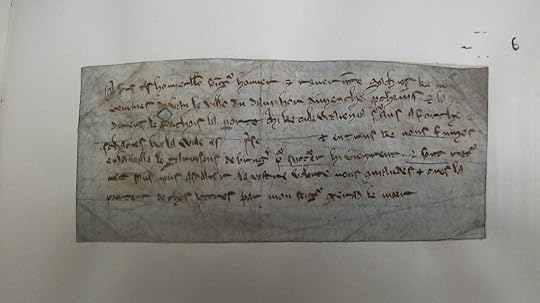

9 October 1297. On this day Jean de Chalon, a lord of eastern Burgundy, sends two letters to Edward I at Ghent. He informs the king that Jean and his followers have stormed the castle of Ornans and slaughtered the French garrison:

9 October 1297. On this day Jean de Chalon, a lord of eastern Burgundy, sends two letters to Edward I at Ghent. He informs the king that Jean and his followers have stormed the castle of Ornans and slaughtered the French garrison:“Most dear sire, this is to inform you, that on Tuesday, the eve of the feast of Saint Denis, myself and my companions of Burgundy captured and razed the castle of Ornans, which was held by Burgundy of the King of France and was the strongest castle in the whole of Burgundy. And know that, I and my other comrades broke down the walls of the castle and forced our way inside, and secured the castle, and took nine prisoners and put a large number to the sword, apart from those who threw themselves down below the rock.”

In the second letter, written hastily after the first, Jean adds that French reinforcements have arrived in Burgundy. Thus, Jean cannot leave to join Edward in Flanders as quickly as he would have liked.

Edward's fortunes have improved slightly, but his position is still fragile. Two-thirds of Flanders has been overrun by the French, and his allies will not reach him before the middle of October at the earliest.

To add to his problems, some of his allies are now fighting each other. Jean de Chalon's brother, Hugh, Bishop of Liége, is at war with Duke John II of Brabant over the city of Maastricht. Both men are also part of Edward's coalition against the French. Duke John, a noted Anglophile, is with the king at Ghent:

“The Duke of Brabant was also there

with many men, as you should know,

from his land, and also with many

from the borders of the Meuse, many a lord,

and also from the Rhine.”

For the umpteenth time in his reign, Edward is asked to step in and resolve a dispute. He sends another of his capable agents, Aymon de Quart, to mediate between Hugh and Duke John. While messages go back and forth, a battle rages in the streets of Maastricht between supporters of the rival parties. A local chronicle describes the conflict:

“A dispute arose in Maastricht between the bishop's and the duke's men, because the duke's party were greatly oppressing our people. By no means able to bear this harassment for long, they rose against the Brabanters, and, behold, a great battle took place between them. But since the bishop's party grew ever smaller and the duke's increasingly larger, our men were unable to fight for long and were brought to the point of total surrender. Wherefore, the Brabanters split them up, killing or wounding some and taking others prisoner. The rest fled wherever they could.”

From this it appears Duke John's men win the battle. It occurs in early October: on the 10th Hugh writes a letter to King Edward, complaining of the hostile acts of the Brabanters.

The king perseveres with his diplomacy. At the same time one royal eye is anxiously watching the German border for any sign of another ally, Adolf of Nassau. The other looks south-west, towards the French army encamped at Ingelmunster. Will Philip the Fair advance to offer battle, or stay put? No doubt to Edward's relief, the French don't budge.

Thanks to the frantic efforts of Aymon de Quart, the war in Liéges is quickly resolved by arbitration. His competence is hailed on both sides. He is yet another of the many Savoyards who entered Edward's service as soldiers, diplomats and engineers. Appointed canon and provost of Beverley Cathedral in Yorkshire in 1295, he will go on to become Bishop of Geneva.

Published on October 09, 2021 04:16

October 8, 2021

Greasy palms

8 October 1297. On this day Henri III, Comte de Bar – known on the German side of the border as Heinrich III von Bar – sends a letter to his father-in-law Edward I. He apologises for not responding earlier to the king's summons, but he was absent from Bar when it arrived. Henri is now raising soldiers as quickly as possible, and will march from Stenay to join the king at Ghent within a few days.

8 October 1297. On this day Henri III, Comte de Bar – known on the German side of the border as Heinrich III von Bar – sends a letter to his father-in-law Edward I. He apologises for not responding earlier to the king's summons, but he was absent from Bar when it arrived. Henri is now raising soldiers as quickly as possible, and will march from Stenay to join the king at Ghent within a few days. Stenay lies within the province of Bar, an outlier state of the Holy Roman Empire, about halfway between Rheims and Luxembourg. Ghent in Flanders is about 150 miles away, so Henri and his men will have to shift.

In his letter Henri mentions that Count Amadeus of Savoy is with him. The role of Amadeus in this conflict is a shadowy one. Although on Edward's payroll, he shuttles back and forth between the English and French courts, acting as adviser to both kings. This might seem odd, since England and France are at war, but it seems the count is being employed as an unofficial go-between.

Ultimately, it is neither Edward or Philip the Fair's interest to destroy each other. While the two kings beat their chests in public and make aggressive noises, their agents are scuttling about in the background, greasing palms, exchanging hefty bribes, arranging this or that favour for milord and messire. The one thing everyone wants to avoid is a pitched battle. Battles are far too unpredictable, and where's the profit in mindless slaughter?

Away from the present tense, much of this cloak-and-dagger work has only come to light recently. A current research project at Antwerp university is studying the role of English agents such as Robert de Segre, Jean de Cuyck and Count Amadeus, as well as King Edward's relations with the princes and merchants of the Low Countries. The subject is fiendishly complex – one is left with the impression that these men rather enjoyed it. Like a massive game of chess.

Published on October 08, 2021 03:50

October 7, 2021

Bare legs and a red skirt

In early October 1297, after several weeks of nothing very much, the war in Flanders flared into life again. From their base at Ghent, Edward I and his ally Count Guy Dampierre sent an army to recover the port town of Damme, adjacent to Bruges.

In early October 1297, after several weeks of nothing very much, the war in Flanders flared into life again. From their base at Ghent, Edward I and his ally Count Guy Dampierre sent an army to recover the port town of Damme, adjacent to Bruges.The French had captured Damme in September, cutting off the steady flow of supplies and reinforcements from England. It had to be retaken, otherwise Edward's men would starve. Once the port was recovered, the plan was to sweep on and storm Bruges, which the citizens had recently surrendered to Philip the Fair.

Damme was defended by 400 French troops and about 300 pro-Capetian Flemings. The population, like the rest of Flanders, was split down the middle between those loyal to Count Guy and 'the party of the Lily', who chose to support the French. After occupying the town, Philip's soldiers had indulged in the usual rape and pillaging, which was no way to win hearts and minds.

On the morning of 6 October an English knight, Sir Robert Scales, appeared before the gates of Damme. He was accompanied by another knight and six squires. While the defenders looked down at him, scratching their heads, Scales trotted forward and raised his banner.

This was the signal to attack. Several thousand Welsh, English and Flemish shock troops came howling out of the dawn mist and surged over the walls. The defences were incomplete, although the French had started work on refortifying the town. According to the Annalist of Ghent, they stretched heavy iron chains across the streets as protection against cavalry.

Clever, but no good against infantry. The pro-Guy supporters inside Damme helped the allied soldiers over the ditch and timber rampart, and a fierce battle erupted inside the streets. Most of the French were massacred, with a handful of survivors taken prisoner.

The allies were now poised to attack Bruges. Unfortunately a fight broke out in a tavern between a Fleming and a German mercenary. The other Flemish soldiers piled on the side of their countrymen, while the Welsh and English sided with the German: it appears the Irish sensibly stayed out of it. When the fight was over, forty Flemings lay dead and any chance of capturing Bruges was gone. Edward's marshals moved in to restore order – after the event, like good little policemen – and the town secured.

King Edward received a report of the action on 10 October. He must have groaned at the account of the brawl, but it wasn't a disaster. At least Damme was retaken, and the direct link with the Channel re-established. It was also one in the eye for his rival King Philip, who up until this point had had things all his own way.

A separate report reached Count Guy, sent by one of his knights, Gerard de Moer. This hastily scribbled note survives (attached) and informs Guy that the Welsh infantry had repaired the fort at Damme. Splendid multi-taskers, those Welsh.

The account of the Flemish war, by Lodewijk van Velthem, contains the famous description of Welsh soldiers:

"One saw there truly wondrous things

among the Welshmen:

they all went with bare legs

and all with a red skirt.

That was also the case in winter,

I am sure that this did not very well warm

the men who went there in such manner.

The money that [they] received from the King

was almost entirely spent on buttermilk, as I hear;

they ate and drank everything they found.

I never heard that these folks

were given weapons.

Nevertheless I observed many of them enough,

and also walked among them there,

to know the truth about them.

It is not that they armed themselves

as if they wanted to fight someone,

with bows, arrows and swords;

his was there their means of defense:

javelin and linen cloth,

those were the things there

that they had for their defense.

They drank very voraciously."

(Translation by Dr Jan Burgers; edited by Dr Kelly Devries)

A darker episode followed. Those citizens who had fought for Guy were promoted to aldermen. Guy also sent a team of inquisitors to 'question' those inside Damme who had supported the French. The record is ominously silent on the nature of this interrogation, and whether it involved red-hot pokers.

Published on October 07, 2021 03:51

October 6, 2021

Big face, big ambitions

Part of the effigy of Charles of Valois (1270-1325), a man with a big face and big ambitions.

Part of the effigy of Charles of Valois (1270-1325), a man with a big face and big ambitions.Charles was arguably the man who triggered the Hundred Years. Brother to Philip the Fair, he hated the Plantagenets for (unintentionally) shafting his chances to become King of Aragon. He had been invested with the kingdom by the papacy in his teens and, in the words of one historian, 'never quite recovered from the experience'.

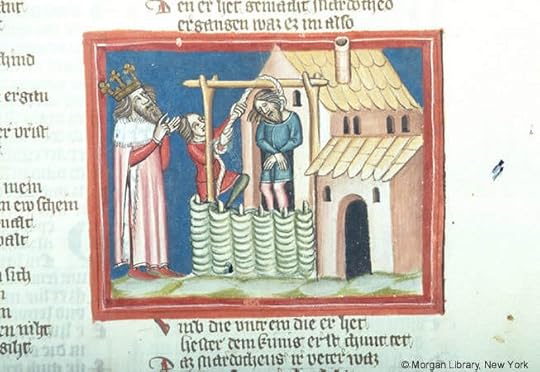

The disastrous French invasion of Aragon in 1284-5, the so-called Aragonese Crusade, was conducted in Charles's name and on his behalf by his father, Philip the Hardy. It was an utter disaster and ended with the French army being hounded through the Pyrenees and chopped to pieces by the 'Almogavars', Aragonese light infantry. Philip died soon afterwards, possibly of embarrassment.

Apart from French military defeat, Charles had cause to resent the role of Edward I, who had contracted a marriage between his daughter and Alfonso of Aragon. Edward's consequent arbitration of the Angevin-Aragonese dispute effectively deprived Charles of his claim to the throne, and left him 'Carlo senza Terra' – Charles the Landless, as Italian chroniclers gleefully pointed out.

Charles did not formally renounce his claim until 20 June 1295. This was one year after the outbreak of war between England and France, and the French occupation of Gascony. Thus, his claim still held good when the war started, and he had a specific interest in south-west France. Back in 1285 the French invasion of Aragon had failed because they lost control of the sea. If Charles could gain control of Gascony, this gave him a landward point of entry to Aragon.

His direct interest is shown by Philip's decision to send Charles to drive the English from Gascony. He failed. Bayonne held out for Edward I, and Charles's army was stricken by an epidemic while laying siege to Saint-Sever. He eventually managed to take the town and led his plague-ridden army back north. As soon as his back was turned, the citizens invited the English back in. This is the problem with many conquests – one has to persuade the conquered to let you stick around.

Published on October 06, 2021 08:44

Folding fast

The Chateau Lézian at Castelnau-Riviere-Basse in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, southwest France. This 16th century chateau may (or may not) stand on the site of the medieval castle of Riviere-Basse, once held by the Plantagenet dukes of Gascony. It is difficult to trace the location of medieval castles and fortified manors in the old duchy of Gascony: there were hundreds of them, dotted all over the place. Many have either vanished or been renovated into country houses.

The Chateau Lézian at Castelnau-Riviere-Basse in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, southwest France. This 16th century chateau may (or may not) stand on the site of the medieval castle of Riviere-Basse, once held by the Plantagenet dukes of Gascony. It is difficult to trace the location of medieval castles and fortified manors in the old duchy of Gascony: there were hundreds of them, dotted all over the place. Many have either vanished or been renovated into country houses.In autumn 1305 the Count of Foix re-ignited his family feud with the neighbouring Count of Armagnc. He took an army into the latter's territory, burning and ravaging, and seized the castle of Riviere-Basse, among others. This was unwise, since the castles were held direct of the king, and such action was interpreted as an assault on the crown.

Foix's invasion was also badly timed, since the new pope, Clement V, happened to be present in Gascony. He and the seneschal, Othon Grandson, agreed it was necessary to 'act with energy and speed' to prevent the conflict spreading further. A troop of cavalry – 5 barons, 16 knights and 358 squires – were hurriedly assembled at Mézin in late August. Othon took command of these men and rode out to whip Foix to heel.

The count folded like a cheap suit. Before any engagement could take place, he got his mother and sister-in-law to visit the pope at Bordeaux and beg for mercy. This was granted, on condition that Foix paid damages and submitted entirely to the will of the pope and seneschal.

War had been averted, but only temporarily. One of the major threats to the peace in Gascony was internal wars, especially the custom of single combat and blood-feuds between rival houses. Whoever ruled Gascony inherited these problems, which were insurmountable.

The situation was almost ridiculous: when the Foix-Armagnac feud started in the 1280s, it was the responsibility of Edward I. When Gascony was overrun by the French in 1294, it passed to Philip the Fair. Unlike Edward, Philip did not prohibit single combats, and agreed to preside over a duel between the rival counts. He then changed his mind – shades of Richard II – and threw down his baton to stop the fight soon after it began. This was lucky for Foix, since he had already fallen off his horse.

When the English recovered Gascony in 1303, the tiresome feud once again became their problem. Edward's very capable seneschal, Othon, managed to keep a lid on it, but the thing would rumble on into the reigns of the next two Edwards and the Hundred Years War.

Published on October 06, 2021 04:11

October 4, 2021

Travelling hopefully

I just got back from the 'Murder of Evesham' conference in Evesham, held over the weekend by the Mortimer History Society. A great day and some fascinating talks. While there I bought several recent translations of medieval chronicle accounts of the battle. The most interesting – startling, even – is that of Guillaume de Nangis.

I just got back from the 'Murder of Evesham' conference in Evesham, held over the weekend by the Mortimer History Society. A great day and some fascinating talks. While there I bought several recent translations of medieval chronicle accounts of the battle. The most interesting – startling, even – is that of Guillaume de Nangis.This is what Nangis has to day of the prelude to the battle:

“Edward and the Earl of Gloucester sensing therefore that help from the son to the father was nullified, assembled eleven men to breach his [Earl Simon's] security. It was indeed their intention to rescue the King, whom the said Simon led around with him as a captive, from his hands and to behead Simon himself as the prime mover of evil and disturber of the peace, as they said, and his sons Henry and Guy with the sword of vengeance. But Edward considered that in his opinion it was preferable that they be captured rather than killed to which the rest of the nobility unanimously agreed.”

I wish to focus on this passage and Nangis's claim that Edward wanted to spare the lives of Simon and his followers. This contradicts the usual interpretations of the battle, which generally derive from Edward's modern image of a ruthless king who wantonly butchered his enemies.

Who was Nangis, and why should he trust his work? He was a French monk, probably from Nancy in north-east France, and worked as the archivist of the abbey of St Denis (about five miles north of the centre of Paris) from c.1275-1300. He was the author of three biographies of successive kings of France.

His account of Evesham is taken from his biography of Louis IX, which Nangis commenced in about 1285. This was not strictly an original work, as Nangis acknowledged it as a continuation of an earlier work by Gilon de Reims. Thus the account is roughly contemporary, and probably derived from an earlier source. Unfortunately the work of Gilon de Reims is lost, but from other continuations we know that Nangis was scrupulously accurate.

Where did Nangis get his information? The modern translator, Tony Spicer, makes two suggestions. One, as an archivist, Nangis may have had access to reports of the battle that reached Paris. Second – and more intriguing – he may have obtained eyewitness accounts of the battle. The most probable source in this respect is the de Montfort family itself. We know that Simon's wife Eleanor and her children all took refuge in France after the battle. One of the sons, Amaury, is of particular interest. He was about the same age as Nangis, and both were in holy orders. It is quite feasible that Amaury visited St Denis at some point and gave Nangis his account of the battle.

None of these people, Nangis included, could be described as admirers of Edward. Thus, if they say he wanted to spare the Montfortians, there is no particular reason not to believe it. Apart from casting a slightly different light on Edward's character, Spicer also makes the following remark on the future king's status at this point:

“Nangis says that Edward decided that Simon and his sons should be captured rather killed to which the rest of the nobility agreed. This did not in fact save Simon or Henry and is possibly an indication that Edward did not have complete control over the men under him and was the head of a coalition of Gilbert de Clare, Mortimer and others rather than the supreme commander.”

This also jives with my personal opinion that Edward knew nothing of the conspiracy to kill Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in December 1282. The surviving private correspondence of John Peckham strongly suggests as much, as does Edward's reaction in the following years. It was a Mortimer plot, entirely organised and implemented by the Mortimer brothers, Edmund and Roger of Chirk. The revelation that their father, Roger senior, may well have overruled Edward at Evesham places this ambitious, hard-nosed Marcher family, with the blood of English kings and Welsh princes in their veins, squarely in the spotlight.

Added to all this are other chronicle accounts of Edward shedding tears at the funeral of his cousin, Henry de Montfort. Strange behaviour if he had given the order for Henry and his family to be wiped out.

One doesn't have to believe Nangis, of course. But his account is of interest and worthy of discussion. As for Edward, populist impressions of this particular Plantagenet are so firmly engraved in so many brains it is probably futile to call for re-assessment. Yet it might be worth bearing in mind the words of that great modern Welsh historian, RR Davies, when he turned his pen to Edward I and Wales;

“Questions like these cannot be readily, nor ever conclusively, answered. In history the best we can do is travel hopefully. But is is by travelling hopefully rather than by standing still, by asking new questions, by posing new connections, by probing our sources in different ways and by recognising their shortcomings that we advance and enrich our historical understanding.”

Published on October 04, 2021 07:34

September 30, 2021

Spinning plates

On 30 September 1297 Adolf of Nassau, King of the Romans and of Germany, sent Edward I a letter sealed with Adolf's private seal. This was the equivalent of top-secret – for Edward's eyes only.

On 30 September 1297 Adolf of Nassau, King of the Romans and of Germany, sent Edward I a letter sealed with Adolf's private seal. This was the equivalent of top-secret – for Edward's eyes only.In this case it must have been very secret. The letter is brief, and merely bids Edward to believe Adolf's message, as conveyed by word of mouth via the German king's clerk, William.

This mysterious missive was dispatched from Sinzig in the district of Ahrweiler on the River Rhine, quite close to the Franco-German border. Adolf had just escaped the clutches of the Bishop of Strasbourg, who had defected to the French, and was trying to scrape enough soldiers together to lead into Flanders.

Adolf may have been willing, but his position in the empire was falling to pieces. Six days earlier the bishop of Salzburg had made contact with Duke Albert of Austria, Adolf's French-backed rival, and offered to defect.

While Edward spun plates in Flanders, it was left to the regency council in England to cope with the aftermath of the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge. William Wallace and his followers cleared Scotland north of the Forth of English officials – with the doubtful exception of Sir Alexander Comyn - and set about retaking castles. Stirling, the key stronghold on the Forth, was forced to surrender. Sir William Ros, an English knight, and two of his companions were imprisoned in Dumbarton Castle “where he lay in irons and hunger and danger of death.”

The English response got underway in October. Despite being culpable for the disaster at Stirling Bridge, Earl Warenne was in command. An impossible force of 30,000 infantry was ordered to muster at Newcastle. Of these, only the North Welsh contingent of 5157 came close to filling its quota.

At the same time Edward had almost 7000 Welsh infantry quartered at Ghent in Flanders. A large number of these were also from North Wales. Given the compressed timeframe – Edward had fought three big Welsh wars in 1277, 1282-3 and 1294-5 – how many of these men had once fought against the king?

Published on September 30, 2021 05:19

September 29, 2021

Broken kinships

On 26 July 1298, four days after the battle of Falkirk, the Justiciar of North Wales claimed compensation for loss of horses in his military retinue. This consisted of the justiciar himself, John de Havering, and twenty-four soldiers. The claim was made at Stirling on the River Forth, which Edward I had rushed to secure after the battle.

Among Havering's retinue was Brother Ednyfed, Master of the Knights Hospitaller in Wales and commander of the houses at Ellesmere and Halston. Havering's men also included Gwilym de la Pole, his brother Gruffydd, Einion ap Ieuan, Meurig Atteben and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (not the late Prince of Wales, obviously). Gruffudd and Gwilym were two of the sons of Prince Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn.

Brother Ednyfed was a member of the kin-group called the Wyrion Eden, descendants of Enyfed Fychan, who had served as seneschal or 'distain' to Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. Ednyfed was a warlike man and frequently served the king in Wales and Scotland.

He first appears in December 1294, when he helped to suppress the revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn in North Wales. On 11 December Ednyfed received royal letters of protection for himself and his household, 'staying with the king in Welsh parts on the king's command'. Throughout December 1294-January 1295 he and Madog ap Dafydd of Hendwr received payments for loyalist Welsh infantry stationed at Penllyn inside Meirionydd.

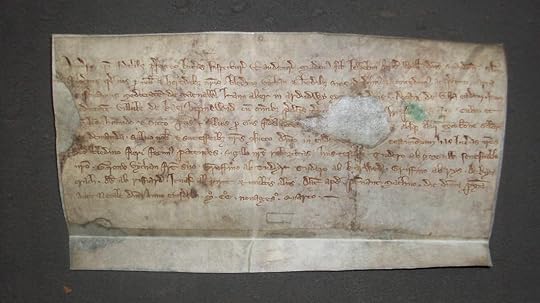

This conflict was, to a degree, a family feud. While Brother Ednyfed stayed loyal to Edward I, several of his kin joined Madog. Two of these were Tudur and Goronwy, grandsons of Ednyfed Fychan, who witnessed Madog's sole charter (pictured) as Prince of Wales, dated at Penmachno on 19 December. On the same day the charter was drawn up, Brother Ednyfed was with Edward at Derwen Llanerch, where he received £100 to pay his soldiers.

The Hospitaller survived the war in Wales, and the battle at Falkirk. He served again in Scotland in 1303-4, where his name appears among a list of 21 men drawn from North Wales. On this occasion Brother Ednyfed was again leading Welsh infantry, paid 12 shillings for his expenses and the expenses of his squire for four days, at three shillings per day. His name appears three times on the list, but does not appear on the fourth round of payments at Carlisle from 28 June-1 September 1304. It is possible he died or was killed on service.

Published on September 29, 2021 06:03

September 28, 2021

The last prince

On 28 September 1284 Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Ystrad Tywi in south Wales, forced seventeen local gentry to put their seals to an indenture. Via this agreement, they swore allegiance to Rhys on penalty of loss of lands and goods if they ever broke faith.

On 28 September 1284 Rhys ap Maredudd, lord of Ystrad Tywi in south Wales, forced seventeen local gentry to put their seals to an indenture. Via this agreement, they swore allegiance to Rhys on penalty of loss of lands and goods if they ever broke faith.The first name on the document is Madog ab Aradwr. This implies Rhys was particularly anxious to secure his allegiance. The explanation probably lies in Madog's previous career. He was an active partisan of the crown: in May 1277 he acted as surety for Rhys Wyndod when the latter borrowed 20 marks from Pain Chaworth, lord of Kidwelly, and served as a royal tax collector in the new Welshry being organised at Dinefwr.

Rhys was using the same methods of control as his rival, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. The princes of Wales in this era struggled to retain the allegiance of the rising 'gentry' class in Wales, otherwise called freemen or uchelwyr. These men were becoming increasingly rich and influential, and sought to break free of traditional constraints.

Similar patterns can be detected all over Western Europe. In Gascony, for instance, the gentry had to be constantly appeased by the English crown, otherwise they would defect to the French. To that end Edward I deliberately sold off two-thirds of royal demesne (crown estate) in the duchy, retaining direct control of Bordeaux and the wine staple.

It was much the same in Wales. Men such as Madog, Gruffudd Llwyd, Morgan ap Maredudd, Hywel ap Meurig and his sons, Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn and his sons, the various lineages of Powys Fadog, the gentry of Mon/Anglesey – etc etc – could all make a choice of lords. To them, much like the Gascons, it made far more sense to have a distant lord in Westminster than a much closer one, who could exert greater control. That might cause some offence, given the current unpopularity of Westminster, but it was what it was. Nothing will be gained from pretending otherwise.

Rhys ap Maredudd tried to deal with the problem before it happened. No dice: the day of the princes was passing, and nothing they did could halt the slide. When Rhys finally revolted against Edward I in 1287, the men he had sought to bind turned against him. Madog ab Arawdwr joined the royal army and fought at the siege of Newcastle Emlyn with three Welsh sergeants on barded horses serving at a high wage of a shilling per day for ninety-one days.

Madog's sons – Madog Fychan, Treharne Howel, Rhys Cethryn - continued their father's policy. After the failure of Rhys's rebellion, he was reduced to a hunted fugitive. In 1292 Madog's sons caught him in the woods of Mallaen – ironically, the same place where he had forced their father to seal the indenture of 1284. Their prisoner was delivered up to the king and hanged on the common gallows at York. Thus died the last prince of the ancient house of Dinewr, destroyed by his own and executed like a common thief.

As a reward, the brothers were granted the township of Cil-san, valued at 40 shillings a year, for which they owed suit to the commote court of Catheiniog and a yearly rent of fourpence. They held it for almost 50 years until the township was bought up in 1339 by Rhys ap Gruffudd, a cousin of Gruffudd Llwyd and another crown partisan.

Published on September 28, 2021 04:37