David Pilling's Blog, page 19

September 16, 2021

Prince or no?

On this day in 1400 Owain Glyn Dwr is said to have declared himself Prince of Wales. This view has been challenged in recent years, notably in Studia Celtica and Dr Gideon Brough's recent biography of Owain. The Welsh leader did not, apparently, use the title until his alliance with the French in summer 1404.

On this day in 1400 Owain Glyn Dwr is said to have declared himself Prince of Wales. This view has been challenged in recent years, notably in Studia Celtica and Dr Gideon Brough's recent biography of Owain. The Welsh leader did not, apparently, use the title until his alliance with the French in summer 1404. Prior to that date, Owain's correspondence refers to himself as 'Lord of Glyn Dyfrdwy': for instance, a letter of October 1403 to Henry Don at Kidwelly. Nor did Owain mention his princely claim to Welsh, Scots and Irish recipients of his letters. If he was calling himself Prince of Wales at this time, it is impossible to believe the title would have been omitted. That would be akin to Henry IV forgetting to refer to himself as King of England.

The notion that Owain adopted the title in 1400 apparently stems from the chronicle of Adam of Usk, and two English legal proceedings. One explanation is that Usk was aware of the legal cases against Owain, in which the allegation of his seizure of the title was made.

Of the two proceedings, the best-known is the trial of a certain English lord of Shopshire, John Kynaston the elder. The trial is dated 25 October 1400, in which Kynaston and his followers were accused of robbery, horse-theft and stealing cattle. They were also alleged to have been in Owain's company during his brief September campaign of that year. The Welshman's adoption of the title Prince of Wales is mentioned in passing.

Unfortunately I do not have access to the original document, though it sounds well worth looking at.

A few interesting bones can be picked out of all this:

1) The references to Owain adopting the title Prince of Wales in 1400 stem almost entirely from English sources

2) Loyalties of the time were not strictly defined along 'ethnic' lines: for instance, John Kynaston was of mixed ancestry, but could hardly be described as a Welshman, any more than his neighbours Roger Lestrange or Edward Charlton

3) There is no proof that Owain Glyn Dwr called himself Prince of Wales until September 1404, at a politically advantageous time, and entirely contrary to the popular view.

Or, at least, that is what my reading of the subject tells me. This isn't 'my' era at all, so I may well have misunderstood or missed other evidence. It's worth highlighting, at any rate.

(As an aside, John Kynaston's outlawed descendant, Humphrey, would become famous in the reign of Henry VII as Shropshire's answer to Robin Hood)

Published on September 16, 2021 05:07

September 15, 2021

Bankrupt regimes...

“Foreign adventurism is the last resort of bankrupt regimes.”

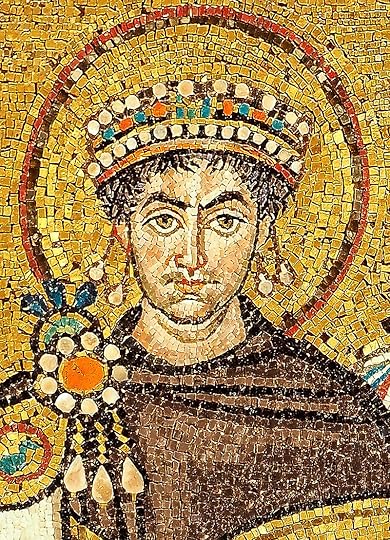

“Foreign adventurism is the last resort of bankrupt regimes.”This is a quote from an interesting documentary series on the Caesars I've been watching on Amazon. It relates to the 5th century emperor Justinian I and his decision to try and reconquer the western Empire; specifically, the lost provinces of North Africa and Italy.

Justinian couched his plan in terms of reconquering imperial territory from barbarians. In fact, as the doc points out, the Vandals and Goths who occupied these places had adopted classical Roman styles and become more 'Roman' than the Romans, who had long since adopted Greek customs.

The emperor's policy was really a desperate effort to give his ailing regime a shot in the arm. After a string of riots, plagues and not very successful wars, Justinian was about as popular as dung pie. If he didn't boost his public image, he was for the chop: the penalty of failure in the late Roman Empire was always death.

Lucky for him, the campaign in North Africa was a stunning success. This was due to Justinian's general, Belisarius, who defeated the Vandal king in two pitched battles and took him prisoner. He was then paraded through the streets of Constantinople. Belisarius was then sent to Italy, where he enjoyed initial success before the expedition ran into trouble. Part of this was due to Justinian, who had grown wary of the general's influence. To keep Belisarius on a tight leash, the emperor deliberately starved him of troops and supplies.

Even so, enough land and loot had been seized to give Justinian's tottering regime a much-needed polish. I'm sure we could think of a few more recent parallels...

Published on September 15, 2021 09:37

Hearts and minds

In August-September 1282 the Earl of Pembroke, William de Valence, embarked on a roughly circular march through West Wales. He started at Carmarthen on 16 August, moved northeast up the Tywi valley to Dinefwr, and then up and round to Llanbadarn, finally arriving at Cardigan via the coast road on 6 September. Here the army was disbanded and payments made for men to stay and round up cattle, presumably for supplies.

In August-September 1282 the Earl of Pembroke, William de Valence, embarked on a roughly circular march through West Wales. He started at Carmarthen on 16 August, moved northeast up the Tywi valley to Dinefwr, and then up and round to Llanbadarn, finally arriving at Cardigan via the coast road on 6 September. Here the army was disbanded and payments made for men to stay and round up cattle, presumably for supplies.What was the purpose of this expedition? Historians give confused explanations. Michael Prestwich said that Valence was seeking to engage the Welsh in battle, but failed to track them down. J Beverly-Smith, on the other hand, argued that Valence's march had 'shattered the power of the princes of Ystrad Tywi'.

The details of the payroll for Valence's army tell a different story. Several years ago I had this document translated in full at the National Archives. As a typical record of administration, it isn't the most compelling read. Nevertheless, it is full of detail and the best contemporary source document we could wish for.

Valence was appointed commander of the army in the west on 6 July. This was after the disgrace of his predecessor, Gilbert de Clare, who had split his army and led it to defeat at Llandeilo Fawr. The roll shows that Valence was not seeking battle: rather, he meant to drive a wedge between Llywelyn ap Gruffudd's allies in West Wales and the tenantry on their estates. Obviously, if they had no men, Llywelyn's supporters could do little harm.

To that end Valence marched about hostile districts and brought their inhabitants back to the king's peace. This was not, apparently, done through intimidation or violence: instead the men of local commotes agreed to enlist in his army. At the same time it was a dangerous operation. Unlike his predecessor, Valence took care to march in cautious stages, deploy scouts and cut paths through the deep forest ahead of his line of march.

Perhaps the most significant entry is a payment to the Welshmen of Iscennen, close to the site of Clare's defeat at Llandeilo. This shows that 60 footsoldiers of the commote, led by the local freeman, Kediver ap Gogan, came into the king's peace and did military service for two days at a cost of 21 shillings. For such a limited period, this probably involved little more than marching up and down a bit.

It is quite likely that Kediver and his men had been part of the Welsh army that embarrassed Clare at Llandeilo in June. We know nothing of that army: Welsh chronicles have little to say about it, and none of the English accounts say that Llywelyn and Dafydd or their allies were involved. Since the Welsh must have had leaders, it is reasonable to suggest they were freemen like Kediver, a bit further down the social scale.

Published on September 15, 2021 04:07

September 13, 2021

Lords of the Mark

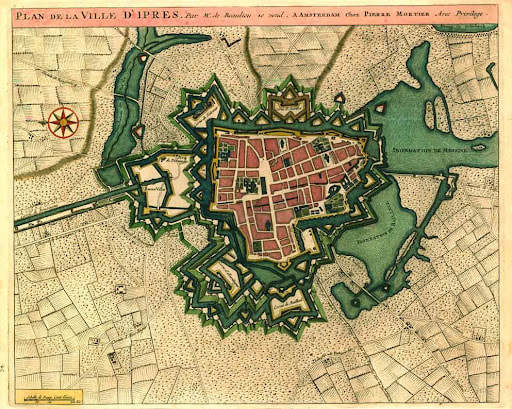

In summer 1297 Count Eberhard von der Mark and other German princes marched into Flanders to help Edward I and Count Guy Dampierre fight the French. Their task was to defend the city of Ypres in western Flanders:

In summer 1297 Count Eberhard von der Mark and other German princes marched into Flanders to help Edward I and Count Guy Dampierre fight the French. Their task was to defend the city of Ypres in western Flanders:“The same count Eberhard, with a company of chosen allies, knights and squires, chief amongst whom was the Count of Weldege, brought aid to Edward, king of England and Guy, Count of Flanders, and entered Ypres and held it, not without considerable peril to themselves.”

Chronik der Grafen von Mark (Chronicle of the lords of the Mark)

The contribution of the Germans is another neglected side-plot of the war in Flanders. Most, if not all of them, were on Edward's payroll. Count Eberhard had taken a fee of £500 English sterling and surrendered two of his castles in Germany to the king as a guarantee of service. Another German prince, Walerand of Falkenburg, took a smaller fee of 350 livres tournois.

They certainly earned their money. When King Philip invaded Flanders in the summer, only the Germans and the loyal followers of Count Guy stood in their way. Edward was unable to sail from England in time, while the King of Germany, Adolf of Nassau, was distracted by a revolt at home. Adolf sent all the help he could, but it wasn't enough to stem the tide.

Philip's forces stormed into Flanders. While the main French field army laid siege to Lille, smaller divisions spread out to waste the Flemish countryside. They set about burning townships, mills and farms and slaughtering the peasantry. In response a combined force of Germans and Flemings attempted to halt the French advance at Comines, a river crossing near Lilles.

The result, as the French chronicler Nangis gleefully reported, was a smashing French victory:

“Gui, count of, Saint-Paul; Raoul, Lord of Nesle, Constable of France; Gui, his brother, marshal of the army, with some others, having moved away from the army of four leagues, delivered combat to the enemies on the banks of the river of the town of Comines, put more than five hundred in rout, killed many, and captured their tents. They brought prisoners with them to the King of France many of the King of Germany's stipendiates, men of arms and famous knights.”

The surviving Germans fled back to Ypres, where they fired the suburbs to stop the victorious French capturing the town. A nightmarish battle followed, as the Germans and Flemish citizenry fought desperately to repel Philip's shock troops amid smoke and flame and the rubble of collapsing streets. As the fight raged, bands of looters took advantage to pillage houses and churches. The town of Vlamertinghe, a borough just outside Ypres, was burnt and gutted by Flemish thieves.

In spite of the utter chaos – or perhaps because of it – the French could not storm the town. After a bitter struggle, Philip's troops were driven back and forced to retreat. They left a smoking ruin behind them: for instance, the complete destruction of Vlamertinghe was mentioned for years after in the accounts of the chapter of St Peter of Lille. The French, however, had been kept out.

Published on September 13, 2021 04:24

September 11, 2021

New interpretations (2)

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where William Wallace and Andrew Moray met Edward I's captains 'in their beards' and won an astonishing victory. Thousands of Englishmen were slaughtered, including the treasurer Hugh Cressingham. Famously, Wallace is said to have made a belt of his skin.

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, where William Wallace and Andrew Moray met Edward I's captains 'in their beards' and won an astonishing victory. Thousands of Englishmen were slaughtered, including the treasurer Hugh Cressingham. Famously, Wallace is said to have made a belt of his skin.On the day of the battle Edward was at Ghent in Flanders, embroiled in a chaotic campaign against his cousin, Philip the Fair of France. When exactly he learned of the crisis in Scotland is uncertain, though the regency council in London had been informed by 26 September. News didn't necessarily travel slowly – especially important news – so the king may have been aware by the end of the month.

What followed is sometimes passed over, which gives the impression that Edward dropped everything to rush home and deal with the Scots. In fact there is no sign of haste or panic on the king's part, and for the moment he remained committed to the French war. It was left to his administration in England, headed by the Earl of Surrey, to mount a counter-offensive against Wallace (Moray died of his wounds soon after the battle).

This is where a bit of wider context helps. Edward and his ally, Count Guy Dampierre, were at Ghent waiting for the arrival of a German army led by the titular Holy Roman Emperor, Adolf of Nassau. Adolf, as my post yesterday pointed out, has often been misrepresented. Many historians have accused him of doing nothing to help his allies against the French, and effectively leaving Edward and Guy in the lurch.

In fact Adolf did all he reasonably could. On 18 September he was at Sélestat, near Alsace on the banks of the Rhine. From here he sent a letter to Count Guy, informing him that he could not come to Flanders to 'rescue' him from King Philip, because a revolt had broken out against Adolf in Germany.

The German king was in serious danger. While at Sélestat, he was informed that the Bishop of Strasbourg had defected to the French and was planning to ambush him. Adolf had to quickly board a ship with his family and sail to Germersheim, narrowly avoiding capture.

Although he was forced to scramble, the German king did not forget his allies. Unable to go to Flanders in person, he sent three of his nobles to fight instead. These were Henry, Count of Bar, his lieutenant Heinrich von Blammont and Count Eberhard, a German lord. Apart from their duty to Adolf, these men also had multiple loyalties elsewhere: the count of Bar was Edward I's son-in-law, while Heinrich held lands in Flanders of Count Guy. All three were also on England's payroll and had taken large sums of English money to fight the French.

Adolf took other measures. After his narrow escape to Germersheim, he ordered the baron or 'landvogt' of Alsace, Count Thibaut of Ferrette, to attack the French. Thibaut had also joined Edward's coalition against Philip in the summer. His nephew had recently been slain by French troops at Arles, so he had much to avenge. The count immediately obeyed and inflicted a crushing defeat on Philip's forces:

“Having assembled a strong army, he fell upon the French and did them great harm. At last his relatives in the country came and begged him not to strip them of their possessions and offered him a ransom of 5000 livres tournoise. He accepted their prayers and returned to Alsace.”

Annals of Colmar

Thibaut's action is another example of multiple allegiances in this era. As the landvogt of Alsace he was a vassal of the emperor; as a paid mercenary in the service of Edward I, he also had an English indenture or contract to fulfil.

With all this to contend with, it is no surprise that Edward could pay little attention to Scottish affairs. He would not return to England until March 1298, almost seven months after Stirling Bridge.

Published on September 11, 2021 01:37

September 10, 2021

New interpretations (1)

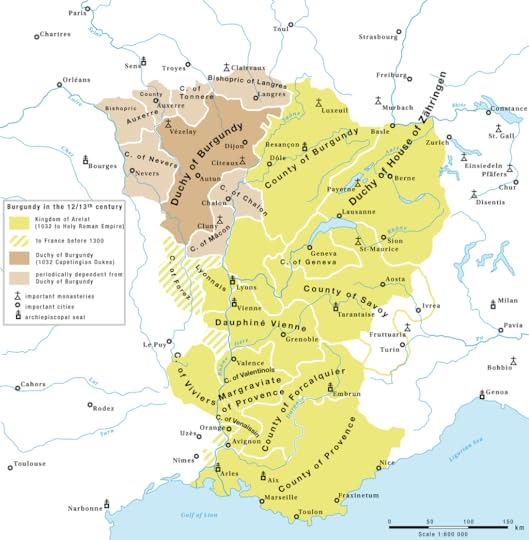

In late September 1297 Adolf of Nassau, King of the Germans, sent a letter to his ally Edward I. It translates, a little awkwardly as follows:

In late September 1297 Adolf of Nassau, King of the Germans, sent a letter to his ally Edward I. It translates, a little awkwardly as follows:“'The lord king, my lord the lord king of Germany, notifies your magnificence that his men are ready for the campaign and that those troops are ravaging his own territory. Therefore, since my said lord, the lord king, awaits your councillors, who can advise him as to how and by which route he should proceed, he prays your lordship that you speedily send those councillors to him for that purpose, so that by their instructions he may so proceed without delay to carry them out in all respects with dispatch.”

The campaign in question was the war against Philip the Fair, King of France. Although he was King of Germany and titular Holy Roman Emperor, Adolf was poor and could only afford to fight the French thanks to large English subsidies granted to him by Edward. Upon receipt of £40,000 of English money, Adolf raised an army.

In his letter, Adolf refers to his troops ravaging their own land. This is probably a reference to one of the many neglected episodes in this war, passed over by Anglophone historians.

According to the Dominican annals of Colmar, Adolf had previously received a plea for help from the citizens of Arles. This was the chief city of Provence and once part of the greater kingdom of Arles. In the eleventh century the kingdom had been incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire, but by Adolf's day it had largely been subsumed by France. It did not, however, formally become part of the Kingdom of France until 1481.

The expansionist Capetian king, Philip the Fair, had designs on Arles. In the autumn of 1297 he sent troops to conquer the city, which was all part of his wider conflict against England and Germany. When Adolf heard of this, he sent part of his army to defend Arles against the French. His troops were led by Theobald, son of the Count of Ferrete, and one Werner de Hadstadt.

Adolf's men arrived in time to save the city. After several weeks of fighting, the French were repelled. Then, unfortunately, his troops got bored and started to pillage Arles. This would appear to the context of Adolf's letter to Edward in September.

Edward in turn had a vested interest in Arles. Twenty years earlier his mother, Eleanor of Provence, and her sister Margaret, had attempted to press their claim to the ancient kingdom. Margaret even raised an army for the purpose, and demanded that her nephew get involved. She eventually agreed to sell her right in exchange for a pension, but the Plantagenet interest in Arles remained. If Adolf could secure the city, he in turn would owe Edward a favour: after all, without English money he had no military capacity whatever.

It might have worked, but then Adolf lost control of his soldiers. The despairing citizens decided to switch allegiance and contacted Philip, asking him to rescue them from their rescuers. If he would send his officers to take over, they offered to lure Adolf's men into a trap and butcher the lot. This would save Philip the necessity of fighting a battle.

Naturally, the French king agreed. The trap was duly laid and most of Adolf's men slaughtered, including Theobald and his lieutenant Werner. Philip then sent his magistrates to secure Arles. Their first action was to arrest and execute certain 'traitors' inside the city, which didn't do much to endear the French to their new subjects.

Adolf, as I shall describe in Part Two, was far from done. The point of these posts is to cast a new perspective on this subject, which (in my opinion) has been totally misrepresented. Part of the problem is navel-gazing – the tendency to study one country and treat the rest as incidental – while another is the difficulty of the source material. Most of this information comes from quite obscure non-English language sources, and is difficult to extract. But if the effort is not made, we are left flailing about in the dark.

(Many thanks to Rich Price, as ever, for his translation work)

Published on September 10, 2021 05:58

September 2, 2021

Mortimer matters

On 16 May 1297 the Welshmen of Maelienydd were summoned to parliament by Edward I to lay their grievances against their lord, Edmund Mortimer, before the king and council. Edmund was also summoned to appear in person to explain his actions.

On 16 May 1297 the Welshmen of Maelienydd were summoned to parliament by Edward I to lay their grievances against their lord, Edmund Mortimer, before the king and council. Edmund was also summoned to appear in person to explain his actions. Specifically, the Welsh complained that Edmund unjustly imprisoned them and took away their goods and chattels at will, so they were now so impoverished they had little or nothing to live on. One example of this is the plea of Cadwgan Goch of Arllechwed in 1283, who complained to the king that he was held in iron chains at Edmund's castle of Wigmore, even though he had been admitted to the king's peace and had royal letters of restitution to his lands in Cedewain.

As a result of the enquiry, Edmund was forced to provide the Welshry with charters of liberties. These were sealed at Wigmore in July and confirmed that none of the Welshry were to be unjustly imprisoned or disinherited; further, all pleas of land etc would be decided in court, rather than Edmund's whim, and the Welshry would have certain hunting rights. If they hunted on Edmund's land, they would pay a fine. If their dogs strayed onto his land, the animals would be returned unharmed. Any deer they brought down would go to Edmund.

And so on. The Welshry didn't get these liberties gratis: they had to pay the king £500 for the privilege, quite a sum for the time. They had no trouble finding the money, so perhaps not as impoverished as all that.

The context of this affair was Edmund Mortimer's opposition to the king in the spring of 1297. At Easter, shortly before the summons to parliament, he had held an assembly of disgruntled Marcher lords inside Wyre Forest, adjacent to Cleobury Mortimer. Here they discussed their grievances, principally Edward's grinding war taxes and demands for military service.

Edward used various tactics to split up the rebels. Some were bought off, others persuaded to return to the fold. Edmund was singled out for special treatment. This was the man who had destroyed Prince Llywelyn, and he was now holding conspiratorial meetings with powerful men on his estates. All very suspicious, and not to be tolerated. By forcing him to grant rights to the Welshry of Maelienydd, the king drove a wedge between Edmund and his tenants. Rendered toothless, Edmund backed down and agreed to send men to fight in Flanders.

Published on September 02, 2021 01:30

August 15, 2021

Rough stuff

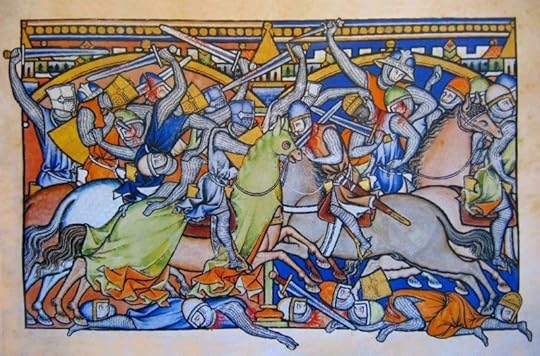

In August 1273 the armies of the Queen of England and the Viscountess of Limoges faced each other on an open plain between Aixes and the town of Limoges in southwest-central France. The ensuing battle, ignored by English histories then and now, is described by the Chronica Majora of Limoges:

In August 1273 the armies of the Queen of England and the Viscountess of Limoges faced each other on an open plain between Aixes and the town of Limoges in southwest-central France. The ensuing battle, ignored by English histories then and now, is described by the Chronica Majora of Limoges:“In the same year, on the day following the feast of Saint Sixtus, the king of England's seneschal, who had come to the aid of the citizens of Limoges against the viscountess of Limoges, had a great victory over her army, between Aixe and the town of Limoges. He wounded and captured many of them, killing a nobleman and many others, without loss to him or his allies, at which the townsfolk rejoiced greatly. Moreover, they captured the banner of Girbert de Tamines. On the feast of Saint Laurence following [two days later] one of the viscountess's men was found dead and many horses on both sides too, but the viscountess lost many more.”

It would be nice to report that Edward I's consort, Eleanor of Castile, led her troops in person: hot damn, Els Bels the Amazon! There's a bit of agency for you. But it seems not. Instead the royal army was led by the seneschal of Gascony, Luke de Tany. The result was a victory, followed up by another a few days later.

The battle occurred because the citizens of Limoges had previously written to Edward, asking him to come and be their overlord instead of the king of France, Philip III. This was because the citizens were at war with the viscountess, and Philip chose to support her over them.

Given Edward's reputation, one might expect he steamed in with all guns blazing. Not so: this was France, not the British Isles, and he had to step carefully. It was a long time since the Plantagenets called the shots on the continent: now, after the Treaty of Paris in 1259, they were merely Dukes of Aquitaine, just another of the magnates of the French crown.

At the same time Edward wished to exploit an opportunity, as he did elsewhere in his career. If he led the army in person against the viscountess of Limoges, he would be in clear breach of his fealty to Philip, and declared a rebel against the French crown. The solution was to send proxies: Eleanor was dispatched to sweet-talk the citizens, while de Tany was sent to do the rough stuff.

Published on August 15, 2021 03:50

August 13, 2021

Dark arches...

Holt Bridge over the River Dee near the England-Wales border. According to an old fable, two fairies haunt the bridge on moonlit nights at certain times of the year.

Holt Bridge over the River Dee near the England-Wales border. According to an old fable, two fairies haunt the bridge on moonlit nights at certain times of the year. This tale was inspired by the alleged fate of Gruffudd and Llywelyn, the young sons of Madog ap Gruffudd, lord of Powys Fadog. Madog died in December 1277, leaving a widow, his sons and three brothers. The brothers were Owain, Gruffudd and Llywelyn Fychan, the so-called Dragon of Chirk.

The boys are said to have been drowned under Holt Bridge by Earl Warenne and Roger Mortimer in 1282. This was after the conquest of Powys Fadog, whereby Bromfield and Dinas Bran were granted to Warenne by Edward I. The story goes that the king granted the custody of Madog's sons to Warenne and Mortimer, who quietly had the boys murdered. They were, after all, rival claimants to Warrene's new lordship.

What to make of this dark tale? Edward certainly granted Bromfield and Dinas Bran to the earl: the grant is contained inside the Calendar of Welsh Rolls and dated 7 October 1282.

If we scroll back a few years, a different picture emerges. On 10 December 1277 Edward granted the custody (wardship) of the boys to their mother, Margaret, who was also Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd's half-sister. In these years Margaret enjoyed the king's favour and appears to have had some influence at the English court.

The wardship became the subject of a family row. On 4 January 1278 Margaret complained to the king that her brother-in-law, Llywelyn Fychan, had unjustly invaded and occupied her land of Mechain. He did so because Mechain was part of the inheritance of his nephews, and he wanted the wardship instead of Margaret. This, she implied, was so Llywelyn could milk the revenues until the boys came of age. The king ordered an enquiry and justice done according to Welsh law.

Problems continued. The next year, 3 March 1279, the king ordered the justice of Chester to sack Margaret's bailiff, because he had been embezzling funds that should have gone to the maintenance of her sons. The exploitation of minors is a sadly persistent theme in this era of Welsh history.

So to the drowning. This story first appears in David Powell's History of Cambria (published 1584). All he said was:

'These guardians, forgetting the service doone by the father of the wardes to the King, so garded their wardes that they never returned to their possessions'.

This implies something horrid befell the boys, but Powell doesn't say what. His brief account was taken up by the likes of William Camden and Thomas Pennant, until a legend of murder and dark deeds became part of Chirkland legend. The tale of drowning originally stems from Pennant, writing in 1883, who wrote:

'This I discovered in a manuscript, communicated to me by the Reverend John Price, keeper of the Bodleian library'.

So far as I know, this mysterious MS has never come to light. Holt Bridge itself was built in 1348, decades after the boys were supposedly done to death under its dark arches.

If we deny the tale, there remains the actual fate of the two boys. They were certainly dead by 7 October 1282, when the king granted their lands to Earl Warenne.

The only tangible clue is the fate of their mother, Margaret. Prior to 1282, she had been on good terms with the king. In the winter of that year she appealed to Edward to have her lands, which she claimed had been taken unjustly by Warenne. This was shortly after the royal grant to the earl in October, and the death of her brother Prince Llywelyn at Cilmeri in December. Thus, when she made the appeal, her children were already dead.

Edward's response was brusque. The response to her petition states 'this woman has offended against the king to such an extent that the king is not held to do her favour'. Margaret was left with nothing. What she had done to offend the king is not described.

Allowing for exaggeration and tall tales, it seems most likely (to me, anyway) that the boys were killed in the autumn of 1282. Welsh males were considered of fighting age at twelve, and it may be they were slain in battle by Warenne's soldiers. Their actual ages in 1282 are uncertain.

Margaret must have been tough. Widowed, landless and childless, she wasn't for giving up. 18 months later she came again before the king and pleaded against Earl Warrene. By now the royal wrath had cooled somewhat. On 20 May 1284 Margaret was granted five marks a year 'as charity' for her upkeep; in a second grant, 22 October, she was given the rents of the towns of Bodunan and Hyrdref as a life grant. These amounted to £6 per annum. Enough to live in respectable comfort, though a far cry from her previous wealth and status.

She lived for another 15 years. On 15 April 1299 it was briefly recorded that the town of Bodunan was to be re-granted due to the death of the woman who was 'sister to Llywelyn, then Prince of Wales'.

Published on August 13, 2021 05:16

August 10, 2021

Giving up on Wales

August 1265, In the immediate aftermath of Evesham, the Lord Edward's first move was to race north to Chester to re-establish his authority there. Chester was part of the original appanage granted to Edward by his father, Henry III, back in 1254. To judge from his frequent visits and involvement in local affairs, Edward cared for the lordship almost as much as Gascony.

August 1265, In the immediate aftermath of Evesham, the Lord Edward's first move was to race north to Chester to re-establish his authority there. Chester was part of the original appanage granted to Edward by his father, Henry III, back in 1254. To judge from his frequent visits and involvement in local affairs, Edward cared for the lordship almost as much as Gascony. Contrast that to Wales. For a man whose most enduring military exploit was the conquest of Wales, Edward in his youth showed little enthusiasm for the place. His experience on campaign in the Perfeddwlad with his father in 1257 was a dispiriting one, and he allegedly suggested giving it up as a bad job:

“Nor did they [the Welsh] wish to obey Lord Edward, the son of the king, but they laughed boisterously and heaped scorn upon him. And so consequently Edward put forward the idea that he should give up these Welshmen as unconquerable.”

Matthew Paris, Chronica Majora

Paris cannot be trusted, but in this case the quote is supported by Edward's actions. In 1262 he had to be practically dragged back from Gascony to lead a not very successful expedition into North Wales, and three years later sold off his interests in Cardigan and Carmarthen to his brother, Edmund. This transaction was possibly motivated by an invasion of Cheshire by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd soon after Evesham. A scratch force was sent to repel Llywelyn, led by Edward's allies Hamo Lestrange and Maurice FitzGerald, only to be roundly defeated.

Edward seems to have concluded a military solution in Wales was impossible. After 1265 he switched to patching up relations with Llywelyn, and granted him the homage of certain Welsh lords. This was done in exchange for money to fund Edward's crusade, which Llywelyn never paid over, and to spite the 'red dog', Gilbert de Clare. To favour the Prince of Wales over an English earl only weakened English power in the principality, but Edward was unconcerned. He had washed his hands of Welsh affairs. For now.

Published on August 10, 2021 01:48