David Pilling's Blog, page 21

July 19, 2021

Folville's laws

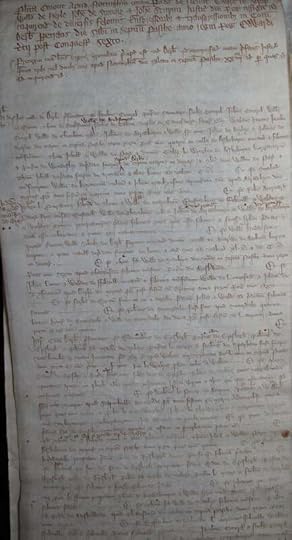

On the outlaw trail again, and I'm having more luck than the sheriff. Attached is the first membrane of JUST 1/1411B, a special commission of 1333 set up to deal with criminal gangs in England. The specific counties named are Lincolnshire, Rutland, Northamptonshire, Notts, Leicester and Derby.

On the outlaw trail again, and I'm having more luck than the sheriff. Attached is the first membrane of JUST 1/1411B, a special commission of 1333 set up to deal with criminal gangs in England. The specific counties named are Lincolnshire, Rutland, Northamptonshire, Notts, Leicester and Derby. The motive for this commission was the kidnapping of Sir Richard Willoughby, a justice of the king's bench and son of the chief justice of common pleas in Ireland. On 14 January 1332 Willoughby was ambushed on the highway by a gang of outlaws and spirited away into the forest to be held for ransom.

The commission names the culprits: James Coterel and his brothers, Eustace Folville and his brothers, John Bradburn, Roger Savage, and others. These were all the usual suspects, plus a host of lesser-known men. It seems the gentry gangs north of Trent had combined to pull off their most spectacular crime to date.

Willoughby was held for a ransom of 1300 marks (over £1000). Although motivated by financial gain, the outlaws may have also desired vengeance. The ringleaders had crossed Willoughby's path on many occasions. In June 1329 he had been entrusted with hunting down the Coterels, Folvilles and their ilk when they broke the parks of Earl Henry of Lancaster. On 26 January 1331 the earl again called upon Willoughby to pursue the Folvilles, while in October he pursued the complaint of Walter Can of Newton against the Coterels and Bradburns. This latter occasion was a squabble between clergymen: Walter Can was the rival of Robert Bernard for the post of vicar of Bakewell, and Bernard hired the gangs to attack his opponent.

James Coterel and his friends thus had good reason to target Willoughby. The man was a nuisance. Moreover, he was very rich and a fit subject for humiliation by men who claimed their own society and rule of law.

Willoughby was also unpopular. More than typically corrupt, he was accused of selling the laws of the lands “as if they were cattle or oxen”. Even so, the government was willing to cough up to get him back. The ransom was duly paid and shared out among the outlaws in Markeaton Park in Derbyshire on 2 February 1332. Oddly, the Folvilles only took 300 marks (of the 1300) while the Coterels got an even more modest 40. The lion's share probably went to Sir Robert Tuchet, lord of Markeaten, who often sheltered the outlaws at his castle.

The commission of 1333 was a serious effort to bring the gangs to book. Between 21 January and the end of March a steady stream of outlaws came before the justices; the Crown pursued every indictment and some men were required to appear two or three times.

The near-total impotence of the law was then exposed. Virtually all the suspects were acquitted, some because they were doing military service in Scotland, others for no stated reason. One man, William Uston, was allowed to walk even though he had already been sentenced to hang in September 1332. Since then he had dealt in forged money and served James Coterel as a spy in Nottingham, but still nothing was done.

Published on July 19, 2021 03:40

July 18, 2021

Funny money

In August 1270 Prince Llywelyn sent an appeal to Henry III, asking him to attend to the problems which were gathering in the March. In his response Henry commended the prince's goodwill, but answered that nothing could be done until the Lord Edward returned to England. Since the English prince was about to set out on crusade, and might well never return, Henry had effectively stonewalled Llywelyn's plea.

In August 1270 Prince Llywelyn sent an appeal to Henry III, asking him to attend to the problems which were gathering in the March. In his response Henry commended the prince's goodwill, but answered that nothing could be done until the Lord Edward returned to England. Since the English prince was about to set out on crusade, and might well never return, Henry had effectively stonewalled Llywelyn's plea. In the event Edward would not return for four years, by which time his father was dead. Before he left, he gave one last indication that he could resolve issues in Wales that Llywelyn felt bound to urge upon the king.

The matter in question was the homage of Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, lord of Ystrad Tywi and a descendant of the Lord Rhys. Maredudd had defected to the English during the recent 'great war' in Wales, and was the only Welsh baron not to pay homage to Prince Llywelyn when the treaty of Montgomery was negotiated. This was probably at his request: he had inherited an age-old feud between the houses of Dinefwr and Aberffraw, and had no desire to be a vassal of the prince of Gwynedd.

Yet his position was fragile. The treaty had stipulated that the king might choose to sell Maredudd's homage to Llywelyn for a fee of 5000 marks. Llywelyn had attempted to trigger this clause on 1 January 1268, only for Henry to firmly reject it. Two years later, the king relented thanks to the influence of Edward, who had persistently lobbied for the sale of Maredudd's homage to Llywelyn.

This was not altruistic: Edward needed money, and quickly, for his crusade, and 5000 marks would fill a large gap in his finances. At the end of August 1270 his trusted clerk, Robert Burnell, was sent into Gwynedd with the documents all prepared, though they would not be conveyed to Llywelyn until the entire sum was paid over.

It never was. The Patent Roll contains Henry's confirmation of the grant of homage and an instruction to Maredudd to pay homage to Llywelyn. There is no record of actual payment, and in 1277 Llywelyn offered the same amount to Edward I for the homage of Maredudd's son, Rhys. In the meantime it seems Maredudd was obliged to do homage anyway, and sold by the English to his worst enemy in exchange for a pile of funny money.

Published on July 18, 2021 02:01

July 17, 2021

Manly banter

In July 1274 the Little Battle or Little War of Chalon took place on the Saone in Burgundy-Franche-Comté. This was a tournament that turned nasty when the host, the Count of Chalon, tried in vain to unhorse Edward I.

In July 1274 the Little Battle or Little War of Chalon took place on the Saone in Burgundy-Franche-Comté. This was a tournament that turned nasty when the host, the Count of Chalon, tried in vain to unhorse Edward I.Tourneys in this era were rough affairs, and there was little to distinguish them from real battles. Combatants were often maimed or killed: for instance, Matthew Paris describes a high number of casualties at a tourney in Blyth in 1256. For a long while there was little effort at security or regulation, and violence sometimes spilled into the crowd. At a tourney in Rochester in 1251, Edward's uncle William de Valence and his men were beaten up with sticks and clubs by English squires.

These disorders often had grave political consequences. The assault on Valence was quoted by Paris as part of the growing hatred between the English and Henry III's foreign kinsmen. Henry himself was no great lover of tournaments and frequently prohibited them, while Simon de Montfort was obliged to cancel a tourney between his sons and Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Simon took action to prevent the friction with Clare blowing up into a full-scale row, inevitable if the bloodshed got out of hand.

The tourney at Chalon was a strange affair. English chroniclers made much of it, though it seems they relied on garbled reports. Walter of Guisborough identifies Edward's opponent as the 'Count of Chalon', but this title was in abeyance. The last count of Chalon, Jean, had exchanged his title in 1237 with the duke of Burgundy for the very rich seigneury of Salins. Jean's family retained Chalon as a surname, but his successors were not counts. Edward's opponent was most likely one of Jean's sons, either Pierre le Bouvier (“the Oxherd”) or his younger half-brother Jean, seigneur de Chalon. Since the chroniclers specifically reference Chalon, Jean is perhaps the more credible.

The 'count' is said to have invited Edward to tourney in his land. This sounded like an honourable invitation, but really he planned to capture the king and despoil his knights. To that end many men from all parts of Franche-Comté were summoned to the tourney, including great numbers of horse and foot. Before the event, the Burgundians bartered English horses and arms for sale and took to drinking to celebrate the plunder they would take.

Edward in turn summoned nobles from England to join him. When the day came, there were supposedly a thousand men-at-arms and footsoldiers on the English side, and twice that number on the other. Both sides lined up on a flat even field (think the Battle of Stirling No-Bridge in Braveheart) and charged. This was not generally how real battles were fought: tourneys were much like the popular Hollywood notion of medieval battles, with hundreds of men all mixed up together, hacking and slashing and generally behaving like maniacs.

The count sent forward his infantry first. Edward had a number of slingers and archers, who killed a great number of these men and chased them to the city gates. They were pursued all the way to the river, where many drowned. This means the tourney had already spilled off the field, broken the barriers and presumably torn through the spectators.

Then the mounted divisions or 'conrois' of knights charged each other. The count went for Edward at the head of fifty chosen knights – just as Edward had picked a death-squad to kill Simon de Montfort at Evesham – and attacked the royal conroi. Both men came together in the press and exchanged blows. When the count saw he could not overcome Edward with the sword, he threw away his blade and seized the king by the neck. Edward shouted:

“What are you trying to do? Do you think you can take me?”

To which the count replied:

“Most assuredly. I will have you and your horse.”

After this manly banter, Edward struck the count's horse, which reared and almost threw its rider. The count clung onto Edward's neck, but was beaten to the ground. At this point Edward left the field to catch his breath. When he saw how the Burgundians were treating the tourney as a real battle, he gave an order that might have come straight from the mouth of Don Corleone:

“Spare no-one you set eyes on now, and do the same to them as they are doing to us.”

Things now got a bit tasty. The English infantry, who had returned from their pursuit, set about the Burgundian knights; the horses were gutted and their girths cut, so their riders fell to the ground, where they could be polished off with a knife through the slits of their helms. Edward returned to the fray and attacked the count, who had been lifted onto a spare horse. At last the count begged for mercy, but in his fury the king refused to accept his surrender. Instead he was forced to yield to a mere knight.

Meanwhile the surviving Burgundians either surrendered or fled the field. After a few minutes of extra time the referee blew the whistle: no need for penalties, thank God.

Published on July 17, 2021 04:14

John the Little

On 12 December 1319 the king's justices at York were presented with a complaint by Simon of Wakefield that in December 1318 criminal gang had broken his houses and coffers at Hornington, west Yorkshire, and carried off his livestock, goods and cash.

On 12 December 1319 the king's justices at York were presented with a complaint by Simon of Wakefield that in December 1318 criminal gang had broken his houses and coffers at Hornington, west Yorkshire, and carried off his livestock, goods and cash. This offence was committed by a large number of men (see attached), including Simon Ward and his brothers and several of the Bradburns. The leader of the Bradburns, referred to elsewhere as 'Master' John Bradburn, was the nephew of Sir Henry Bradburn of Derbyshire, who was drawn and hanged after the battle of Boroughbridge in March 1322. Henry's younger brother Roger and his sons avoided this dreadful fate, and were granted charters of pardon in April. Roger had his late brother's lands restored to him in 1327.

Master John and his brothers formed part of the vast system of gentrified gangsters that virtually ran the Midlands and northern England in the latter years of Edward II and early reign of Edward III. They were frequently found in the company of James Coterel and Eustace Folville, as the various gangs combined or split off into small groups to raid and pillage and extort money.

The Hornington raid of December 1318 was the first recorded offence of the so-called Bradburn gang. They and their associates mainly operated in Derbyshire and Notts, and used the forests of the High Peak and Sherwood as a refuge. For instance, on 18 December 1330 a royal knight, Sir Roger Wennesley, was ordered to hunt down the Coterels, the Folvilles and the Bradburns and imprison them at Nottingham castle. Wennesley was chosen because he was a sworn enemy of the Coterels: he had committed several crimes himself and killed Laurence Coterel, one of James's brothers, by stabbing him in the guts with a dagger.

Interestingly, one of John Bradburn's followers at the Hornington raid was a John the Little or Little John of Leicestershire.

Published on July 17, 2021 01:44

July 16, 2021

Undermining Clare

In May 1269, at the ford of Rhyd Chwima, the Lord Edward agreed to Prince Llywelyn's request to obtain the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd. Maredudd was a nobleman of south Wales, lord of the commote of Machen in the lordship of Gwynllwg, the commotes of Edeglion and Llebenydd in the lordship of Caerleon, and the commote of Hirfryn in Ystrad Tywi.

In May 1269, at the ford of Rhyd Chwima, the Lord Edward agreed to Prince Llywelyn's request to obtain the homage and fealty of Maredudd ap Gruffudd. Maredudd was a nobleman of south Wales, lord of the commote of Machen in the lordship of Gwynllwg, the commotes of Edeglion and Llebenydd in the lordship of Caerleon, and the commote of Hirfryn in Ystrad Tywi.Although Maredudd was descended of the old princes of Deheubarth, he had not inherited Hirfryn. After the death of his grandfather, Maredudd ap Rhys ap Gruffudd, in 1201, other members of the lineage had seized the patrimony. Maredudd's father, Gruffudd, clawed back lands in Glamorgan by marrying Gwerfal, daughter of Morgan ap Hywel. Hirfryn had come into the possession of Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg, a descendant of the Lord Rhys, but sometime after 1257 it was transferred to Maredudd ap Gruffudd. Evidence is lacking, but it is probable that Prince Llywelyn confiscated the land after Maredudd defected to the English, and gave it to the descendant of the man whose ancestor had lost it in 1201.

The status of Maredudd ap Gruffudd was therefore key to Llywelyn's hopes of controlling this part of Wales. He needed to persuade the king that Maredudd was a Welsh baron, and a tenant-in-chief of the Prince of Wales i.e. himself. Thus he should rightfully hold his lands of Llywelyn.

King Henry had transferred the ongoing dispute between Llywelyn and Gilbert de Clare to Edward. This meant that Maredudd had to kneel before the English prince at Rhyd Chwima and swear that he, like his ancestors, would hold his lands according to the custom of Wales. Edward in turn allowed Maredudd to become a tenant-in-chief of Llywelyn, who owed his homage to the king.

In acceding to Llywelyn's wishes, Edward revoked Clare's lordship over Maredudd, and undermined the earl's recent conquests in Glamorgan. The commote of Gwyllwg in particular had been part of the Clare inheritance for centuries, while the recent wars had been Earl Gilbert establish control over Caerleon as well. Edward had also set a precedent for Llywelyn's desire to recover the homage of Gruffudd ap Rhys of Senghennydd, who was now languishing in Clare's dungeon at Kilkenny.

Clare's fury at Edward's decision sparked a major diplomatic row: Earl Richard of Cornwall, the king's brother, was obliged to step in to arbitrate, and the conflict on the March was discussed by envoys of Louis IX of France on their visit to the English court in autumn 1269. The quarrel between Edward and Clare threatened to wreck the prince's expedition to the Holy Land, and to plunge England into a second civil war. These grave potential consequences were spelled out by the bishops of Canterbury, who threatened to excommunicate either party if they broke the peace.

Published on July 16, 2021 04:01

July 15, 2021

Rhyd Chwima

In autumn 1268 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Gilbert de Clare came to a new understanding. This was after the dissolution of their pact in the previous year , whereby Llywelyn seems to have agreed to halt his military operations in Glamorgan while the earl marched east to capture London.

In autumn 1268 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Gilbert de Clare came to a new understanding. This was after the dissolution of their pact in the previous year , whereby Llywelyn seems to have agreed to halt his military operations in Glamorgan while the earl marched east to capture London.The transcript of this second agreement survives and is printed inside the Littere Wallie, edited by JG Edwards. It is dated 27 September 1268 and described as an agreement between the Prince of Wales and the Earl of Gloucester for the purpose of settling their differences. Up to that point nothing had been accomplished in this vein, despite Henry III's offer to Llywelyn that he might prosecute Clare 'coram rege' – that is, before the royal justices of King's Bench at Westminster.

Neither Clare or Llywelyn wanted to appear at Westminster. From the earl's perspective, that would mean surrendering March privilege to the authority of the crown; for Llywelyn, it meant enforcing his subordinate status as the king's vassal. Both wished to remain as independent of royal authority as possible, without actually rejecting Henry's overlordship. Since their legal status as earl and prince rested on the feudal supremacy of the crown, this was an exceptionally difficult tightrope to walk. One serious wobble could bring the whole edifice crashing down about their ears.

So, on the aforementioned date, Clare met Llywelyn at Pontymynaich inside Cantref Selyf. They agreed to remit their dispute to a board of arbitrators, four from each side, a form of negotiation that was typical of March custom. These men would meet in the new year and hold talks day by day until an agreement was reached in accordance with justice. If these talks failed, Clare and Llywelyn would seek another form of judgement. Only then, if that didn't work, would they agree to come before King's Bench. Meantime Clare would continue to hold the commote of Senghenydd Is Caech, while Llywelyn held Senghenydd Uwch Caech and the northern part of Meisgyn.

Henry continued to monitor the situation. When it became obvious that Clare and Llywelyn were using March custom as a means of stalling, the king transferred their dispute to his heir, the Lord Edward. Given Edward's general reputation, it might be thought that this was a hard-line measure, designed to whip the parties to heel. That would be simplistic and incorrect: this was grown-up politics, and Edward's job was to reach a sensible understanding. If he was not fit for the task, his father would have chosen other representatives.

Llywelyn, for his part, fully appreciated this. Both he and Clare agreed to submit to the prince's award, and in May 1269 he met Edward in person at the ford of Rhyd Chwima. Their discussions were encouraging; afterwards Llywelyn sent an unusually cordial letter to the king, expressing his satisfaction at the meeting with Edward. Anxious to maintain the general air of bonhomie, Henry invited Llywelyn to witness the translation of the body of Edward the Confessor to its shrine in the great church of Westminster, a project close to the king's heart.

At this stage, therefore, there was nothing inevitable about the dire fate that would overtake Llywelyn and his principality in just a few years. This in turn shows the dangers of reading history backwards and indulging in hindsight over context:

“The civility of the exchanges of the summer of 1269 suggest that there was, at that stage, a prospect that perseverance and good faith on the part of the prince and the heir to the throne would enable them to resolve the difficult problems confronting them. There was some reason for hope that the two nations might yet be brought to the continuing accord that the papal legate had held in prospect when peace had been made two years before.”

- J Beverley Smith: Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales

Published on July 15, 2021 04:20

July 14, 2021

Mighty castles

Towards the end of 1267 the brief pact between Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Gilbert de Clare dissolved. Llywelyn petitioned the king, Henry III, and levied a number of charges against Clare: the principal allegation was that the earl had occupied and held the patrimony of the prince's barons in Elfael Is Mynydd. The barons were named as Owain, Maredudd and Ifor, sons of Owain ap Maredudd, and Clare said to have taken their lands to the injury of king and prince.

Towards the end of 1267 the brief pact between Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Gilbert de Clare dissolved. Llywelyn petitioned the king, Henry III, and levied a number of charges against Clare: the principal allegation was that the earl had occupied and held the patrimony of the prince's barons in Elfael Is Mynydd. The barons were named as Owain, Maredudd and Ifor, sons of Owain ap Maredudd, and Clare said to have taken their lands to the injury of king and prince. The legal status of Elfael Is Mynydd is uncertain. Llywelyn clearly believed that the homage of the barons belonged to him as Prince of Wales. However, it was not among the lordships granted to Llywelyn at Montgomery in September 1267, and Henry regarded it as the inheritance of Roger de Tony, a Marcher baron. After Tony's death in 1264 it had been taken into royal custody, so it is difficult to see how Llywelyn could have laid claim. Later still, after the treaty of Aberconwy in 1277, it was alleged that he had seized the land to the exclusion of Tony's heir.

Llywelyn followed up by advancing his own interpretation of the treaty of Montgomery, and claimed that the homage of Gruffudd ap Rhys, a lord of Senghenydd and one of the Welsh barons of Wales, belonged to his principality. Prior to his alliance with Llywelyn, Clare had captured Gruffudd and packed him off to prison in Ireland. In response to his former ally's petition, the earl urged the king to restore territories in Glamorgan unjustly occupied by force and retained by force.

Henry had only just recovered control of London, recently occupied by Clare and his allies in England. This possibly influenced him to take a dim view of Clare's plea, even though he had granted the earl licence to conquer land in Wales in the previous autumn. In his response to prince and earl, Henry ventured no opinion but recommended that both submit their differences to negotiation, via the custom of the March.

The king was boxing clever. He sent separate letters to Clare and Llywelyn, and to the latter he raised another possibility. Since Gruffudd ap Rhys of Senghenydd was of the Englishry – 'de Anglescheria nostra' – Llywelyn could, if he wished, bring an action against Clare to the court of King's Bench (coram rege) at Westminster.

Clare, for his part, was unwilling to submit to March custom or the law of Westminster. He had, in his view, taken direct action within his own jurisdiction, and was not obliged to answer to any external power, even the king. In April 1268, in defiance of all, he started work on the mighty castle of Caerphilly.

Published on July 14, 2021 08:05

Gentleman savages

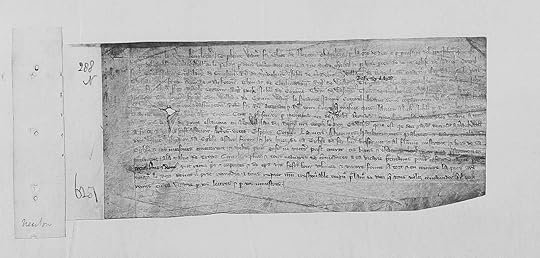

A petition from Walter de Newton, chaplain, dated c.1331 and complaining of attacks on Newton by James Coterel and his gang. This 'horrible trespass', as it is described, can be cross-referenced with an entry in the Patent Rolls, dated 12 October 1331; this more detailed entry alleges that Walter, vicar of the church of Bakewell in Derbyshire, was attacked by Coterel and at least 26 accomplices, who also carried away his goods.

A petition from Walter de Newton, chaplain, dated c.1331 and complaining of attacks on Newton by James Coterel and his gang. This 'horrible trespass', as it is described, can be cross-referenced with an entry in the Patent Rolls, dated 12 October 1331; this more detailed entry alleges that Walter, vicar of the church of Bakewell in Derbyshire, was attacked by Coterel and at least 26 accomplices, who also carried away his goods. This is one of the last allegations of violence against James Coterel. In the summer of 1331 he and his gang were involved in a murder, a maiming and a kidnapping, as well as the assault upon Walter de Newton. However, from the autumn of that year James started to eschew violence, apparently because it was bad for business. The use of force led to feuds against other outlaw gangs and diminishing financial returns, so instead he switched to blackmail and threats of violence to extract money.

The policy of extortion was adopted by the other gentry gangs north of the river Trent, and was done in a systematic and professional manner. For instance, in 1332 the mayor of Nottingham was 'asked' to send £20 to the 'societies of gentleman savages' – 'societatis de gentz sauvages'. This money was to be sent via Henry Wynkeburn, an official receiver employed by Coterel and other outlaw leaders. The sum was to be paid at Nottingham to a man bearing an indented bill, one part of which had come to the mayor with the letter. If he did not pay up, everything he owned outside the town would be burnt.

James Coterel was just one of many Mafia bosses operating in the midlands and northern counties towards the end of the reign of Edward II into the early years of Edward III. They were organised, highly competent and virtually immune from the law, since the majority of royal justices and bailiffs were in their pocket. Despite his prolific outlaw career, spanning almost a decade, James was only 'attached' – a writ dispatched for his arrest – on one occasion, and that came to nothing.

The successive governments of Edward II, Mortimer and Isabella and Edward III lacked both the will and the capacity to stamp out the outlaw gangs. Thus the only logical alternative was to make use of them. As one example, the Folville gang in Leicestershire were hired by Mortimer and Isabella to hunt down the fugitive Edward II and Hugh Despenser in South Wales.

When the young Edward III came to the throne, he or his advisors decided to channel the violent energies of the gangs against the enemies of the kingdom. James Coterel and Eustace Folville, among others, were employed as commissioners of array in Scotland and France, and – irony of ironies – rewarded with lucrative posts as local justices and bailiffs. Set a thief to catch a thief, indeed.

This policy was not without its risks. One of James Coterel's brothers, Nicholas, was appointed Queen Philippa's bailiff of the High Peak and a captain of sixty archers dispatched to serve in Scotland. He promptly embezzled money from the collection of the parliamentary subsidy at Bakewell, and then stole the wages of the soldiers under his command. Accused of these and many other crimes, he 'stealthily withdrew' and vanished from sight.

Published on July 14, 2021 05:51

July 12, 2021

Assault on Dover

On 11 July 1265, the vigil of Saint Benedict of Nursia, Countess Eleanor de Montfort fed twenty-five paupers in one day. This took place at Dover castle, where Eleanor awaited news of the war raging on the Welsh marches and the fate of her husband, Earl Simon.

On 11 July 1265, the vigil of Saint Benedict of Nursia, Countess Eleanor de Montfort fed twenty-five paupers in one day. This took place at Dover castle, where Eleanor awaited news of the war raging on the Welsh marches and the fate of her husband, Earl Simon.The feeding of paupers on saint's days was standard, but Eleanor appears to have been conducting a public relations exercise for her husband's regime, especially among local sympathisers. Just before she arrived at Dover, she entertained the burgesses of the Montfortian town of Winchelsea to dinner; in mid-June she entertained the burgesses of Sandwich, and the burgesses of both towns in July.

En route from Porchester to Dover, Eleanor was accompanied by Montfortian supporters. These included Sir William de Munchensy, Sir Ingram Balliol and Sir Robert de Bruce, later known as the Competitor and grandfather of King Robert I of Scotland. For some reason Balliol and Bruce departed from Eleanor's company when she reached Wilmington priory in Sussex, only for Bruce to rejoin her at Dover between June and August.

Eleanor's deliberate courting of the Cinque Ports (Winchelsea, Sandwich, Rye, Hastings and Deal) paid off. After her husband's death at Evesham, the burgesses of Winchelsea and Sandwich remained loyal to the Montfortian cause and preyed on commercial shipping in the Channel. They were just as motivated by piracy as politics, and the attacks were not confined to English merchant ships. Two merchants of Winchelsea, John Sampson and Thomas le Lung, plundered a town off the coast of Brittany and sailed off with 121 tuns of wine valued at 600 marks. Elsewhere a Spanish ship carrying 105 tuns of wine was seized off Dieppe, while Scottish merchants of Berwick were plundered of goods worth 320 marks. And so on.

The rebel garrison at Dover was also making its presence felt. Eleanor's household roll lists payments to men riding out to steal cattle 'de praeda' or 'from plunder' instead of 'de stauro' or 'from stock'. These raids occurred over several days between 23-26 August.

Dover was clearly a problem for the royalists, but in late October they were handed an unexpected opportunity to retake it. The castle was being used to hold forty royalist prisoners, who hatched a plot with two of their gaolers to overcome the garrison. Sometime before 26 October they went into action, and managed to seize the keep and hold the doors fast while a messenger was smuggled out. He rode hell for leather to London to inform the king, Henry III, who dispatched the Lord Edward and a troop of men-at-arms to storm the castle.

Edward and his men rode 'without sleep until they arrived at the castle and assailed it'. While his soldiers scaled the walls, the men inside the keep broke into the storeroom and captured the stock of crossbows. Caught between a sudden hail of crossbow bolts from the keep, and the assault of Edward's men, the garrison agreed to surrender on terms.

Published on July 12, 2021 04:20

July 11, 2021

Dung and worms

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Courtrai, remembered as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, in Flanders in 1302. As Fiona Watson said in her recent book on Robert de Bruce, Courtrai is the most important battle nobody ever talks about. It certainly flies under the radar compared to Falkirk, Bannockburn, Crécy etc.

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Courtrai, remembered as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, in Flanders in 1302. As Fiona Watson said in her recent book on Robert de Bruce, Courtrai is the most important battle nobody ever talks about. It certainly flies under the radar compared to Falkirk, Bannockburn, Crécy etc. The political situation immediately prior to the battle was complex. In 1294 Philip IV of France had triggered war with England by breaking an oath to Edmund of Lancaster, Edward I's younger brother, and annexing the duchy of Gascony. This in turn caused Edward to renounce his homage to Philip and declare war on France. Both sides recruited a vast coalition of allies that included most of the princes of Western Europe. In 1295 Philip signed a treaty with the Scots, in which the latter appeared as a third party in Philip's main alliance with King Erik of Norway against Edward of England and the Holy Roman Emperor, Adolf of Nassau. Count Guy of Flanders also allied with the English after renouncing his homage to Philip.

The result was a messy stalemate. Edward managed to recover part of Gascony, but his Flanders expedition was abortive and ended in a truce in October 1297. Adolf of Nassau sent some military aid to the English, but failed to come in person and was killed in battle by the Duke of Austria, Philip's ally, on 2 July 1298. A few weeks later Edward defeated the Scots at Falkirk, which enabled him to recover control of south-east Scotland. Philip's focus was on Flanders and Gascony, and he used the Scots as leverage to distract the English: for instance, he renewed the truce with Edward at Provins only a few weeks before his Scottish allies were defeated at Falkirk.

The truce in Flanders was only temporary. Edward's diplomats had failed to persuade the pope, Boniface VIII, to include the Flemings in a permanent peace between England and France. In his response to their plea, Boniface declared he would risk nothing for the sake of Flanders alone. Edward thus broke his previous marriage contract with Count Guy and entered into a new alliance with France, cutting the Flemings adrift.

As part of the compromise, Philip restored Ponthieu to the English, which he had confiscated along with Gascony in 1294. This meant that Edward was once again Philip's vassal, and could be summoned to do military service in the French army.

Things now get seriously complicated. In early 1302 Edward was obliged to agree to the Treaty of Asnieres, whereby he agreed to let Philip have custody of all the lands and castles the English had conquered in south-west Scotland in the previous year. This exposed the weakness of Edward's position, though he continued to munition his existing garrisons in Scotland.

Edward may have calculated that Philip would do unto the Scots as he had done unto the English in Gascony. To take custody of the lands in question, the French had to send men to Scotland by 16 February 1302. That date came and went without a Frenchman in sight, which made the treaty null and void. Philip had broken his word, again, and Edward was able to secure his gains of the previous summer.

Philip had switched his attention back to Flanders. The truce of 1297 had expired 1300, enabling his forces to overrun the county and capture Count Guy and his family. Philip's conquest proved no more secure than Edward's initial occupation of Scotland, and in the spring there was serious unrest at Bruges. Philip wanted to summon Edward to serve against the Flemings, which may explain why he failed to deliver on the terms of the Scottish treaty. The summons was certainly dispatched: Edward was ordered to come to Arras with his men-at-arms, prepared and ready to campaign in Flanders.

The English king is known to have sent at least one of his barons of Ponthieu, Jean de Varenne, to fulfil the obligation. Then, in May 1302, the Flemings rose up and slaughtered every Frenchman they could find at Bruges. This massacre was remembered as the Matins of Bruges (or Brugse Metten in Dutch).

To quell the revolt, Philip sent an army under Robert of Artois into Flanders. Artois had previously defeated the English at Bellegarde and the Flemings at Bullskamp, and was obviously expected to make short work of the Flemish urban militia.

The result was a shattering Flemish victory, in which Artois and a swathe of French nobles were slaughtered along with hundreds of knights and men-at-arms. This wasn't the first time an army of footsoldiers had defeated mounted chivalry in battle: Stirling Bridge in 1297 is one previous example. All the same, it was totally unexpected and sent shockwaves throughout Europe. The Annals of Ghent concluded:

“And so, by the disposition of God who orders all things, the art of war, the flower of knighthood, with horses and chargers of the finest, fell before weavers, fullers and the common folk and foot soldiers of Flanders, albeit strong, manly, well armed, courageous and under expert leaders. The beauty and strength of that great [French] army was turned into a dung-pit, and the [glory] of the French made dung and worms.”

The disaster of Courtrai forced Philip to perform a U-turn. He was now obliged to throw everything at Flanders, and could no longer afford to be at loggerheads with Edward. In early 1303 he started negotiations to restore Gascony to the English, albeit under the same feudal arrangement as before. Philip also cut ties with the Scots, just as Edward had abandoned the Flemings, ending a decade-long war with England that had achieved nothing and emptied the coffers of both kingdoms

Published on July 11, 2021 05:40