David Pilling's Blog, page 18

September 27, 2021

No easy options

It's random record Monday. Below is a payment from April 1283 for soldiers going from Castell y Bere to Harlech:

It's random record Monday. Below is a payment from April 1283 for soldiers going from Castell y Bere to Harlech:Otto de Grandison

Item, payment to lord Otto de Grandison for the sustenance of 560 foot-soldiers going with him from the castle of Bere to Harlech, £20 by tally.

Sum - £35 11s 8d.

Otto or Othon Grandison was one of the many Savoyards in the service of Edward I. What he found at Harlech is a hot potato – or lukewarm by this stage, since recent research appears to have fizzled out. It seems there was a Welsh castle on the site, and the Edwardian stronghold was built on top of it.

While Othon went off to Harlech, the siege of Bere continued. The royal army was led by Roger Lestrange, William de Valence, Rhys ap Maredudd and the sons of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn. Most of the soldiers were Welsh, as in:

Cardigan

Item, payment to Eynon ap David, for 39 foot-soldiers from Cardigan for the aforesaid days of Friday and Saturday, 13s.

Emlyn [and] Coedrath

Item, payment to David Vachan, for 200 foot-soldiers from Emlyn and Coedrath, for the aforesaid 5 days, £8 6s 8d.

And so on. So far as Rhys and Gruffudd, this war was the last act in the ancient grudge-match between the rival dynasties of Dinefwr, Mathrafal and Aberffraw. When the castle of Bere fell, bribed into surrender, the lions of Gwynedd were torn down and replaced with the lion rampant of Powys Wenwynwyn. The defenders, as per the normal custom of medieval warfare, were allowed to walk away.

Among them was the poet, Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Goch. He had much to chew on: in 1277 he had taken a fee of £20 to desert Prince Llywelyn and join the royal army. Five years later, he composed Llywelyn's magnificent elegy. There were no easy options.

Published on September 27, 2021 04:12

September 25, 2021

Urban communes

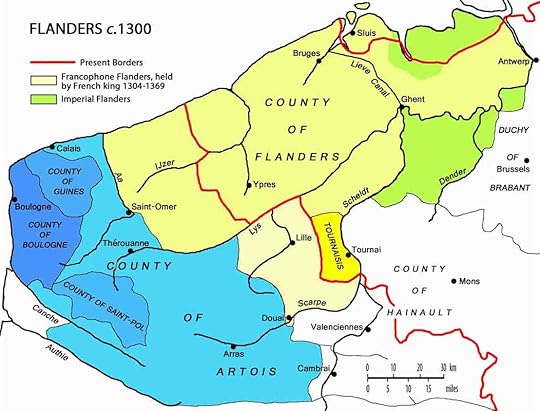

Flanders, autumn 1297. There is an interesting gap in Edward I's correspondence between 19 September-1 October. Prior to the 19th, while based at Ghent, the king had exchanged regular correspondence with the regency council in London.

Flanders, autumn 1297. There is an interesting gap in Edward I's correspondence between 19 September-1 October. Prior to the 19th, while based at Ghent, the king had exchanged regular correspondence with the regency council in London. The break in the record is somewhat mysterious. The king was holed up in the city, along with his allies the Count Guy of Flanders and the Duke of Brabant. Their enemy Philip the Fair, meanwhile, was at Ingelmunster, some 30 miles to the south-west. Here the French king received the keys of Bruges, handed over by the Flemish citizenry.

Flanders was bitterly divided between Flemish loyalists and a pro-French faction, called 'Laelierts' or 'the party of the Lily'. Guy's efforts to defend his land was undercut by the defection of so many Flemish knights, and the arrival of reinforcements from England and Brabant were not enough to fill the gap. The allies could only sit tight at Ghent and stare at the German border, waiting for imperial troops to show up.

Unfortunately for them, King Adolf was being chased around his own territory by pro-French elements inside the empire. They were led by the Duke of Austria, Albert of Hapsburg, called the One-Eyed for reasons that should be obvious. To do him justice, Adolf had sent as much support as he could to Flanders, but was unlikely to make a personal appearance.

The result was an awkward stalemate. Philip would not advance from Ingelmunster. The allies would not advance from Ghent. Nobody in their right mind wanted to risk another Bouvines. Screw that for a game of soldiers.

Edward kept himself busy. He knighted Count Guy's sons and the Duke of Brabant, and agreed to arbitrate between Guy and envoys from Flemish cities. These men represented the growing urban communes inside Flanders, who have become wealthy enough to govern their own affairs. If Guy wanted to be their lord again, he would have to make concessions. He was not a popular figure, and it appears the envoys refused to speak to him directly. Instead – a common theme of his reign – Edward was invited to step in.

Published on September 25, 2021 04:07

September 24, 2021

Old spindle-shanks

The recent volume Edward I: New Interpretations, has been reviewed by M.P. Guthrie of Lancaster University in the new issue of The Mortimer History Society. Guthrie's conclusion is interesting:

The recent volume Edward I: New Interpretations, has been reviewed by M.P. Guthrie of Lancaster University in the new issue of The Mortimer History Society. Guthrie's conclusion is interesting:“When viewed collectively, King and Spencer [the editors] have successfully continued to shift Edward away from the binate classifications which often linger over monarchical histories. In this respect, readers are drawn into research avenues that can inform our understanding of Edward's character and explore possible misaslignments in the scholarly debates. In this last respect, King's chapter is sure to encourage lively academic debate in the coming years. The general consensus put forward in this edition further propel Edward I on the upward trajectory of academic opinion, firmly placing him as a king who met the contemporary expectations of his office and which will add to Edward's enduring celebrity among English kings.”

In other words, the general opinion on Edward is swinging back to the position he occupied in the first half of the 20th century, before a bunch of nationalists, movie-makers and a particular clutch of 1960s revisionist academics got their claws into him. One of the chief movers among the latter was a young Michael Prestwich, who painted a very unflattering picture of the king in his early works. Prestwich later revised his opinion, not that anyone in the popular sphere noticed. By that point we had all swallowed a good dose of Edith Pargeter, Sharon Penman and Braveheart, and Edward's reputation had plunged to the lowest depths of Hell. His old enemy Simon de Montfort junior, condemned to roast forever in a lake of boiling blood in said establishment, probably had a good chuckle.

None of which is to pretend that Edward, a tough king who over-reached himself in Scotland, is in any way beyond criticism. For instance, the New Interpretations volume contains an excellent piece by Michael Brown, highlighting the king's failure to reconcile the Scottish nobility. Nor did the older generation of historians, Powicke and Tout et al, ever pretend otherwise. In the end, whatever particular drum one chooses to beat, old spindle-shanks will always be of interest:

“Whether he has been regarded with opprobrium or admirations – or a mixture of both – he commands our ongoing interest and attention, as the contributors of this present volume demonstrate.”

Published on September 24, 2021 04:35

September 23, 2021

The Castilian affair

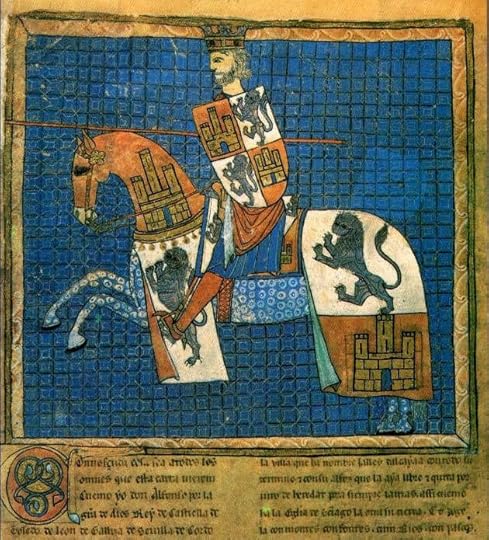

In autumn 1282 Gaston de Moncada, Viscomte of Béarn, led 41 Gascon knights and 59 men-at-arms across the Pyrenees to aid Alfonso X, King of Castile. Alfonso was at war with his second son, Sancho, over the succession: the king wished his grandsons by his deceased eldest son, Ferdinand, to inherit the crown. Sancho refused to be pushed aside and gathered support among the Castilian nobility.

In autumn 1282 Gaston de Moncada, Viscomte of Béarn, led 41 Gascon knights and 59 men-at-arms across the Pyrenees to aid Alfonso X, King of Castile. Alfonso was at war with his second son, Sancho, over the succession: the king wished his grandsons by his deceased eldest son, Ferdinand, to inherit the crown. Sancho refused to be pushed aside and gathered support among the Castilian nobility.Alfonso officially declared Sancho a rebel and parricide, and asked Rome for help. The pope in turn issued letters to the kings of England and France, ordering them to send troops to assist the King of Castile.

This was the context of Gaston being sent over the mountains by Edward I. The viscount had originally been summoned to fight in Wales, but suggested to the king he could do more useful service in Castile. For one thing, it was a lot closer: Béarn lay on the northern edge of the Pyrenees, only a hop and a skip away.

Edward may not have been terribly enthused, even though Alfonso was his brother-in-law. Back in 1266 the Castilian king had intrigued with Theobald of Navarre to exploit civil war in England and invade Bigorre, an English-held province on the edge of the Pyrenees. How much Henry III and his heir knew of Alfonso's involvement is uncertain. What is known is that Theobald bribed an English monk to write a false history of Charlemagne, for the purpose of justifying his claims to Bigorre.

Gaston was far more more eager for this task, since he had a grudge against the Infante Sancho. Back in 1270 Sancho had severed his betrothal to one of Gaston's daughters, and married the daughter of another nobleman. Resentment over this breach of contract lingered in the South: one of Sancho's chief supporters, the lord of Biscay, also deserted the Infante's cause and went back to King Alfonso. He was apparently motivated by news of Gaston's arrival at Alfonso's court.

Even so, the war didn't go especially well for the king. His wife and other sons all threw their support behind Sancho, as did the King of Portugal. Meanwhile the assembly of the estates of the realm declared Alfonso unfit to wield power: he was formally deprived of the powers of monarchy, namely, justice, taxation and the right to hold castles, though he was left with the empty title of 'King'.

Alfonso did, however, retain the loyalty of most of Andalusia and Murcia. In a desperate bid to regain control, he recruited the support of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub, the Muslim emir of the Benmerines. Together they launched a joint invasion of Castile, but were unable to dislodge Sancho from Córdoba. Afterwards the emir withdrew to Morocco.

Gaston's role in all this is unclear. He later claimed compensation from Edward for loss of horses: as ever, it is impossible to know if the Dobbins met their end in battle, or were served up for dinner, or did not, in fact, die at all. The civil war itself continued to rage for several years, but quite frankly the chronicle accounts are totally confusing and I want a sandwich.

Published on September 23, 2021 07:42

September 22, 2021

The dung-named

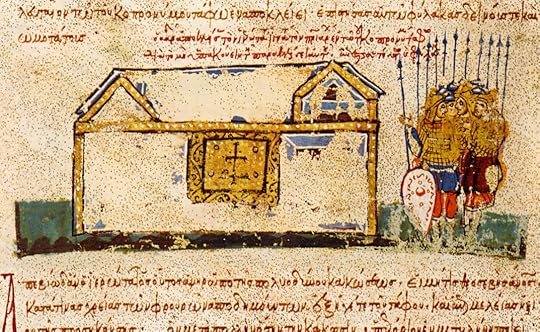

A depiction of Byzantine soldiers at the tomb of Constantine V (reigned 741-775), another of the fascinating eastern emperors. Constantine was an Iconoclast, which triggered a revolt among the Roman clergy. His response was brutal in the extreme: a number of clergymen were executed or tortured to death, while others were forced to marry nuns in the Hippodrome, in public mockery of their vows.

A depiction of Byzantine soldiers at the tomb of Constantine V (reigned 741-775), another of the fascinating eastern emperors. Constantine was an Iconoclast, which triggered a revolt among the Roman clergy. His response was brutal in the extreme: a number of clergymen were executed or tortured to death, while others were forced to marry nuns in the Hippodrome, in public mockery of their vows. This savagery aside, Constantine was one of the more successful emperors. He defeated the Bulgarians to the west, and exploited a civil war among the Arabs to recover lost Roman territory to the east. In this latter conflict he adopted a form of 'colonialism' by forcing groups of Christians to resettle in the reconquered territories. The emperor's reputation was such that, in 775, an Arab army retreated at the mere mention of his name.

His legacy is, unsurprisingly, mixed. Orthodox histiorians referred to Constantine as Kopronymos, meaning 'the dung-named', along with epithets such as 'a precursor to Antichrist', 'a monster athirst for blood', 'an unclean and bloodstained magician taking pleasure in evoking demons', and so forth.

The Byzantine army, however, remembered him as a hero. After a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Pliska in 811, Byzantine soldiers broke open Constantine's tomb and begged him to lead them again. Some interesting parallels with Arthur, another military hero who was also demonised by early Christian writers.

Published on September 22, 2021 04:33

September 21, 2021

Lions of Gascony

In September 1282 Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham, granted a subsidy to certain towns in the duchy of Gascony; specifically Bordeaux, Bourg, Libourne, Saint-Emilion, Saint-Macaire, Langon, La Réole, Bazas, Saint-Sever and Dax. The precise amount of the grant is unknown, but it was a payment for troops to be raised from these places and sent to crush the revolt of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and his brother Dafydd in North Wales.

In September 1282 Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham, granted a subsidy to certain towns in the duchy of Gascony; specifically Bordeaux, Bourg, Libourne, Saint-Emilion, Saint-Macaire, Langon, La Réole, Bazas, Saint-Sever and Dax. The precise amount of the grant is unknown, but it was a payment for troops to be raised from these places and sent to crush the revolt of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and his brother Dafydd in North Wales.The rebellion in Wales caught Edward I completely by surprise. In one sense it gave him a handy excuse not to travel to France to join his aunt, Margaret of Provence, and the league of French barons she had assembled to conquer Provence from Charles of Anjou. Margaret's response to her nephew's letter of excuse was somewhat frosty, but the scale of the uprising in Wales could scarcely be denied.

The records of the Gascon expedition are almost 100% intact. In April a royal clerk, Pons Amat, was dispatched to Gascony to raise troops and victuals for the army in Wales. He first engaged Jean de Grailly, a Savoyard and former seneschal of Gascony, to raise 40 crossbows and 12 sergeants. These men were paid advance wages by the constable of Bordeaux. Pons then paid a sum of £438 6 shillings 8 pence for supplies: 420 quarters of wheat and as many oats, 16 quarters of beans, 105 flitches of bacon in barrels, 100 tuns of wine. Again this was all paid for by the revenues of Bordeaux.

As J Trabut-Cussac remarked - “Ce ne fut pas l'unique contribution de la Gascogne a la guerre de Galles.” The nobles who contracted to serve with their retinues included Guitard de Bourg, the sire de Gironde, Elie de Caupenne, Arnaud de Gaveston, Assins de Navailles, Pierre de Grailly, the Vicomte de Tartas, Auger de Mauléon, Guillaume de Rions, Amanieu d'Albret, Arnaud Guillaume de Montravel and many more.

This might read like a meaningless list of weird Gascon names, but the point is they were the fighting elite of the duchy. At the same time as the Welsh expedition, another company of Gascon knights went over the Pyrenees, led by Gaston de Béarn, to assist Edward's brother-in-law Alfonso X to fight his own son, Sancho.

The Gascon troops in Wales were deployed on Anglesey and east of the Conwy from November 1282-February 1283. They appear to have been used as the spearhead of the final royal advance into Gwynedd from December 1282, shortly after the death of Prince Llywelyn. One Gascon nobleman was killed in the fighting, along with 9 mounted crossbowmen and 25 infantry. A handful of sick and wounded men were shipped home. Casualty figures among the Welsh are unknown, but winter war in the mountains must have been a grim, bitter affair. Chronicle accounts give some idea of the carnage:

“They, the Gascons, remain with the king, receive his gifts,

In moors and mountains they clamber like lions.

They go with the English, burn down the houses,

Throw down the castles, slay the wretches;

They have passed the Marches, and entered into Snowdon.”

It should be noted these men were not 'mercenaries' in the typical sense of foreign hirelings. Edward was himself French by outlook and ancestry, albeit born in England: not just French, moreover, but a man of the South. The Gascons were his vassals, bound to do him military service in the same way as his subjects in England, Ireland and Ponthieu (and, for that matter, Wales).

Published on September 21, 2021 05:51

September 20, 2021

Impossible strains

Charles Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, on Edward I's administration of Gascony:

Charles Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, on Edward I's administration of Gascony:“The vast domains of the King of England were controlled with consummate skill; the officers of Edward, Jean de Grailly and Luke de Tany, seneschals of Gascony, Thomas of Sandwich, seneschal of Ponthieu, Master Bonet of Saint-Quentin, in charge in 1285 of the administrative reform of the duchy, Raymond de la Ferrier, were indeed men filled with zeal and merit. They left much more testimony of their activity than the bailiffs and seneschals of France.”

Langlois referred to the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris (1259), whereby the Plantagenet kings renounced most of their lands on the continent in exchange for the duchy of Gascony. This would now be held as a fiefdom of the Capets, which in turn meant that one crowned head was now both the equal and inferior of another.

The situation was awkward, to put it mildly. Langlois describes the early reign of Edward I as a sort of 'cold war': a fragile outward peace was maintained, whilst at the same time the agents of both kingdoms vigorously shafted each other.

This is shown in the secret correspondence of Edward's agents. Unfortunately much of this material is badly indexed and untranslated, and Langlois died before he could get to grips with it. He did translate some letters, such as the following from February 1279. This is from King Edward to his seneschal, Jean de Grailly:

“You informed me that the King of France orders that the fouage, conceded to us by our men of Gascony, would be raised for his account and the account of the Viscountess of Limoges. If perchance someone raises this fouage in the name of the King, answer him with the softness and courtesy which are appropriate that you cannot allow him to act, unless they exhibit royal letters which formally enjoin you to do it. If, by chance, he is carrying similar letters, answer that because of bad harvests and mortality of the cattle, we extended by one year or two a lifting of the tax. And we send letters of extension to you, one for a year, the other for two years; you will please show them.”

The issue here is that Philip III, king of France, had levied a fouage or hearth-tax on the men of Gascony. This was technically illegal, since Philip had no direct authority and the Gascons had already conceded the tax to Edward. But he did it anyway, simply because he could. Feudal overlords everywhere rode roughshod over the rights of their vassals. That was the deal.

Edward resorted to a subterfuge. The seneschal was to prevent Philip's officers collecting the tax, unless they were carrying royal letters. If they were, the seneschal was to show letters from Edward, showing that the king-duke had lifted the tax for one or two years.

Thus, Edward did not oppose Philip's unlawful right to impose a tax. He did, however, dare the French king to oppose Edward's right to postpone the tax, on the grounds of bad harvests. If Philip had gone so far, it was a different matter. In that case he would have denied Edward's right to govern the duchy at all, which was a clear breach of feudal contract. The result could only be war.

Philip III was not so inclined: he liked to push boundaries, just to see what he could get away with, but not break them. The crisis passed, but every year the strain of this impossible relationship got a little heavier...

Published on September 20, 2021 01:16

September 19, 2021

Perfection at Poitiers

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Poiters in 1356, another of the extraordinary run of English military successes during the reign of Edward III.

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Poiters in 1356, another of the extraordinary run of English military successes during the reign of Edward III. There is little point getting all revisionist about it, or pretending that Edward and his captains have been overrated. It was a remarkable period and that's flat. My own focus is the thirteenth century, from which I know how incredibly difficult it was to score any kind of military success against the might of Capetian France.

Until the advent of Edward III, the best that can be said is that the Plantagenets clung onto Gascony by their fingernails and kept the French out of England. This was only achieved at a cost that puts their efforts within the British Isles in the shade: Edward I, for instance, spent a million pounds in four years fighting the French. That is almost three times the sum total of his expenditure in Wales over thirty years, including the famous castles.

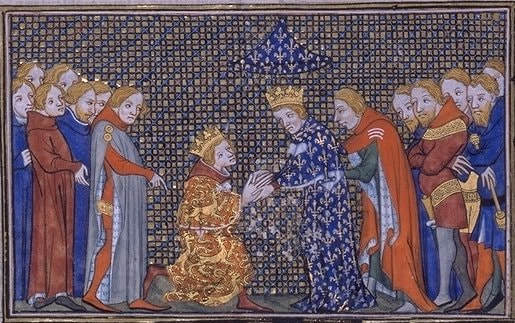

So, here is the king of France surrendering to the English at Poitiers. I can think of no higher honour than rendering the scene in Lego.

Published on September 19, 2021 04:19

September 18, 2021

Old alliances

On 18 September 1297, at Ghent in Flanders, Edward I issued a privy seal warrant for the council in London to release payments to two of his allies, Adolf of Nassau and the Duke of Brabant. This was to be done as speedily as possible, lest the king's honour and the 'business' of the war – et nostre busoigne – should be endangered.

On 18 September 1297, at Ghent in Flanders, Edward I issued a privy seal warrant for the council in London to release payments to two of his allies, Adolf of Nassau and the Duke of Brabant. This was to be done as speedily as possible, lest the king's honour and the 'business' of the war – et nostre busoigne – should be endangered.The actions of Duke John II of Brabant, one of Edward's son-in-laws, are another obscure feature of this war. As current research at the University of Antwerp has shown, the duke was an important player.

John had arrived at Ghent to join the king, and brought a large number of Brabancon knights with him:

'The Duke of Brabant was also there

with many men, as you should know

from his land, and also with many

from the borders of the Meuse.'

Lodewijk van Velthem

The Meuse in this context was the Maas, a collection of lands beyond the Maas river; they included the duchy of Limburg (won for Brabant in 1288), Valkenburg, Rodulc and Dalhelm, known as 'Outremeuse' or Overmaas territories i.e. beyond the Maas river.

These knights of the Maas who came to Flanders included Waleran von Valkenburg or Fauqemont. Along with his fellows, Waleran was bound to serve against the French via a complex system of obligations. He was a vassal of the Duke of Brabant, and had contracted to serve Edward I for a fee of 350 livres tournois. In addition, he held land or 'fief-rents' of at least five other lords, including Count Guy of Flanders.

This made Waleran the equivalent of a pluralist – a clergyman holding several benefices – and put him in all kinds of difficult situations. In 1285 he took part in a great tournament against the Duke of Brabant's father, John I. Perhaps to avoid recognition, he fought under the nickname of 'Le Roux'. He was captured and had to be ransomed by Count Guy.

Waleran's descendents would also fight for the English, although it ended badly. In 1337 Edward III retained his grandson, Thierry, and a company of 100 men-at-arms at a very large fee of 1200 florins per annum for life. He was also to be given another sum of 12,000 florins in two instalments, plus wages for war. These were extremely generous terms: for good measure, Edward promised to pay Thierry's ransom if he was captured, and compensation for loss of horses.

Unfortunately, in 1340 Edward's system of finance collapsed, which left him unable to pay outstanding debts. Thierry wrote a string of angry letters to the king, who in turn blamed his clerks in England for failing to raise the sum in wool or cash. In addition, Edward claimed, his officials had behaved rudely towards Thierry and sent him 'curt and unpleasant' answers. Despite the royal wrath, the lord of Valkenburg never got his money, and the old alliance was severed.

Published on September 18, 2021 06:28

September 16, 2021

True longbows

In mid-September 1297 Edward I was forced to make a hasty exit from Bruges in Flanders: he had been tipped off that the citizens intended to surrender the city to the French. They also planned to take him and his men prisoner into the bargain. The haste of the army's departure is shown by the large amount of supplies left behind; this included thousands of quarters of wheat as well as meat carcasses, beans, peas and oats.

In mid-September 1297 Edward I was forced to make a hasty exit from Bruges in Flanders: he had been tipped off that the citizens intended to surrender the city to the French. They also planned to take him and his men prisoner into the bargain. The haste of the army's departure is shown by the large amount of supplies left behind; this included thousands of quarters of wheat as well as meat carcasses, beans, peas and oats.Edward and his ally, Count Guy Dampierre, hurried towards the refuge of Ghent. This was a large walled city, surrounded by moats and ditches, one of the few left in the hands of Flemish loyalists. On the way they were tracked by the French knights of Philip the Fair.

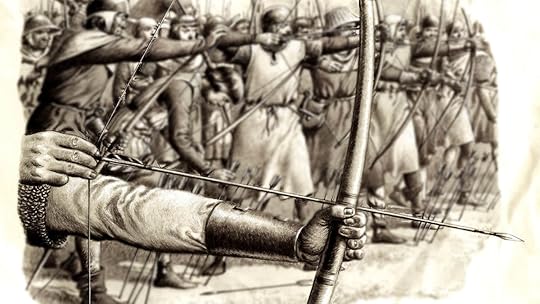

According to Walter of Guisborough, the French refused to attack the allied army in the open because Edward had so many archers in his host. Quote:

“...for they feared the footsoldiers of the English king because there were many archers amongst them.”

At this stage, before reinforcements were shipped over later in the month, Edward's infantry consisted of the following:

Glamorgan: 898

West Wales: 1,789

Barons' lands: 640

North Wales: 1,963

Welsh March and England: 923

Total: 6,123

As you can see, the majority were Welsh. Most of these Welsh footsoldiers are described in the accounts as archers; with the exception of the men of Snowdon and Caernarfon under Gruffydd Llwyd, who are simply described as 'infantry'. There was also one small company of 21 crossbowmen raised in West Wales.

Unless there was something special about these archers, it is difficult to see why armoured French knights and men-at-arms refused to attack them. Light infantry with no armour, carrying ordinary bows, would have been trampled into the Flemish mud.

The implication must be they were armed with 'longbows' or the war bow. This is supported by modern archaeological digs at castle sites in Wales, which have discovered hoards of narrow armour-piercing arrowheads. These heads are too long and heavy to have been fitted to short bows, the longest with socket (discovered at Dryslwyn) being over 18 centimetres in length.

Altogether this is enough to suggest that 'true longbows' were in use among the Welsh in this period. The earliest reference to a 'longbowe' in English apparently dates from 1383, over a century later.

Published on September 16, 2021 07:33