Impossible strains

Charles Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, on Edward I's administration of Gascony:

Charles Victor Langlois, a French medievalist, on Edward I's administration of Gascony:“The vast domains of the King of England were controlled with consummate skill; the officers of Edward, Jean de Grailly and Luke de Tany, seneschals of Gascony, Thomas of Sandwich, seneschal of Ponthieu, Master Bonet of Saint-Quentin, in charge in 1285 of the administrative reform of the duchy, Raymond de la Ferrier, were indeed men filled with zeal and merit. They left much more testimony of their activity than the bailiffs and seneschals of France.”

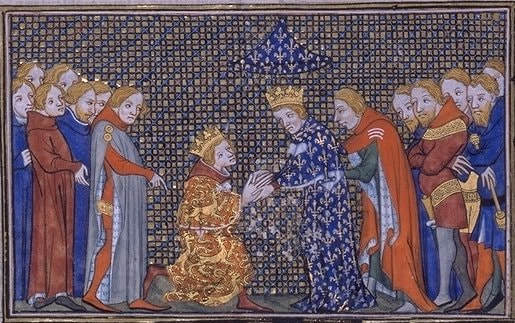

Langlois referred to the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris (1259), whereby the Plantagenet kings renounced most of their lands on the continent in exchange for the duchy of Gascony. This would now be held as a fiefdom of the Capets, which in turn meant that one crowned head was now both the equal and inferior of another.

The situation was awkward, to put it mildly. Langlois describes the early reign of Edward I as a sort of 'cold war': a fragile outward peace was maintained, whilst at the same time the agents of both kingdoms vigorously shafted each other.

This is shown in the secret correspondence of Edward's agents. Unfortunately much of this material is badly indexed and untranslated, and Langlois died before he could get to grips with it. He did translate some letters, such as the following from February 1279. This is from King Edward to his seneschal, Jean de Grailly:

“You informed me that the King of France orders that the fouage, conceded to us by our men of Gascony, would be raised for his account and the account of the Viscountess of Limoges. If perchance someone raises this fouage in the name of the King, answer him with the softness and courtesy which are appropriate that you cannot allow him to act, unless they exhibit royal letters which formally enjoin you to do it. If, by chance, he is carrying similar letters, answer that because of bad harvests and mortality of the cattle, we extended by one year or two a lifting of the tax. And we send letters of extension to you, one for a year, the other for two years; you will please show them.”

The issue here is that Philip III, king of France, had levied a fouage or hearth-tax on the men of Gascony. This was technically illegal, since Philip had no direct authority and the Gascons had already conceded the tax to Edward. But he did it anyway, simply because he could. Feudal overlords everywhere rode roughshod over the rights of their vassals. That was the deal.

Edward resorted to a subterfuge. The seneschal was to prevent Philip's officers collecting the tax, unless they were carrying royal letters. If they were, the seneschal was to show letters from Edward, showing that the king-duke had lifted the tax for one or two years.

Thus, Edward did not oppose Philip's unlawful right to impose a tax. He did, however, dare the French king to oppose Edward's right to postpone the tax, on the grounds of bad harvests. If Philip had gone so far, it was a different matter. In that case he would have denied Edward's right to govern the duchy at all, which was a clear breach of feudal contract. The result could only be war.

Philip III was not so inclined: he liked to push boundaries, just to see what he could get away with, but not break them. The crisis passed, but every year the strain of this impossible relationship got a little heavier...

Published on September 20, 2021 01:16

No comments have been added yet.