David Pilling's Blog, page 20

August 9, 2021

Fraternal division

Above is a pic of my recent visit to the castle of Dinas Brân in Denbighshire, once part of the medieval lordship of Powys Fadog.

Above is a pic of my recent visit to the castle of Dinas Brân in Denbighshire, once part of the medieval lordship of Powys Fadog. Gruffudd of Bromfield, ruler of Powys Fadog, died in 1269. He left four sons, who gathered at Dinas Brân in 1270 to confirm their late father's grants to their mother, Emma. This confirmation was ratified by the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.

Now he was ruler of the principality, Llywelyn meant to enforce his authority. Anyone who thought his title was purely nominal could think again. Shortly after the meeting at Dinas Brân, Llywelyn intervened again in northern Powys to divide the land between the brothers. He chose to favour one, Madog, who was also his brother-in-law. Madog was granted the lands of Madog Maelog Gymraeg and Maelor Saesneg along with half of Glyndyfrdwy, while his brothers got lands elsewhere. Not enough, to judge from their reaction.

The castle of Dinas Brân was central to this awkward arrangement. It stood in the northern fringes of Nanheudwy, inside lands that formed the share of Llywelyn Fychan, one of Madog's brothers. When their father built the castle in the 1260s, it stood as a symbol of the unity of northern Powys. Now it was a symbol of division. In an effort to please everyone, Prince Llywelyn allowed Madog to retain possession of the castle, so long as Llywelyn Fychan could occupy part of it. This arrangement was similar to power-shares in English Gascony, where the sheer number of gentry and lack of castles meant property often had to be shared. That didn't mean the gentry liked it: one Gascon nobleman blocked up the windows of his tower, so he didn't have to look at his brother in the hall below.

When war broke out in 1276, the brothers were among the first to defect to Edward I. The first to do so was Llywelyn Fychan, who was received into the king's peace in December. The terms of his submission are revealing. In the event of a reconciliation between prince and king, Llywelyn Fychan's homage would be retained by Edward and his heirs, and not restored to Prince Llywelyn. This in turn meant that Llywelyn Fychan's lands would no longer form part of the principality of Wales.

In the spring of 1277 the king's commanders marched from Chester into Powys Fadog. These were Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Earl William de Beauchamp and Peter de Montfort. Prince Llywelyn's favourite, Madog, bowed to military reality and went over to the king. The terms of his submission are even more revealing. Madog was obliged to accept that the castle of Dinas Brân, once captured by Edward's forces, could be demolished at the king's will.

This in turn meant the castle was still offering resistance, even after Madog and Llywelyn Fychan had agreed to surrender it. The likelihood is that Prince Llywelyn had gone further than his original settlement, and planted a Venedotian garrison inside Dinas Brân. Thus, none of the lords of Powys Fadog got to enjoy their father's castle, which partially explains their hostility towards the prince.

Published on August 09, 2021 01:31

August 1, 2021

Come out, ye traitors!

1 August 1265. Simon de Montfort the younger has sacked Winchester and marched his army to Kenilworth in Warwickshire. Here, in the shadow of the mighty castle, his men pitch camp. They put off their armour and relax in the taverns, baths and stews of the town.

1 August 1265. Simon de Montfort the younger has sacked Winchester and marched his army to Kenilworth in Warwickshire. Here, in the shadow of the mighty castle, his men pitch camp. They put off their armour and relax in the taverns, baths and stews of the town.Simon has a plan. He knows the Lord Edward is at Worcester, roughly halfway between Kenilworth and Earl Simon's army at Hereford. If Edward should ride out to attack Simon senior, Simon junior will attack Edward in the rear. Thus, the prince will be crushed in a pincer movement. Possibly. Maybe.

First, however, his men are in need of a hot bath. According to the Chronicle of Melrose, this is actually a motive for them leaving the safety of the castle:

“Their object in leaving the castle was this, that when they rose from their beds early in the morning, they might have the comfort of a satisfactory bath.”

Well, everyone enjoys a good soak. Although maybe not on campaign, with one's enemy within striking distance. What Simon doesn't know is that Edward has planted two spies in his camp. One is Margoth, a woman disguised as a common soldier, and the other a knight named Ralph of Arden. These two feed information to Edward at Worcester, informing him the Montfortians at Kenilworth are wide open to attack.

The prince must knock out one of the Simons before they can link up. For obvious reasons, he chooses to go for Simon junior. On 1 or 2 August (the chronicles are uncertain), he sets off eastward at night via an indirect route to Kenilworth. Then he doubles back and makes a detour towards Bridgenorth and Shrewsbury. This is apparently done to confuse any Montfortian spies in his ranks.

Edward takes as many men as possible. Some of his footsoldiers are loaded into carts so they can keep up with the mounted knights and men-at-arms:

“Dusk approaching, mounted in wagons, if flying across the full width of the county, coming to Kenilworth as dawn arose.” (Wykes)

Margoth meets Edward outside the town and guides his men into a valley. There they put on their arms. Suddenly they hear the sound of wheels approaching. Fearing betrayal, the royalists quickly mount up and advance, lances in hand, only to meet some harmless supply wagons.

They press on through the dawn and fall upon the sleeping camp. The sleeping Montfortians, dreaming of hot baths and rubber ducks, are jerked awake by a terrifying war-cry:

“Get up, get up, rise from your beds and come out, ye traitors! You are the followers of that deep-dyed renegade, Simon, and by the death of God, you are all dead men!”

Simon's men scatter in all directions, like autumn leaves in a gust of wind. Some run off entirely naked, others hide in alleyways or dive into the cellars of houses; others flee carrying bundles of clothes, abandoning their horses and armour. Simon himself, with the minimum of dignity, flees stark naked from his pavilion and dives into the moat (or a boat, according to other sources). He manages to get across and into the castle before the royalists can grab him.

Meanwhile the Montfortian camp is thoroughly pillaged, and a large number of prisoners taken. These include twenty bannerets, among them Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford, Baldwin Wake, William de Munchensy, Richard de Gray and Hugh Neville. Adam Newmarket, who had been captured at the battle of Northampton, is made prisoner a second time. Rotten luck, old boy. So much rich baggage and so many horses are taken, that even the pages or foot-boys of Edward's knights ride back to Worcester in triumph on captured steeds. The captives are packed off to Gloucester.

Simon senior, unaware of the disaster at Kenilworth, has left Hereford and made a dart for the Severn. Thanks to Edward's absence, he is finally able to get across the river and marches to Kempsey. This is only a few miles south of Edward's base at Worcester, but both sides are too exhausted to force a battle. Instead Simon slips away at night and turns north, hoping to join the remainder of his son's battered host. Together they still have enough men to overwhelm Edward and his allies.

Edward isn't going to sit on his backside and allow that to happen. After a short rest for his men, he leaves Worcester and gives chase. The hunt is on.

Published on August 01, 2021 04:15

July 31, 2021

Last stand at Tegh

Among the few members of the notorious Folville gang to ever suffer for his crimes was Richard, a younger brother of the gang boss, Eustace. Richard Folville was a clergyman, the rector of Tegh in Rutland, but his godliness didn't stop him 'riding wi' ma gangers' (as they said on the Scottish border, where the term 'gang' apparently comes from).

Among the few members of the notorious Folville gang to ever suffer for his crimes was Richard, a younger brother of the gang boss, Eustace. Richard Folville was a clergyman, the rector of Tegh in Rutland, but his godliness didn't stop him 'riding wi' ma gangers' (as they said on the Scottish border, where the term 'gang' apparently comes from). Richard was indicted with his brothers in many of their crimes. Apart from their most famous exploits, the murder of Roger Belers and kidnapping of Richard Willoughby, he also took part in lesser deeds. For instance, at dawn 'of a certain day' in 1327 the Folville brothers robbed one Walran de Baston of a cask of wine in the fields of Uffington in Oxfordshire. Earlier, on 12 October 1326, Richard and his siblings robbed a priest, Robert Cort, of two horses and harnesses belonging to him worth £20.

And so on. Despite his offences, Richard was rector at Tegh for twenty years: possibly, like the baby-eating Bishop of Bath & Wells in Blackadder, his flock were completely unaware of his criminal activities. So far as they were concerned, his only flaw was a quick tipple before Evensong. Or, as is more likely, everyone knew exactly what a rogue he was, and were too frightened to do anything about it. When ELG Stones wrote his classic essay on the Folvilles in 1956, he uncovered evidence that the gang had friends in very high places. These included Mortimer and Isabella and even Richard Willoughby, whom the Folvilles had kidnapped and humiliated. He evidently got over it – money can soothe most bruised egos – and was a member of the panel of justices that acquitted the gang of all crimes.

Even so, justice was not entirely blind. In early 1341 the keeper of the peace in Rutland, Sir Robert Colville, decided he could no longer endure Richard Folville's presence at Tegh. He accused Richard of homicide, theft and other crimes and took an armed posse to the church to arrest him.

There followed a dramatic Ned Kelly-style last stand. When the posse approached, Richard seized a bow and arrows and shot at them as they passed through the cemetery. One man was shot dead and several others wounded. Richard and his servants than fled inside the church and barricaded the doors. When the under-sheriff shouted at them to come out, they refused. At this a crowd of local men arrived to help the posse, and together they broke down the doors and dragged Richard outside. His head was hacked off in the street. This was outright murder, but Colville knew what he was doing. If Richard went to trial, as he had many times, he would be acquitted by his friends among the judiciary.

Colville's action placed the authorities in an awkward position. He had slain a notorious felon, but in doing so bypassed the law. If he was brought to trial, it might lead to a public scandal: here was the only officer who had taken effective action against the Folvilles, being persecuted for doing his job.

The solution was to spare Colville and his men, but impose a penance. The calendar of the register of papal letters, which contains details of Richard's death, notes that:

“The knight [Colville] and his followers are to go barefooted, naked except their breeches, with rod in hand, and halters round their necks, if they safely can, round all the principal churches of the district, and while a penitential psalm is recited at the doors of each church, are to be beaten with the rod, confessing their crime, and are to be declared deprived of whatever patronage they had in the church, after which they are to be absolved, and have a penance enjoined.

Published on July 31, 2021 01:43

July 30, 2021

Super-Simons

July 1265. Simon de Montfort junior, called Bran in the Sharon Penman novels to distinguish him from his father, is laying siege to Pevensey castle in Sussex. On 28 June he had been granted the custody of Surrey and Sussex, responsible for keeping the peace in those counties. In practice this means reducing the stubborn royalist garrison at Pevensey, which has held out for over a year against Earl Simon's forces.

July 1265. Simon de Montfort junior, called Bran in the Sharon Penman novels to distinguish him from his father, is laying siege to Pevensey castle in Sussex. On 28 June he had been granted the custody of Surrey and Sussex, responsible for keeping the peace in those counties. In practice this means reducing the stubborn royalist garrison at Pevensey, which has held out for over a year against Earl Simon's forces.The siege, like all military operations, is expensive. On 24 November 1264 the Bishop of Winchester was ordered to pay over 700 marks (about £500) from the surplus of a fine due to the Crown, towards the expenses of the siege at Pevensey. Simon junior gives a quittance for 300 marks of this sum at Winchester on 16 July 1265. Thus, money raised from a fine meant to be paid to the king is redirected towards fighting the king's loyal supporters.

A talented soldier, Simon junior is in need of all the romantic gloss later fiction writers will pour over him. He is grasping and self-seeking, and once pursued Isabella de Forz all the way into the Welsh marches, so he could force her to marry him and get his hands on her inheritance. This unsavoury episode, and the antics of Simon's brothers, do little to endear the Montfort clan to the English public. According to Robert of Gloucester, a certain knight once confronted Earl Simon and warned him to restrain his sons:

“For thou has wicked sons, foolish and unwise; you do not reprove their deeds, nor will you at all chastise them. I warn you to give good heed, and correct them soon; you may be blamed for them, for vengeance is a granted boon.”

Other chroniclers were unimpressed with Simon's efforts at Pevensey. Thomas Wykes derided the siege as 'useless and worthless', while the more moderate Oseney chronicle says 'he [Simon] spent much effort, but made little or no progress'. Certainly, the castle is a tough nut to crack. The ancient Roman walls are in good repair, and supplemented with a Norman keep and gatehouse. Due to its position on the coast, Pevensey is also easily supplied by sea. This deprives Simon of the besieger's best weapon, hunger.

At the end of June Earl Simon, stranded beyond the Severn by the Lord Edward and Gilbert de Clare, sent messengers to summon help from his son. They were intercepted, but at least one made it through to Pevensey. Upon receiving the news, Simon junior breaks up the siege and summons the barons to London. There he raises an army of between 16 to 20 bannerets and an 'infinite' number of fighting men.

Simon marches from London into Hampshire and on 14 or 16 July reaches Winchester, Henry III's birthplace. The inhabitants bar the gates against an army not led by the king. Instead of moving on, Simon decides to plunder the city. Some of his men clamber through a window into the monastery of St Swithin's, adjoining the city wall, and smash the doors open. The rest of his men pour into the streets and set about helping themselves: private houses and churches are plundered, while the Jews in particular are targeted. Winchester is picked clean, and the Montfortians come away with 'an infinity of money'.

The sack of Winchester, however profitable, is an exercise in time-wasting. Perhaps Simon junior is not yet aware of the destruction of his father's transport ships in the Bristol Channel. With the Montfortian fleet at the bottom of the sea, Earl Simon has no means of getting over the Severn and linking up with his son.

Once he does learn of the disaster, Simon junior can only push on or 'keep buggering on', as Churchill once said. He takes his army to the family castle at Kenilworth, a massive stronghold in the heart of Warwickshire, equipped with all modern siege defences. Time to relax. After a long and anxious march, Simon's men decide to kick back a little:

“And having dined, and given tired horses their feed, with little forethought or precaution, fearing nobody, taking off the arms of war, because they thought themselves in safety, they slept on camp beds until morning.” (Wykes)

Young Simon's approach has not gone unnoticed. His arrival has forced the Lord Edward to return to his base at Worcester. His army is now roughly equidistant between the forces of the two Simons at Hereford and Kenilworth (24 and 34 miles respectively). He has a straight choice: sit tight and let his enemies converge, or knock out one of the Simons before they can merge into a great big super-Simon. Of the two, Simon junior is the easier prey.

Published on July 30, 2021 05:02

July 29, 2021

A dish of oysters

In which Henry V resolves a dispute while eating oysters:

In which Henry V resolves a dispute while eating oysters:“In the first year of his reign there were two knights at great debate: one was a Lancastrian, the other, a Yorkshireman and they each built up as strong a force as they could and skirmished together; and men were killed or injured on both sides. And when the king heard about it, he sent for them: and they came to see the king at Windsor just as he was going to dinner; and once he was informed that they had arrived, he commanded them to come before him. And then he asked them whose men they were. His liegemen, they replied. 'And whose men are they that you have raised to fight for your quarrel?' His men, they answered. 'And what authority or mandate had you to raise up my men or my people to fight and kill each other as part of your quarrel? In doing this you deserve to die.'

And they could not excuse themselves, but besought the king for his grace. And then the king said by the faith that is owed to God and to St George, unless they agreed and accorded by the time he had eaten his oysters they would both be hanged before he supped. And then they went away and agreed between themselves and returned when the king had eaten his oysters. And then king said 'Sirs, how do things stand between you?' And then they knelt down and said, 'If it please your good grace we are agreed and accorded.'

Etc. This story is from the late 15th century Tomlynson Brut Chronicle. It is probably apocryphal, but the interesting feature of these anecdotes is they were meant to reflect a known feature of the king's personality. So, whether or not the tale is true, it appears Henry V could show a light touch in dealing with legal matters. The chronicler might have also intended to draw a comparison between Henry's effective conciliation of warring parties in England, and the failures of his successors.

Published on July 29, 2021 04:03

July 28, 2021

The rule of law

Kingship and the rule of law (1)

Kingship and the rule of law (1)This is an episode from the chronicle of Matthew Paris, concerning the robbery of foreign merchants in the pass of Alton near Winchester in 1248. Paris puts a speech into the mouth of Henry III, meant to illustrate the king's personal concern for justice:

'The lord king therefore called a gathering of the bailiffs and free men of the same county, namely Hampshire. And said to them with a scowling look: “What is it that I hear concerning you? The complaint of the despoiled has reached me. Out of necessity I have come to investigate. There is no county or neighbourhood in the whole breadth of England so infamous or disgraced by such crimes. For when I am present, in the same city or suburbs or in adjoining places there have been robberies and homicides. Nor are these bad things all. Even my own wine exposed both to plunder and pillage is carried off by these malefactors, laughing and getting drunk as they go. Can such things be tolerated further? To eradicate this and like crimes, I have commissioned wise men to rule and guard my kingdom together with me. I am but one man; I do not want, nor am I able, to carry alone the entire burden of the whole kingdom without co-operation. I am ashamed and weary of the stench of this city and the adjacent area. I was born in this city, and never was such disgrace inflicted on me as here. It is probable, however, and believable and now fairly well apparent, that you citizens and compatriots are infamous accomplices and confederates. I will call together all the counties of England, so that they might detect your crimes, judging you as traitors to me, nor will guileful arguments profit you further.”

According to the editor, the speech is dramatic licence on Paris's part: Henry III was at Winchester during the sessions of the eyre rather than at the time of the robbery. Even so, the passage serves a purpose. It is meant to underline the limits of royal power, and show the monarch was reliant on the co-operation of his subjects in the upholding of law and order. Whether or not he actually spoke these words, the frankness and sense of exasperation of the speech is supposedly characteristic of Henry and offers a glimpse of the man behind the crown.

Published on July 28, 2021 00:32

July 25, 2021

A storm on the March

From volume V of the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris, under the year 1257:

From volume V of the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris, under the year 1257:“Then indeed at this time, from among the nobles who had recently come from Germany was James Audley. He was strong and rich, but had his lands, possessions and castles situated in the Marches of Wales. While he was absent the Welsh had hostilely invaded, burnt and expelled the people from his lands, and so he assisted the greatest number of them to the infernal regions, as the blood of his own kindred on the hands of the enemy required. But, while going round his marshy lands, he found many unsuspected Welsh hiding in their dens like foxes, where they could repel their enemies and then disembowelled the expensive horses in order to repulse their attack. In this manner James forced the enemy back and homes and castle fortified with men were reduced to burning ashes on both sides.”

This is typical Paris, lurid and overblown, but some useful details can be picked out. His description of Welsh guerilla warfare, springing from ambush to disembowel horses and bring the riders to ground, tallies with other accounts. For instance, chronicle accounts of the battle of Crug Mawr in 1136 explicitly describe Welsh soldiers cutting the hamstrings of Norman horses to disrupt their charge. This was apparently how the battle was won, even though modern internet sources (the source of all knowledge, naturally) describe the Welsh using longbows at the battle.

The account itself describes the ravaging of the lands of James Audley, whose main fortress was at Weston under Redcastle in Shropshire. It generally pays to look beyond the surface of chronicle accounts. Surviving court rolls show that Audley came to the Curia Regis (king's court) in November 1260 to complain of the following outrage:

He alleged that on 29 June Fulk Fitzwarin, John Lestrange and Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn had sent certain Welshmen, led by Gruffudd Sais and Gruffudd ab Owain, to attack Audley's vill at Forde. They burnt the vill and two others, killed eight men, fatally wounded ten more, and led away ten prisoners. The raiders also lifted a prey of 260 oxen and cows, 80 sheep and 57 horses. Fitz Warin and his allies were summoned to court, but (as was typical) failed to appear.

This was a fairly standard episode of March warfare. Audley's enemies took advantage of his absence in Germany to plunder his lands, and were apparently driven off when he came back. A few years later Audley allied with Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Hamo Lestrange to invade Chester, but were driven out by Earl Robert de Ferrers. Afterwards Audley was packed off by the king to take charge of Ireland, a bit like being sent to the Eastern Front in World War Two, or Afghanistan in the 19th century. Off you go, son: do great things, perhaps, and make sure you don't come back.

Nor did he. While fighting in a skirmish against the Irish, Audley fell off his horse and broke his neck. Swings and roundabouts.

Published on July 25, 2021 03:53

July 23, 2021

Gangs and lords

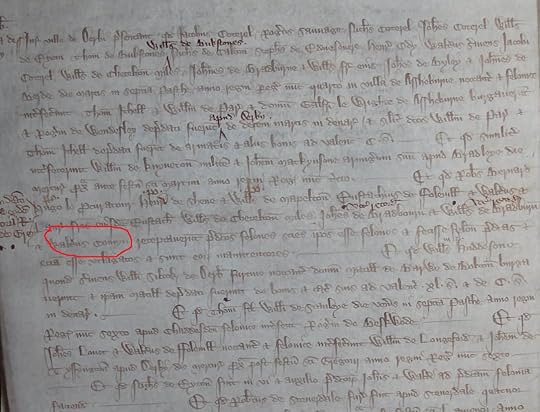

Attached is the first membrane of a commission set up in 1333 to deal with criminal gangs in England, principally the Coterels and Folvilles. I posted on this topic recently, but a few more details have emerged since.

Attached is the first membrane of a commission set up in 1333 to deal with criminal gangs in England, principally the Coterels and Folvilles. I posted on this topic recently, but a few more details have emerged since.Among those accused of aiding and abetting the outlaws is one Walter Comyn (circled in red on the image). This man seems to have been a kinsman of the main branch of Comyn of Badenoch, driven out of Scotland by Robert de Bruce after he murdered the head of the family, John, and John's uncle Robert Comyn at Greyfriars church in Dumfries in 1306.

Walter Comyn also appears in several documents relating to Scotland. In 1310 he was a prisoner of the Scots, implying he had chosen the English side (as many Comyns did), and was exchanged for Maria Bruce, whom Edward II had in custody. This was done at the request of Geoffrey Mowbray and Walter's other friends in England.

He next appears on 2 December 1331, when he was given protection so he could go overseas on the king's business with Henry Beaumont, heir to John Comyn of Badenoch. Over a year later, on August 1332, Edward III ordered Walter's outlawry to be suspended because he had surrendered and was now in prison at Wigmore castle in Hereford, pending trial.

Thus, sometime between these dates Walter Comyn chose to throw in his lot with the outlaw gangs of the midlands and northern counties. As it happens, we know exactly what he was getting up to. Another surviving court record, dated 14 February 1332, reads thus:

“And that James Coterel, Nicholas and John, his brothers, Robert Griseleve, Edmund and Roger his brothers, William Corbet of Tasley [Shropshire], Nicholas de Eton, John de Dinston of Walton [Derby], William de la Warde the younger, Robert son of Richard Foljambe, Nicholas de la Firde, Robert son of Matthew de Vyers, Nicholas de Sparham and Walter Comyn ride with armed force secretly and openly, and are maintainers and receivers of Ralph son of Geoffrey of Repton, Roger le Megre and Reginald de la Mere, notorious thieves, outlawed in that county, and that they received them at Dean Hollow in the second week of Lent, in the sixth year of the reign of King Edward III [c 15 March 1332].”

From this it appears the influence of the gangs was spreading into the borderlands and Welsh Marches. One of the gang, William Corbet of Tasley, sounds like a member of the powerful Corbet family of Gorddwr, Caus and Morton Corbet. The location of their activities also explains why Walter Comyn ended up in prison at Wigmore, a March stronghold.

Published on July 23, 2021 01:49

July 22, 2021

Age of Ambiguity

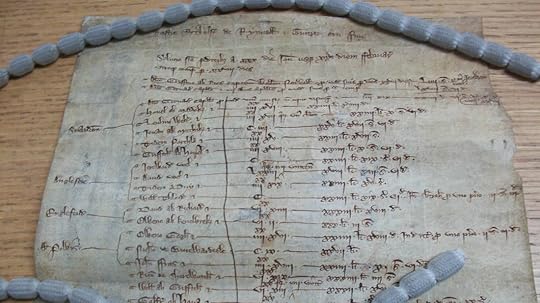

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Among the ten thousand Welshmen present at the battle was a certain Iorwerth Foel, a landholder of Anglesey, whose career was traced by the late A.D. Carr.

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Among the ten thousand Welshmen present at the battle was a certain Iorwerth Foel, a landholder of Anglesey, whose career was traced by the late A.D. Carr. Iorwerth was one of the gentry class in Wales who found a way to survive and prosper in the wake of the Edwardian conquest. He first appears in a petition to parliament dated 1278, where he claimed that Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had ravaged his lands and taken his goods and livestock on Anglesey. Further, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the prince.

These things were apparently done to punish Iorwerth for deserting the prince and joining the royal army in the war of 1276-77. He was one of many Welshmen to do so, and the causes of this sudden collapse of Llywelyn's authority are still not fully understood.

Iorwerth next appears in 1298, on a document I photographed at the National Archives last year (pic above). This is a muster roll for men of North Wales summoned to defend the northern counties of England after William Wallace's victory at Stirling Bridge in September 1297. Iorwerth appears on a list of centenars, mounted officers in charge of a hundred men, summoned to serve in February 1298. Edward I was in Zeeland at this point, and returned to England in March to begin counter-operations against Wallace.

The experience of the Welsh at Falkirk is a bit of a mystery. Walter of Guisborough, an English chronicle, described the Welsh troops rioting on the night before the battle, after getting drunk on wine brought to the English camp at Linlithgow by sea. Edward restored order by sending in his household knights, killing eighty Welshmen and several priests. Guisborough's tale may be doubted: the inventory for the supply ships happens to have survived, and shows the vessels had no alcohol on board. The muster rolls for the campaign, which survive almost entire, show no dramatic fall in numbers among the Welsh.

However, similar problems are also reported by Peter Langtoft and William of Rishanger. The latter wrote that one of the king's knights warned him not to trust the Welsh:

“King Edward, you are mistaken if you put your trust in the Welsh as you once did. Instead, take their lands from them.”

On the day of battle itself, according to Rishanger, the Welsh refused to fight until the Scottish spear-rings or schiltrons were broken. When it became clear the king was winning – and would be asking difficult questions afterwards – the Welsh suddenly rediscovered their enthusiasm:

“The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the land like snow in winter.”

Iorwerth's part in all this is unknown. He certainly survived the battle, and went on to greater things. In the following years he accumulated more land on Anglesey, until he was one of the wealthiest men on the isle. After a few more stints of military service in Scotland, he retired and died in 1333, quite old and very rich. Iorwerth was far from exceptional, and men like him cannot simply be stuffed under the carpet of history:

“Our thinking about how Wales developed in this period has thus to incorporate both the traditional tale of princely accomplishment, disaster at the hands of Edward I and subsequent colonial oppression, and a newer narrative of the contradictions inherent in achievement, widespread rejection of princely rule and significant accommodation to, and profit from, regime change. It was indeed an Age of Ambiguity.”

- David Stephenson

Published on July 22, 2021 00:43

July 20, 2021

War Wolf

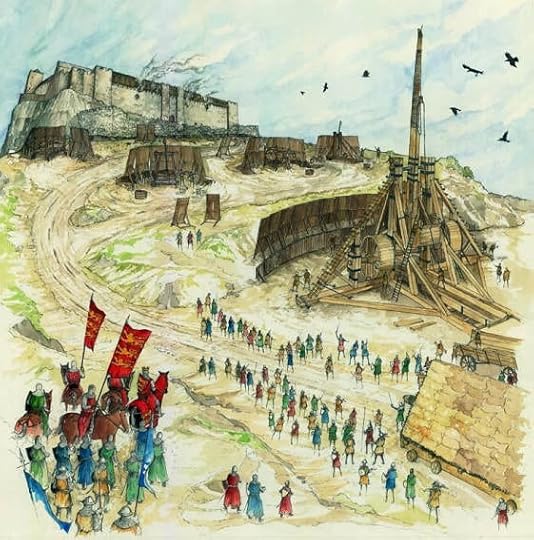

On 20 July 1304 the garrison of Stirling castle in Scotland offered their unconditional surrender to Edward I. Famously, the king refused because he wanted to try out his new toy, the monstrous trebuchet Loup de Guerre or Wolf of War/War-Wolf. Nobody was allowed to leave or enter the castle until it had lobbed a few rocks at the walls.

On 20 July 1304 the garrison of Stirling castle in Scotland offered their unconditional surrender to Edward I. Famously, the king refused because he wanted to try out his new toy, the monstrous trebuchet Loup de Guerre or Wolf of War/War-Wolf. Nobody was allowed to leave or enter the castle until it had lobbed a few rocks at the walls. This appears to have been a symbolic gesture as much as anything. None of the defenders were hurt, and the only casualty was an English turncoat who had conspired to surrender the castle to the Scots back in 1299. After the surrender, he was dragged off on a horse-drawn hurdle and hanged from the nearest tree.

There followed a typical bit of medieval siege theatre. The men of the garrison came before Edward as supplicants, barefoot and with ashes on their heads, to beg mercy. He replied “You don't deserve my grace, but must surrender to my will.” When they knelt before him, he turned away and started weeping. At this the defenders were spared and packed off to various prisons.

This wasn't the first time Edward had turned on the waterworks in public. He did so in the crisis of 1297, where he had confronted his chief critic, Robert Winchelsey, on a raised platform outside Westminster palace. Before an adoring crowd, the two men started crying and embraced each other in a show of reconciliation. What they might have whispered to each other in the throes of their loving cuddle is lost to history.

The siege of Stirling was pure theatre from start to finish. Edward was escorted to the castle by a troupe of female Scottish minstrels, who sang to him 'just as they had done in the time of King Alexander'. This was to emphasise the point that Edward's regime in Scotland was a natural transition from the reign of Alexander III; all that awkward business with John Balliol had been stuffed under the carpet. Balliol himself was in France and would die in 1314 – the year of Bannockburn, ironically – living on his nice family estates in Picardy. Poor chap.

The 'English' army at Stirling was partially Scottish. In March the king had held a parliament at St Andrews, the first Edward staged in Scotland since 1296. Here a total of 129 Scottish landowners swore homage to the king, which meant he could draw upon their service for the reduction of Stirling a few months later. Edward summoned the earls of Lennox, Menteith and Strathearn, along with Robert de Bruce, John Comyn of Badenoch and the sheriff of Stirling, Alexander Livingston. The latter was ordered to bring all the forces of his bailiwick, except the men of Lennox, implying their loyalty was suspected. The involvement of so many Scots in the king's army was another 'propaganda' device.

“This was reinforced, no doubt intentionally, by the parliament at St Andrews. The measures to be taken against all who continued to rebel were therefore approved by those members of the Scottish political community who were present at St Andrews. Even though the siege of Stirling was obviously a military operation, it seems to have been portrayed as a national effort in the interests of law and order.”

- Fiona Watson, Under the Hammer

In other words, Edward tried to present the siege as an internal police action rather than an act of invasion. He also arranged for a special window to be made so his young French queen, Margaret, and her ladies could watch the show from a safe distance.

During the siege the old king rode about under the walls wearing no armour, daring the Scottish defenders to shoot him. This was either a bit of chivalrous stupidity on Edward's part, or a deliberate effort to project an invincible warrior-king image. It almost ended badly: he was hit in the arm by an arrow, while another stuck in his saddle, and then a rock hurled from a springald broke his horse's spine and sent him tumbling. The king's guard had seen enough and dragged their master back to his pavilion, where he was made to sit quiet and stop being silly.

In all the siege lasted ninety days from 22 April-24 July. The constable of Stirling, Sir William Oliphant, had 120 men to defend the castle at the beginning. According to an English chronicle, the Flores, only fifty remained at the end. Apart from War-Wolf, fourteen siege engines were constructed and transported for the assault, and great piles of bows, arrows, crossbows and quarrels sent. Lead was taken from the churches near Perth and Dunblane to act as weights for the trebuchets, while a kind of flaming missile was also deployed. This is sometimes called 'Greek Fire', but it seems most unlikely that Edward had access to the mysterious Byzantine weapon. In reality it seems to have been a type of sulphur-based explosive, mixed by two specialist French engineers.

There was one attempt by a Scottish force, led by Sir William Wallace, to break the siege lines. Wallace had no support and was routed by Humphrey Bohun, the earl of Hereford. At last, exhausted and with no hope of relief, the garrison surrendered. This appears to have done the king's ageing libido a power of good: his last child, Eleanor, was conceived a couple of months later.

Published on July 20, 2021 04:08