Age of Ambiguity

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Among the ten thousand Welshmen present at the battle was a certain Iorwerth Foel, a landholder of Anglesey, whose career was traced by the late A.D. Carr.

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Among the ten thousand Welshmen present at the battle was a certain Iorwerth Foel, a landholder of Anglesey, whose career was traced by the late A.D. Carr. Iorwerth was one of the gentry class in Wales who found a way to survive and prosper in the wake of the Edwardian conquest. He first appears in a petition to parliament dated 1278, where he claimed that Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd had ravaged his lands and taken his goods and livestock on Anglesey. Further, he complained that he dared not and could not cultivate nor inhabit his hereditary lands nor approach any part of the land of the prince.

These things were apparently done to punish Iorwerth for deserting the prince and joining the royal army in the war of 1276-77. He was one of many Welshmen to do so, and the causes of this sudden collapse of Llywelyn's authority are still not fully understood.

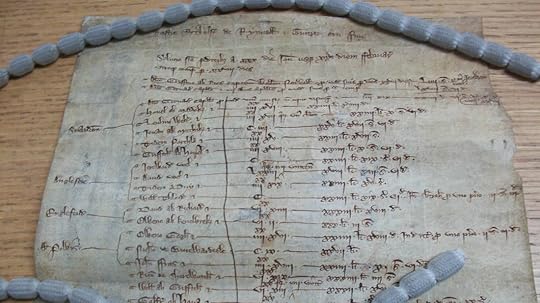

Iorwerth next appears in 1298, on a document I photographed at the National Archives last year (pic above). This is a muster roll for men of North Wales summoned to defend the northern counties of England after William Wallace's victory at Stirling Bridge in September 1297. Iorwerth appears on a list of centenars, mounted officers in charge of a hundred men, summoned to serve in February 1298. Edward I was in Zeeland at this point, and returned to England in March to begin counter-operations against Wallace.

The experience of the Welsh at Falkirk is a bit of a mystery. Walter of Guisborough, an English chronicle, described the Welsh troops rioting on the night before the battle, after getting drunk on wine brought to the English camp at Linlithgow by sea. Edward restored order by sending in his household knights, killing eighty Welshmen and several priests. Guisborough's tale may be doubted: the inventory for the supply ships happens to have survived, and shows the vessels had no alcohol on board. The muster rolls for the campaign, which survive almost entire, show no dramatic fall in numbers among the Welsh.

However, similar problems are also reported by Peter Langtoft and William of Rishanger. The latter wrote that one of the king's knights warned him not to trust the Welsh:

“King Edward, you are mistaken if you put your trust in the Welsh as you once did. Instead, take their lands from them.”

On the day of battle itself, according to Rishanger, the Welsh refused to fight until the Scottish spear-rings or schiltrons were broken. When it became clear the king was winning – and would be asking difficult questions afterwards – the Welsh suddenly rediscovered their enthusiasm:

“The Welsh straightway fell upon the Scots and laid them low, so greatly that their corpses covered the land like snow in winter.”

Iorwerth's part in all this is unknown. He certainly survived the battle, and went on to greater things. In the following years he accumulated more land on Anglesey, until he was one of the wealthiest men on the isle. After a few more stints of military service in Scotland, he retired and died in 1333, quite old and very rich. Iorwerth was far from exceptional, and men like him cannot simply be stuffed under the carpet of history:

“Our thinking about how Wales developed in this period has thus to incorporate both the traditional tale of princely accomplishment, disaster at the hands of Edward I and subsequent colonial oppression, and a newer narrative of the contradictions inherent in achievement, widespread rejection of princely rule and significant accommodation to, and profit from, regime change. It was indeed an Age of Ambiguity.”

- David Stephenson

Published on July 22, 2021 00:43

No comments have been added yet.