David Pilling's Blog, page 24

October 15, 2020

A crash-course in treachery...

Click here Rewind. Let's go straight back to the start of Edward I's career in Gascony and Wales – the details of the former in particular tend to be passed over in Anglo histories, which is a pity because Edward's behaviour suggests he prized Gascony over Wales in this period: one of the many ironies and contradictions of this very peculiar Plantagenet. The man who would one day conquer Wales couldn't wash his hands of the place fast enough as a youth.

Click here Rewind. Let's go straight back to the start of Edward I's career in Gascony and Wales – the details of the former in particular tend to be passed over in Anglo histories, which is a pity because Edward's behaviour suggests he prized Gascony over Wales in this period: one of the many ironies and contradictions of this very peculiar Plantagenet. The man who would one day conquer Wales couldn't wash his hands of the place fast enough as a youth.Thanks to French histories, especially Trabut-Cussac, it is possible to trace Edward's first stint in Gascony in detail. He arrived in the duchy on 10 June 1254, accompanied by his mother Eleanor of Provence, his brother Edmund and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Edward was just fifteen years old.

They arrived at the tail-end of Henry III's expedition to Gascony, where the king had successfully crushed a rebellion of the local gentry. The king was engaged in mopping up the last dregs of resistance, in particular a complicated local revolt centred on Bergerac in the Dordogne. Briefly, the citizens of Bergerac chose to support one Renaud de Pons, a vassal of the King of France who laid claim to the lordship. Henry could not afford to let the French get their tentacles into Bergerac, so he mustered knights and militia from Gascony and laid siege to the town. He also ordered all goods, wines and people coming from Bergerac to be seized.

Edward's first taste of politics was a crash-course in treachery, direct military action and the tangled politics of Gascony. Renaud apparently set a trap for Edward and his family when they landed in the duchy: his intention was to take them prisoner and force Henry to break off the siege. If his attempt had succeeded, he might well have sold his royal hostages to the French. This was audacious stuff, but it didn't come off. Somehow the royal party was warned in time and evaded the trap: they moved quickly, and within 24 hours of arrival Edward was with his father at Meilhan (now the Landes department of Nouvelle-Aquitaine).

The prince was quickly put to work. No sooner had he arrived than Edward confirmed his father's appointment of Stephen Longespée as constable of the castle of Bourg, an important stronghold on the Gironde in northern Gascony. Henry may have intended to show the Castilians that he had a capable heir, worthy of marriage to Alfonso X's daughter, Eleanor. This was important: if the wedding went ahead, that would neutralise the Castilian interest in Gascony and remove any threat of invasion from that quarter. Thus Edward had to be paraded about a bit, like a prize stallion.

to edit.

Published on October 15, 2020 06:07

October 9, 2020

Blood and steel...

Today is the release of my new novel, THE CHAMPION (I): BLOOD AND STEEL on Kindle, with (hopefully) paperback and audiobook versions to follow. Please see links to the Ebook version at the bottom of this post. Today I wanted to describe the background and inspiration for the story, which is loosely based on historical events.

Today is the release of my new novel, THE CHAMPION (I): BLOOD AND STEEL on Kindle, with (hopefully) paperback and audiobook versions to follow. Please see links to the Ebook version at the bottom of this post. Today I wanted to describe the background and inspiration for the story, which is loosely based on historical events. The main character, En Pascal de Valencia, is a knight of Aragon (now modern-day Spain). Pascal was a real person, and was among the household knights of Edward I of England, known as Longshanks or the Hammer of Scots. Pascal seems to have entered Edward's service in the 1280s, when the king's fame and reputation were at their height, and was by no means the only foreign knight in the royal household. There was at least one other Spanish knight, named Jamie, senor de Gerica, along with an Italian and several Germans.

Intriguingly, Pascal is referred to in the household accounts as the 'Adalid'; this translates as Champion or Leader of Hosts, and would appear to mean he was of high rank. His title may relate to a custom observed in Navarre and other kingdoms south of the Pyrenees, whereby men were formally raised to the title of Adalid in a ritual dating back to Antiquity.

Strictly speaking, nobody could achieve the rank of Adalid unless they had first served as an Almocaden or leader of infantry. The footsoldier who aspired to the role would appear before the twelve existing Leaders of the Host, and only be elected if he was found to possess the necessary qualifications. These were: loyalty, experience, lightness of foot and strength of arm. If chosen, the candidate would be taken to the King, who gave him new clothes and presented him with a pennoncel (a banner on a lance) as a sign of his new status. He would then be raised on a shield by his new companions, and issue a challenge to the four corners of the world. This was:

"I challenge all the enemies of the Faith, and of my Lord the King, and of this Land."

While he spoke, the new Champion would cut the air with his sword. He would then be lowered to the ground. His sword would be sheathed, and the King, placing a banner in his hand, would declare him a lawful Adalid. The Champion was now fit to lead knights in battle.

Since he carried the title of Adalid, it seems likely that En Pascal observed this ritual in Aragon before he left his homeland and travelled to England. I have included the ceremony in the story - it was too good to leave out - along with details of Pascal's adventurous military career. These shall be explored in future posts...

Links to Kindle on Amazon US and Amazon

amzn.to/36LBf4y

amzn.to/3lw4VXQ

Published on October 09, 2020 02:55

October 2, 2020

The Champion arrives!

rb.gy/79rwbvTHE CHAMPION (I): BLOOD AND STEEL is now available as pre-order on Kindle! Paperback and audiobook versions to follow...get it while hot and gory!

rb.gy/79rwbvTHE CHAMPION (I): BLOOD AND STEEL is now available as pre-order on Kindle! Paperback and audiobook versions to follow...get it while hot and gory!“I am En Pascal of Valencia, the Adalid, the Champion, the Leader of Hosts, and this is my tale...”

1296 AD: the whole of Western Europe trembles on the brink of war. South of the Pyrenees, the Christian and Moorish kingdoms fight and scheme against each for control of Hispania. To the north, the rival kings of England and France feverishly enlist allies as they battle for supremacy on the Continent. Even as the armies clash, spies and double agents fight their own bloody war in the shadows.

From the safety of old age, En Pascal of Valencia recalls his own exploits in this brutal and treacherous era. As a poor country knight of Aragon, he sets out from home to restore the glory of his famous grandfather, known as the Knight of the Falcon. After winning fame in battle against the Moors, he is forced into exile. With just one loyal servant for company, Pascal is forced to carve out a new life as a mercenary on the battlefields of Aquitaine and Flanders. There he will find love, fame and endless danger...

The CHAMPION (I): BLOOD AND STEEL is the latest historical fiction thriller by David Pilling, author of the Leader of Battles series, Caesar's Sword, The White Hawk, Longsword and many more novels and short stories.

Link to AMAZON UK:

rb.gy/79rwbv

Link to AMAZON US:

rb.gy/79rwbv

Published on October 02, 2020 03:37

September 2, 2020

William the Conqueror

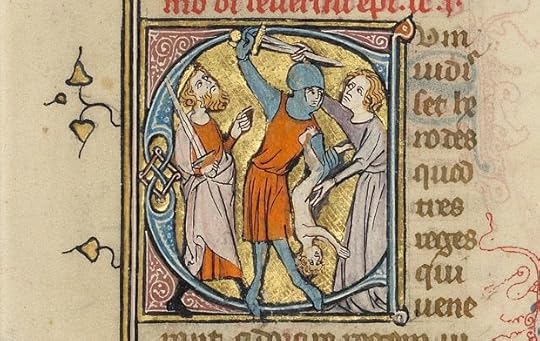

William Wallace's invasion of northern England in the winter of 1297, in the wake of the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge, tends to be described in general terms. For instance the Lanercost chronicle summarises the invasion thus:

William Wallace's invasion of northern England in the winter of 1297, in the wake of the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge, tends to be described in general terms. For instance the Lanercost chronicle summarises the invasion thus:“After this [the capture of Berwick] the Scots gathered together and invaded, devastating the whole country, causing burnings, depredations and murders, and they came almost up to the town of Newcastle, but turned away from it and invaded the county of Carlisle; there they did as in Northumberland, destroying everything, and afterwards they returned to Northumberland, to devastate more fully anything they had overlooked previously; and on the feast of St Cecilia virgin and martyr they returned to Scotland.”

More than enough information has survived, in the form of detailed chronicle and account sources, to paint a more complete picture. Equally, the parallel actions of Wallace's enemy Edward I on the Continent, while the Scots attacked the northern counties, are not generally described in any great depth. I have described Edward's doings in previous blog and Facebook posts, and this one will focus on Wallace.

The initial phase of Wallace's expedition took the form of scattered raids into Northumberland. These began in early October, but the Scots were not massed for a full-scale invasion until around the feast of St Martin (11 November). Several weeks of raiding had spread panic in the northern counties, and many towns and villages stood abandoned after their inhabitants fled to the safety of walled cities. The English were not entirely on the defensive; the garrison at Alnwick, for instance, is said to have ridden out to harass the Scots.

News of the disaster in the north had reached Westminster by late September. Nothing could be done until word was relayed to King Edward in Flanders, whose orders then had to be conveyed back to London. Writs went out for a general muster to resist the Scots on 23 October, but the actual muster date was fixed for 6 December. Wallace thus had plenty of time to wreak havoc before the English could mount an effective response.

Surviving tithe records paint a vivid picture of the damage caused by Wallace's troops. North-east Northumberland was especially badly hit, and a great number of mills and townships burnt. Tithe revenues and rents were cut dramatically; in many places it was said that rents had lapsed 'because the land was waste on account of the Scottish war'. Wallace's men employed the usual terror tactics of medieval warfare. Around the Cheviot hills, for instance, at the vills of Hethpool and Akeld, no bond rents were paid in 1298 because the bondsmen had been slaughtered or driven off by the Scots.

Some of this large-scale destruction was remembered in poetry. The Song of the Scottish War, allegedly composed by a prior of Alnwick, records how Wallace's men had given the town to the flames:

“These wicked men deliver Alnwick to the flames; they run about on every side like madmen...”

Edward's northern subjects would not, of course, have appreciated being reminded that Wallace was responding in kind: in 1296 the English had burnt and slaughtered in Scotland with equal abandon, and mocked the Scots as a 'sorry shower' incapable of defending their land. But that was politics. The real victims on both sides were the suffering peasantry, forced to flee their homes or butchered like animals by marauding bands of soldiers.

Wallace's own actions are of great interest. Shortly after Martinmas (11 November) he descended upon Carlisle and laid siege to the city. On arrival he sent a clerk to the citizens to demand surrender in the name of 'William the Conqueror'. The demand was refused, but it might suggest a nice touch of humour on Wallace's part, since the Conqueror was Edward's famous ancestor. Lacking siege equipment to storm Carlisle, he left a detachment to hold the garrison in check while he took his army through Inglewood, Cumberland and Allerdale all the way to Cockermouth, 'devastating everything' as he went.

Meanwhile Edward's captains in the north were struggling to muster their levies. Robert Clifford, ordered to assemble armed men at Carlisle, actually killed a man for refusing to join up. It seems the shocking defeat at Stirling Bridge had temporarily destroyed English morale, and that few were willing to ride out and face the invaders. The men of Newcastle proved the exception. Despite being outnumbered, they marched out to block the advance of Wallace's army:

“For the courageous men who were in charge of Newcastle braced themselves and went out of the city a little way, despite the fact that they were very few against many. Seeing this, the Scots veered away from the city, divided among themselves the spoils, and handing over to the Galwegians their share, they departed to their own regions.”

By this point Wallace's army may have been depleted by cold and hunger. The weather was appalling, and many Scots were said to have perished in a snowstorm sent by St Cuthbert to protect the bishopric of Durham. Faced with a mob of angry Geordies on the one hand and the fury of St Cuthbert on the other, Wallace chose to turn north and re-cross the border into Scotland on 22 November. Further Scottish raiding parties appear to have ravaged the northern counties after that date, but the English had found a second wind. Shortly before Christmas 1297 the pugnacious Clifford led a raid into Annandale, while Earl Warenne – smarting from his humiliation at Stirling Bridge – was given command of a second northern army to replace the one he had so carelessly lost.

Published on September 02, 2020 05:37

August 31, 2020

Convict-soldiers

From October 1297-January 1298, while at Ghent, Edward I issued letters of pardon for over 300 convicted thieves and murderers. These men had been transported over from England to bolster the army in Flanders: Edward's subjects had no desire to fight overseas, so he was forced to scrape out the prisons to fill the ranks.

The surviving pardons give us some idea of what these convict-soldiers were like. For instance, on 14 October the king issued a pardon to three murderers:

“Mandate to make letters of pardon to William Durant of Bettelegh for the death of John his brother, Henry Pollard of New Castle for the death of Geoffrey de Knotton of New Castle and Richard de Porta of Talk for the death of Alan son of Alan de Rugges; because they are staying with the king on his service.”

Etc. After the truce with the French on 9 October, Edward had a problem. Military discipline in this era was virtually non-existent, and the only way to control these convict-soldiers was to make their pardons conditional on good service i.e. they only received pardons at the end of a campaign, so long as they had behaved themselves.

The truce meant that the war was effectively over, but Edward could not simply withdraw from Flanders. Some histories of this reign give the impression he simply ditched his allies on the Continent and rushed home to deal with William Wallace. Nothing could be further from the truth: Edward was enmeshed in all kinds of treaty and financial obligations, and another ten months would pass before the battle of Falkirk.

To get the best deal possible for himself and his allies, Edward had to maintain a military presence in Flanders. Otherwise Philippe le Bel would have simply brushed aside the peace talks and carried on attacking the Flemings. Months of negotiations lay ahead, and all that time Edward's army – composed of English convicts and notoriously undisciplined Welsh archers – lay billeted at Ghent. The fighting had petered out, and the troops had nothing much to do except drink and kick their heels. Now the convicts had their pardons, there was little to restrain them. Trouble was brewing.

Published on August 31, 2020 02:28

July 22, 2020

The Battle of Falkirk

At dawn on 22 July 1298 the English army, led by Edward I in person, marches through the deserted streets of Linlithgow. It is tired and hungry. None of the soldiers have eaten since the previous day. The king himself is nursing two broken ribs after his horse trod on him during the night. For weeks he has wandered through south-west Scotland, hunting William Wallace. The Scottish leader has led Edward a merry dance through a burnt and wasted landscape, but now the dance is almost over. Acting on a tip-off from a Scottish spy, the king has finally tracked down his quarry.

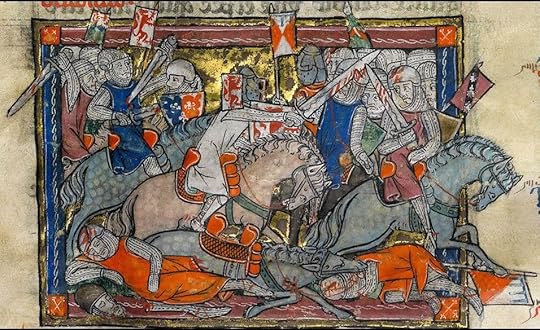

At dawn on 22 July 1298 the English army, led by Edward I in person, marches through the deserted streets of Linlithgow. It is tired and hungry. None of the soldiers have eaten since the previous day. The king himself is nursing two broken ribs after his horse trod on him during the night. For weeks he has wandered through south-west Scotland, hunting William Wallace. The Scottish leader has led Edward a merry dance through a burnt and wasted landscape, but now the dance is almost over. Acting on a tip-off from a Scottish spy, the king has finally tracked down his quarry.A band of Scottish spearmen are glimpsed on the hill opposite Linlithgow. Some of Edward's men rush forward to attack, but the Scots have vanished. The king orders his tent to be pitched on the brow of the hill, so he and the bishop of Durham can hear the mass of Magdalene. It is her feast day.

As the sun rises, the entire Scottish host can be seen drawn up on the side of a hill near Falkirk. Wallace has set up his army like a human fortress. Most of his infantry are armed with twelve-foot spears, arranged in four bristling circles or schiltrons. Each schiltron is made up of two rings of spears, linked together and pointing in all directions. For extra protection they are surrounded by fences of stakes tied together with ropes. Between the schiltrons Wallace has placed his archers under Sir John Stewart of Bonkyll, second son of the High Steward of Scotland and uncle of the Black Douglas. Behind the infantry Wallace posts his cavalry, a few hundred knights and men-at-arms.

When informed of all this, Edward hesitates. He proposes to give his soldiers a meal before they go into battle. His captains say this is too risky, since the armies are only divided by a narrow stream. While the men eat, the Scots might attack. This is most unlikely, but Edward is no fit state to argue.

“Be it so,” he says wearily. “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.”

The first division or 'battle' of English heavy cavalry rumbles forward, led by the earls of Hereford and Lincoln. They gallop straight into a bog in front of the Scottish position. While the Scots hoot and jeer, the English struggle out of the mud and ride about to the western end of the Scottish position. Meanwhile the second battle, led by the fighting bishop of Durham, veers off east to avoid the bog. The bishop orders his men to halt until the third line of English cavalry have come up in support. One of his knights, Ralph Basset of Drayton, sneers at his commander:

“It is not your business, bishop, to teach us about battle. You understand Mass. Go and celebrate Mass, and leave the fighting to us.”

The bishop's knights charge and hurl themselves at the nearest schiltron. Meanwhile the first battle has worked its way round to the west and attacked Wallace's archers. At this point most of the Scottish cavalry turn about and quit the field. As the English cavalry charge home, Wallace roars to his men:

“I have brought you to the ring, now dance if you can.”

His bowmen are slaughtered. The English turn their attention to the schiltrons. They kill some of the men in the outer rings, but cannot batter their way through the hedge of spears. The king comes up with the infantry. His Welsh troops are in a bad mood and refuse to fight, but he still has over ten thousand English and Irish to deploy. These include bowmen of the High Peak in Derbyshire and companies of slingers from Nottingham.

Every archer carries twenty-four arrows in his quiver. They swarm forward and loose a storm of missiles at the schiltrons, who can do nothing but soak it up. When they run out of arrows, some of the English pick up stones and lob them at the Scots. As the schiltrons disintegrate, Edward utters a suitably pious exclamation:

“If the Lord is with me, who will stand against me?”

Now the Welsh decide they would rather be on the winning side. Thousands of bare-legged, red-cloaked Welshmen storm onto the field and tear apart the shattered schiltrons. Wallace's men break, only to be hunted down by the Welsh and butchered in droves. Their bodies are heaped across the moor, says an English chronicler, like snow in winter.

Wallace escapes. Some writers later claim he fled with the Scottish cavalry and left his footsoldiers to their fate. Others say he dismounted and fought among the schiltrons until all was lost. Whatever the truth, he gets away. Thousands of his men do not. The English suffer the loss of over three hundred horses, skewered on Scottish spears, but very few men. Their most notable casualty is Sir Brian de Jay, Master of the Templars, pulled down and killed by the Scots after his horse floundered in the bog.

After the battle Edward's victory is celebrated in a rhyme composed by the monks of Lanercost priory:

“Berwick, Dunbar and Falkirk too,

Show all that traitor Scots can do,

England rejoice! Thy prince is peerless.

Where he leads, follow fearless.”

Another contemporary poem, the Song of the Scottish Wars, remarks of the battle:

“The white thorns are cut down, while the black bilberries are gathered; Wallace, thy reputation as a soldier is lost.”

Published on July 22, 2020 01:09

July 17, 2020

Crisis? What crisis?

In July 1298 an 'English' army under Edward I tramped through Galloway, hunting the Scots led by Sir William Wallace. The king had brought an enormous host to Scotland: 28,000 men, including 2000 heavy cavalry and 14,000 Welsh infantry. After his final conquest of Wales in 1295, Edward milked the manpower of the principality on an unprecedented scale.

In July 1298 an 'English' army under Edward I tramped through Galloway, hunting the Scots led by Sir William Wallace. The king had brought an enormous host to Scotland: 28,000 men, including 2000 heavy cavalry and 14,000 Welsh infantry. After his final conquest of Wales in 1295, Edward milked the manpower of the principality on an unprecedented scale. It was all a far cry from the previous year, when the king had struggled to scrape together an expeditionary force to take to Flanders. The usual explanation is that Wallace's victory at Stirling Bridge in September 1297 galvanised Edward's kingdom, and dragged it back from the edge of civil war. Thus, the shining moment of one of Scotland's most famous sons only served to unify his enemies. So the theory goes.

This view has been challenged in recent years, notably by Dr Andy King in the recent volume on Edward I. King points out that defeats such as Stirling Bridge tended to have the opposite effect: for instance, the disaster of Bouvines did not inspire King John's subjects in England to rally behind him. Instead it helped to trigger a civil war. Equally, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd's successes against Henry III in 1257 only inflamed tensions in England. Nor can Edward II's catastrophic defeat at Bannockburn in 1314 can be said to have had any kind of unifying effect. Instead his political opponents in England exploited the king's defeat to enforce wholesale concessions, while Thomas of Lancaster imposed his brief authority over Edward.

By contrast, in July 1298, just months after a summer of heated political controversy over his methods of finance and recruitment, Edward I led an enormous host into Scotland. Certainly the largest seen in the British Isles since 1066, or would be seen again before the seventeenth century. Among those accompanying this army were the earls of Norfolk and Hereford, who had been the king's most vocal critics in 1297.

The reality is that Edward's critics had demanded concessions from the king, and got them after a few months of bickering. The so-called 'crisis' went no further, and what followed in 1298 was an extraordinary demonstration of unity between the crown and baronage.

Published on July 17, 2020 07:18

July 11, 2020

The dancing pope

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Courtrai in 1302, in which Flemish urban militia inflicted a shattering defeat on the cream of French chivalry (curdled cheese by the end of it). This wasn't the first time an army of infantry had defeated mounted knights - witness Stirling Bridge in 1297, for instance - but it was still an utterly shocking turn of events. This post will examine the profound consequences of the battle from an English point of view.

Today is the anniversary of the Battle of Courtrai in 1302, in which Flemish urban militia inflicted a shattering defeat on the cream of French chivalry (curdled cheese by the end of it). This wasn't the first time an army of infantry had defeated mounted knights - witness Stirling Bridge in 1297, for instance - but it was still an utterly shocking turn of events. This post will examine the profound consequences of the battle from an English point of view. The situation Edward I found himself in at the start of 1302 is best described as deadlock. He was at war in Scotland and stuck in an unresolvable situation on the Continent, where his war against Philip IV had petered out into a series of annually renewed truces. Edward's troops had managed to recover a portion of his duchy of Aquitaine, invaded by the French in 1294, but subsequent negotiations had gone around in circles. The pope, Boniface VIII, asked both parties to submit their parts of Aquitaine to his custody, so he could arbitrate between the two kings. Edward was willing to hand over his share, but Philip absolutely refused to do likewise. This was probably because the French king was perfectly aware that his invasion of Aquitaine was illegal, and that Boniface would find in Edward's favour.

In Scotland the situation was equally messy. The English had made some military gains in the south-west in the summer of 1301, but Edward's desire for a final resolution was scuppered by the usual lack of money and supplies. He decided to spend the winter in Scotland, probably to protect his gains which would otherwise have fallen back into Scottish hands. The problems of supply and desertion became acute, and in January 1301 Edward was obliged to agree to a truce with the Scots. This gave him time to resupply his existing garrisons in Scotland, and in that context was a blessing in disguise. There is no doubt, however, that Edward only agreed to the truce because he had little alternative. The king himself made no bones about it, and expressed his fear that the exiled king of Scots, John Balliol, would soon return with a French army at his back:

"It is feared that the kingdom of Scotland may be removed from out of the king's hands (which God forbid!) and handed over to Sir John Balliol or his son..."

The truce of Asnieres, negotiated in France, has been overshadowed by the game-changing Flemish victory at Courtrai. In January 1302 Edward agreed to hand over all the lands and castles he had taken in Galloway (south-west Scotland) to the custody of French officials. They would hold them for the duration of the truce, to expire on 1 November, when the French were supposed to hand them back.

There are several odd clauses about this treaty. Edward had been burnt once before like this, when he agreed to hand over key towns and castles in Aquitaine to Philip's officers in 1294. The French were supposed to hand them back after a grace period of forty days, but instead Philip broke his word and declared Aquitaine forfeit. Now he was trying the same trick in Scotland.

Edward had no intention of being burnt twice. Between August 1301 and February 1302, even as his diplomats in France said 'yes' to every French demand, he continued to stock and provision his garrisons in Scotland. In short he was calling Philip's bluff. The French were supposed to send men to Scotland by 16 February 1302 to take custody of the lands in the southwest. Edward took a gamble, and it paid off as the 16th came and went without a Frenchman in sight. This meant that Philip had broken the terms of his own treaty, and Edward was free to keep his conquests in Scotland.

The real question is why did Philip implement the treaty in the first place, if he had no intention of delivering on it? By failing to send men to Scotland on the agreed date, he missed an opportunity to humiliate Edward and seize control of a very large chunk of Scottish territory. It may be that the French king was simply playing for time, and chose to hold Edward and the Scots at arm's length while he contemplated his options elsewhere.

Clever old Philip. What he did not predict - nor did anyone else - was the obliteration of his field army in Flanders on 11 July 1302. This was every bit as shocking a defeat as Stirling Bridge was for the English, and with much wider consequences. In the space of a single terrible, blood-soaked day, Philip's position crumbled away like dust. His enemies rejoiced. When informed of the wonderful, impossible news, Pope Boniface is said to have leaped out of bed and danced a jig. As for the English, the sound of their laughter could be heard all the way across the Channel.

Published on July 11, 2020 01:30

July 3, 2020

The fifth man

This post is based on brand-new and original research by Dr David Stephenson on the revolt of Prince Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5. The information is drawn from a fantastic new study of medieval Wales, only just released (see cover above).

This post is based on brand-new and original research by Dr David Stephenson on the revolt of Prince Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294-5. The information is drawn from a fantastic new study of medieval Wales, only just released (see cover above).Every previous account of the revolt has stated that the Welsh who revolted against Edward I had four leaders. These were Prince Madog himself, Morgan ap Maredudd, Maelgwn ap Rhys Fychan and Cynan ap Maredudd. We know more about Madog and Morgan than the latter two. Madog was a member of a cadet branch of the House of Aberffraw and a hereditary foe of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Along with many other Welshmen, he fought for Edward against Llywelyn in 1277, but in 1294 raised the standard of revolt and proclaimed himself Prince of Wales. Morgan was a lord of Glamorgan in the south-west and a member of the old royal house of Gwynllwg.

New research reveals there were five leaders of the revolt, not four. The fifth man was Meurig ap Dafydd, who led the rebellion against the English in Abergavenny in Gwent. This is revealed in the memoranda to a version of Brut y Twywsogion (Chronicle of the Princes) held at Trinity College, Dublin. Under the year 1294, after naming the other Welsh leaders, the annal reads:

"Item, the Welsh of Gwent made Meurig ap Dafydd their lord."

So who was the fifth man, and what can be made of this brief notice? Meurig ap Dafydd appears in other records. In 1279 he was in dispute with the burgesses of Abergavenny, and in 1285 was among a list of witnesses to a charter of John de Hastings, lord of Abergavenny. Most interestingly, in 1292 he was serving as one of the chief royal tax collectors of the district.

There is nothing to suggest that before 1294 Meurig was anything other than a crown loyalist, or that he had ever fought against the English. Instead he was among that class of Welsh freemen or 'uchelwyr' who served in the royal administration and had no qualms about actively assisting the Edwardian conquest of Wales. In some ways the motives of such an individual are more interesting than those of princes and great lords, but otherwise we know very little about Meurig. One of the main grievances of the Welsh in 1294 was the heavy taxation imposed on them by Edward's government, and it seems odd that a tax collector should have joined in the protest. We may speculate that Meurig witnessed the oppression of the English regime at first hand, and was unwilling to be part of it any longer.

The notice in the Brut at least allows us to make sense of events in the south-west. Morgan ap Maredudd was previously thought to have led the revolt in Glamorgan and Gwent. He later claimed to be in revolt against Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and lord of Glamorgan, rather than against the king. In Glamorgan he only attacked castles and towns owned by the Clare family, but in Gwent the Welsh attacked the castle of Abergavenny, which was not a Clare stronghold. Now it appears Meurig led the revolt in Gwent, Morgan's actions become clear. His revolt was indeed directed against Clare, which explains why King Edward was so ready to pardon him.

Meurig's revolt in Gwent ended badly. On 13 February 1295 his men were attacked by an army led by Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford. The Annales de Wigornia describes what followed:

"On the 13th of February the Earl of Hereford, with other nobles and the levy of the district, raised the siege of the castle of Abergavenny in which the Welsh were engaged, and burnt their lands, carried off a great deal of plunder, and slew innumerable people."

The fate of Meurig is unknown. Perhaps he was among the slain when Hereford broke the siege of Abergavenny, or died in the rout afterwards. It could be that he followed Morgan's example and made his peace with the king, but at present the record is silent.

Published on July 03, 2020 05:06

July 2, 2020

Battle for the empire

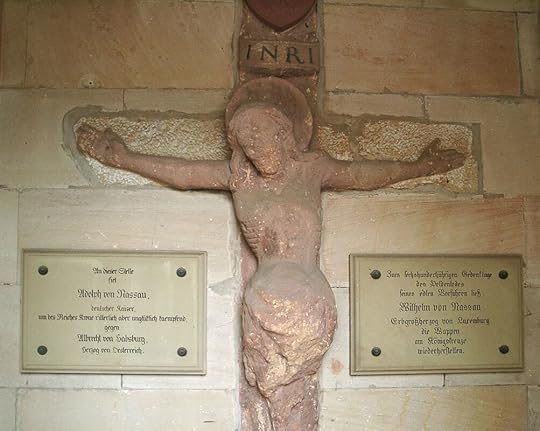

The King's Cross, set up to commemorate the defeat and death of Adolf of Nassau On 2 July 1298 the armies of Adolf of Nassau and Duke Albrecht of Austria faced each other at Göllheim, between Kaiserslautern and Worms in south-west Germany. The battle was fought over the decision of the prince electors of the Holy Roman Empire, without electoral act, to dethrone Adolf as King of the Romans and replace him with Albrecht.

The King's Cross, set up to commemorate the defeat and death of Adolf of Nassau On 2 July 1298 the armies of Adolf of Nassau and Duke Albrecht of Austria faced each other at Göllheim, between Kaiserslautern and Worms in south-west Germany. The battle was fought over the decision of the prince electors of the Holy Roman Empire, without electoral act, to dethrone Adolf as King of the Romans and replace him with Albrecht.There was a long-standing rivalry between the two. Albrecht was meant to be elected king in 1291, but the electors considered him too powerful and feared a hereditary monarchy: Albrecht's father, Rudolph I, had been the previous king. Instead they elected Adolf in the belief that he would principally serve the interests of the electors. Adolf was relatively poor, and had to agree to make all kinds of concessions to the electors in exchange for their support. In short, they wanted a puppet king.

Adolf proved to be the opposite. In 1294 war broke out between England and France, which gave him an opportunity to extend his power base within the empire. Edward I of England recruited Adolf as part of his 'Grand Alliance' against the French, and agreed to pay him £60,000 in English sterling for his services. This was to be paid in three instalments. The first two were paid over by Christmas 1294, but instead of fighting the French Adolf used Edward's money to wage war against his own subjects. In two bloody and brutal campaigns he annexed Thuringia and other lands in east-central Germany and added them to his power base. Now he could rule in deed as well as in name.

Adolf's policy backfired. The wars in Thuringia alienated his subjects, and his misuse of English money angered the nobles, who thought he should have distributed it among them. His growing unpopularity gave the electors an excuse to formally depose Adolf, and in June 1298 they declared he was unworthy of office and had forfeited his royal dignity. Duke Albrecht of Austria was then invited to take the crown.

Adolf was determined to fight for his rights. The two sides raised armies and advanced to meet in pitched battle at Göllheim. It was unusual for a war in this period to be decided by a single battle, but the issue had to be settled quickly. Which of these men would sit on the imperial throne?

On 2 July Albrecht positioned his troops in a strategically favourable position on the Hasenbuhl, a hill near the village of Göllheim. The exact size of the armies is unknown, though Albrecht would have raised men from his duchies of Austria and Styria, as well as contingents from the Hapsburg territories of Hungary and Switzerland and those of his ally Henry II, Prince-Bishop of Constance. Adolf's men were drawn from his home county of Taunus, the Electoral Palatinate within the empire, Franconia, Lower Bavaria, Alsace and St Gallen.

The battle itself, otherwise known as The Battle of Hasenbuhl and the King's Cross, lasted from early morning until later afternoon. There were three separate engagements, and the battle remained undecided for many hours. At last, in the third and decisive engagement, Adolf tried to cut his way through the press and kill his rival in person. According to a French chronicle, the Chronia Regum Francorum, Adolf was thrown from his horse by a Welshman:

"And though King Adolph acted with vigour that day, in the end, however, a Welshman leaped onto his horse behind him and tried to cut his throat; when he was unable to do so, he dropped his weapons and threw him onto the ground where he was immediately captured by the duke of Brabant. The duke of Austria also saw this and ordered his head cut off by one of his squires."

If this account can be trusted, Adolf's downfall was brought about by a Welsh soldier in the service of Duke Albrecht. Why would a Welshman have been present at a battle in Germany? The obvious conclusion is that he was an agent of Edward I, sent by the English king to exact revenge on Adolf. Edward had his hands full at this time with the campaign in Scotland against William Wallace, but it seems he had not forgotten the man who stole his money a few years earlier. Other accounts state that Adolf was unhorsed by Albrecht himself, and then cut to pieces on the ground by Austrian soldiers.

Whatever the truth, Adolf was killed on the field and his army immediately took to flight. Albrecht was crowned King of the Germans at Aachen Cathedral on 24 August. He got to savour his truimph for ten years, until he was murdered at Windisch on the Reuss River by his nephew Duke John of Swabia, afterwards known as Duke John the Parricide. And so it went on.

Published on July 02, 2020 01:30