David Pilling's Blog, page 27

May 29, 2020

To the woods and fields

The death of Simon de Montfort and most of his captains at Evesham in 1265 left their supporters in England scattered and divided. When the war of the Disinherited blew up the following year, the rebels had to adopt new tactics.

Many of the Disinherited abandoned their castles and took to what we would call guerilla warfare - ‘to the woods and fields’, as one chronicler put it. In this respect their strategy was very similar to that of the Scots in the Wars of Independence. Both deliberately avoided battle and operated from hideouts in wild country: the forest of Selkirk in the case of the Scots, the meres and fens of Ely and Axholme in the case of the Disinherited.

Unable to face the superior forces of Henry III in open battle, the Disinherited switched to hit-and-run tactics and hitting royalist supply lines. This kind of strategy was nothing new, and indeed central to medieval warfare. As Robert Wace, a twelfth century Norman poet, expressed it:

“Go through this country with fire,

destroying houses and towns,

take all booty and food,

pigs and sheep and cattle.

Let Normans find no food

Nor any thing on which to live.”

The rebel bands in the midlands lurked along the Great North Road, the main artery of trade and commerce linking north and south. From their base at Axholme, they rode out to plunder royalist merchants moving up and down the highway. One of their particular targets was Peter Beraud, one of the Lord Edward’s Italian creditors. They even attacked foreign dignitaries. In the summer of 1267, Alexander the Steward of Scotland was waylaid inside Sherwood Forest and held prisoner until his ransom was paid.

Many of these exploits have a distinctly Robin Hood flavour, which may be no coincidence. Later chroniclers such as Walter Bower placed the famous outlaw hero among the Disinherited in 1266, though he also made clear his disapproval:

“In that year also the disinherited English barons and those loyal to the king clashed fiercely, amongst them Roger de Mortimer, occupied the Welsh Marches and John de Eyvill occupied the Isle of Ely; Robert Hood was an outlaw among the woodland briars and thorns. Between them they inflicted a vast amount of slaughter on the common folk, cities and merchants”.

Another rebel tactic was to attack the Jewish communities in England. This was a way of wiping out their debts while also destroying a useful source of credit for the crown. The poor Jews themselves were left defenceless against the onslaught of savage fighting men.

In 1266 a band of Disinherited swooped down upon the Jewish quarter in Lincoln. They razed the synagogue, destroyed charters and deeds and butchered scores of innocents:

“That they have taken Lincoln, the Jews now

They take and destroy, breaking open the coffers;

Charters and deeds and whatever is injurious

To the Christians they have taken,

Treading them under foot,

Among the lanes, and woman and child,

They have put to the sword a hundred and sixty”.

Such ruthless tactics enabled the Disinherited to sustain a war of attrition for several years. They were up against some able opponents. Henry III himself, not renowned as one of England’s warrior-kings, could soldier when he really put his mind to it: witness his victory at Northampton in 1264, for instance. His heir the Lord Edward was an energetic and supremely confident military leader, while other royalist captains such as Henry of Almaine, Earl Warenne and Roger Leyburn were all formidable.

Outnumbered and out-resourced, the Disinherited had to find new leaders, and quickly. Their search for the next Simon de Montfort will be the subject of another post.

May 28, 2020

Warring cousins

One of the many side-dramas of the Montfortian era in England was the bitter ongoing feud between the Lord Edward (later Edward I) and Robert de Ferrers, 6th earl of Derby (1239-79). These men were cousins, and very alike in some ways: both were ambitious, belligerent, full of energy and willing to stoop to low methods to gain their ends. They differed in that Edward learned from his mistakes, while Robert seemed intent on compounding his.

The arms of the 6th earl

The arms of the 6th earlThe origins of their feud are debatable. It may have stemmed from Edward’s sale of his cousin’s wardship to the queen and Peter of Savoy in 1257, though such transactions were not uncommon. Equally it may have stemmed from mere personal animosity between men who were too similar to endure each other’s presence. Whatever the case, it soon led to conflict.

Robert struck first. In 1263, when the whole of England was on the verge of civil war, he attacked and captured three of Edward’s castles. Which ones are not stated, though Robert probably focused on ravaging his kinsman’s estates in Derbyshire and the High Peak country. In early February he turned south and sacked Worcester, destroying both the town and the Jewry. On 5 March he almost had Edward cornered at Gloucester, but the latter managed to slide out of the trap by tricking Henry de Montfort into accepting a truce. Robert was so furious at Henry’s gullibility he ‘struck in his spurs’ and galloped off back to the north country.

Chartley castle

Chartley castleA few weeks later, after the royalist victory at Northampton, Edward went on the offensive. He blazed through Robert’s lands in Derbyshire, throwing down castles and extorting protection money from the earl’s tenants. This was part of a two-pronged campaign: at the same time Edward’s ally, Prince Dafydd of Wales, led an army of Marchers over the border to ravage the Ferrers estates in Staffordshire. Robert was in London with Earl Simon, apparently unwilling or unable to defend his lands.

The wheel of fortune took another dramatic spin at the Battle of Lewes on 14 May, where Edward and his father, Henry III, were captured. This enabled Robert to launch a counter-offensive and chase Dafydd back into Wales. He was then attacked from an unexpected quarter. In December Earl Simon summoned Robert to London to answer ‘divers trespasses’ in the king’s name. He duly turned up and was thrown into the Tower. Either Robert’s actions had got out of hand, or Simon used them as a pretext to imprison the earl and seize his lands.

After Simon’s death at Evesham in August 1265, Robert was handed an opportunity to redeem his fortunes. Both Henry and Edward were willing to take him back into the fold, and he was offered a royal pardon. For reasons that are still unclear, Robert threw the offer back in their faces and went back into rebellion. He and his allies were defeated at Chesterfield in May 1266, where Robert didn’t exactly cover himself in glory. He was discovered hiding under a pile of woolsacks in a local church, and sent to prison at Windsor in a cage mounted on a wagon.

In 1269, after three years of captivity, Robert was swindled out of his inheritance. In one of the great medieval stitch-ups, the king and his sons forced the earl to sign away his lands under impossible terms of recovery. They were granted to Henry’s second son, Edmund, who became Earl of Lancaster. This formed the basis of the great Duchy of Lancaster enjoyed by John of Gaunt, Henry of Bolingbroke et al.

In a later age Robert’s head would have decorated a pike on Tower Bridge. Instead his life was spared. After the death of Henry III and Edward’s departure on crusade, the now-landless earl mustered his followers and tried to recover his lands by force. In 1271 he briefly occupied one of his estates in Berkshire, only to be driven away by Edmund of Lancaster. Two years later he popped up again in Staffordshire and stormed Chartley Castle, one of his old strongholds.

England was now threatened with another civil war. Robert gained the support of Earl Warenne and Earl Gilbert de Clare, while his lieutenant Roger Godberd waged a guerilla campaign in the Midlands. Ferrers loyalists in the High Peak launched attacks on Nottingham, and swore an oath to kill Edward when he returned to England. The situation was rescued by the prompt action of the regents. Edmund and his colleagues Roger Mortimer and Reynold Grey raced north to crush the northern conspiracy, and in 1274 Chartley was retaken in a brutal assault that slaughtered most of Robert’s surviving followers.

The fugitive earl escaped into the wild. When Edward finally returned, the new king took a surprisingly conciliatory line. Instead of destroying his old foe, he allowed him to sue for his lands at law. Robert managed to regain the manor of Chartley (though not the castle, which was staffed by a royal garrison) and the manor of Holbrook in Derbyshire. Thus he redeemed a fragment of his inheritance, and regained a stake in the landed affairs of the realm. Robert was quiet for the rest of his days, which were short: he died of the gout in 1279, aged just forty.

Old resentments died hard among the medieval aristocracy. Robert’s heir, John Ferrers, spent his life lobbying unsuccessfully for the return of his father’s estates. Perhaps to get him out of the kingdom, Edward II made John seneschal of Gascony and packed him off to govern the duchy. This proved a disaster as John deliberately ill-treated the Gascon nobility in order to cause trouble for the king. Even Philip IV of France, no friend to the Plantagenet regime, was moved to declare:

“The said John de Ferrers, we learn, behaves thus because just as the late king of England disinherited the said John’s father, so he wishes to disinherit his and our son Edward II, but may this enterprise, with God’s help, not succeed; but, if it is true, let him perish in his iniquity”.

Philip’s wish came true. The Gascon gentry had a straightforward method of dealing with oppressive outsiders, and arranged to have John murdered. He died of ‘noxious poison’ in 1312, the luckless son of a luckless father.

May 27, 2020

Nothing left to lose

Who were the Disinherited? Confusingly, this term applies to two sets of baronial rebels within the British Isles. These were the rump of the Montfortian resistance in England after the battle of Evesham in 1265, and a group of Anglo-Scottish magnates who continued to fight for the Balliol cause in Scotland in the early fourteenth century.

My focus is on the English rebels, who are the subject of my new book: Rebellion against Henry III, the Disinherited Montfortians 1265-1274, hot off the press (if somewhat delayed thanks to Covid-19) and published by Pen & Sword.

The rebellion in England resulted from the decision of Henry III and his advisors to disinherit all surviving Montfortians, after Earl Simon and most of his chief supporters had been obliterated at Evesham. At first there were hopes of a peaceful settlement to the war, but any tentative efforts at reconciliation were soon dashed. Henry and his heir Edward were under severe pressure from their supporters, who wanted to be compensated for their loyal service. The tension was ratcheted up by Simon’s son, Simon the Younger, who refused to surrender. At the same time his mother, the widowed Countess Eleanor, continued to hold out at Dover. Pirates from the rebel-held Cinque Ports attacked royal shipping in the Channel.

Long before Henry announced his new policy, many of his supporters had already started to prey on the defeated rebels. On 6 August, two days after Evesham, the rapacious Earl Gilbert de Clare instructed his tenants to help his officers in their work of seizing ‘the lands of our enemies’. Clare had worked out a strategy: he was far more concerned with money than land, and his general practice was to seize the rent money for Michaelmas (29 September). He might have taken the rents as a reward for his labours on behalf of the king, or Edward may have promised them to him as a bribe for his support.

Thus the process of disinheritance was well underway before the re-opening of parliament on 13 October. It could be argued that all Henry did was formalise it, and that he had little choice in the matter. Nevertheless, the consequences were disastrous. Within a few weeks England was in the process of a territorial revolution, in which confiscated land and property was carved up among the king’s supporters. This left hundreds of men destitute, including many who had never supported the Montfortian regime in the first place. In the general scramble for free land and cash, such niceties were swept aside.

Inevitably, those who lost out snatched up the swords they had so recently laid at the king’s feet. They had nothing left to lose, and men in such a position may as well go down fighting. The war of Saint Simon was over; the war of the Disinherited had begun.

May 26, 2020

Edward I: New Interpretations

To paraphrase the late, great RR Davies, Edward I of England is the second most divisive figure in British history after Oliver Cromwell. Since the 1950s his reputation among historians has jerked up and down like the proverbial yo-yo, influenced by the usual drivers of revisionism and counter-revisionism. The perception of the general public is a different matter: to them Edward I is the pantomime villain of Braveheart and various popular novels, as well as the go-to bogeyman for Welsh and Scottish nationalists.

In recent years Edward’s reputation has been somewhat rehabilitated. From the cyclic low of the early 1970s, historians such as Caroline Burt, Andrew Spencer and Andy King have all presented more positive appraisals of the reign, while Michael Prestwich - the Godfather of Edwardian studies for the past forty years - has revised the negative assessments of his early career. This latest study, Edward I: New Interpretations, continues the general upward curve while also highlighting Edward’s flaws and failures.

To begin with, this is not a biography in the style of Prestwich or Marc Morris. Instead the editors, Spencer and King, have compiled a series of essays by different contributors. Each chapter addresses different aspects of the reign. These range from Edward’s administration of justice before he came to the throne, his relationship with Scottish magnates, his veneration of the Virgin Mary, and so on. Each contributor has published on their chosen subject and the depth of research and analysis is impressive, even if one doesn’t always agree with the conclusions.

There is much more good than bad to be found in this volume, so it might be easier to deal with the latter first. Edward’s life and times were packed, and it is impossible to cover everything in a book that struggles to reach the 200-page mark. There is no mention of Wales, the Jews, Gascony, the Holy Land, Edward’s relations with Philip IV and other European monarchs, Flanders, the Grand Alliance, the Riccardi, Simon de Montfort, Charles of Salerno, Henry of Castile, William Wallace, Robert de Bruce…the list goes on, and might indeed go on forever. The editors were obviously working within space limits, but their choices are arguably questionable. Should the conquest of Wales, for instance, be relegated at the expense of Edward’s devotion to the cult of Mary? The latter, it is true, casts fresh light on the king’s religious devotions: yet one might argue that this is a side-issue at best, compared to his controversial relations with the Welsh. A chapter by David Stephenson, who has written extensively (and recently) on Edwardian Wales, would have been ideal.

Otherwise it is difficult to fault the evidence and arguments presented here. My personal favourite is Kathleen Neal’s eye-opening discussion of the nature of letters and discourse in this era. I was vaguely aware that kings did not pen their own correspondence, but the subtlety and labour that went into producing just one royal letter or instruction almost defies belief. As Neal elaborates, royal correspondence was very much a team effort, composed by specialist clerks trained to enact the king’s will. Michael Brown’s article on Edward’s ultimate failure to conquer Scotland, based on his fundamental inability to understand the Scottish magnates, comes a close second. Again, though, the decision to omit Wales and include Scotland seems odd. A comparison between the Scots and Edward’s more successful relationship with the Welsh gentry would have been apt.

I may as well address the sullen, glowering elephant in the room. For those whom Edward Longshanks is simply the Big Bad, a cardboard prop to pre-conceptions and emotional needs, a book such as this will hold little interest. Any positive assessment of this particular Plantagenet tends to get written off as a whitewash, a twisted attempt to rehabilitate medieval England’s very own Stalin (or, at best, Khrushchev). Nothing sticks like a good cliché, especially with a grudge to compel it. One can argue that Edward was no different in his attitudes and behaviours - repellent as they may seem - than most of his peers, but in the end it gets boring. Why bother? To paraphrase another clever chap, whose name escapes me at the moment: I have tried these people in the morning, and in the evening, and found in them nothing but spite. Let them bide.

To be less condemnatory for a moment, there is also the issue of price: the book retails at about £60. This is common among specialist publishers, but scarcely calculated to make it leap off the shelves. As a result the fresh arguments and ideas presented here will disseminate among a very small audience, which makes me wonder who the book is aimed at. Is it meant to appeal to the general reading public at all, or a strictly limited academic/university circle? I cannot imagine the editors set out to publish on the behalf of eccentrics like me, who are quite prepared to shell out their dough for slender (if juicy) pickings.

May 25, 2020

Hanging out with Matilda

When it comes to the Plantagenet boys, certain clichés abound. Bad King John is the wicked softsword who lost all his lands in France and ran away from every fight. Henry III is a pious mediocrity (for pious read ‘dull’) whose fifty-plus years on the throne amount to one big blur in the public imagination. Edward I is the hawkish, hard-driving Hammer of the Scots, more machine than man - yes that is a dorky Star Wars reference - and the most ideal Hollywood foil since Basil Rathbone.

"You've come to Nottingham once too often, pal."

"You've come to Nottingham once too often, pal."Clichés exist for a reason, of course, and it can be just as tiresome to play the revisionist. There is some truth in the above, but not the whole truth. Others will stand surety for John and Henry, but for my sins I chose to specialise in Longshanks. The result has been quite the study in human behaviour, in which plenty of complete strangers have felt obliged to tell me exactly what they think; not only of Edward, but the deplorable state of my personal morality and intellectual standards. I am grateful, of course.

Talking of human behaviours - and the point of this post - it may come as no surprise to discover that Edward was just as fallible as anyone else. Peel back the clichés, delve deeper into the records, and a human being emerges. In recent months I have been researching the war against France from 1294-1303, Edward’s most difficult and expensive campaign and a complete misfire according to most historians. The ‘grand flop’, as Michael Prestwich memorably put it.

Well. It wasn’t as floppy as all that, in my humble opinion. No more so than any other Angevin expedition from the days of John to Edward II, and at least Longshanks came away with a result. That’s for another time, but today I wanted to talk about his peculiar behaviour in the aftermath of the campaign.

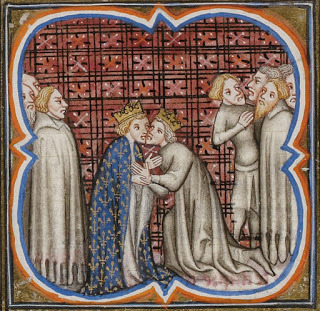

Kissing cousins...

Kissing cousins...In October 1297, after several weeks of messy to and fro, Edward struck a truce with his enemy, Philip IV of France. The ceasefire was temporary, and followed by several more rounds of talks over the following months. A final agreement was reached at Tournai in February 1298, nowadays a city in western Belgium near the French border.

It might be assumed these talks were conducted in an atmosphere of tension and barely concealed hostility. Far from it. Edward and Philip were cousins, after all, and the war was essentially a family quarrel. A Dutch eyewitness, Lodewijk van Velthem, describes the negotiations as one long round of glittering feasts and parties, in which Edward spent money like it was going out of style. He staged a particularly magnificent feast at Saint-Bavon, where nobles from all over Europe danced and drank the night away. Edward’s allies, Count Guy of Flanders and the duke of Brabant joined in the festivities, though none could rival the brilliance of Edward’s feasts.

Edward had certainly come prepared to entertain. The accounts for the Flanders expedition show he brought a well-equipped squadron of minstrels and dancers. Two were from the household of the earl of Lincoln, while one was an acrobatic dancer or saltatrix with the intriguing name of Matilda Makejoy.

It seems Edward was in no hurry to go home, to face angry barons and William Wallace raging in his fury. While the king enjoyed himself over the winter months, counter-operations against Wallace were entrusted to Earl Warenne. Rickety old Warenne hated Scotland - the weather played hell with his joints - and had already lost his dentures at Stirling Bridge. But he was the man on the spot, and had to labour on the Godforsaken northern border while Edward played tag with Mistress Makejoy.

The king’s behaviour at this time drew sharp criticism from contemporaries. Pierre Langtoft, usually an admirer, slammed Edward for:

“Idleness and feigned delay, and long morning’s sleep,

Delight in luxury, and surfeit in the evenings,

Trust in felons, compassion for enemies,

Self-will in act and counsel…”

This is all very reminiscent of Edward’s forebears. Similar charges of sloth and debauchery were aimed at grandpa John, while Henry III was nobody’s idea of a dynamic warrior-king. Yet the Angevins were a complex brood, and not so easy to pigeonhole; John and Henry were capable of astonishing bursts of energy, to the bewilderment of monkish chroniclers such as Matthew Paris. Like every good little tabloid hack, he wanted everything simple and one-dimensional. Poor Matthew: one can easily picture him sweating and cursing as he desperately struck out the offending bits from his chronicle, after Henry asked to see it.

The same behaviour patterns can be discerned in Edward, who did eventually put his dancers back in their box and return to duty. But fathers live in sons, as Philip Augustus remarks to Henry II in the Lion in Winter, and we might do well to think a little harder about these people. Because they were people, not automatons or walking clichés.

May 24, 2020

Finding Jerusalem

The Commendiato Lamentabilis in Transitu Magni Regis Edwardi is a lengthy eulogy to Edward I of England, composed shortly after his death in 1307 by John of London. John was a clerk in the service of Edward’s widowed consort, Margaret of France. His text was widely copied and distributed about England at the time, and presents a highly complex image of fourteenth-century kingship.

The text consists of a short summary or preface followed by eight lamentations, proffered respectively by the Pope, the kings of Christendom, Queen Margaret, the prelates, earls and barons, clergy, and general laity, each highlighting different aspects of royal virtue. Edward is presented as the greatest of kings, comparable to Arthur and various Biblical figures. His people, the Pope exhorted, should now grieve as Job had grieved over the loss of his sons, Abraham over the death of Sarah, Judah over the death of Josiah, and Christ over Lazarus.

Edward’s deeds in life, so often portrayed as negative or even wicked in modern times, are shown as proof of his greatness. His crusade, the conquest of Wales, the wars against the Scots and the expulsion of the Jews are all celebrated. The Commendiato is a form of propaganda, of course, but we should not fall into the trap of imagining that Edward’s contemporaries thought as we do. So far as they were concerned, his war-mongering and bigotry - as his more extreme critics might put it - were ideal traits in a king.

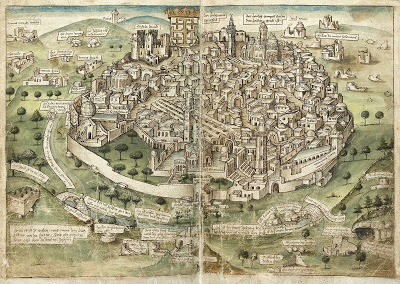

The dominant theme is Edward’s piety and desire to rescue the Holy Land. His Christian enemies, especially Philip IV of France, are condemned as enemies of holy church and worse than Saracens. Philip had, after all, prevented Edward from liberating Jerusalem. There is some basis for this hyperbole: Edward did genuinely plan to go on crusade again in 1293, but the outbreak of war with France prevented it.

A depiction of Jerusalem

A depiction of JerusalemInterestingly, the Commendiato is echoed by another eulogy for Edward, composed in Anglo-Norman. This repeats the charge against Philip and expresses the hope that, even in death, Edward’s spirit might yet find its way to the Holy Land:

“Place à Dieu en Trinité,/Que vostre fiz en pust conquere/Jerusalem la digne cite,/E passer en la seinte tere!”

The sheer length of the Commendiato is unusual for royal eulogies at this time. One comparison is the panegyric for King Wenceslas II of Bohemia (died 1305), who was praised in similar terms. He, too, was a pious king who had aggressively expanded his territory: not for reasons of mere empire-building, but because he loved justice and hated evil-doers. The peculiar emphasis on mercy and clemency, as necessary adjuncts to brutal wars of conquest, may come across as laughable hypocrisy to us. Yet these were the traits and behaviours required of successful kings.

.

May 23, 2020

Sent home to think again

In 1266, while civil war was still raging in England, a much more obscure conflict blew up on the southern borders of Gascony. This region had long been a bone of contention: the duchy of Gascony was held by the Plantagenet king-dukes of England, but the kingdoms south of the Pyrenees had their own designs on it. In 1244 Theobald ‘the Troubadour’ of Navarre had attempted to invade Gascony, but was sent packing by the English seneschal, Nicholas de Molis.

Almost twenty years later, Theobald’s successor Theobald II decided to have another go. He was handed the opportunity by Henry III’s distractions in England and Wales, though Theobald arguably left it a bit late. The ideal time to invade Gascony was in 1264-5, when Henry was Simon de Montfort’s captive. After the battle of Evesham in August 1265 Henry was a free man again, though he still had plenty of work to do in England.

Over the winter months of 1265, Theobald worked on luring the nobles of southern Gascony away from Henry’s allegiance. Many of these nobles had blood ties to the royal families of Navarre and Castile, and their loyalty to the English regime was always suspect. In December 1265 Theobald gained the homage and fealty of the Count of Comminges and the Count of Astarac. He also intrigued with the ever-troublesome Gaston VII Moncada, Viscount of Béarn. In return for supporting his claim to the county of Bigorre, Theobald persuaded Gaston to betroth his daughter Constance to the king’s brother, Henry the Fat. Henry’s nickname suggests he wasn’t exactly love’s young dream, but then Constance didn’t have much say in the matter.

In the summer of 1266, even as Henry laid siege to Kenilworth in England, the Navarrese launched their invasion. Theobald’s army laid siege to the castle of Lourdes (pictured), strategically placed to guard the seven valleys of the Lavedan in the Pyrenees. Meanwhile his partisans clashed with Henry’s supporters in the sea-port of Bayonne. The lord Arnaud-Guillaume, another Gascon noble with Navarrese connections, opened the gates of his castle of Grammont to the enemy.

The situation was rescued by the king of France, Louis IX, whose intervention forced the warring parties to agree to a truce on 19 December. Jean de Grailly, a Savoyard knight in the Lord Edward’s household, also played an important role. Jean had been permitted to settle in Gascony in 1262, and in February 1267 he negotiated a new marriage contract between Constance and Henry of Almaine, the English king’s nephew. This effectively severed Gaston de Béarn’s alliance with Navarre, and sent King Theobald home to think again.

May 18, 2020

The would-be King of Scots

"At the same time Edward took drastic steps to bring Holland back into his coalition. His first response to the defection of Count Floris had been to impose a trade embargo on Holland. In the spring he entered into a conspiracy with certain Dutch noblemen. Floris was unpopular with many of his own nobles, principally Gijsbrecht van Amstel, Hermann van Woerden and Gerard van Velzen. The Duke of Brabant, Floris’s rival for the profits of the English wool trade, was also involved. Van Velzen had some personal grudge against Floris, and within a few years rumours circulated that Floris had raped his wife. It is not possible, on the basis of currently available source evidence, to establish the truth of this accusation. However, the story was mentioned as rumour in Lodewijk van Velthelm’s continuation of Maerlants Spiegel historiael (circa 1315), and manuscript A of a Dutch rhyming chronicle, van de Rijmkroniek (circa 1330-1340).

The conspiracy against Floris was organised by Jan de Cuyck, an important envoy and diplomat in English service. Their plan was to kidnap Floris and smuggle him over to England, where he would be forced to break the alliance with Philip or resign his title to his anglophile son, John. In June 1296 Floris was captured by the conspirators while out hunting and imprisoned at Muiden castle, near Amsterdam. News quickly spread of the incident. On 27 June, when they tried to move their captive to a safer place, the conspirators were confronted by an angry mob. They panicked, stabbed Floris multiple times and left him to die in a ditch.

Edward’s involvement in the kidnapping is scarcely beyond doubt. The organiser, Jan de Cuyck, was in receipt of a payment of 200 l.t. per year from the king, and Edward stood to profit from Floris’s removal. The murder appears to have been a mistake, done on the spur of the moment, but it served Edward’s purpose just as well. He had the dead man’s son, John, in his custody, and within a few months would use him to renew the Dutch alliance."

May 15, 2020

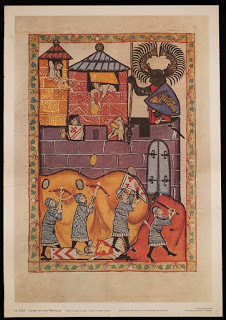

That guy's got a squint

The image is probably late 14th century, as Bar's men are wearing the style of armour from that time. In 1297 they would have worn much less plate and bucket helms instead of visored helms. As for the sabatons and gorgets and pauldrons, don't even get me started. The droit de seigneur is upside down, the jupons clash with the haketons, the grass is too green, the sky is a funny colour, and that guy fourth from the right has got a squint. Unacceptable. Up with this sort of thing I put will not.

May 14, 2020

The League of Franche-Comté (2)

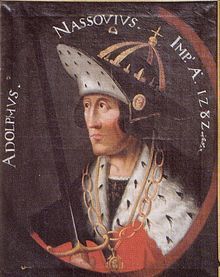

On 8 February 1297 Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany, assembled the nobles of Burgundy at Koblenz. These were Jean de Chalon-Arlay and his associates, those men who had refused to accept the count of Burgundy’s sale of his inheritance to the king of France, Philip le Bel. Instead they were loyal to the Holy Roman Empire and wished to hold their fiefs direct from Adolf.

Adolf rewarded his followers with lands taken from those Burgundians loyal to France. The count of Bar, Henri III, was given the fief of Guyot de Jonveille, and those confiscated from Jean de Bourgogne as far as Conflans in the châtellenie of Vesoul. In revenge Philip confiscated Bar’s townhouse in Paris and gave his lands in France to Charles of Valois. Tit-for-tat.

Adolf rewarded his followers with lands taken from those Burgundians loyal to France. The count of Bar, Henri III, was given the fief of Guyot de Jonveille, and those confiscated from Jean de Bourgogne as far as Conflans in the châtellenie of Vesoul. In revenge Philip confiscated Bar’s townhouse in Paris and gave his lands in France to Charles of Valois. Tit-for-tat.

Two days earlier Henri had received subsidies from his father-in-law, Edward I, brought by the bishop of Coventry and Jean de Berwick. He was therefore a key member of the Anglo-German-Burgundian alliance against the French. On 6 May, he gave to Guillaume de Remoiville, one of his vassals, the land of Maxey-sur-Vaise on the express condition that Guillaume fought the king of France.