David Pilling's Blog, page 30

March 19, 2020

The son of traitor memory (1)

Below is the first of a series of videos on the life of Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn (died 1286), lord of southern Powys and one of the great survivors of medieval Welsh history.

The son of traitor memory (1)

The son of traitor memory (1)

Published on March 19, 2020 09:29

March 16, 2020

To read and write

Could medieval kings read and write? It seems likely they could read, but writing was for clerks.

For instance in July 1282 Eleanor of Provence, the queen dowager, asked her son Edward I to listen to a draft message to the king of France and amend it if he wished. The relevant part of her message read:

“Nos avoms fet feire une letre depar vos la quele nous vo envoions et voz prioms, que vos la vuillez oir, si ele vos plest, facez la seler, et si non, voillez commander, que ele soit amendee a vestre plesir.”

(‘We have had a letter made on your behalf which we send to you, and we pray that you should wish to hear it. If it please you, have it sealed; and if not, may you wish to command that it be amended to your satisfaction’)

From this it appears that the king would listen to a letter - presumably read out by a clerk - and then order the content to be amended, if he thought it appropriate. It has been argued that kings had basic literacy, but the process of letter-writing was generally beneath them. God’s representative on earth did not lick his own postage stamps.

The earliest known example of the handwriting of a medieval English king is a code written by Edward III - ‘pater sancte’ - on letters sent to the pope in 1330 (above).

For instance in July 1282 Eleanor of Provence, the queen dowager, asked her son Edward I to listen to a draft message to the king of France and amend it if he wished. The relevant part of her message read:

“Nos avoms fet feire une letre depar vos la quele nous vo envoions et voz prioms, que vos la vuillez oir, si ele vos plest, facez la seler, et si non, voillez commander, que ele soit amendee a vestre plesir.”

(‘We have had a letter made on your behalf which we send to you, and we pray that you should wish to hear it. If it please you, have it sealed; and if not, may you wish to command that it be amended to your satisfaction’)

From this it appears that the king would listen to a letter - presumably read out by a clerk - and then order the content to be amended, if he thought it appropriate. It has been argued that kings had basic literacy, but the process of letter-writing was generally beneath them. God’s representative on earth did not lick his own postage stamps.

The earliest known example of the handwriting of a medieval English king is a code written by Edward III - ‘pater sancte’ - on letters sent to the pope in 1330 (above).

Published on March 16, 2020 05:12

March 13, 2020

The King's Welshmen

I've recently revived my Youtube channel, History Stuff, in which I talk about any historical subject that takes my fancy. Below you can view a two-part series of videos on the subject of Edward I of England (reigned 1272-1307) and his exploitation of the military resources of Wales after 1282.

The King's Welshmen (Part 1)

The King's Welshmen (Part 2)

The King's Welshmen (Part 1)

The King's Welshmen (Part 2)

Published on March 13, 2020 11:28

March 8, 2020

The royal nun

Something for International Women’s Day.

On 15 August 1285 Princess Mary, seventh daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile, was formally admitted to the priory at Amesbury. This was at least partially due to the influence of her formidable grandmother, Eleanor of Provence, who wanted to see at least one of her grandlings enter the church. Mary was six years old.

Despite being technically resident at the priory, Mary travelled quite freely and often visited court. Being a nun didn’t mean she couldn’t enjoy herself, and her father was sometimes called upon to pay her debts, even though she already received an allowance from him. The king’s affection for his daughter is shown by the regular grants of money, clothing and wine Mary received, and the highly personalised wording of these grants and concessions. In 1285 and 1289, for instance, Edward pardoned the nuns of Amesbury a year’s worth of rent expressly ‘out of love’ for his daughter.

Mary had a serious side. As the king’s daughter she wielded a deal of influence, and used it to protect religious houses and fellow clergy. In the summer of 1293 she petitioned her father - her ‘most high and most noble prince and her most dear and most beloved lord’ - asking for the return of various manors to the nuns of her community. She also upheld the community of Amesbury’s right to hold free elections, and used her influence to promote the election of favoured churchmen to various livings. The king generally conceded to her requests, even if it meant the crown lost money.

Mary died in 1332, aged about 54. She received a glowing tribute from Nicholas Trivet, the English chronicler and Dominican friar who wrote of Mary:

“And in so moche as hit ys trewly sayde of her and notably this worthy text of holy scripture: optimam partem elegit ipsi Maria, que non auferetur ab ea. The whych ys as moche to say "As Maria hathe chosyn the best party to her, the whych shall not be done away from her.”

This is apparently quite a daring adaptation of Christ’s words in the Gospel of Luke, where he good-humouredly defends Mary to her sister Martha.

On 15 August 1285 Princess Mary, seventh daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile, was formally admitted to the priory at Amesbury. This was at least partially due to the influence of her formidable grandmother, Eleanor of Provence, who wanted to see at least one of her grandlings enter the church. Mary was six years old.

Despite being technically resident at the priory, Mary travelled quite freely and often visited court. Being a nun didn’t mean she couldn’t enjoy herself, and her father was sometimes called upon to pay her debts, even though she already received an allowance from him. The king’s affection for his daughter is shown by the regular grants of money, clothing and wine Mary received, and the highly personalised wording of these grants and concessions. In 1285 and 1289, for instance, Edward pardoned the nuns of Amesbury a year’s worth of rent expressly ‘out of love’ for his daughter.

Mary had a serious side. As the king’s daughter she wielded a deal of influence, and used it to protect religious houses and fellow clergy. In the summer of 1293 she petitioned her father - her ‘most high and most noble prince and her most dear and most beloved lord’ - asking for the return of various manors to the nuns of her community. She also upheld the community of Amesbury’s right to hold free elections, and used her influence to promote the election of favoured churchmen to various livings. The king generally conceded to her requests, even if it meant the crown lost money.

Mary died in 1332, aged about 54. She received a glowing tribute from Nicholas Trivet, the English chronicler and Dominican friar who wrote of Mary:

“And in so moche as hit ys trewly sayde of her and notably this worthy text of holy scripture: optimam partem elegit ipsi Maria, que non auferetur ab ea. The whych ys as moche to say "As Maria hathe chosyn the best party to her, the whych shall not be done away from her.”

This is apparently quite a daring adaptation of Christ’s words in the Gospel of Luke, where he good-humouredly defends Mary to her sister Martha.

Published on March 08, 2020 05:33

March 3, 2020

Commonly moved to war

“The war between the Geraldines and Walter de Burgh, Earl of Ulster.”

- John Clyn’s Annals of Ireland for the year 1264

At the end of 1264 the Geraldines and de Burghs were at war. At first the conflict was limited to Connacht, where the Geraldines held prisoners in the castles of Lea and Dunamase, while Walter de Burgh attacked and seized Geraldine castles and manors.

Dunamase castleThe war quickly became more widespread. Geoffrey Geneville, justiciar of Ireland while his colleague Richard de la Rochelle was a Geraldine prisoner, prepared Dublin Castle to withstand a siege. He spent a total of £342 on improving its defences, while the royal castle at Arklow was similarly provisioned. Geneville wrote to the king, informing him that ‘the land was commonly moved to war’ and ‘there was common war in those parts’.

Dunamase castleThe war quickly became more widespread. Geoffrey Geneville, justiciar of Ireland while his colleague Richard de la Rochelle was a Geraldine prisoner, prepared Dublin Castle to withstand a siege. He spent a total of £342 on improving its defences, while the royal castle at Arklow was similarly provisioned. Geneville wrote to the king, informing him that ‘the land was commonly moved to war’ and ‘there was common war in those parts’.

The alarm of the English government is exposed in letters of 16 February 1265, which asked the archbishop of Dublin to deal with ‘the discord between the nobles and magnates of that land, whereby great danger may ensue to the king and Edward his son and the whole land of Ireland’. He was also commanded to take the king’s castles into his hand and munition them. The archbishop sent a bleak report back to London, describing the ‘great dissensions’ in Ireland.

By the late spring of 1265 the whole country was in a state of civil war. This grim situation was rescued by Geneville, who raised an army to march against the Geraldines. Geneville’s show of force persuaded the dissidents to come to terms, and in mid-April the rival parties agreed to meet at Dublin to discuss peace terms. They agreed to a set of ordinances whereby all persons ‘disseised and expelled from their lands and tenements during the aforesaid disturbances shall recover their lands and tenements without writ or plea’.

The agreement severed the alliance of the Geraldines with Simon de Montfort - the Geraldines had never been more than skin-deep allies anyway - and released the Anglo-Irish nobles of Ireland to cross the sea and join Prince Edward in time for the battle of Evesham. Geneville’s pacification of Ireland, therefore, had a direct influence on the course of the civil war in England.

- John Clyn’s Annals of Ireland for the year 1264

At the end of 1264 the Geraldines and de Burghs were at war. At first the conflict was limited to Connacht, where the Geraldines held prisoners in the castles of Lea and Dunamase, while Walter de Burgh attacked and seized Geraldine castles and manors.

Dunamase castleThe war quickly became more widespread. Geoffrey Geneville, justiciar of Ireland while his colleague Richard de la Rochelle was a Geraldine prisoner, prepared Dublin Castle to withstand a siege. He spent a total of £342 on improving its defences, while the royal castle at Arklow was similarly provisioned. Geneville wrote to the king, informing him that ‘the land was commonly moved to war’ and ‘there was common war in those parts’.

Dunamase castleThe war quickly became more widespread. Geoffrey Geneville, justiciar of Ireland while his colleague Richard de la Rochelle was a Geraldine prisoner, prepared Dublin Castle to withstand a siege. He spent a total of £342 on improving its defences, while the royal castle at Arklow was similarly provisioned. Geneville wrote to the king, informing him that ‘the land was commonly moved to war’ and ‘there was common war in those parts’.

The alarm of the English government is exposed in letters of 16 February 1265, which asked the archbishop of Dublin to deal with ‘the discord between the nobles and magnates of that land, whereby great danger may ensue to the king and Edward his son and the whole land of Ireland’. He was also commanded to take the king’s castles into his hand and munition them. The archbishop sent a bleak report back to London, describing the ‘great dissensions’ in Ireland.

By the late spring of 1265 the whole country was in a state of civil war. This grim situation was rescued by Geneville, who raised an army to march against the Geraldines. Geneville’s show of force persuaded the dissidents to come to terms, and in mid-April the rival parties agreed to meet at Dublin to discuss peace terms. They agreed to a set of ordinances whereby all persons ‘disseised and expelled from their lands and tenements during the aforesaid disturbances shall recover their lands and tenements without writ or plea’.

The agreement severed the alliance of the Geraldines with Simon de Montfort - the Geraldines had never been more than skin-deep allies anyway - and released the Anglo-Irish nobles of Ireland to cross the sea and join Prince Edward in time for the battle of Evesham. Geneville’s pacification of Ireland, therefore, had a direct influence on the course of the civil war in England.

Published on March 03, 2020 01:41

March 2, 2020

English historian and Irish historian

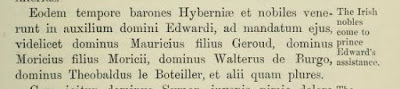

A passage from the Annals of Waverley. The entry translates as:

“At the same time barons and nobles of Ireland came to assist the Lord Edward, upon his summons, namely Sir Maurice Fitz Gerald, Sir Maurice Fitz Maurice [the leaders of the Geraldines, nephew and uncle], Sir Walter de Burgh, Sir Theobald Butler, and many others.”

This is under the year 1265 and relates to the battle of Evesham. As a direct consequence of the conflict in England, Ireland was in a state of civil war between the pro-royalist de Burgh family and the pro-Montfortian Geraldines. The seneschal, Geoffrey Geneville, skilfully pacified the Geraldines and secured the release of Richard de la Rochelle, Edward’s representative in the country. Finally he gained the support of all factions by promising they should hold their land on the same basis they had held it before the war began.

As a result of Geneville’s efforts, several important Anglo-Irish magnates crossed the Irish Sea and fought for Edward at Evesham. The Irish aspect of the Baron’s War (or whatever you want to call it) is sometimes underrated, possibly due to historians failing to take a wider view.

As Robin Frame nicely put it: “The real difficulty is revealed by those categories, “English historian” and “Irish historian”…

“At the same time barons and nobles of Ireland came to assist the Lord Edward, upon his summons, namely Sir Maurice Fitz Gerald, Sir Maurice Fitz Maurice [the leaders of the Geraldines, nephew and uncle], Sir Walter de Burgh, Sir Theobald Butler, and many others.”

This is under the year 1265 and relates to the battle of Evesham. As a direct consequence of the conflict in England, Ireland was in a state of civil war between the pro-royalist de Burgh family and the pro-Montfortian Geraldines. The seneschal, Geoffrey Geneville, skilfully pacified the Geraldines and secured the release of Richard de la Rochelle, Edward’s representative in the country. Finally he gained the support of all factions by promising they should hold their land on the same basis they had held it before the war began.

As a result of Geneville’s efforts, several important Anglo-Irish magnates crossed the Irish Sea and fought for Edward at Evesham. The Irish aspect of the Baron’s War (or whatever you want to call it) is sometimes underrated, possibly due to historians failing to take a wider view.

As Robin Frame nicely put it: “The real difficulty is revealed by those categories, “English historian” and “Irish historian”…

Published on March 02, 2020 04:07

March 1, 2020

The hard sell

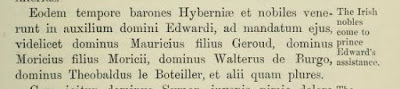

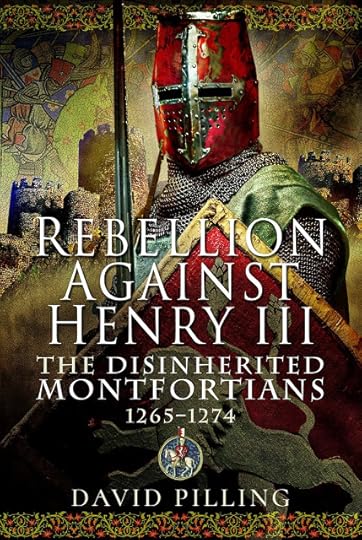

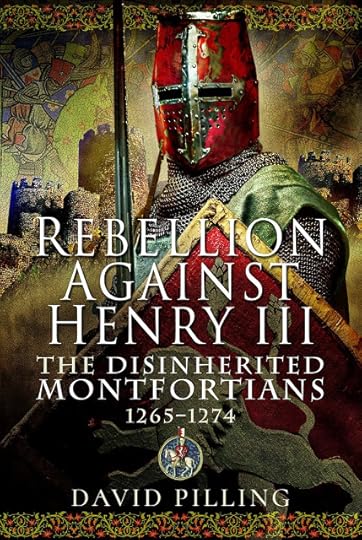

So my book will be coming out on 30 March. This is the first of a series of books of mine that will be published by Pen & Sword in the next couple of years. The theme of this one is the war of the Disinherited in England: these were Montfortian rebels who took up arms after their lands were confiscated in the wake of the battle of Evesham in 1265.

This is a bit of a neglected subject - the civil wars in England are generally supposed to have ended with Evesham, but in fact they rumbled on for another two years and related issues and conflicts kept resurfacing for decades.

I will be posting on this subject for the rest of March up to publication date. I thought it was time to actually do something with all this 'stuff', rather than post free infotainment every day

This is a bit of a neglected subject - the civil wars in England are generally supposed to have ended with Evesham, but in fact they rumbled on for another two years and related issues and conflicts kept resurfacing for decades.

I will be posting on this subject for the rest of March up to publication date. I thought it was time to actually do something with all this 'stuff', rather than post free infotainment every day

Published on March 01, 2020 03:31

February 28, 2020

Goronwy's end

Goronwy ap Heilyn is last seen at Llanberis, at the foot of Snowdon, on 2 May 1283. He was among the last cohort of supporters of Dafydd ap Gruffudd, who had assumed the title Prince of Wales after the death of his brother, Llywelyn, the previous December.

Sunset over LlanberisDafydd had wanted the crown all his life. Now it was finally in his grasp, in circumstances that resemble the last act of Macbeth. He had no soldiers left, no castles after the fall of Castell y Bere in April, and was reduced to hiding in the mountains issuing pointless charters to men who had already deserted him.

Sunset over LlanberisDafydd had wanted the crown all his life. Now it was finally in his grasp, in circumstances that resemble the last act of Macbeth. He had no soldiers left, no castles after the fall of Castell y Bere in April, and was reduced to hiding in the mountains issuing pointless charters to men who had already deserted him.

His final acts as prince occured on 2 May. On that day Gruffudd ap Maredudd, one of Dafydd’s remaining supporters, agreed to grant Cantref Penwedding to Rhys Fychan of Ceredigion. At the same time Dafydd empowered one of his officers, John son of David, to call out the men of Builth, Brecon, Maelienydd, Elfael, Gwerthyrnion and Kerry. The intention was to summon one last army and stage a final stand against the troops of Edward I as they poured into the mountain citadel.

Unknown to Dafydd, Rhys Fychan had surrendered to the king at Rhuddlan at the start of March. In exchange for his life, Rhys agreed to do military service at Aberystwyth for forty days for a fee of £16:

“Payment to Res ap Mailgun, admitted to the lord king’s wages, by order of lord W. de Valence, the lord bishop of St David’s and lord Robert Tybbetot, to guard the land of ‘Lanpader’ with 2 covered horses and 4 uncovered horses and 24 foot-soldiers, from 11 March until Monday 19 April, for 40 days, £16.”

Nobody answered Dafydd’s military summons, since the men of Maelienydd and elsewhere had already submitted to the king.

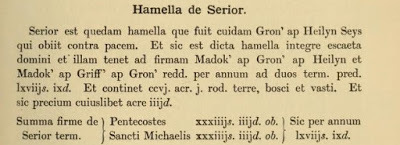

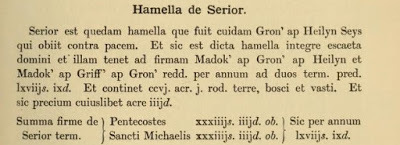

Goronwy was one of those who witnessed these two futile charters. He was killed shortly afterwards, probably in a skirmish during the final days of the invasion. All we know of his death is a brief note in the survey of the Honour of Denbigh, drawn up in 1334. This records that Goronwy ap Heilyn Sais had died ‘contra pacem’ - against the peace. The lands of his son, Madog, escheated to the crown, while another son, Llywelyn, was still in prison in 1316.

Sunset over LlanberisDafydd had wanted the crown all his life. Now it was finally in his grasp, in circumstances that resemble the last act of Macbeth. He had no soldiers left, no castles after the fall of Castell y Bere in April, and was reduced to hiding in the mountains issuing pointless charters to men who had already deserted him.

Sunset over LlanberisDafydd had wanted the crown all his life. Now it was finally in his grasp, in circumstances that resemble the last act of Macbeth. He had no soldiers left, no castles after the fall of Castell y Bere in April, and was reduced to hiding in the mountains issuing pointless charters to men who had already deserted him.His final acts as prince occured on 2 May. On that day Gruffudd ap Maredudd, one of Dafydd’s remaining supporters, agreed to grant Cantref Penwedding to Rhys Fychan of Ceredigion. At the same time Dafydd empowered one of his officers, John son of David, to call out the men of Builth, Brecon, Maelienydd, Elfael, Gwerthyrnion and Kerry. The intention was to summon one last army and stage a final stand against the troops of Edward I as they poured into the mountain citadel.

Unknown to Dafydd, Rhys Fychan had surrendered to the king at Rhuddlan at the start of March. In exchange for his life, Rhys agreed to do military service at Aberystwyth for forty days for a fee of £16:

“Payment to Res ap Mailgun, admitted to the lord king’s wages, by order of lord W. de Valence, the lord bishop of St David’s and lord Robert Tybbetot, to guard the land of ‘Lanpader’ with 2 covered horses and 4 uncovered horses and 24 foot-soldiers, from 11 March until Monday 19 April, for 40 days, £16.”

Nobody answered Dafydd’s military summons, since the men of Maelienydd and elsewhere had already submitted to the king.

Goronwy was one of those who witnessed these two futile charters. He was killed shortly afterwards, probably in a skirmish during the final days of the invasion. All we know of his death is a brief note in the survey of the Honour of Denbigh, drawn up in 1334. This records that Goronwy ap Heilyn Sais had died ‘contra pacem’ - against the peace. The lands of his son, Madog, escheated to the crown, while another son, Llywelyn, was still in prison in 1316.

Published on February 28, 2020 06:04

February 27, 2020

Seeking justice

A foot in both camps (6)

In November 1282, at Rhuddlan, the grievances of Welsh individuals and communities were laid before the king by Archbishop John Peckham. These can be found in the multi-volume printed version of his register.

As ever, it is useful to compare and contrast. Goronwy ap Heilyn, the former bailiff of Rhos and royal justice, complained that he had gone to London three times to get justice against Reynold de Grey, and not obtained it. Part of his complaint translates as follows:

“But when he believed that he would have that justice, then came Reginald de Grey, who openly said that he was entitled to take the lands by the writ of the lord king, and then seized from the said Goronwy the whole bailiwick which the lord king granted to him, and sold it as he willed. Then the said Goronwy sought justice from the lord Reginald for these oft-stated grievances, but received none.”

The protest of the community of Rhos and Englefield gives a slightly different account of Goronwy’s behaviour:

“Since he did not dare to approach the court in person, he sent a messenger with two letters, one to the lord king, and the other to his brother Llywelin, to explain to the lord king that he might lose all his lands. And the said Goronwy, because he did not carry out what he had promised them, and since the men of Rhos and Englefield were unable to obtain any justice, and since he did not wish to correct or set right those grievances, on account of this lost all his lands.”

The ‘brother Llywelin’ mentioned here is Friar Llywelyn of Bangor, who had defected to the English after being captured at sea with Eleanor de Montfort in 1275. According to the above, Goronwy was too afraid of Grey to approach the court, so he tried to get letters to the king instead. However, the men of Rhos and Englefield then accused Goronwy of failing to deliver on his promises, and even that he ‘did not wish’ to protect them.

Thanks to Rich Price for the translations.

In November 1282, at Rhuddlan, the grievances of Welsh individuals and communities were laid before the king by Archbishop John Peckham. These can be found in the multi-volume printed version of his register.

As ever, it is useful to compare and contrast. Goronwy ap Heilyn, the former bailiff of Rhos and royal justice, complained that he had gone to London three times to get justice against Reynold de Grey, and not obtained it. Part of his complaint translates as follows:

“But when he believed that he would have that justice, then came Reginald de Grey, who openly said that he was entitled to take the lands by the writ of the lord king, and then seized from the said Goronwy the whole bailiwick which the lord king granted to him, and sold it as he willed. Then the said Goronwy sought justice from the lord Reginald for these oft-stated grievances, but received none.”

The protest of the community of Rhos and Englefield gives a slightly different account of Goronwy’s behaviour:

“Since he did not dare to approach the court in person, he sent a messenger with two letters, one to the lord king, and the other to his brother Llywelin, to explain to the lord king that he might lose all his lands. And the said Goronwy, because he did not carry out what he had promised them, and since the men of Rhos and Englefield were unable to obtain any justice, and since he did not wish to correct or set right those grievances, on account of this lost all his lands.”

The ‘brother Llywelin’ mentioned here is Friar Llywelyn of Bangor, who had defected to the English after being captured at sea with Eleanor de Montfort in 1275. According to the above, Goronwy was too afraid of Grey to approach the court, so he tried to get letters to the king instead. However, the men of Rhos and Englefield then accused Goronwy of failing to deliver on his promises, and even that he ‘did not wish’ to protect them.

Thanks to Rich Price for the translations.

Published on February 27, 2020 01:08

February 25, 2020

An utter thug

The war of Reynold de Grey (2)

Lord Reynold de Grey, who made himself so hated in North Wales, was an equal-opportunities oppressor. Apart from abusing the communities of Rhos and Englefield, he also found time to wage war on his fellow Marcher lords.

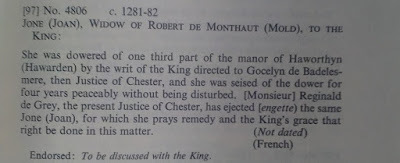

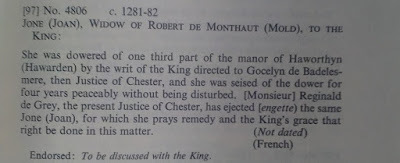

In the mid-1270s the castle of Ewloe (second pic) built by the princes of Gwynedd, passed into the hands of Robert de Monthaut. After his death the land and tenements passed to his widow, Joan. She enjoyed them for four years until Grey threw her out and seized the manor for himself. When her son Roger came of age, he tried to sue Grey in court, but died while the case was in progress. Grey held onto Ewloe until his death, and it was finally restored to the Monthauts by Queen Isabella in 1327.

Lord Grey was an utter thug, whose aim in life was to steal as much land as possible and kill anyone who tried to stop him. He actually said as much to Earl Warenne, when the two came to blows in 1287. He was also a brilliant military captain: born into a later age, he would have given Quantrill’s Raiders the fright of their lives. In 1267 Grey’s light cavalry slaughtered the March riders of Earl Gilbert de Clare outside London, and a couple of years later crushed an army of outlaws in the northern counties. His skill at guerilla warfare made him indispensable in Wales, and he was among the four big ‘batailles’ of English heavy cavalry at Falkirk. Such men were too useful to throw away.

Grey’s great-great grandson, Baron Grey of Ruthin, was the chap who triggered the revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr. The third pic is an illustration of the Grey arms, taken from The Grey Hours, a book of hours made for the family and dated c.1390.

Lord Reynold de Grey, who made himself so hated in North Wales, was an equal-opportunities oppressor. Apart from abusing the communities of Rhos and Englefield, he also found time to wage war on his fellow Marcher lords.

In the mid-1270s the castle of Ewloe (second pic) built by the princes of Gwynedd, passed into the hands of Robert de Monthaut. After his death the land and tenements passed to his widow, Joan. She enjoyed them for four years until Grey threw her out and seized the manor for himself. When her son Roger came of age, he tried to sue Grey in court, but died while the case was in progress. Grey held onto Ewloe until his death, and it was finally restored to the Monthauts by Queen Isabella in 1327.

Lord Grey was an utter thug, whose aim in life was to steal as much land as possible and kill anyone who tried to stop him. He actually said as much to Earl Warenne, when the two came to blows in 1287. He was also a brilliant military captain: born into a later age, he would have given Quantrill’s Raiders the fright of their lives. In 1267 Grey’s light cavalry slaughtered the March riders of Earl Gilbert de Clare outside London, and a couple of years later crushed an army of outlaws in the northern counties. His skill at guerilla warfare made him indispensable in Wales, and he was among the four big ‘batailles’ of English heavy cavalry at Falkirk. Such men were too useful to throw away.

Grey’s great-great grandson, Baron Grey of Ruthin, was the chap who triggered the revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr. The third pic is an illustration of the Grey arms, taken from The Grey Hours, a book of hours made for the family and dated c.1390.

Published on February 25, 2020 04:31