David Pilling's Blog, page 33

January 30, 2020

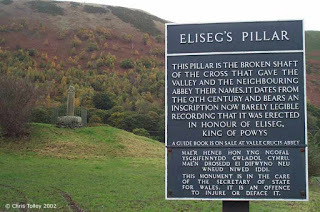

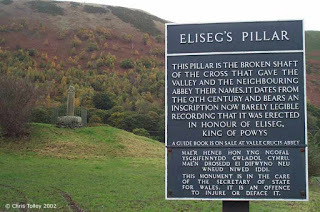

The Pillar of Eliseg

Castell Dinas Bran, high above the Dee valley near Llangollen. One of the earliest notices of the castle is in December 1270, when the heirs of Gruffudd ap Madog confirmed grants that their father had made to his wife, Emma Audley. The deed is dated at Dinas Bran, which means that enough of a structure must have existed by then; otherwise the family would have gathered on an exposed hilltop, which seems unlikely.

The reasons for building a stone castle on this lofty perch were twofold. It overlooked the dynastic abbey of Valle Crucis and the pillar or cross of Eliseg, suggesting the lords of Powys Fadog regarded this area as the cradle of their dynasty. Second, the castle shows traces of design influences from Gwynedd, and may have been intended as part of a defensive cordon of strongholds devised by Prince Llywelyn. These also included Ewloe, Dolforwyn, Bryn Amlwg and Rhyd y Briw. The D-tower at Dinas Bran is typical of the design of castles of the princes of Gwynedd.

Gruffudd had died in 1269. Hailed as “potens et prudens” - powerful and discreet - by chroniclers, his loss was a severe blow to Prince Llywelyn, who had already lost another valued advisor, Goronwy ab Ednyfed, in the previous year. The death of these men in quick succession may have been key to Llywelyn’s downfall, since his fortunes declined from 1269 onward.

Following the death of Gruffudd, his lordship was divided among four of his sons. Prince Llywelyn gave Maelor Gymraeg and Maelor Saesneg to Madog, and half of Glyndyfrdwy. Llywelyn Fychan, the Dragon of Chirk, got Nanheudwy, part of Cynllaith, part of Mochnant and Carreghofa. Gruffydd Fychan, a direct ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, got part of Glyndyfrdwy and Ial, while Owain got Bangor Is Coed and another part of Cynllaith. Madog’s primacy among the brothers is shown in the record of the trial of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn in 1274, where Madog witnessed the main record of the trial.

The reasons for building a stone castle on this lofty perch were twofold. It overlooked the dynastic abbey of Valle Crucis and the pillar or cross of Eliseg, suggesting the lords of Powys Fadog regarded this area as the cradle of their dynasty. Second, the castle shows traces of design influences from Gwynedd, and may have been intended as part of a defensive cordon of strongholds devised by Prince Llywelyn. These also included Ewloe, Dolforwyn, Bryn Amlwg and Rhyd y Briw. The D-tower at Dinas Bran is typical of the design of castles of the princes of Gwynedd.

Gruffudd had died in 1269. Hailed as “potens et prudens” - powerful and discreet - by chroniclers, his loss was a severe blow to Prince Llywelyn, who had already lost another valued advisor, Goronwy ab Ednyfed, in the previous year. The death of these men in quick succession may have been key to Llywelyn’s downfall, since his fortunes declined from 1269 onward.

Following the death of Gruffudd, his lordship was divided among four of his sons. Prince Llywelyn gave Maelor Gymraeg and Maelor Saesneg to Madog, and half of Glyndyfrdwy. Llywelyn Fychan, the Dragon of Chirk, got Nanheudwy, part of Cynllaith, part of Mochnant and Carreghofa. Gruffydd Fychan, a direct ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, got part of Glyndyfrdwy and Ial, while Owain got Bangor Is Coed and another part of Cynllaith. Madog’s primacy among the brothers is shown in the record of the trial of Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn in 1274, where Madog witnessed the main record of the trial.

Published on January 30, 2020 04:17

January 29, 2020

Elderly Welsh harpists

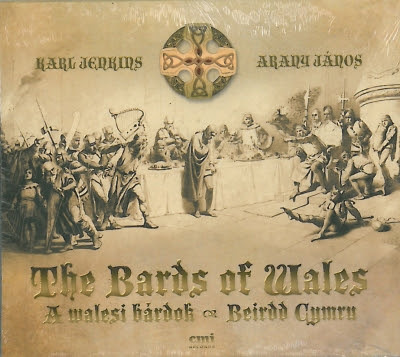

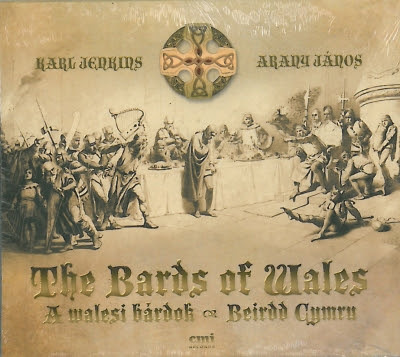

“The historians doubt it, but it strongly stands in the legend that Edward I of England sent 500 Welsh bards to the stake after his victory over the Welsh (1277) to prevent them from arousing the country and destroying English rule by telling of the glorious past of their nation.” -

Janos Anary, the Hungarian poet who wrote The Bards of Wales (A walesi wárdok).

In this famous poem, composed in 1857, Edward Longshanks has a gigantic hissy fit and orders all the bards in Wales to be burnt at the stake. The poem was really meant as an analogy for Hapsburg control of Hungary and the repressive policies of Alexander von Bach, but the legend of flash-fried Welsh bards still finds the occasional echo today.

If any bard of Edward’s day was lined up for the stake, that man was surely Llygad Gwr. Llygad had been the court poet of Gruffudd ap Madog, whom the king must have regarded as a traitor; Gruffudd spent decades in English service before arranging the slaughter of Edward’s soldiers at Cymerau and defecting to Prince Llywelyn. Llygad also composed praise songs for Llywelyn, reckoned the most ‘nationalist’ poetry in Wales before the days of Owain Glyn Dwr.

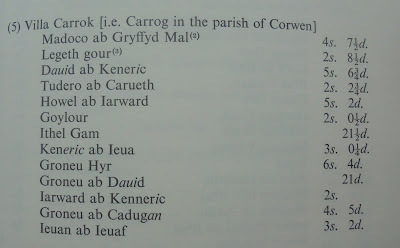

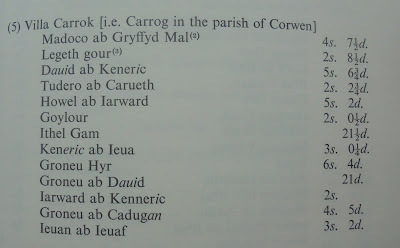

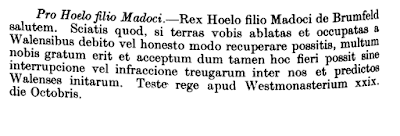

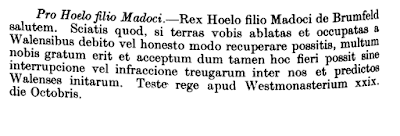

Even so, it seems the wicked tyrant had bigger fish to fry than an elderly Welsh harpist. Surviving tax rolls (attached) show that Llygad Gwyr - “Legeth gour”, in the clumsy spelling of an English clerk - was alive and well in the vill of Carrog in the parish of Corwen in 1291. This makes sense, since Corwen lay inside the territory of Edeirnion, once held by Llygad’s old master Gruffudd ap Madog.

The record shows that Llygad, who must have been a very old man by 1291, paid 2 shillings 8.5 pence in tax: a good example of the excruciating attention to detail of the new royal administration in Wales. As such he was the second highest taxpayer in the vill after Madog ab Gruffydd Mal. This man could possibly be identified as Madog Grupl, Glyn Dwr’s great-grandfather.

Thus it seems that King Ted preferred to charge the bards of Wales VAT rather than chase them with a packet of firelighters. Within three generations Welsh poets such as Iolo Goch were composing praise poems to Edward’s descendents. For money, of course; what goes round comes round.

Janos Anary, the Hungarian poet who wrote The Bards of Wales (A walesi wárdok).

In this famous poem, composed in 1857, Edward Longshanks has a gigantic hissy fit and orders all the bards in Wales to be burnt at the stake. The poem was really meant as an analogy for Hapsburg control of Hungary and the repressive policies of Alexander von Bach, but the legend of flash-fried Welsh bards still finds the occasional echo today.

If any bard of Edward’s day was lined up for the stake, that man was surely Llygad Gwr. Llygad had been the court poet of Gruffudd ap Madog, whom the king must have regarded as a traitor; Gruffudd spent decades in English service before arranging the slaughter of Edward’s soldiers at Cymerau and defecting to Prince Llywelyn. Llygad also composed praise songs for Llywelyn, reckoned the most ‘nationalist’ poetry in Wales before the days of Owain Glyn Dwr.

Even so, it seems the wicked tyrant had bigger fish to fry than an elderly Welsh harpist. Surviving tax rolls (attached) show that Llygad Gwyr - “Legeth gour”, in the clumsy spelling of an English clerk - was alive and well in the vill of Carrog in the parish of Corwen in 1291. This makes sense, since Corwen lay inside the territory of Edeirnion, once held by Llygad’s old master Gruffudd ap Madog.

The record shows that Llygad, who must have been a very old man by 1291, paid 2 shillings 8.5 pence in tax: a good example of the excruciating attention to detail of the new royal administration in Wales. As such he was the second highest taxpayer in the vill after Madog ab Gruffydd Mal. This man could possibly be identified as Madog Grupl, Glyn Dwr’s great-grandfather.

Thus it seems that King Ted preferred to charge the bards of Wales VAT rather than chase them with a packet of firelighters. Within three generations Welsh poets such as Iolo Goch were composing praise poems to Edward’s descendents. For money, of course; what goes round comes round.

Published on January 29, 2020 06:13

The crowned one of Mathrafal

The closeness of the relationship between Gruffudd ap Madog and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was made apparent in 1258, when Llywelyn proposed to marry his sister Margaret to his new ally. Gruffudd also took the opportunity to seize those lands in Powys that had been held by his brothers, especially those of Hywel. Consequently Hywel ap Madog remained loyal to the English and received cash gifts from Henry III. In October Henry wrote to Hywel condoning his efforts to recover his lost lands, but warned him not to disturb the truce that existed between the king and the Welsh. Quite how Hywel was supposed to take back his lands without disturbing the peace is unclear, but he was doubtless grateful for the money.

The parity or partnership with equals between Llywelyn and Gruffudd could not last long. Llywelyn first assumed the title Prince of Wales in March 1258, in an agreement between Scottish and Welsh lords in which Gruffudd was named third in the list of Welsh rulers, after Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd. A man who would be king (or prince) could have no equals, and Gruffudd found himself slowly relegated to the B-list.

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:

“Gruffudd…a ddalio Powys” (may Gruffudd hold Powys)

“Ohonawd henyw dadanudd” (the recovery of a patrimony springs from you)

In a slightly later poem, Llygad changes his tune somewhat and praises Llywelyn as supreme in Gwynedd and the war-leader active from Pulford to Cydweli. He is also praised as the “crowned one of Mathrafal”. Mathrafal, at least as far as Gwynedd jurists were concerned, was the chief court of Powys.

Llywelyn’s influence in Powys was also demonstrated by his agreement with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn in December 1263. Among the lands Llywelyn restored to Gruffudd was Deuddwr, part of Y Tair Swydd. Deuddwr had been a bone of contention between Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog, and Llywelyn chose to award it to the former.

[The grassy bump in the ground is all that remains of Mathrafal castle]

The parity or partnership with equals between Llywelyn and Gruffudd could not last long. Llywelyn first assumed the title Prince of Wales in March 1258, in an agreement between Scottish and Welsh lords in which Gruffudd was named third in the list of Welsh rulers, after Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd. A man who would be king (or prince) could have no equals, and Gruffudd found himself slowly relegated to the B-list.

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:

The fragile nature of Gruffudd’s relationship with Llywelyn is implied in the poetry of Llygad Gwr. In 1258, Llygad emphasised Gruffudd’s rightful lordship over Powys:“Gruffudd…a ddalio Powys” (may Gruffudd hold Powys)

“Ohonawd henyw dadanudd” (the recovery of a patrimony springs from you)

In a slightly later poem, Llygad changes his tune somewhat and praises Llywelyn as supreme in Gwynedd and the war-leader active from Pulford to Cydweli. He is also praised as the “crowned one of Mathrafal”. Mathrafal, at least as far as Gwynedd jurists were concerned, was the chief court of Powys.

Llywelyn’s influence in Powys was also demonstrated by his agreement with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn in December 1263. Among the lands Llywelyn restored to Gruffudd was Deuddwr, part of Y Tair Swydd. Deuddwr had been a bone of contention between Gwenwynwyn and Gruffudd ap Madog, and Llywelyn chose to award it to the former.

[The grassy bump in the ground is all that remains of Mathrafal castle]

Published on January 29, 2020 01:12

January 28, 2020

Playing a double game

On 2 June 1257 an English army under the leadership of Stephen Bauzan was destroyed at Cymerau in southwest Wales. The potential role of Gruffudd ap Madog, lord of Bromfield, in achieving this victory is often ignored.

Up until very recently Gruffudd had been a crown loyalist. He appears to have despised Llywelyn the Great and his successor, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, on account of their ill-treatment of Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffudd. After Gruffudd’s fatal plunge from the Tower or London, Gruffudd ap Madog’s attitude slowly changed.

In the early summer of 1257 Gruffudd apparently remained on active on behalf of Henry III. Along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, he was ordered by the king to assist John de Grey in the defence of the marchlands. Gruffudd ap Madog took charge of the border lordship of Kinnerley from his brother-in-law James Audley. He was only able to hold it for a month before being driven out by the invasion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In June, very shortly before the English defeat at Cymerau, Gruffudd was still receiving grants of English territory in the midlands as compensation for his losses.

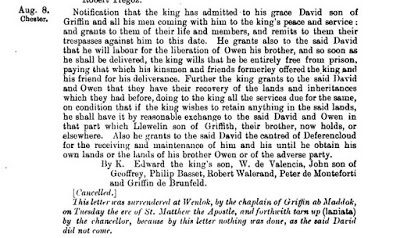

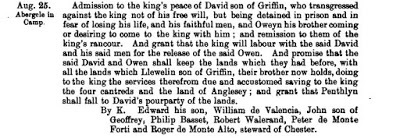

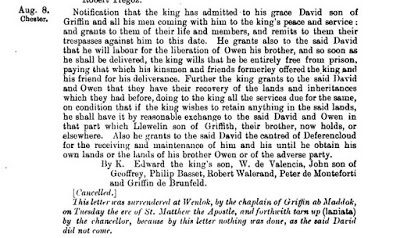

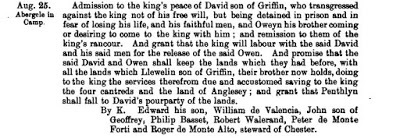

Matthew Paris wrote that the victory of Cymerau was achieved ‘by the advice and instruction’ of Gruffudd ap Madog. Paris cannot be trusted, but had clearly heard a story of Gruffudd playing a double game. Some suggestive evidence can be found in Henry III’s correspondence. On 8 August the king made arrangements to receive Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn’s brother, whom Henry believed was about to defect to his side. One of the witnesses on this letter is Gruffudd ap Madog. He was clearly party to this plan. Another letter to this effect was issued on 25 August.

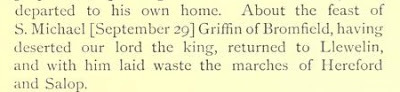

Gruffudd’s name does not appear on this second letter. On 20 September his chaplain was ordered to tear up both letters, since Dafydd had not come to the king. Just over a week later, according to the Annals of Chester, Gruffudd defected to Prince Llywelyn.

Up until very recently Gruffudd had been a crown loyalist. He appears to have despised Llywelyn the Great and his successor, Dafydd ap Llywelyn, on account of their ill-treatment of Llywelyn’s eldest son Gruffudd. After Gruffudd’s fatal plunge from the Tower or London, Gruffudd ap Madog’s attitude slowly changed.

In the early summer of 1257 Gruffudd apparently remained on active on behalf of Henry III. Along with Gruffudd ap Gwenwynwyn, lord of southern Powys, he was ordered by the king to assist John de Grey in the defence of the marchlands. Gruffudd ap Madog took charge of the border lordship of Kinnerley from his brother-in-law James Audley. He was only able to hold it for a month before being driven out by the invasion of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. In June, very shortly before the English defeat at Cymerau, Gruffudd was still receiving grants of English territory in the midlands as compensation for his losses.

Matthew Paris wrote that the victory of Cymerau was achieved ‘by the advice and instruction’ of Gruffudd ap Madog. Paris cannot be trusted, but had clearly heard a story of Gruffudd playing a double game. Some suggestive evidence can be found in Henry III’s correspondence. On 8 August the king made arrangements to receive Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn’s brother, whom Henry believed was about to defect to his side. One of the witnesses on this letter is Gruffudd ap Madog. He was clearly party to this plan. Another letter to this effect was issued on 25 August.

Gruffudd’s name does not appear on this second letter. On 20 September his chaplain was ordered to tear up both letters, since Dafydd had not come to the king. Just over a week later, according to the Annals of Chester, Gruffudd defected to Prince Llywelyn.

Published on January 28, 2020 05:25

January 27, 2020

An expression of incoherence

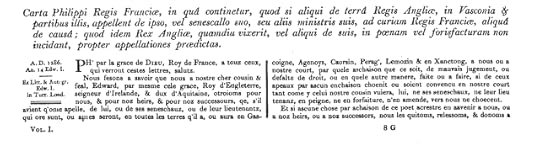

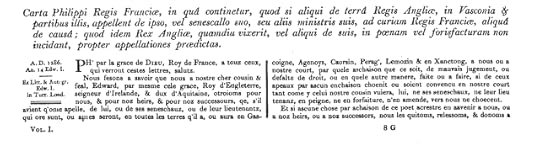

The peace of Amiens (3)

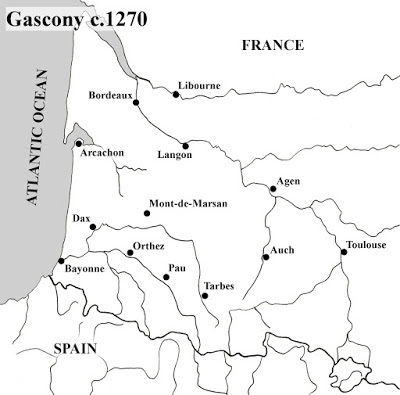

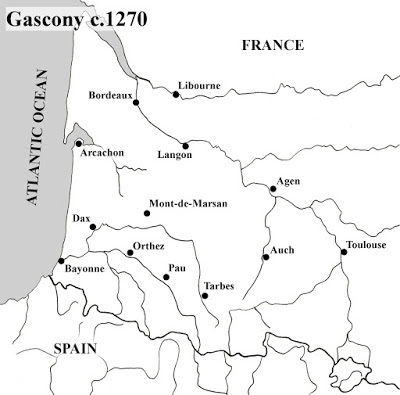

The third territory to be recovered by the English via the Treaty of Amiens in 1279 was the Agenais. This lay south of Périgord and in ancient Gaul was known as the country of the Nitiobriges, with Aginnum for their capital; in the fourth century AD it was part of the Roman province of Aquitaina Secunda and formed the diocese of Agen.

The city of Agen

The city of Agen

In 1152 the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II brought Agen into the vast family conglomerate known to later generations as the Angevin Empire. In 1212, during the Albigensian crusade, Simon de Montfort senior captured Penne-d’Agenais and burnt heretics at the stake. Via the Treaty of Paris in 1259 King Louis of France agreed to pay rent to Henry III of England for Agen, but in 1271 it should have passed to the English crown after the death of Joan of Poitiers. Instead the French hung on to it, as they did the Saintonge and other territories.

Edward I set about prising his rights from the grasp of Philip III, Louis’s successor. Philip was amenable and in August 1279 agreed to transfer Agen to the English. The transfer from one jurisdiction to another was a complex process. It began immediately after the treaty of Amiens was sealed (May 1279) and the task was entrusted to Edward’s uncle, William de Valence. The actual details were worked out by Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, and the bishop of Agen. On 9 August the proctors of the two kings met in the cloister of Agen in the presence of local clergy and lords, and representatives of the towns, the counts of Armagnac and Bigorre and other Gascon lords.

The Garonne river

The Garonne river

Here the transfer was announced. The seneschal of the king of France formally stripped himself of his duties and handed over to the English the revenues of the Agenais accrued since the date of the treaty (23 May). There was a slight hiccup when it was announced that a Gascon, the lord of Bergerac, would be the new seneschal. He was not a popular man, so Grailly smoothed things over by taking on the post himself for the time being.

The recovery of the Agenais gave Edward control of the Garonne, on which the city of Agen lies, and of its northern tributary, the Lot. Périgord lay to the north, the combined fiefs of Armagnac and Fezenac (held of Edward as duke of Aquitaine) to the south. It was a land of interlocking jurisdictions, described by the Anglo-French historian G.P. Cuttino as ‘an expression of incoherence’.

The third territory to be recovered by the English via the Treaty of Amiens in 1279 was the Agenais. This lay south of Périgord and in ancient Gaul was known as the country of the Nitiobriges, with Aginnum for their capital; in the fourth century AD it was part of the Roman province of Aquitaina Secunda and formed the diocese of Agen.

The city of Agen

The city of AgenIn 1152 the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II brought Agen into the vast family conglomerate known to later generations as the Angevin Empire. In 1212, during the Albigensian crusade, Simon de Montfort senior captured Penne-d’Agenais and burnt heretics at the stake. Via the Treaty of Paris in 1259 King Louis of France agreed to pay rent to Henry III of England for Agen, but in 1271 it should have passed to the English crown after the death of Joan of Poitiers. Instead the French hung on to it, as they did the Saintonge and other territories.

Edward I set about prising his rights from the grasp of Philip III, Louis’s successor. Philip was amenable and in August 1279 agreed to transfer Agen to the English. The transfer from one jurisdiction to another was a complex process. It began immediately after the treaty of Amiens was sealed (May 1279) and the task was entrusted to Edward’s uncle, William de Valence. The actual details were worked out by Jean de Grailly, seneschal of Gascony, and the bishop of Agen. On 9 August the proctors of the two kings met in the cloister of Agen in the presence of local clergy and lords, and representatives of the towns, the counts of Armagnac and Bigorre and other Gascon lords.

The Garonne river

The Garonne riverHere the transfer was announced. The seneschal of the king of France formally stripped himself of his duties and handed over to the English the revenues of the Agenais accrued since the date of the treaty (23 May). There was a slight hiccup when it was announced that a Gascon, the lord of Bergerac, would be the new seneschal. He was not a popular man, so Grailly smoothed things over by taking on the post himself for the time being.

The recovery of the Agenais gave Edward control of the Garonne, on which the city of Agen lies, and of its northern tributary, the Lot. Périgord lay to the north, the combined fiefs of Armagnac and Fezenac (held of Edward as duke of Aquitaine) to the south. It was a land of interlocking jurisdictions, described by the Anglo-French historian G.P. Cuttino as ‘an expression of incoherence’.

Published on January 27, 2020 06:36

January 26, 2020

The bridge over Saintonge

The peace of Amiens (2)

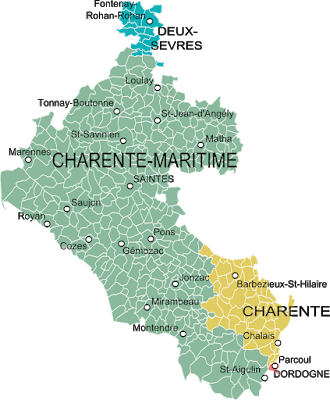

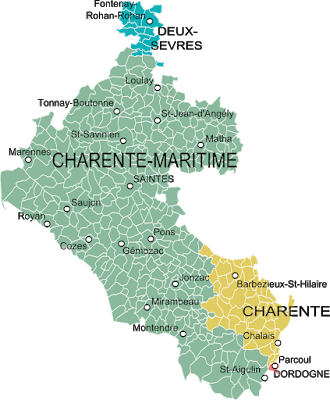

Saintonge, on the west central Atlantic coast of France, was another territory that ought to have ceded to the English via the Treaty of Paris. In August 1279, after the talks at Amiens, Philip III agreed to relinquish part of Saintonge to Edward I. This involved the recognition of Edward’s lordship over all the lands which Alphonse of Poitiers and his heirs had held south of the river Charente.

Philip’s nobles didn’t like to see their king making so many concessions. Two years later the parlement at Paris tried to get out of the deal, by ruling that any fiefs south of the Charente held of lords on the French side of the river should owe homage to their chief lord, rather than the king of England. This ruling appears to have been ignored or quietly put aside, and Edward continued to hold the territory until 1294.

Trouble started in 1293. The treaty of Amiens effectively cut Saintonge in two, with the English in control of the left side of the river and the French the right. The nominal capital on the English side was Saintes, seat of the former comital power, where Edward’s seneschal Rostand de Soler ruled in the king’s name.

The Saintes bridge over the Charente literally divided it into an English and a French town. This division was important, since it allowed Norman pirates to attack the English side and then use the French side as a safe haven. The Charente river was one of the primary locations for picking up wine to be taken north, and so an ideal target for piracy.

Charles of Valois

Charles of Valois

In a surviving report submitted by Rostand to Edward in 1293, the seneschal describes a campaign of terror waged by Norman pirates against English-held Saintonge:

“Armed with crossbows, swords, falchions and lances, and clad in haketons and bascinets, they entered the Charente river and soon started wreaking havoc.”

English chroniclers accused Philip le Bel’s brother, Charles of Valois, of deliberately egging on the pirates to provoke a war between England and France. The Chronicle of Lanercost even alleged that he desired to replace his brother as king of France, and hated the English because Edward supported Philip.

Saintonge, on the west central Atlantic coast of France, was another territory that ought to have ceded to the English via the Treaty of Paris. In August 1279, after the talks at Amiens, Philip III agreed to relinquish part of Saintonge to Edward I. This involved the recognition of Edward’s lordship over all the lands which Alphonse of Poitiers and his heirs had held south of the river Charente.

Philip’s nobles didn’t like to see their king making so many concessions. Two years later the parlement at Paris tried to get out of the deal, by ruling that any fiefs south of the Charente held of lords on the French side of the river should owe homage to their chief lord, rather than the king of England. This ruling appears to have been ignored or quietly put aside, and Edward continued to hold the territory until 1294.

Trouble started in 1293. The treaty of Amiens effectively cut Saintonge in two, with the English in control of the left side of the river and the French the right. The nominal capital on the English side was Saintes, seat of the former comital power, where Edward’s seneschal Rostand de Soler ruled in the king’s name.

The Saintes bridge over the Charente literally divided it into an English and a French town. This division was important, since it allowed Norman pirates to attack the English side and then use the French side as a safe haven. The Charente river was one of the primary locations for picking up wine to be taken north, and so an ideal target for piracy.

Charles of Valois

Charles of ValoisIn a surviving report submitted by Rostand to Edward in 1293, the seneschal describes a campaign of terror waged by Norman pirates against English-held Saintonge:

“Armed with crossbows, swords, falchions and lances, and clad in haketons and bascinets, they entered the Charente river and soon started wreaking havoc.”

English chroniclers accused Philip le Bel’s brother, Charles of Valois, of deliberately egging on the pirates to provoke a war between England and France. The Chronicle of Lanercost even alleged that he desired to replace his brother as king of France, and hated the English because Edward supported Philip.

Published on January 26, 2020 01:50

January 25, 2020

Powicke on Henry

Maurice Powicke on Henry III:

“In spite of his faults he was never corrupted. If the child was father to the man, he was an inquisitive boy, observant of men and things about him, appreciative of beauty and form, especially in jewel and metal-work, attentive to detail in apparel, decoration, and ceremonial. He was affecionate and trustful by nature, but impulsive, easily distracted, and hot-tempered. His suspicion, his brooding memory of injuries long after they were generally forgotten, like his grateful reliance upon the few whom he felt he could really trust, may well have been fostered by his experiences as a boy in a court disturbed by the cross-currents of jealousy, faction, and ambition. He was easily frightened and disposed to swing violently from one side to another. He was not generous, though he was lavish; he was poor in judgement, though quick in perception; he was not magnaminous, though he could be dignified and decorous; he was devout rather than spiritually minded. Yet, when all has been said, Henry remains a decent man, and, in his way, a man to be reckoned with. He got through all his troubles and left England more prosperous, more united, more beautiful than it was when he was a child.”

- The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307

Whether one agrees with any or all of the above, Powicke’s description of Henry is full of nuances, which in turn stimulates thought (or should). Good for Powicke, say I.

“In spite of his faults he was never corrupted. If the child was father to the man, he was an inquisitive boy, observant of men and things about him, appreciative of beauty and form, especially in jewel and metal-work, attentive to detail in apparel, decoration, and ceremonial. He was affecionate and trustful by nature, but impulsive, easily distracted, and hot-tempered. His suspicion, his brooding memory of injuries long after they were generally forgotten, like his grateful reliance upon the few whom he felt he could really trust, may well have been fostered by his experiences as a boy in a court disturbed by the cross-currents of jealousy, faction, and ambition. He was easily frightened and disposed to swing violently from one side to another. He was not generous, though he was lavish; he was poor in judgement, though quick in perception; he was not magnaminous, though he could be dignified and decorous; he was devout rather than spiritually minded. Yet, when all has been said, Henry remains a decent man, and, in his way, a man to be reckoned with. He got through all his troubles and left England more prosperous, more united, more beautiful than it was when he was a child.”

- The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307

Whether one agrees with any or all of the above, Powicke’s description of Henry is full of nuances, which in turn stimulates thought (or should). Good for Powicke, say I.

Published on January 25, 2020 06:38

January 24, 2020

Peace and settlement

The peace of Amiens (1)

On 23 May 1279 two kings, Philip III of France and Edward I of England, met at Amiens to discuss the settlement of the English king’s rights. Via the treaty of Paris in 1259, Edward was owed certain lands in France after the death of Alphonse of Poitiers and his wife, Joan. Alphonse and Joan had died within days of each other in 1271, but the French had held onto the outstanding territories.

Among Edward’s claims were the three dioceses of Limoges, Perigueux and Quercy. Limoges was a particular bone of contention, and had triggered the brief conflict in the Limousin I described in previous posts. That ended with Edward having to pay war damages to Philip.

Philip III

Philip III

In the new agreement at Amiens, Edward abandoned his claims to the three dioceses, so long as he could retain the fealty of those inhabitants who wished to remain vassals of the English crown. This was in order to keep his promise, made in 1274, not to abandon the bourgoise of Limoges. Those who maintained their fealty to Edward were called the privileged or ‘privilegiati’.

Philip, in his turn, agreed to waive one of the most troublesome conditions of the treaty of Paris. This was an obligation placed upon Edward, as duke of Aquitaine, to extract from his vassals in France an oath to the king of France that they would oppose the duke if he failed to uphold the treaty. In other words, Edward was obliged to make his own subjects agree to fight him on behalf of the French. He used persuasion, threats and intimidation to get them to swear this oath, but they refused. Finally, at Amiens, Philip agreed to drop this absurd clause and let it lie.

The issue was not finally settled until 1286 when Philip’s successor, Philip le Bel, confirmed Edward’s lordship over the privileged of the three dioceses. Thus all was settled amicably and with gain on both sides; a typically subtle political arrangement of the time. Don’t expect it to appear on Netflix anytime soon.

On 23 May 1279 two kings, Philip III of France and Edward I of England, met at Amiens to discuss the settlement of the English king’s rights. Via the treaty of Paris in 1259, Edward was owed certain lands in France after the death of Alphonse of Poitiers and his wife, Joan. Alphonse and Joan had died within days of each other in 1271, but the French had held onto the outstanding territories.

Among Edward’s claims were the three dioceses of Limoges, Perigueux and Quercy. Limoges was a particular bone of contention, and had triggered the brief conflict in the Limousin I described in previous posts. That ended with Edward having to pay war damages to Philip.

Philip III

Philip IIIIn the new agreement at Amiens, Edward abandoned his claims to the three dioceses, so long as he could retain the fealty of those inhabitants who wished to remain vassals of the English crown. This was in order to keep his promise, made in 1274, not to abandon the bourgoise of Limoges. Those who maintained their fealty to Edward were called the privileged or ‘privilegiati’.

Philip, in his turn, agreed to waive one of the most troublesome conditions of the treaty of Paris. This was an obligation placed upon Edward, as duke of Aquitaine, to extract from his vassals in France an oath to the king of France that they would oppose the duke if he failed to uphold the treaty. In other words, Edward was obliged to make his own subjects agree to fight him on behalf of the French. He used persuasion, threats and intimidation to get them to swear this oath, but they refused. Finally, at Amiens, Philip agreed to drop this absurd clause and let it lie.

The issue was not finally settled until 1286 when Philip’s successor, Philip le Bel, confirmed Edward’s lordship over the privileged of the three dioceses. Thus all was settled amicably and with gain on both sides; a typically subtle political arrangement of the time. Don’t expect it to appear on Netflix anytime soon.

Published on January 24, 2020 05:23

January 23, 2020

The Two Eleanors

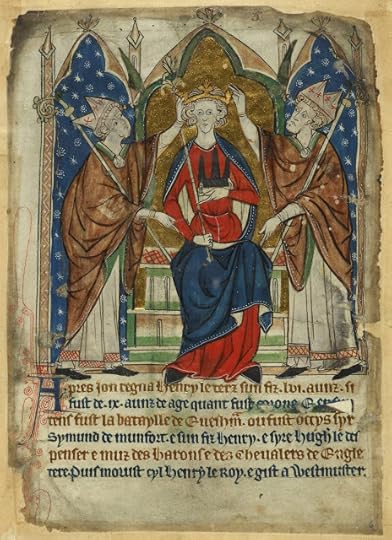

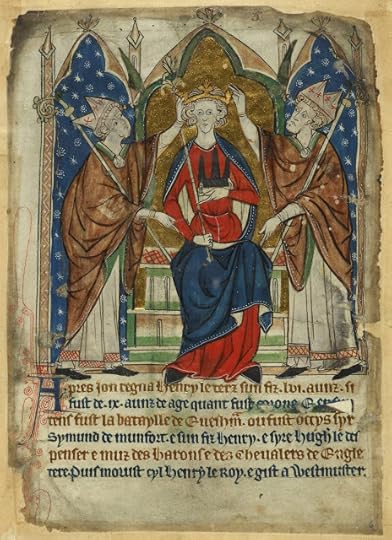

My review of The Two Eleanors of Henry III: the lives of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, by Darren Baker.

The Two Eleanors of Henry III by Darren Baker is a dual biography of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, respectively the wife and sister of Henry III of England (reigned 1216-72). It is an effort to focus on the lives of two high-ranking noblewomen of the era, as a welcome change from the usual male-dominated narratives. The book also casts a radically different light on the nature and motives of some of the famous protagonists of the era, notably Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester and chief driver of the reform movement in England.

Before reading this, I had noticed a few prickly reviews that complained of the difficulty of telling the two Eleanors apart in the narrative. Perceptions differ, of course, but I didn’t find it difficult to distinguish between them; any more than (for example) King Henry and his nephew Henry of Almaine. The Eleanors were alike in some respects: forceful, intelligent, a great influence on their husbands, but they led very different lives.

It is true that the Eleanors are sometimes overshadowed by their husbands in the text, but that is inevitable given the nature of the subject. Men typically wielded power - officially, at any rate - and it is easier to trace their actions. Even so, Baker quotes some remarkable letters and accounts for the women. These include a series of correspondence between Eleanor de Montfort and a stuffy cleric, Adam Marsh, who spent much of his time advising her to show humility, as a woman ‘should’, and not to argue with her spouse. Eleanor paid no attention and revelled in jewellery and expensive clothing. Neither Eleanor was afraid to clash with their husbands, and one particularly bitter row between Eleanor of Provence and Henry leaps off the page.

To his credit, Baker makes no effort to conceal the darker side of the Eleanors. Like her husband, Eleanor de Montfort was an oppressive landlord who evicted tenants and screwed down hard on the poor. Eleanor of Provence took blood money from the Jews and profited from the sale of Jewish bonds to Christians, one of the most notorious rackets of the age. She also had a tendency to appoint corrupt officials, such as Geoffrey Langley and Brother William of Tarentum, said to have ‘gaped after money like a horseleech after blood’. The appointment of Langley in North Wales proved a disaster, as his money-grubbing and efforts to shire the Four Cantreds triggered a full-scale Welsh revolt.

Money is a dominant theme. Everyone is out to get it, especially the Montforts. I have never been a great fan of Simon and his hair shirt, but hadn’t realised quite how grasping and deceitful the man was. He and his wife attempted to sabotage the Treaty of Paris, one of the great peace agreements of the age, simply to pressure Henry to satisfy outstanding claims for cash. Simon also comes across as a crude bully who routinely threatened opponents in council with physical violence. He betrayed and undermined Henry on several occasions, planted an agent in Rome to secretly work against the king, and generally pursued his own self-interest at all times. So much for Saint Simon.

Baker also deprives Simon of his greatest glory i.e. his alleged status as the founder of parliamentary democracy in England. This honour actually belongs to Eleanor of Provence. In 1254, while Henry was abroad, the queen presided over the first democratic mandate in England. This was over a decade before Simon’s famous assemblies, an inconvenient fact that appears to have been brushed under the carpet.

If I have a criticism, it is that the first third of the book is a little slow. This is partially due to the youth of the protagonists: Eleanor of Provence was only 12 when she married Henry, and naturally had little influence until she matured. Simon, meanwhile, is little more than a hopeful foreign adventurer angling for a rich bride. Henry’s reign itself is a bit of a grind for the first decade, as the young king struggles to assert himself and has to cope with the machinations of his nobles, including the remarkably unpleasant Richard Marshall. The pace picks up from about 1235 onwards, when the personalities of the two duelling couples really come into their own. The most interesting figure at this early stage is Blanche of Castile, the formidable queen of France, who effortlessly unpicked Henry’s attempts to forge dynastic alliances in France. A biography of Blanche would be most welcome.

The climax is reached in the great power-struggle of the reform period, when Henry and Simon (and their wives) ended up at daggers drawn. This was a tragedy on a personal as well as national level, as two couples who had known each other for decades ended up as bitter enemies. Their problems are exacerbated by the rise of Henry’s heir, a wayward tyro named Edward Longshanks. For a king who would have no favourites, Edward was surprisingly malleable at this stage, dragged about by various factions in his pursuit of independence. His infatuation with Simon caused his parents endless heartache, until the scales fell from his eyes when Queen Eleanor was almost killed by a mob in London, stirred up by Montfortian sympathizers. The slaughter of Evesham - more of a mass execution than a battle - lumbered Edward with a blood-feud, though he did his best to reconcile Simon’s widow and her children.

Overall this is an epic tale, recounting four extraordinary intertwined lives, and how their successes and failures wrought permanent changes in England. It ends on a slightly melancholy note, with both Eleanors relegated to the background in their declining years. Perhaps the author could have made a little more of Eleanor de Montfort’s last significant decision, the marriage alliance with Prince Llywelyn of Wales, although the consequences of that might easily fill a separate book. The Two Eleanors does a fine job of shining an overdue light on two fascinating and powerful - in the true sense of the word - medieval noblewomen.

The Two Eleanors on Amazon US

The Two Eleanors on Amazon UK

The Two Eleanors of Henry III by Darren Baker is a dual biography of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort, respectively the wife and sister of Henry III of England (reigned 1216-72). It is an effort to focus on the lives of two high-ranking noblewomen of the era, as a welcome change from the usual male-dominated narratives. The book also casts a radically different light on the nature and motives of some of the famous protagonists of the era, notably Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester and chief driver of the reform movement in England.

Before reading this, I had noticed a few prickly reviews that complained of the difficulty of telling the two Eleanors apart in the narrative. Perceptions differ, of course, but I didn’t find it difficult to distinguish between them; any more than (for example) King Henry and his nephew Henry of Almaine. The Eleanors were alike in some respects: forceful, intelligent, a great influence on their husbands, but they led very different lives.

It is true that the Eleanors are sometimes overshadowed by their husbands in the text, but that is inevitable given the nature of the subject. Men typically wielded power - officially, at any rate - and it is easier to trace their actions. Even so, Baker quotes some remarkable letters and accounts for the women. These include a series of correspondence between Eleanor de Montfort and a stuffy cleric, Adam Marsh, who spent much of his time advising her to show humility, as a woman ‘should’, and not to argue with her spouse. Eleanor paid no attention and revelled in jewellery and expensive clothing. Neither Eleanor was afraid to clash with their husbands, and one particularly bitter row between Eleanor of Provence and Henry leaps off the page.

To his credit, Baker makes no effort to conceal the darker side of the Eleanors. Like her husband, Eleanor de Montfort was an oppressive landlord who evicted tenants and screwed down hard on the poor. Eleanor of Provence took blood money from the Jews and profited from the sale of Jewish bonds to Christians, one of the most notorious rackets of the age. She also had a tendency to appoint corrupt officials, such as Geoffrey Langley and Brother William of Tarentum, said to have ‘gaped after money like a horseleech after blood’. The appointment of Langley in North Wales proved a disaster, as his money-grubbing and efforts to shire the Four Cantreds triggered a full-scale Welsh revolt.

Money is a dominant theme. Everyone is out to get it, especially the Montforts. I have never been a great fan of Simon and his hair shirt, but hadn’t realised quite how grasping and deceitful the man was. He and his wife attempted to sabotage the Treaty of Paris, one of the great peace agreements of the age, simply to pressure Henry to satisfy outstanding claims for cash. Simon also comes across as a crude bully who routinely threatened opponents in council with physical violence. He betrayed and undermined Henry on several occasions, planted an agent in Rome to secretly work against the king, and generally pursued his own self-interest at all times. So much for Saint Simon.

Baker also deprives Simon of his greatest glory i.e. his alleged status as the founder of parliamentary democracy in England. This honour actually belongs to Eleanor of Provence. In 1254, while Henry was abroad, the queen presided over the first democratic mandate in England. This was over a decade before Simon’s famous assemblies, an inconvenient fact that appears to have been brushed under the carpet.

If I have a criticism, it is that the first third of the book is a little slow. This is partially due to the youth of the protagonists: Eleanor of Provence was only 12 when she married Henry, and naturally had little influence until she matured. Simon, meanwhile, is little more than a hopeful foreign adventurer angling for a rich bride. Henry’s reign itself is a bit of a grind for the first decade, as the young king struggles to assert himself and has to cope with the machinations of his nobles, including the remarkably unpleasant Richard Marshall. The pace picks up from about 1235 onwards, when the personalities of the two duelling couples really come into their own. The most interesting figure at this early stage is Blanche of Castile, the formidable queen of France, who effortlessly unpicked Henry’s attempts to forge dynastic alliances in France. A biography of Blanche would be most welcome.

The climax is reached in the great power-struggle of the reform period, when Henry and Simon (and their wives) ended up at daggers drawn. This was a tragedy on a personal as well as national level, as two couples who had known each other for decades ended up as bitter enemies. Their problems are exacerbated by the rise of Henry’s heir, a wayward tyro named Edward Longshanks. For a king who would have no favourites, Edward was surprisingly malleable at this stage, dragged about by various factions in his pursuit of independence. His infatuation with Simon caused his parents endless heartache, until the scales fell from his eyes when Queen Eleanor was almost killed by a mob in London, stirred up by Montfortian sympathizers. The slaughter of Evesham - more of a mass execution than a battle - lumbered Edward with a blood-feud, though he did his best to reconcile Simon’s widow and her children.

Overall this is an epic tale, recounting four extraordinary intertwined lives, and how their successes and failures wrought permanent changes in England. It ends on a slightly melancholy note, with both Eleanors relegated to the background in their declining years. Perhaps the author could have made a little more of Eleanor de Montfort’s last significant decision, the marriage alliance with Prince Llywelyn of Wales, although the consequences of that might easily fill a separate book. The Two Eleanors does a fine job of shining an overdue light on two fascinating and powerful - in the true sense of the word - medieval noblewomen.

The Two Eleanors on Amazon US

The Two Eleanors on Amazon UK

Published on January 23, 2020 11:50

Was Ferrers the man in the Hood (1)?

Yesterday I posted an account of a Robin Hood ballad from the chronicle of Walter Bower, which placed the legendary outlaw in the year 1266, during the Montfortian wars in England.

Another interesting reference is The Pedigree of Robert Earle Fferrers and Derby. This obscure document dates from the mid-17th century and is a history of the medieval earls of Derby and their descendents. It is anonymous, but the text shows signs of being derived from an earlier source. The entry for Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby (1239-79) reads as follows:

“Upon a certaine day, but being not able to pay and perform the same, his said justiar assigned over their mortgage unto the said lord Edmund who ENTERED & enjoyed the said lands, whereupon this Earle Robert being discontented with some servants retired himself into the fforest of Sherwood and other places in the county of nottingham & darby living by robbery and depredations until he was outlawed, then being prosecuted he fledd northwards and for feare of being apprehended & taken, gott to the nunnerie of Kirklees in Yorkshire (now the inheritance of Sir John Armitage Baronet) where he concealed himself untill he opened a vaine (cancelled) some vaines and voluntarily bledd to death, and was buried in the open field neare the said nunnerie about seven miles from Wakefield, over whole grave is a stone with some obsolute letters not to be read and now to be soone called Robin Hoods grave & formerly an arbour of trees and wood.”

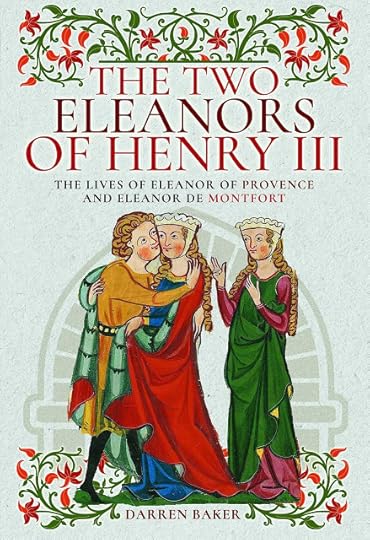

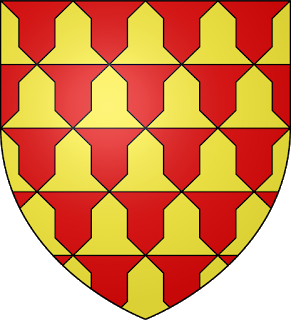

The arms of Robert de Ferrers

The arms of Robert de Ferrers

This refers to the earl’s disinheritance in 1269 in favour of Edmund of Lancaster, second son of Henry III. Ferrers is known to have led a band of outlaws in the High Peak in Derbyshire and other places, but the really interesting bit is the account of his death. In the early ballads, Robin Hood is treacherously bled to death at Kirklees priory. In the above snippet, Ferrers dies at Kirklees after bleeding himself to death. This appears to be a reference to his gout: a hereditary condition that was treated by bleeding the patient.

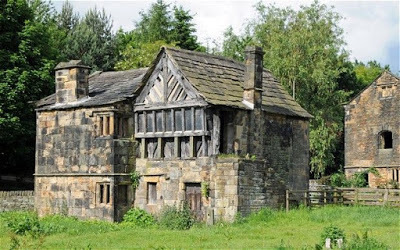

Kirklees PrioryThus, the life and death of Robert de Ferrers was merged with the legend of Robin Hood. Granted, the tradition is fairly late, but there are other clues.

Kirklees PrioryThus, the life and death of Robert de Ferrers was merged with the legend of Robin Hood. Granted, the tradition is fairly late, but there are other clues.

Another interesting reference is The Pedigree of Robert Earle Fferrers and Derby. This obscure document dates from the mid-17th century and is a history of the medieval earls of Derby and their descendents. It is anonymous, but the text shows signs of being derived from an earlier source. The entry for Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby (1239-79) reads as follows:

“Upon a certaine day, but being not able to pay and perform the same, his said justiar assigned over their mortgage unto the said lord Edmund who ENTERED & enjoyed the said lands, whereupon this Earle Robert being discontented with some servants retired himself into the fforest of Sherwood and other places in the county of nottingham & darby living by robbery and depredations until he was outlawed, then being prosecuted he fledd northwards and for feare of being apprehended & taken, gott to the nunnerie of Kirklees in Yorkshire (now the inheritance of Sir John Armitage Baronet) where he concealed himself untill he opened a vaine (cancelled) some vaines and voluntarily bledd to death, and was buried in the open field neare the said nunnerie about seven miles from Wakefield, over whole grave is a stone with some obsolute letters not to be read and now to be soone called Robin Hoods grave & formerly an arbour of trees and wood.”

The arms of Robert de Ferrers

The arms of Robert de FerrersThis refers to the earl’s disinheritance in 1269 in favour of Edmund of Lancaster, second son of Henry III. Ferrers is known to have led a band of outlaws in the High Peak in Derbyshire and other places, but the really interesting bit is the account of his death. In the early ballads, Robin Hood is treacherously bled to death at Kirklees priory. In the above snippet, Ferrers dies at Kirklees after bleeding himself to death. This appears to be a reference to his gout: a hereditary condition that was treated by bleeding the patient.

Kirklees PrioryThus, the life and death of Robert de Ferrers was merged with the legend of Robin Hood. Granted, the tradition is fairly late, but there are other clues.

Kirklees PrioryThus, the life and death of Robert de Ferrers was merged with the legend of Robin Hood. Granted, the tradition is fairly late, but there are other clues.

Published on January 23, 2020 04:42