David Pilling's Blog, page 34

January 22, 2020

Normal relations

Gaston and Llywelyn.

At Rhuddlan on 15 November 1277, five days after he had ratified the terms of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s submission, Edward I wrote to King Philip of France. His subject was the long-running saga of Gaston de Béarn, still with no end in sight.

Rhuddlan castle

Rhuddlan castle

Edward had sent Gaston back to France, in the expectation that he would be punished by Philip. The French king’s notion of punishment was to give Gaston seisin of his lands and castles and restore him to the allegiance of the king of England. As Edward had made clear in his letter, this was not the sentence he had been seeking from his cousin. It was all the more bizzare, since Philip had previously sent the Gascon rebel to England with a noose round his neck.

The letters composed at Rhuddlan laid great stress on Edward’s will (voluntas, volunte). They make for an interesting comparison to the terms of Llywelyn’s surrender: the Welsh prince had given himself up entirely to the will of the king - “supponet se voluntati et misericordie dicti domini regis.” This was written in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn’s total submission to the mercy of a king who was able to deal with an intransigent vassal directly, with overwhelming military force, and with no reference to any other secular power.

Gaston was also Edward’s vassal, but unlike Llywelyn he had two overlords. The English king could not pass sentence on him without reference to his French counterpart, and Philip was playing the situation to his advantage. From Paris, Edward’s seneschal reported that Philip was inquiring into matters in Gascony which were no concern of the French court; in short, he was using Gaston as an opportunity to extend French influence into the duchy.

The arms of Gwynedd

The arms of Gwynedd

With all this in mind, Edward changed his policy. He could not kill or disinherit Gaston, nor could he afford to let Philip exploit him. So, in March 1278, he received Gaston into his grace, restored his lands and castles and awarded him an annual fee of 2000 livres tournois from the customs of Bordeaux. This was the same fee Gaston had been awarded before the planned marriage of his daughter, Constance, to Henry of Almaine. That plan fell through when Henry was murdered in Italy by the Montfort brothers, but now Edward revived the stipend in an effort to resume normal relations.

The conciliation paid off: Gaston was well placed to serve Edward in Gascony and further afield, and became the king’s loyal servant. His many services as an envoy and military captain were awarded with the grant of Lados, an estate on the Gironde. He would eventually die in his bed of natural causes. Llywelyn was not half so fortunate.

At Rhuddlan on 15 November 1277, five days after he had ratified the terms of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd’s submission, Edward I wrote to King Philip of France. His subject was the long-running saga of Gaston de Béarn, still with no end in sight.

Rhuddlan castle

Rhuddlan castleEdward had sent Gaston back to France, in the expectation that he would be punished by Philip. The French king’s notion of punishment was to give Gaston seisin of his lands and castles and restore him to the allegiance of the king of England. As Edward had made clear in his letter, this was not the sentence he had been seeking from his cousin. It was all the more bizzare, since Philip had previously sent the Gascon rebel to England with a noose round his neck.

The letters composed at Rhuddlan laid great stress on Edward’s will (voluntas, volunte). They make for an interesting comparison to the terms of Llywelyn’s surrender: the Welsh prince had given himself up entirely to the will of the king - “supponet se voluntati et misericordie dicti domini regis.” This was written in the immediate aftermath of Llywelyn’s total submission to the mercy of a king who was able to deal with an intransigent vassal directly, with overwhelming military force, and with no reference to any other secular power.

Gaston was also Edward’s vassal, but unlike Llywelyn he had two overlords. The English king could not pass sentence on him without reference to his French counterpart, and Philip was playing the situation to his advantage. From Paris, Edward’s seneschal reported that Philip was inquiring into matters in Gascony which were no concern of the French court; in short, he was using Gaston as an opportunity to extend French influence into the duchy.

The arms of Gwynedd

The arms of GwyneddWith all this in mind, Edward changed his policy. He could not kill or disinherit Gaston, nor could he afford to let Philip exploit him. So, in March 1278, he received Gaston into his grace, restored his lands and castles and awarded him an annual fee of 2000 livres tournois from the customs of Bordeaux. This was the same fee Gaston had been awarded before the planned marriage of his daughter, Constance, to Henry of Almaine. That plan fell through when Henry was murdered in Italy by the Montfort brothers, but now Edward revived the stipend in an effort to resume normal relations.

The conciliation paid off: Gaston was well placed to serve Edward in Gascony and further afield, and became the king’s loyal servant. His many services as an envoy and military captain were awarded with the grant of Lados, an estate on the Gironde. He would eventually die in his bed of natural causes. Llywelyn was not half so fortunate.

Published on January 22, 2020 08:34

Dispose of this man

Limoges and Béarn (8)

At the September 1274 parliament in Paris, Gaston de Béarn accused his overlord Edward I of being a traitor and a liar, and challenged him to single combat. He also prayed that the “King of England be chastised and made to suffer by the law of the land.”

Seal of Margaret of Provence

Seal of Margaret of Provence

Feudal suzerains were not in the habit of brawling with their vassals. To answer the challenge, Edward sent five knights to the French court charged to introduce themselves as his champions. A Gascon knight, Gilles de Noaillan, was so outraged he wrote a letter to the king, - “moun seigneur, le Roy de d’Engleterre” - requesting the honour of beating the crap out of the insolent viscomte. Gaston responded by declaring he would fight no-one except Edward himself.

The French king, presiding as judge, declared there would be no combat. Instead the adversaries were summoned to the next session of parlement at Candlemas.

King Philip was in a cleft stick. On the one hand, he rather enjoyed witnessing the embarassment of his cousin. On the other, Gaston was a pain in everyone’s backside and had done undeniable wrongs to his overlord. In the end Philip decided to throw the problem back at Edward, and in 1275 packed Gaston off to England for judgement.

There were suspicions over Philippe’s intentions. One of Edward’s lawyers in Paris, Pierre Odon, sent a stark warning to his master:

“You know how much Gaston offended you; take guard that he dare not do more from now on; otherwise the barons of Gascony would misuse it.”

Edward received all kinds of mixed messages. His aunt, Margaret of Provence, sent him a letter requesting Gaston be shown mercy. It seems Philip took the opposite view. When the captive finally turned up at Westminster, escorted by French soldiers, he had a noose round his neck. Dispose of this man, cousin Ned, was the not-very-subtle message.

Gaston was now at Edward’s mercy. He was brought before parliament and there renounced all his insults against the king. This was declared sufficient, and all proceedings at law were formally ended. Only one point remained: what punishment should be inflicted?

Edward promptly threw Gaston back at Philip.

At the September 1274 parliament in Paris, Gaston de Béarn accused his overlord Edward I of being a traitor and a liar, and challenged him to single combat. He also prayed that the “King of England be chastised and made to suffer by the law of the land.”

Seal of Margaret of Provence

Seal of Margaret of ProvenceFeudal suzerains were not in the habit of brawling with their vassals. To answer the challenge, Edward sent five knights to the French court charged to introduce themselves as his champions. A Gascon knight, Gilles de Noaillan, was so outraged he wrote a letter to the king, - “moun seigneur, le Roy de d’Engleterre” - requesting the honour of beating the crap out of the insolent viscomte. Gaston responded by declaring he would fight no-one except Edward himself.

The French king, presiding as judge, declared there would be no combat. Instead the adversaries were summoned to the next session of parlement at Candlemas.

King Philip was in a cleft stick. On the one hand, he rather enjoyed witnessing the embarassment of his cousin. On the other, Gaston was a pain in everyone’s backside and had done undeniable wrongs to his overlord. In the end Philip decided to throw the problem back at Edward, and in 1275 packed Gaston off to England for judgement.

There were suspicions over Philippe’s intentions. One of Edward’s lawyers in Paris, Pierre Odon, sent a stark warning to his master:

“You know how much Gaston offended you; take guard that he dare not do more from now on; otherwise the barons of Gascony would misuse it.”

Edward received all kinds of mixed messages. His aunt, Margaret of Provence, sent him a letter requesting Gaston be shown mercy. It seems Philip took the opposite view. When the captive finally turned up at Westminster, escorted by French soldiers, he had a noose round his neck. Dispose of this man, cousin Ned, was the not-very-subtle message.

Gaston was now at Edward’s mercy. He was brought before parliament and there renounced all his insults against the king. This was declared sufficient, and all proceedings at law were formally ended. Only one point remained: what punishment should be inflicted?

Edward promptly threw Gaston back at Philip.

Published on January 22, 2020 01:13

January 21, 2020

Of cats and dogs

Limoges and Béarn (7)

In July 1274 William de Valence, Edward I’s Lusigan half-uncle, laid siege to Aixe castle in the Limousin with an army of Englishmen and French militia. The castle was defended by the soldiers of the Viscomtesse Marguerite of Limoges, also cooped up inside.

The ruins of Aixe castle

The ruins of Aixe castle

Valence brought an engineer, named Civry, who devised an interesting siege engine. This thing lobbed balls of burning sulphur, a weapon apparently not used again by the English until the siege of Brechin in Scotland in 1303. For nine days Civry’s invention pounded the walls, while the defenders hurled bits of timber and broken furniture down on the besiegers. Valence apparently kept his own men in reserve and let the militia do all the rough stuff: it was their fight, after all.

The siege ended abruptly on 24 July, when a herald from Paris ordered both parties to cease hostilities. Philippe le Hardi, king of France, had been slow to deal with the private war in Limoges, but now he took control of the affair. He ordered the king of England not to receive any more oaths of fealty from Limoges, not to block the justice of the Viscomtesse, not to protect the bourgeois and not to maintain a bailiff in the city.

To add insult to injury, the Candlemas parliament of 1275 ordered Edward to pay war damages amounting to 22, 613 livres tournois. It is difficult to figure out how much this was worth in English currency, but in the fifteenth century one English pound sterling was worth 8.5 times as much as the livres tournois. This gives a ballpark figure of £2600 Edward was required to pay - hefty enough, given that the average income of an English baron in this era was about £300 per annum.

On top of that was the political embarrassment. Edward had tried to act on principle in Limoges, and ended up being slapped with a bill for war damages. Philippe had not exactly been helpful, and the chronicler of Limoges remarked on the peculiar relationship of the two kings; there was, he said, a ‘cat-and-dog love between them’:

“Hic amor dici potest amor cati et canis.”

To add to Edward’s woes, Gaston de Béarn was still carping away in the background. Never one to accept defeat, Gaston had appealed to the French parlement against Edward, and appeared in person before Philip. Here he denounced the English king as a traitor, a liar and an unfair judge, and challenged him to single combat. In a final flourish, he literally threw down his gauntlet.

Gaston had really gone too far this time. There were certain rules to this game, and challenging one’s feudal overlord to a duel was not one of them.

In July 1274 William de Valence, Edward I’s Lusigan half-uncle, laid siege to Aixe castle in the Limousin with an army of Englishmen and French militia. The castle was defended by the soldiers of the Viscomtesse Marguerite of Limoges, also cooped up inside.

The ruins of Aixe castle

The ruins of Aixe castleValence brought an engineer, named Civry, who devised an interesting siege engine. This thing lobbed balls of burning sulphur, a weapon apparently not used again by the English until the siege of Brechin in Scotland in 1303. For nine days Civry’s invention pounded the walls, while the defenders hurled bits of timber and broken furniture down on the besiegers. Valence apparently kept his own men in reserve and let the militia do all the rough stuff: it was their fight, after all.

The siege ended abruptly on 24 July, when a herald from Paris ordered both parties to cease hostilities. Philippe le Hardi, king of France, had been slow to deal with the private war in Limoges, but now he took control of the affair. He ordered the king of England not to receive any more oaths of fealty from Limoges, not to block the justice of the Viscomtesse, not to protect the bourgeois and not to maintain a bailiff in the city.

To add insult to injury, the Candlemas parliament of 1275 ordered Edward to pay war damages amounting to 22, 613 livres tournois. It is difficult to figure out how much this was worth in English currency, but in the fifteenth century one English pound sterling was worth 8.5 times as much as the livres tournois. This gives a ballpark figure of £2600 Edward was required to pay - hefty enough, given that the average income of an English baron in this era was about £300 per annum.

On top of that was the political embarrassment. Edward had tried to act on principle in Limoges, and ended up being slapped with a bill for war damages. Philippe had not exactly been helpful, and the chronicler of Limoges remarked on the peculiar relationship of the two kings; there was, he said, a ‘cat-and-dog love between them’:

“Hic amor dici potest amor cati et canis.”

To add to Edward’s woes, Gaston de Béarn was still carping away in the background. Never one to accept defeat, Gaston had appealed to the French parlement against Edward, and appeared in person before Philip. Here he denounced the English king as a traitor, a liar and an unfair judge, and challenged him to single combat. In a final flourish, he literally threw down his gauntlet.

Gaston had really gone too far this time. There were certain rules to this game, and challenging one’s feudal overlord to a duel was not one of them.

Published on January 21, 2020 05:37

January 20, 2020

The keys to the city

Limoges and Béarn (6)

After the surrender of Gaston de Béarn, Edward I turned about and went north, to deal with the situation at Limoges. On 10 May 1274 he entered the town and was received in ‘processionnellement’ (truimphal parade) by the bourgeois. Shortly after his arrival, abbots of the principal monasteries begged him to restore peace with the Viscomtesse.

Edward was wary of provoking an open breach with the French court, so he dispatched messengers to Paris. While he awaited their return, the soldiers of the Viscomtesse started to attack the bourgeois again. The Limousin was reduced to a pitiful state by this private war:

“All prices on commodities had increased; mortality was extreme; people had never seen so many robbers along the roads nor had they ever seen so many corbels (fortifications) defending the towers of churches.”

- Histoire de France, XXI

The tomb of William de Valence

The tomb of William de Valence

The bourgeois continued to beg Edward to defend them. He would do nothing until word arrived from Paris, so went off hunting in the mountains instead. When he came back, on 5 June, he found his messengers had returned empty handed. Philip refused to grant a truce, or even a letter.

The ball was left in Edward’s court. On 7 June the bourgeois made one last desperate plea and threw the keys of the city down before him. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Edward gave way to tears and released the people of Limoges from the oath they had given him. He could not, he said, disobey the King of France, but neither would he abandon those who wished to retain their fealty to the English crown.

His solution was to depart from Limoges, but leave most of his soldiers behind to defend the city. On 7 July his uncle William de Valence arrrived with two hundred English men-at-arms and an engineer, who started to construct war-machines. A few days later Valence led an army of Englishmen and bourgeois militia to attack the Viscomtesse.

After the surrender of Gaston de Béarn, Edward I turned about and went north, to deal with the situation at Limoges. On 10 May 1274 he entered the town and was received in ‘processionnellement’ (truimphal parade) by the bourgeois. Shortly after his arrival, abbots of the principal monasteries begged him to restore peace with the Viscomtesse.

Edward was wary of provoking an open breach with the French court, so he dispatched messengers to Paris. While he awaited their return, the soldiers of the Viscomtesse started to attack the bourgeois again. The Limousin was reduced to a pitiful state by this private war:

“All prices on commodities had increased; mortality was extreme; people had never seen so many robbers along the roads nor had they ever seen so many corbels (fortifications) defending the towers of churches.”

- Histoire de France, XXI

The tomb of William de Valence

The tomb of William de ValenceThe bourgeois continued to beg Edward to defend them. He would do nothing until word arrived from Paris, so went off hunting in the mountains instead. When he came back, on 5 June, he found his messengers had returned empty handed. Philip refused to grant a truce, or even a letter.

The ball was left in Edward’s court. On 7 June the bourgeois made one last desperate plea and threw the keys of the city down before him. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Edward gave way to tears and released the people of Limoges from the oath they had given him. He could not, he said, disobey the King of France, but neither would he abandon those who wished to retain their fealty to the English crown.

His solution was to depart from Limoges, but leave most of his soldiers behind to defend the city. On 7 July his uncle William de Valence arrrived with two hundred English men-at-arms and an engineer, who started to construct war-machines. A few days later Valence led an army of Englishmen and bourgeois militia to attack the Viscomtesse.

Published on January 20, 2020 07:51

Complete submission

Limoges and Béarn (5)

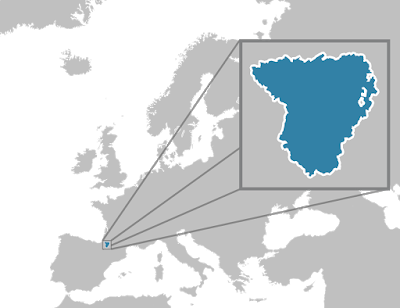

After the collapse of his rebellion in Gascony, Gaston de Béarn fled south to take refuge in his castles on the edge of the Pyrenees. Edward I was in no hurry to follow. The war in Limoge was suspended, for the moment, so he could take his time in bringing the troublesome viscomte to heel.

On 14 December 1273 Edward was at Mimizan on the coast of Gascony, now part of the Landes department of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Here he granted the commune a charter, whereby in exchange for 200 livres angevin to help fund his war against Gaston, the king guaranteed that the menfolk of Mimizan would never have to do military service in the future. Such a concession might suggest the commune was tiny and of no military value, or that Edward took one look at the local youth and was only too glad to take the cash instead.

According to Rishanger, Edward then marched south to blockade Gaston in his strongest castle:

“Edward marched in great power with his army into Gaston's lands, forced him to flee, and besieged him in the strong and well-defended castle to which he had retreated.”

- William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

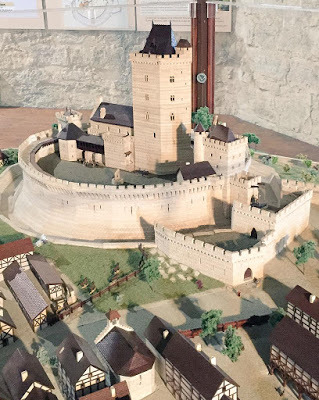

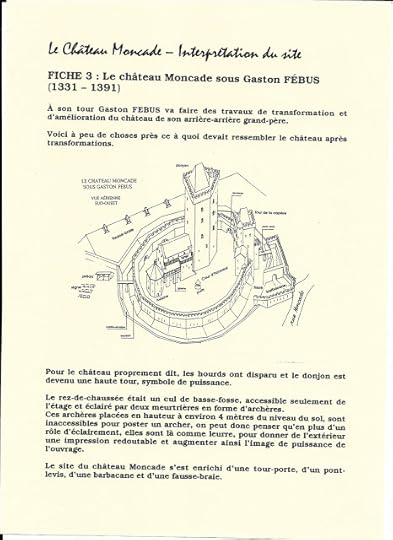

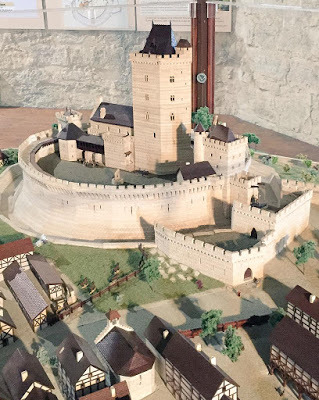

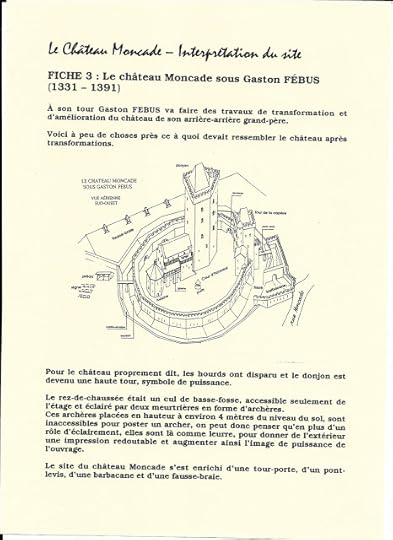

The castle in question was probably the Château Moncade, a castle and fortified bourg that Gaston had only started to build in 1242; ironically, with money granted by Henry III. Only part of the keep remains today, but it was quite impressive at the time (see pics).

Gaston’s brief revolt had collapsed into the dust. On 14 January 1274 he agreed to surrender via the mediation of a papal envoy, though the envoy could do no more than facilitate Gaston’s complete submission to the king’s will.

Thanks to Rich Price, as ever, for the various translations.

After the collapse of his rebellion in Gascony, Gaston de Béarn fled south to take refuge in his castles on the edge of the Pyrenees. Edward I was in no hurry to follow. The war in Limoge was suspended, for the moment, so he could take his time in bringing the troublesome viscomte to heel.

On 14 December 1273 Edward was at Mimizan on the coast of Gascony, now part of the Landes department of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Here he granted the commune a charter, whereby in exchange for 200 livres angevin to help fund his war against Gaston, the king guaranteed that the menfolk of Mimizan would never have to do military service in the future. Such a concession might suggest the commune was tiny and of no military value, or that Edward took one look at the local youth and was only too glad to take the cash instead.

According to Rishanger, Edward then marched south to blockade Gaston in his strongest castle:

“Edward marched in great power with his army into Gaston's lands, forced him to flee, and besieged him in the strong and well-defended castle to which he had retreated.”

- William of Rishanger, Chronica et Annales

The castle in question was probably the Château Moncade, a castle and fortified bourg that Gaston had only started to build in 1242; ironically, with money granted by Henry III. Only part of the keep remains today, but it was quite impressive at the time (see pics).

Gaston’s brief revolt had collapsed into the dust. On 14 January 1274 he agreed to surrender via the mediation of a papal envoy, though the envoy could do no more than facilitate Gaston’s complete submission to the king’s will.

Thanks to Rich Price, as ever, for the various translations.

Published on January 20, 2020 04:17

January 18, 2020

Philip's nose

Limoges and Béarn (4) In late October 1273 the king of France, Philippe le Hardi - who apparently had a very long nose - ordered everyone in Limoges to stop fighting and appear before him for judgement at Saint-Martin.

The text of Philip’s sentence was only discovered in the late 19th century. He ordered the king of England to surrender the oath of fidelity he had received from the bourgeois; if he neglected to do this, the seneschal of Périgord would force him. Philip also instructed Edward to abstain from fighting the Viscomtesse of Limoges, who would remain in possession of the town. A second letter was sent to Edward, this time a personal message, in which the French king told his cousin to remove his bailiff from Limoges and to recognise the right of Marguerite to armed justice in the event of rebellion.

In short, Edward was told to get the hell out. The English king was a long way to the south, embroiled in his dispute with Gaston de Béarn. For the moment he ignored Philip and got on with the business in hand. He persuaded the court of Gascony to provide testimony that Gaston had been summoned to appear before the king on three successive occasions. The culprit refused all three, so Edward was empowered to move against him.

On 11 November the assembly gave Edward the go-ahead for military action. This was very similar to the conflict with Prince Llywelyn of Wales a couple of years later, when the king gained parliamentary approval for war after Llywellyn had refused five separate summons.

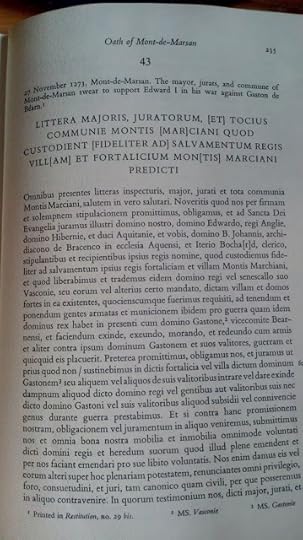

Mont-de-Marsan

Mont-de-Marsan

Edward marched into Marson and Gabardan, where all resistance collapsed after barely a fortnight. On 27 November Gaston’s daughter Constance came before the king and offered to yield up her father’s castles. She also forced the mayor and commune of Mont-de-Marsan to submit to Edward; the grovelling terms they offered are recorded in Gaston Register A.

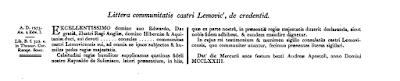

See translation of the text below:

“To all those who may look upon these present letters, the mayor, the jurats and the whole government of Mont-de-Marsan give greeting in true sincerity. You should know that we, in firm and solemn covenant, do promise and bind ourselves, and so swear on the Sacred Gospel of God, to our illustrious lord, the lord Edward, king of England, lord of Ireland and duke of Aquitaine, and to you, the lord of Saint John, archdeacon of Bracence in the church of Aque, and Iterius Bochard, clerk, who require and receive this commitment in the name of the king, that we shall faithfully defend for the security of the king the burgus and town of Mont-de-Marsan; and that we will deliver and hand over to the said lord king, or to his seneschal of Gascony, whether by their proven command or that of another, the said town and the fortified houses therein whensoever it may be required of us, so that the town may be garrisoned and defended by men at arms, for the purpose of the war which the lord king is presently conducting against the lord Gaston, viscount of Bearn; also for their carrying out therefrom warfare or whatsoever they please, whether in their going from there, their remaining there, or their returning there, in arms or otherwise, against the same lord Gaston and his supporters.

Furthermore, we promise, bind ourselves and swear as before that we will neither permit the entry of the said lord Gaston or any of his supporters into the said burgus and town nor permit them to cause therefrom any hurt to the said lord king, his men-at-arms or his supporters, nor shall we offer him any kind of aid or cooperation for the duration of this war. And if we shall in any way contravene this our promise, our covenant or our oath, we do submit ourselves and all our goods, whether movable or fixed, entirely to the will of the said lord king and his heirs, that they may be fully compensated by us according to their will and pleasure. Indeed, we give them or their proxies full power in this matter and do renounce all privilege, jurisdiction, customary rights and legal authority, whether canon or civil, by means of which we may in any way be able to contravene [this agreement]. In testimony of which, we, the said mayor, jurats and town government cause to be affixed here the seal of our community.

Enacted in the cloister of Mont-de-Marsan, in the presence and at the command of the lady Constance, of Martin, official of the court of Adour, of Fortanerius, prior of Mont-de-Marsan, of brother Raymond William de Morgohans, Guardian, and of Bertrand de la Dos and William Arnald de Mont Auser, squires. Given at Mont-de-Marsan, on the Monday before the feast of Saint Andrew the Apostle, in the year of our Lord 1273.'”

Many thanks to Rich Price for the above translation.

The text of Philip’s sentence was only discovered in the late 19th century. He ordered the king of England to surrender the oath of fidelity he had received from the bourgeois; if he neglected to do this, the seneschal of Périgord would force him. Philip also instructed Edward to abstain from fighting the Viscomtesse of Limoges, who would remain in possession of the town. A second letter was sent to Edward, this time a personal message, in which the French king told his cousin to remove his bailiff from Limoges and to recognise the right of Marguerite to armed justice in the event of rebellion.

In short, Edward was told to get the hell out. The English king was a long way to the south, embroiled in his dispute with Gaston de Béarn. For the moment he ignored Philip and got on with the business in hand. He persuaded the court of Gascony to provide testimony that Gaston had been summoned to appear before the king on three successive occasions. The culprit refused all three, so Edward was empowered to move against him.

On 11 November the assembly gave Edward the go-ahead for military action. This was very similar to the conflict with Prince Llywelyn of Wales a couple of years later, when the king gained parliamentary approval for war after Llywellyn had refused five separate summons.

Mont-de-Marsan

Mont-de-MarsanEdward marched into Marson and Gabardan, where all resistance collapsed after barely a fortnight. On 27 November Gaston’s daughter Constance came before the king and offered to yield up her father’s castles. She also forced the mayor and commune of Mont-de-Marsan to submit to Edward; the grovelling terms they offered are recorded in Gaston Register A.

See translation of the text below:

“To all those who may look upon these present letters, the mayor, the jurats and the whole government of Mont-de-Marsan give greeting in true sincerity. You should know that we, in firm and solemn covenant, do promise and bind ourselves, and so swear on the Sacred Gospel of God, to our illustrious lord, the lord Edward, king of England, lord of Ireland and duke of Aquitaine, and to you, the lord of Saint John, archdeacon of Bracence in the church of Aque, and Iterius Bochard, clerk, who require and receive this commitment in the name of the king, that we shall faithfully defend for the security of the king the burgus and town of Mont-de-Marsan; and that we will deliver and hand over to the said lord king, or to his seneschal of Gascony, whether by their proven command or that of another, the said town and the fortified houses therein whensoever it may be required of us, so that the town may be garrisoned and defended by men at arms, for the purpose of the war which the lord king is presently conducting against the lord Gaston, viscount of Bearn; also for their carrying out therefrom warfare or whatsoever they please, whether in their going from there, their remaining there, or their returning there, in arms or otherwise, against the same lord Gaston and his supporters.

Furthermore, we promise, bind ourselves and swear as before that we will neither permit the entry of the said lord Gaston or any of his supporters into the said burgus and town nor permit them to cause therefrom any hurt to the said lord king, his men-at-arms or his supporters, nor shall we offer him any kind of aid or cooperation for the duration of this war. And if we shall in any way contravene this our promise, our covenant or our oath, we do submit ourselves and all our goods, whether movable or fixed, entirely to the will of the said lord king and his heirs, that they may be fully compensated by us according to their will and pleasure. Indeed, we give them or their proxies full power in this matter and do renounce all privilege, jurisdiction, customary rights and legal authority, whether canon or civil, by means of which we may in any way be able to contravene [this agreement]. In testimony of which, we, the said mayor, jurats and town government cause to be affixed here the seal of our community.

Enacted in the cloister of Mont-de-Marsan, in the presence and at the command of the lady Constance, of Martin, official of the court of Adour, of Fortanerius, prior of Mont-de-Marsan, of brother Raymond William de Morgohans, Guardian, and of Bertrand de la Dos and William Arnald de Mont Auser, squires. Given at Mont-de-Marsan, on the Monday before the feast of Saint Andrew the Apostle, in the year of our Lord 1273.'”

Many thanks to Rich Price for the above translation.

Published on January 18, 2020 07:25

Ghastly Gaston

Limoges and Béarn (3)

“They will do nothing but rob the land, and burn and plunder, and put the people to ransom, and ride by night like thieves by twenty or thirty or forty in different parts.”

- Simon de Montfort to Henry III in 1250, reporting on the state of Gascony and the nature of the Gascony gentry. He was referring indirectly to Gaston Moncada, the perpetually dissatisfied Vicomte of Béarn.

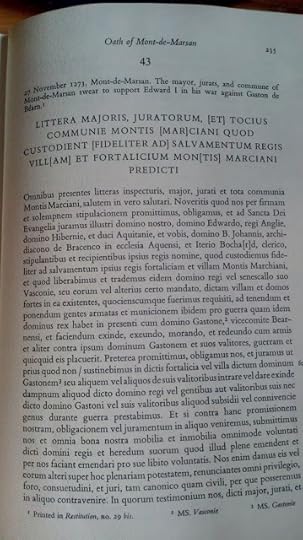

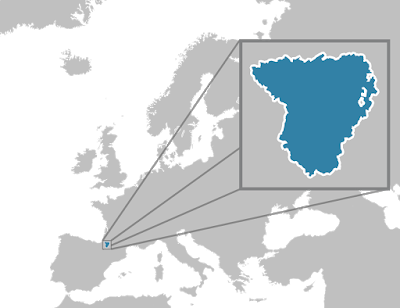

BéarnOver twenty years later, in 1273, Gaston went into revolt yet again. What he hoped to achieve is unclear. In his youth he had aspired to be seneschal of Gascony under Alfonso X, after the Castilian king had conquered the duchy from the English. That plan failed, and by the 1270s Castile was a staunch ally of England. Possibly he hoped to take advantage of the death of Henry III, or - this being Gaston - he was just being an asshole.

BéarnOver twenty years later, in 1273, Gaston went into revolt yet again. What he hoped to achieve is unclear. In his youth he had aspired to be seneschal of Gascony under Alfonso X, after the Castilian king had conquered the duchy from the English. That plan failed, and by the 1270s Castile was a staunch ally of England. Possibly he hoped to take advantage of the death of Henry III, or - this being Gaston - he was just being an asshole.

In the autumn of 1273, after he had sworn homage to Philippe le Hardi in Paris, Edward went south to deal with the problem. At first he sent one of his knights, Géraud de Laur, to Gaston’s castle at Orthez to try and negotiate. Gaston seized the man, threw him into prison and tortured him.

The English king's response demonstrated his wish to proceed in accordance with the customs of Gascony. His men arrested Gaston and imprisoned at Sault-de-Navailles, on the edge of the Pyrenees, where on 2 October the captive was induced to make several promises: he would do what was required of him by the court of St Sever, and otherwise yield himself up entirely to the king’s will.

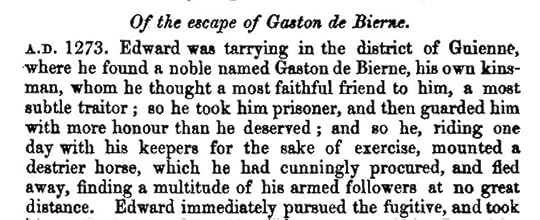

Gaston promptly broke his promise and escaped, in remarkably similar circumstances to Edward’s escape from Hereford, shortly before the battle of Evesham. He used exactly the same trick, galloping away on a fresh horse while his guards stood about like a bunch of lemons.

Still the king stayed his hand. In the British Isles he could deal with troublesome vassals as he liked, but in France he was merely the Duke of Aquitaine, and had to watch his step. At the same time he had to deal with the war raging beyond the northern borders of Gascony, in Limoges.

On 23 October Edward wrote to the seneschals of Gascony and Limousin, and the Viscount of Ventadour, asking them to rescue the town of Limoges from the predatory Viscomtesse Marguerite. Edward was doubly concerned, since his wife Eleanor was also shut up inside the town, having probably taken refuge in the abbey.

“They will do nothing but rob the land, and burn and plunder, and put the people to ransom, and ride by night like thieves by twenty or thirty or forty in different parts.”

- Simon de Montfort to Henry III in 1250, reporting on the state of Gascony and the nature of the Gascony gentry. He was referring indirectly to Gaston Moncada, the perpetually dissatisfied Vicomte of Béarn.

BéarnOver twenty years later, in 1273, Gaston went into revolt yet again. What he hoped to achieve is unclear. In his youth he had aspired to be seneschal of Gascony under Alfonso X, after the Castilian king had conquered the duchy from the English. That plan failed, and by the 1270s Castile was a staunch ally of England. Possibly he hoped to take advantage of the death of Henry III, or - this being Gaston - he was just being an asshole.

BéarnOver twenty years later, in 1273, Gaston went into revolt yet again. What he hoped to achieve is unclear. In his youth he had aspired to be seneschal of Gascony under Alfonso X, after the Castilian king had conquered the duchy from the English. That plan failed, and by the 1270s Castile was a staunch ally of England. Possibly he hoped to take advantage of the death of Henry III, or - this being Gaston - he was just being an asshole.In the autumn of 1273, after he had sworn homage to Philippe le Hardi in Paris, Edward went south to deal with the problem. At first he sent one of his knights, Géraud de Laur, to Gaston’s castle at Orthez to try and negotiate. Gaston seized the man, threw him into prison and tortured him.

The English king's response demonstrated his wish to proceed in accordance with the customs of Gascony. His men arrested Gaston and imprisoned at Sault-de-Navailles, on the edge of the Pyrenees, where on 2 October the captive was induced to make several promises: he would do what was required of him by the court of St Sever, and otherwise yield himself up entirely to the king’s will.

Gaston promptly broke his promise and escaped, in remarkably similar circumstances to Edward’s escape from Hereford, shortly before the battle of Evesham. He used exactly the same trick, galloping away on a fresh horse while his guards stood about like a bunch of lemons.

Still the king stayed his hand. In the British Isles he could deal with troublesome vassals as he liked, but in France he was merely the Duke of Aquitaine, and had to watch his step. At the same time he had to deal with the war raging beyond the northern borders of Gascony, in Limoges.

On 23 October Edward wrote to the seneschals of Gascony and Limousin, and the Viscount of Ventadour, asking them to rescue the town of Limoges from the predatory Viscomtesse Marguerite. Edward was doubly concerned, since his wife Eleanor was also shut up inside the town, having probably taken refuge in the abbey.

Published on January 18, 2020 06:59

January 17, 2020

The battle of Limoges

Limoges and Béarn (2)

On 8 August 1273 the armies of the Queen of England and the Viscomtesse of Limoges faced each other on an open plain between Aixes and the town of Limoges. It is tempting to say that both ladies were present and in command, but it seems not. Eleanor of Castile’s Gascons were led by Luke de Tany, seneschal of Gascony, while the French were led by Géraut de Themines, governor of Limoges.

The battle that followed, totally ignored by English chroniclers, was described by the Chronica Majora of Limoges:

“In the same year, on the day following the feast of Saint Sixtus, the king of England's seneschal, who had come to the aid of the citizens of Limoges against the viscountess of Limoges, had a great victory over her army, between Aixe and the town of Limoges. He wounded and captured many of them, killing a nobleman and many others, without loss to him or his allies, at which the townsfolk rejoiced greatly. Moreover, they captured the banner of Girbert de Tamines. On the feast of Saint Laurence following [two days later] one of the viscountess's men was found dead and many horses on both sides too, but the viscountess lost many more.”*

The arms of William de Valence (1225-1296)

The arms of William de Valence (1225-1296)

Edward I’s seneschal had won a battle for his master, and the bourgeois of Limoges celebrated their deliverance. On 27 August the king’s uncle, William de Valence, arrived with letters from Edward requesting the inhabitants of the town to swear an oath of fealty to him as Duke of Aquitaine. This went against previous judgements of the court of Paris, but the bourgeois agreed wholeheartedly. The service of the oath took place on 3 September, in the abbey of Saint-Martial, in the presence of the consuls and of all the community.

The fighting continued. On 16 September the bourgeois won another skirmish, and were so encouraged they decided to try a second attack upon Marguerite’s castle at Aixe. They marched on Sunday morning, with drums and trumpets, crossed the ford of Vienne and burnt the borough of Saint-Priest. They also roughed up the local priest and carried off the silver chalice, missal and candles from the church. At the gates of Aixe panic set in, and the mob fled in all directions, throwing away their weapons and hiding in the woods. A few days later Marguerite sent her men to burn the vineyards near Saint-Martial.

Edward could not move from Gascony. In September, even as war raged in the Limousin, Gaston de Béarn raised his head again.

*Thanks to Rich Price for the translation.

On 8 August 1273 the armies of the Queen of England and the Viscomtesse of Limoges faced each other on an open plain between Aixes and the town of Limoges. It is tempting to say that both ladies were present and in command, but it seems not. Eleanor of Castile’s Gascons were led by Luke de Tany, seneschal of Gascony, while the French were led by Géraut de Themines, governor of Limoges.

The battle that followed, totally ignored by English chroniclers, was described by the Chronica Majora of Limoges:

“In the same year, on the day following the feast of Saint Sixtus, the king of England's seneschal, who had come to the aid of the citizens of Limoges against the viscountess of Limoges, had a great victory over her army, between Aixe and the town of Limoges. He wounded and captured many of them, killing a nobleman and many others, without loss to him or his allies, at which the townsfolk rejoiced greatly. Moreover, they captured the banner of Girbert de Tamines. On the feast of Saint Laurence following [two days later] one of the viscountess's men was found dead and many horses on both sides too, but the viscountess lost many more.”*

The arms of William de Valence (1225-1296)

The arms of William de Valence (1225-1296)Edward I’s seneschal had won a battle for his master, and the bourgeois of Limoges celebrated their deliverance. On 27 August the king’s uncle, William de Valence, arrived with letters from Edward requesting the inhabitants of the town to swear an oath of fealty to him as Duke of Aquitaine. This went against previous judgements of the court of Paris, but the bourgeois agreed wholeheartedly. The service of the oath took place on 3 September, in the abbey of Saint-Martial, in the presence of the consuls and of all the community.

The fighting continued. On 16 September the bourgeois won another skirmish, and were so encouraged they decided to try a second attack upon Marguerite’s castle at Aixe. They marched on Sunday morning, with drums and trumpets, crossed the ford of Vienne and burnt the borough of Saint-Priest. They also roughed up the local priest and carried off the silver chalice, missal and candles from the church. At the gates of Aixe panic set in, and the mob fled in all directions, throwing away their weapons and hiding in the woods. A few days later Marguerite sent her men to burn the vineyards near Saint-Martial.

Edward could not move from Gascony. In September, even as war raged in the Limousin, Gaston de Béarn raised his head again.

*Thanks to Rich Price for the translation.

Published on January 17, 2020 04:28

January 16, 2020

Els Bels

Limoges and Béarn (1)

In 1273 the Limousin was a disputed land between France and Aquitaine, torn by an exceptionally bloody civil war. The commune of Limoges was on one side, and on the other the Viscomtesse Marguerite: she claimed the city was hers by right, while the commune argued they were not her men at all, but owed direct homage to the king of France.

Limoges

Limoges

Thrown into the mix was the Plantagenet claim to Limoges, left outstanding after the Treaty of Paris. There were suspicions in Paris that the commune preferred to be ruled by the English. A local annalist wrote:

“They [the French] hated us because…those who had raised the spirits of the King and of his advisers against us claimed wrongfully that we love the English best.”

King Philip ordered the Viscomtesse to stop attacking the people of Limoges. She ignored him and gathered an army at Chalusset, from where her soldiers rode to plunder, mutilate cattle, scatter wheat and perform “all kinds of wickedness.”

Philip seemed to cave to her pressure: at the Paris parlement of Pentecost 1273, he reversed his earlier decision and announced that the city of Limoges should give their homage to Marguerite. To add insult to injury, he ordered the citizens to release soldiers of the Viscomtesse they had taken prisoner, but did not order Marguerite to release her prisoners.

The enraged bourgeois of Limoges rose in arms and, on 5 July, attacked Marguerite’s castle at Aixe. They were thrashed out of sight by her troops and suffered terrible casualties. In desperation they now appealed to Edward I of England, who had gone from Paris to Gascony, and asked him to be their overlord. A fragment of their appeal survives (attached, second pic) expressed in the usual grovelling terms:

“To the most excellent lord Edward, by the grace of God, illustrious King of England, lord of Ireland and Aquitaine, king of the swingers, God-Emperor of Mars, high priest of all the things and rightful seigneur of sexy times…(etc etc)…”

Edward I & Eleanor of CastilePerhaps Edward couldn’t resist the notion of galloping to the rescue; he did technically have right on his side, since the French should have coughed up Limoges back in 1259. For the present he was too busy in Gascony, so he sent his wife Eleanor of Castile with an army of Gascons to help the bourgeous of Limoges.

Edward I & Eleanor of CastilePerhaps Edward couldn’t resist the notion of galloping to the rescue; he did technically have right on his side, since the French should have coughed up Limoges back in 1259. For the present he was too busy in Gascony, so he sent his wife Eleanor of Castile with an army of Gascons to help the bourgeous of Limoges.

Els Bels arrived on 25 July and was led in procession to Saint-Martial “with great honours”.

In 1273 the Limousin was a disputed land between France and Aquitaine, torn by an exceptionally bloody civil war. The commune of Limoges was on one side, and on the other the Viscomtesse Marguerite: she claimed the city was hers by right, while the commune argued they were not her men at all, but owed direct homage to the king of France.

Limoges

LimogesThrown into the mix was the Plantagenet claim to Limoges, left outstanding after the Treaty of Paris. There were suspicions in Paris that the commune preferred to be ruled by the English. A local annalist wrote:

“They [the French] hated us because…those who had raised the spirits of the King and of his advisers against us claimed wrongfully that we love the English best.”

King Philip ordered the Viscomtesse to stop attacking the people of Limoges. She ignored him and gathered an army at Chalusset, from where her soldiers rode to plunder, mutilate cattle, scatter wheat and perform “all kinds of wickedness.”

Philip seemed to cave to her pressure: at the Paris parlement of Pentecost 1273, he reversed his earlier decision and announced that the city of Limoges should give their homage to Marguerite. To add insult to injury, he ordered the citizens to release soldiers of the Viscomtesse they had taken prisoner, but did not order Marguerite to release her prisoners.

The enraged bourgeois of Limoges rose in arms and, on 5 July, attacked Marguerite’s castle at Aixe. They were thrashed out of sight by her troops and suffered terrible casualties. In desperation they now appealed to Edward I of England, who had gone from Paris to Gascony, and asked him to be their overlord. A fragment of their appeal survives (attached, second pic) expressed in the usual grovelling terms:

“To the most excellent lord Edward, by the grace of God, illustrious King of England, lord of Ireland and Aquitaine, king of the swingers, God-Emperor of Mars, high priest of all the things and rightful seigneur of sexy times…(etc etc)…”

Edward I & Eleanor of CastilePerhaps Edward couldn’t resist the notion of galloping to the rescue; he did technically have right on his side, since the French should have coughed up Limoges back in 1259. For the present he was too busy in Gascony, so he sent his wife Eleanor of Castile with an army of Gascons to help the bourgeous of Limoges.

Edward I & Eleanor of CastilePerhaps Edward couldn’t resist the notion of galloping to the rescue; he did technically have right on his side, since the French should have coughed up Limoges back in 1259. For the present he was too busy in Gascony, so he sent his wife Eleanor of Castile with an army of Gascons to help the bourgeous of Limoges.Els Bels arrived on 25 July and was led in procession to Saint-Martial “with great honours”.

Published on January 16, 2020 09:44

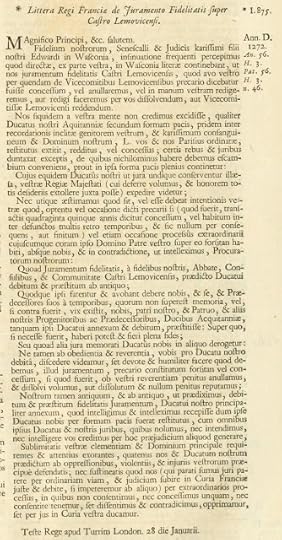

Vivat imperator Edwardus

“All the Anglo-French conflicts, during the end of the 13th century, resulted from the Treaty of Paris as necessary consequences.”

- Charles Victor Langlois, biographer of Philippe le Hardi

The Hundred Years War is generally thought to have started in the reign of Edward III and ended in the collapse of Plantagenet Aquitaine in 1453. It could arguably be backdated to the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris in 1259, whereby Henry III of England resigned most of his dynastic claims in France. He was left with the duchy of Gascony and a handful of other territories, which the French were reluctant to concede.

Specifically, the treaty stated that Louis IX would:

“give us and our heirs and our successors all the right that he has and holds in these three bishoprics and in the cities, namely, of Limoges, Cathors and Périgueux, in fief and domain…”

In October 1271, the ailing Henry III sent envoys to Paris to “ask and receive” the above lands, as well as Quercy, the Agenais and Saintonge. He also complained that French agents were harassing the officers of his heir, the Lord Edward, about the homage of the city of Limoges.

The new French king, Philippe le Hardi, put off the English envoys with vague answers. He was probably hoping for Henry to die, which he did on 30 November 1272.

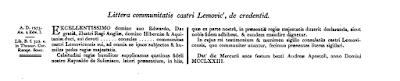

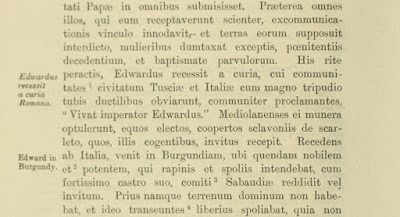

Henry’s successor was on his way back from the Holy Land. He landed in Italy in January 1273 and then passed through Lombardy; disturbingly (from a French point of view), the Italians and Lombards shouted “Long live the Emperor Edward!” The Milanese gave him gifts of horses, and on 25 June the Count of Savoy swore homage to the young English king. A lord of the kingdom of Arles, who had plundered the English army on its way to the Holy Land, was also brought before Edward and made to swear homage and fealty.

Edward then descended from the mountains of Burgundy and took part in a chaotic tournament at Chalons, where he humiliated the Comte d’Auxerre in single combat and set fire to the town. His truimphal procession ended in Paris, where he knelt before Philip and swore homage for his lands in France. Like his father, Edward was perfectly aware that the French had not fulfilled their side of the Treaty of Paris. For that reason he couched the oath in ambiguous terms: he did homage for all the lands he held of Philip, as well as the lands he ought to hold:

“Dominus rex fado vobis homagium pro omnibus terris, quas debeo tenere de vobis.”

- Charles Victor Langlois, biographer of Philippe le Hardi

The Hundred Years War is generally thought to have started in the reign of Edward III and ended in the collapse of Plantagenet Aquitaine in 1453. It could arguably be backdated to the aftermath of the Treaty of Paris in 1259, whereby Henry III of England resigned most of his dynastic claims in France. He was left with the duchy of Gascony and a handful of other territories, which the French were reluctant to concede.

Specifically, the treaty stated that Louis IX would:

“give us and our heirs and our successors all the right that he has and holds in these three bishoprics and in the cities, namely, of Limoges, Cathors and Périgueux, in fief and domain…”

In October 1271, the ailing Henry III sent envoys to Paris to “ask and receive” the above lands, as well as Quercy, the Agenais and Saintonge. He also complained that French agents were harassing the officers of his heir, the Lord Edward, about the homage of the city of Limoges.

The new French king, Philippe le Hardi, put off the English envoys with vague answers. He was probably hoping for Henry to die, which he did on 30 November 1272.

Henry’s successor was on his way back from the Holy Land. He landed in Italy in January 1273 and then passed through Lombardy; disturbingly (from a French point of view), the Italians and Lombards shouted “Long live the Emperor Edward!” The Milanese gave him gifts of horses, and on 25 June the Count of Savoy swore homage to the young English king. A lord of the kingdom of Arles, who had plundered the English army on its way to the Holy Land, was also brought before Edward and made to swear homage and fealty.

Edward then descended from the mountains of Burgundy and took part in a chaotic tournament at Chalons, where he humiliated the Comte d’Auxerre in single combat and set fire to the town. His truimphal procession ended in Paris, where he knelt before Philip and swore homage for his lands in France. Like his father, Edward was perfectly aware that the French had not fulfilled their side of the Treaty of Paris. For that reason he couched the oath in ambiguous terms: he did homage for all the lands he held of Philip, as well as the lands he ought to hold:

“Dominus rex fado vobis homagium pro omnibus terris, quas debeo tenere de vobis.”

Published on January 16, 2020 06:59