David Pilling's Blog, page 2

February 8, 2025

Special guest post by Sarah Tanburn

THE STORIES WE TELL ABOUT OURSELVES: fables for a future Wales

By Sarah Tanburn

‘We are the people and Cymru is our fortress.’

Children of the Land, my Welsh fantasy novella collection, closes with this line. The five tales are all set in the same not-far-off future Wales but with different characters. Along with monsters of land and sea and some battle-ready heroines, you will find climate change, geopolitics and world trade, and the independence of a small and ancient nation in the mix.

Why should a history blog, albeit with its wonderful focus on Wales, be interested in a bit of futuristic speculation? There is of course the Churchillian shibboleth that ‘those who don’t study history are doomed to repeat it.’ As I write, in February 2025, there is much to consider in that statement. Nonetheless, it was not my starting point.

In Wales, as artists, writers and activists, we tend to look backwards. History here is written in stone and blood. Castles bestride the landscape, instilling shock and awe across the centuries. Industrial detritus scatters the hills, from ancient slate quarries to a pit 200m deep outside Merthyr Tydfil where Ffos-y-fran mine finally stopped digging less than 18 months ago. The glorious, mythologised past haunts us too. The Mabinogion stories are reworked again and again, while Owain Glyndŵr and his successors are the heroes of many a novel – though we are yet to get a genuine biopic rooted in Wales.

‘Ahead of her, light’

‘Ahead of her, light’

The Fortress is the fifth of the tales in the book. Its heroine, Mwyn, is abandoned in the tunnels below the Clwyd Mountains. She finds a cavern, and within it, minerals which will change everything.

In Children of the Land, I explore a future Wales. How, I wondered, do we take all that weight and imagine our children’s lives? I didn’t want to think about policy, nor am I a Welsh nationalist; at most I am indy-curious. I asked myself what might have become of those monsters of legend. The murderous hawks of Arthur’s Court or the afancs said to haunt several lakes. If the land itself took a part, what kind of country might we become?

The result is five novellas set in very specific places. In the 2020 lockdown, writing Bones and Fire, I sent a friend to stand in the field where Dai burns her corpses and check you cannot see Worm’s Head. Twyn Dysgwylfa, the place of seeing, where Adain releases the hawks of dust and wine, is just north of Trallong. Old Nine Eyes basks in the sun in Sôr Brook, which winds through the hills west of Carleon.

Yet this imagined Cymru is isolationist and corrupt. The Aberystwyth government is happy to support almost any venture which will bring in hard currency but censors electronic correspondence. My heroines do business in ways which reveal the changing world: Korea is united but America has become simply geography. Desperate people in Senegal will pay handsomely for turtle meat harvested in the Menai Strait, and China owns power generated in English rivers.

The people of Cymru, like most of us, are content with life if left alone. The rich, the determined and the fluid, as they always have, will find a way to travel but in general people are content to stay where they are: it is a dangerous world out there. Children of the Land does not portray any idealised Celtic romance but neither is it straightforward dystopia.

‘I ignored her history as another contraction rippled through me’

Enfys, the narrator of The Flow, cannot afford to listen to an unqualified assistant as labour begins. We tend to ignore history in the making of anything new, yet value true experience as the crisis hits.

These novellas, which I subtitled Fables for a Future Wales, aims to learn from the stories we tell about ourselves. Some of those are fantasies, possibly rooted in our natural world, our farming or mining past, but filled with magic and blood. Others, still gory, of course are part of the documented record. Any future is messy and compromised, but let it be both informed and imagined, brought into being with true intention together with our dreams.

Children of the Land is available from all good bookshops or online. At this time, it is only published in print, and not electronically.

February 7, 2025

Prince(s) of Wales

#OTD in 1301 Prince Edward of Caernarfon was granted the royal lands in Wales and the lordship of Chester at the Lincoln parliament.

It is generally supposed that he was granted the title of Prince of Wales. However, no title was attached at this stage. Nor was he presented to the Welsh as a newborn infant who ‘could speak no Welsh’. In reality Edward was sixteen years old.

Although there was no recorded investiture ceremony, Edward began to be referred to as Prince of Wales from spring 1301. This seems to have been related to the Scottish campaign of that year, in which he was placed in command of 7000 Welsh and Irish troops at Carlisle.

Those Welshmen who swore homage to the prince were mostly drawn from the ‘uchelwyr’ or gentry class. Many of these, such as Morgan ap Maredudd and Gruffudd Fychan, had stepped forward to fill the power vacuum in Wales after Edward I destroyed most of the princes.

As such they were despised as upstarts by the remaining princely families and their heirs. A later poet, Gruffudd Llwyd, composed the following savage ‘cywydd’ to his patron, Owain Glyn Dwr:

“Aml iawn gan y mileiniad

Ariana ac aur, no rent ged,

A golud, byd gogaled;…

A fu isaf ei foesau

Uchaf yw, mawr yw’r och fau:

A’r uchaf cyn awr echwydd

Isaf ac ufuddaf fydd,

Hyn a wna, hen a newydd,

Y drygfyd. Pa raw fed fydd?”

(The villeins often have silver and gold - they bear no gifts - and riches, a niggardly world; he whose manner of living was lowest is now the highest, loudly do I bewail it, and the highest before midday will be the lowest and the most obedient. This is what makes, old and new, an evil world. What is this world coming to?)

Glyn Dwr was also a member of the Welsh gentry or squirearchy, but claimed descent from the ancient royal houses of Powys Fadog, Gwynedd and Deheubarth. This in turn justified his claim to the title of Prince of Wales. He was also descended of the Lestranges of Knockin, a Marcher dynasty who played a key role in the Edwardian conquest of Wales, but didn’t make much of that.

Sources:

The Merioneth Lay Subsidy Roll 1292-3 edited with introduction by Keith Williams-Jones

Edward I by Michael Prestwich

Medieval Wales c.1050-1332: Centuries of Ambiguity by David Stephenson

Leo the Thracian

Also on this day, in 457, Leo I 'the Thracian' became Eastern Roman Emperor. He was apparently placed on the throne by Aspar, a general who had played kingmaker for the past few decades. At first Leo was his puppet, but then turned the tables and had Aspar killed along with his eldest son, Ardabur.

Leo's 17-year reign was a mixed bag of successes and failures. The worst disaster was a naval expedition against the Vandals in 468, when his brother-in-law Basiliscus managed to lose the entire Roman fleet. Oops.

The emperor also issued an edict condemning army officers who practiced pagan sacrifice. Those of high rank were demoted and had their goods confiscated, while the lower ranks were tortured and condemned to labour in the mines.

Leo died in 474, aged 73, and is commemorated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

February 4, 2025

A Red Comyn at Roslin

24 February 1303 witnessed the battle of Roslin in Scotland. This was a victory for the Guardians of Scotland, led by John 'the Red' Comyn of Badenoch and Simon Fraser, and a much-needed morale booster at a grim time for the Scots.

The Scottish wars had been raging since 1296, when Edward I invaded and deposed his vassal, John Balliol, King of Scots, later known as 'Toom Tabard' or the Empty Coat. Edward hurriedly imposed an administration and then raced back south to rescue his duchy of Gascony from the French. Within months, however, his colonial government in Scotland was in trouble. A full-scale revolt erupted, under the leadership of Andrew Moray and William Wallace.

By 1303 Moray was dead and Wallace little more than a fugitive. Leadership of the Guardians passed to John Comyn and his ally Fraser, who had once served Edward and fought on the English side at the battle of Falkirk. Such changes of allegiance were far from uncommon in the medieval era.

Comyn had proved an effective war-leader, holding the English at bay with inspired guerilla-style tactics. Edward was hampered by his war with France, but in 1303 he was able to negotiate a final peace with the French. This in turn enabled the English king to focus all his resources on Scotland.

Before coming north with the main army, Edward sent a force under John Segrave and Robert Clifford to reconnoitre. It was ambushed at Roslin in Mid-Lothian, apparently due to the treachery of a certain 'boy', whom Comyn had placed as a spy in the English camp.

The battle itself was a running skirmish, in which each of the three divisions of the English force were attacked and defeated in turn. Later Scottish chroniclers claimed that thousands of Englishmen were slaughtered, although the casualties were probably in the low hundreds. Chroniclers on both sides of the border (and everywhere else) routinely exaggerated battlefield casualties.

Nonetheless, whatever the actual scale, Roslin showed the Scots they could defeat the English in open battle. In the short term it made little difference to Edward's plans. Apart from ransoming Segrave, captured in the fight, he carried on with his preparations and invaded Scotland in the autumn.

This campaign ended with the surrender of the Guardians and what appeared to be a permanent reconquest of Scotland. Within two years, however, the Scots were once again in revolt under Robert de Bruce, and Edward's attempted settlement fell to pieces. He would die in 1307 in the Cumbrian marshes, with Scotland just out of reach.

There was a grim postscript to Roslin. One of the English captives was Ralf de Cofferer, a clerk of the English treasury. Fraser gave Ralf a furious lecture, accusing him of embezzling Fraser's wages when the Scot was in Edward's service. He was then murdered by one of Fraser's servants or 'ribalds', his hands cut off and left to bleed to death in the forest. It was hell in the diplomatic, as they say.

Attached is a movie still of Comyn and Bruce at their famous meeting at Dumfries in 1306, shortly before Comyn aggressively fell on Bruce's knife.

February 3, 2025

A street battle in Flanders

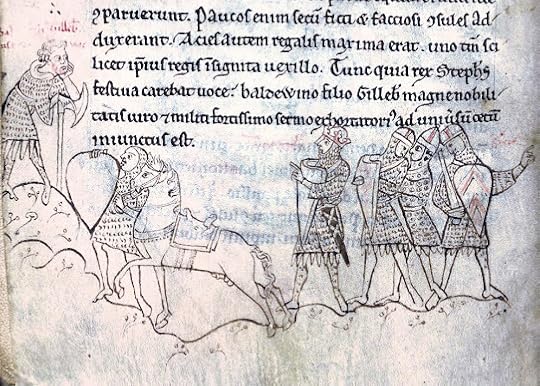

Manuscript image of a Welsh archer

Manuscript image of a Welsh archer#OTD in 1298 a riot blew up at Ghent in Flanders, when the soldiers of Edward I clashed with the Flemings.

The king's army had been billeted at Ghent since the previous September. He was in Flanders to help his ally, Count Guy Dampierre, fight the French. Unfortunately their soldiers were more interested in fighting each other.The sources of this tension are unclear. English chroniclers blamed the Flemings for the riot, and claimed they had entered into a conspiracy with the French to kidnap Edward. Flemish writers claimed that Edward's Welsh and English footsoldiers (mostly Welsh) were out of control, attacking and robbing Flemish citizens.

On balance, the Flemish version of events is more likely. Welsh infantry were notoriously undisciplined, and had a bad habit of attacking civilians: they behaved the same way in Scotland, Norway, Ireland, Gascony, England, or wherever else Welsh troops were deployed. One of Edward's officers even refused to lead Welshmen into Scotland again, unless he was given a guarantee of immunity from prosecution.

Edward himself had gone off to Brabant, to visit his daughter and negotiate a trade deal with his son-in-law, Duke Jan. He returned to Ghent in time to witness the riot, which erupted into a full-scale street battle.

Things only quietened down when Edward threatened to hang all of his infantry. He was talked out it by Antony Bek, Bishop of Durham, but the people of Ghent demanded compensation. When the king's army left the city, a few days later, every footsoldier was thoroughly searched before he was allowed to pass through the gates.

February 2, 2025

Overbearing lords

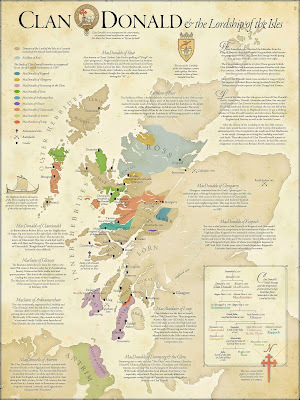

In February 1293 John Balliol, King of Scots, appointed two new sheriffs in north-west Scotland. These were William earl of Ross, sheriff of Skye, and Alexander Argyll, sheriff of Lorn.

Ross and Argyll had supported Balliol's claim to the kingship, so he was sensibly trying to appoint loyal men to important posts in Scotland. However, the policy ran aground when Argyll clashed with another leading Isleman, Angus Mor.

To undercut his rival, Angus refused to swear homage to Balliol as King of Scots and took his complaint to Balliol's overlord, Edward I. He died shortly after, but his son Alexander also refused to acknowledge Balliol and complained to Edward. In response Balliol confiscated his land, but the case was still ongoing when war broke out with England in 1296.

The Argyll/Mor affair exposed Balliol's weakness as King of Scots. Because he had sworn homage to Edward as superior lord, his subjects had somewhere else to go if they didn't like Balliol's justice. In other words, they could bypass the justice of his court and appeal to Westminster.

Argylle was not the only Scot to do this. Bishop Wishart of Glasgow and MacDuff of Fife also appealed to Edward over Balliol's head, while the Bruces openly defied him. Whatever his character flaws, it is difficult to see how Balliol could have succeeded.

Interestingly, Edward had the exact same problem in his role as Duke of Aquitaine (also called Gascony or Guyenne) in south-west France. After the Treaty of Paris in 1259, he and his heirs were vassals of the Capetian kings of France. His Gascon subjects reacted in the same way as the Scottish appellants, bypassing the ducal court and submitting appeals to Paris.

The result was an impossible situation, in which neither Gascony or Scotland could be governed effectively. It didn't help that both Edward and his cousin, Philip the Fair of France, were typically overbearing overlords who sought to exploit every advantage.

(Incidentally, I don't know if the attached map of Scotland is particularly accurate, I just like it).

Equal to a thunderbolt

On this day in 1141 King Stephen was defeated and captured at the Battle of Lincoln. Roger of Hoveden gives a vivid account of his capture:

"Then was seen the might of the king, equal to a thunderbolt, slaying some with his immense battle-axe, and striking others down.

Then arose the shouts afresh, all rushing against him and him against all. At length through the number of the blows, the king's battle-axe was broken asunder. Instantly, with his right hand, drawing his sword, well worthy of a king, he marvellously waged the combat, until the sword as well was broken asunder.

On seeing this William Kahamnes [i.e. William de Keynes], a most powerful knight, rushed upon the king, and seizing him by the helmet, cried with a loud voice, "Hither, all of you come hither! I have taken the king!"

Stephen was said to be a mild man, soft and good, who did no justice, but none every doubted his courage. Lincoln resolved nothing: later in the year he was exchanged for Robert of Gloucester, the Empress Maud's half-brother, and the war rattled on.

Attached is a near-contemporary image of the battle from the Historia Anglorum.

February 1, 2025

The outlaw of Sherwood

In February 1272 Roger Godberd, a notorious outlaw, was hunted down and captured by Reynold Grey, High Sheriff of Nottingham. He was held in prison for four years and finally stood trial at Newgate in April 1276.

At his trial, Godberd produced charters of Henry III, which pardoned him of all offences. However, these documents only applied to his first period of outlawry before October 1266, and the Dictum of Kenilworth. They did not cover his second term as an outlaw between 1269-72.

In normal circumstances Godberd would have been executed. His lieutenant, Walter Devyas, was beheaded in 1272, and by rights Godberd should have gone the same way.

Instead he walked free. Godberd was still alive and kicking in 1287, when he was briefly imprisoned again for poaching in Sherwood Forest. Ironically, one of his fellow poachers was Reynold Grey, the former sheriff.

The former outlaw died in the 1290s, apparently of natural causes. His son, Roger junior, was allowed to inherit the tenancy of Swannington manor, now in the possession of Edmund of Lancaster.

The king, Edward I, had an interesting relationship with these outlaws. Back in 1269, before going on crusade, he had arranged a pardon for Godberd's ill-fated lieutenant, Walter Devyas. This proved unwise, as Devyas immediately resumed a life of violent crime. When he was recaptured, in 1272, there was no mercy.

Godberd probably owed his salvation to the king. At the start of his reign, Edward I wished to settle England as soon as possible, and knew that could not be achieved with a round of bloody executions. One of his first parliaments issued a general pardon to all of Simon de Montfort's surviving followers, which probably explains Godberd's survival.

(Yep, I am pimping one of my books again).

January 31, 2025

Drake - Tudor Corsair!

Inspiration to write Drake – Tudor Corsair, by Tony Riches

I was born within sight of Pembroke Castle, but only began to study its history when I returned to the area as a full-time author. I found several accounts of the life of Henry Tudor, (who later became King Henry VII and began the Tudor Dynasty) but no novels which brought the truth of his story to life.

The idea for the Tudor Trilogy occurred to me when I realised Henry Tudor could be born in book one, ‘come of age’ in book two, and rule England as king in book three, so there would be plenty of scope to explore his life and times.

I’m pleased to say all three books of the Tudor trilogy became best-sellers in the US and UK, and I decided to write a ‘sequel’ about the life of Henry VII’s daughter, Mary Tudor, who became Queen of France. This developed into the Brandon trilogy, as I was intrigued by the life of Mary’s second husband, Charles Brandon, the best friend of Henry VIII. The final book of the Brandon trilogy, about his last wife, Katherine Willoughby, has also become an international best-seller.

Katherine saw Elizabeth I become queen, and I began planning an Elizabethan series, so that my books tell the continuous stories of the Tudors from Owen Tudor’s first meeting with Queen Catherine of Valois through to the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign.

I decided to show the fascinating world of the Elizabethan court through the eyes of the queen’s favourite courtiers, starting with Francis Drake. I’ve enjoyed tracking down primary sources to uncover the truth of Drake’s story – and discovering the complex man behind the myths.

I’ve found a wealth of primary sources on the life of Francis Drake, including first-hand accounts from Drake and those who sailed with him – but they are all written from their own point of view.

These sources often contradict each other, even with the names of places and ships. Part of this is deliberate, as Drake had to take care not to reveal that the queen’s hand was on his tiller, and even his chaplain used code names to refer to crew members.

I remember being taught that Drake was the first man to sail around the world, and that he nonchalantly played a game of bowls as the Spanish Armada sailed up the British Channel in 1588.

It’s true that Drake recreated the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation – becoming the first British captain to sail around the world. Unlike Magellan, Drake survived being attacked by hostile islanders, and lived to tell the tale.

As for his game of bowls, there was a bowling green at his manor house, but the story first appeared thirty-seven years after the Armada. From what we know of the tide and weather on that day, Drake’s casual behaviour may well have been justified, but I believe it’s all part of the myth around Drake’s life, which he had good reason to encourage.

Francis Drake was a self-made man, who built his fortune by discovering the routes used by the Spanish to transport vast quantities of gold and silver. He had a special relationship with Queen Elizabeth, and they spent long hours in private meetings, yet was looked down on by the nobility even after he was knighted. His story is one of the great adventures of Tudor history.

Tony Riches

Author Bio

Tony Riches is a full-time UK author of Tudor historical fiction. He lives with his wife in Pembrokeshire, West Wales and is a specialist in the lives of the early Tudors. As well as his new Elizabethan series, Tony’s historical fiction novels include the best-selling Tudor trilogy and his Brandon trilogy, (about Charles Brandon and his wives). For more information about Tony’s books please visit his website tonyriches.com and his blog, The Writing Desk and find him on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky and Twitter @tonyriches.

Drake – Tudor Corsair is available in paperback and eBook and audible editions from:

Amazon US https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08FCTYQF4

Amazon UK https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B08FCTYQF4

Amazon CA https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B08FCTYQF4

Amazon AU https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B08FCTYQF4

Author Links:

Website: https://www.tonyriches.com

Writing blog: https://tonyriches.blogspot.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/tonyriches

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/tonyriches.bsky.social

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tonyriches.author

Podcasts: https://tonyriches.podbean.com

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/5604088.Tony_Riches

January 30, 2025

The not-very famous battle of Bellegarde

#OTD in 1297 the army of Edward I was defeated by the French at Bellegarde or Bonnegarde in southern Gascony. This was a bad start to a difficult year for the king, in which his forces suffered a more famous defeat at Stirling Bridge in Scotland, and he faced serious political opposition in England.

The Anglo-Gascon army was led by Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. He was on his way to resupply Bellegarde, when he marched into a carefully laid French ambush in a wooded valley near the town. Lincoln might have been betrayed by a scout, though the sources are unclear.

Lincoln’s army was formed into three divisions. The first was led by John de St John, a former seneschal of Gascony. When the French appeared, he charged straight at them, apparently to try and give the rest of the army a chance to escape. After a hard fight, St John was captured and spent the next few years in a French prison.

The second and third divisions were quickly routed, although Lincoln managed to rally some of his knights and lead a desperate charge to try and kill the French commander, the Comte d’Artois. He couldn’t break through, and only nightfall saved the remains of his army. Lincoln spent the night wandering alone in a forest, while many of his knights were killed or captured.

Bellegarde was a very serious defeat: Lincoln had lost the only English field army in Gascony, which left the remaining Plantagenet strongholds exposed to attack. This explains Edward’s frenzied efforts to get over to Flanders later in the year, to split the French and lift the intense pressure on Gascony.

All this occurred at the same time as the revolt of Andrew Moray and William Wallace in Scotland. To save his beloved duchy, the last significant piece of the so-called Angevin Empire, Edward was quite prepared to let Scotland (or even England) go to blazes. Gascony came first.

However, these set-piece battles rarely proved decisive. Only a few weeks later, in February, the French agreed to a truce, suspending military operations. This gave the English time to ferry over supplies to the ducal bastions in Gascony, which held out until the duchy was formally restored to Edward in 1303.

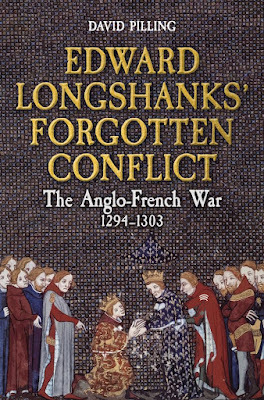

On a side-note, I wrote a book about all this, which nobody bought. Screw it, then: the next one will be all about Wallace’s mum.