David Pilling's Blog, page 6

March 23, 2022

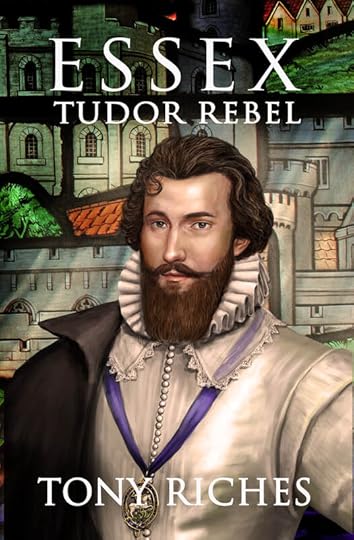

Special guest post by Tony Riches, author of Essex: Tudor Rebel

ESSEX - Tudor Rebel (Book 2 of the Elizabethan Series)

🇺🇸 Amazon US: https://amazon.com/dp/B09246T7ZT

🇬🇧 Amazon UK: https://amazon.co.uk/dp/B09246T7ZT

Tell us about your latest book

Essex - Tudor Rebel is the second book of my Elizabethan series, and follows the story of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. A favourite of the queen, he was impetuous, irreverent, ambitious and charming. Some people suggest they were lovers, yet in truth he was more like the son Elizabeth never had. Elizabeth offered power, wealth, influence and status, while Robert’s attention made her feel young and attractive. The events leading up to his surprising ‘rebellion’ took a lot of research, but I believe my account is as factual as possible.

What is your preferred writing routine?

I’m an early riser and sometimes wake with entire passages of dialogue in my head which have to be written down. I write biographical fiction about the Tudors and Elizabethans, and over the years I’ve developed a system of writing one book a year. I research the person chosen for my next book during the summer, visiting actual locations and tracking down primary sources. I write throughout the autumn and winter, then send my book to my editor in the spring, for publication before the summer.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

If you can write just one page a day, that’s a book a year. It’s important to read the work of writers you admire, and learn from them.

What have you found to be the best way to raise awareness of your books?

Keep trying different things to reach new audiences. For example, I started a podcast, ‘Stories of the Tudors’ (https://tonyriches.podbean.com/) to talk about the research behind my books, and include excerpts from my audiobooks. (I’ve had over 156,000 downloads, which is encouraging.)

Tell us something unexpected you discovered during your research

When I was researching the early life of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, I was amazed to find he lived for some years at Lamphey Palace, twenty minutes from my home in Pembrokeshire.

What was the hardest scene you remember writing?

I was saddened to write about the execution of Owen Tudor, after spending so long studying every detail of his life. When Owen was led out into the market place at Hereford, he hoped to be pardoned, until he saw the executioner, waiting with an axe.

What are you planning to write next?

The manuscript of my new book, Raleigh – Tudor Adventurer, the third book of my Elizabethan series, is with my editor and will be published before the summer. I am now researching three books about Queen Elizabeth’s Ladies-in-waiting. The three I’ve chosen are rarely mentioned, yet were present at many of the key events of the Elizabethan era, and their stories deserve to be told.

Tony Riches

About the Author

Tony Riches is a full-time UK author of best-selling historical fiction. He lives in Pembrokeshire, West Wales and is a specialist in the lives of the Tudors. He also runs the popular ‘Stories of the Tudors’ podcast, and posts book reviews, author interviews and guest posts at his blog, The Writing Desk. For more information about Tony’s books please visit his website tonyriches.com and find him on Facebook and Twitter @tonyriches

Links:

Blog: https://tonyriches.blogspot.com/

Website: https://www.tonyriches.com/

Podcast: https://tonyriches.podbean.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/tonyriches

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tonyriches.author

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tonyriches.author/

Amazon Author Page: https://www.amazon.com/author/tonyriches

Published on March 23, 2022 03:57

March 22, 2022

Hands across the North Sea (5)

When Alv Erlingsson returned to Norway in 1286 with English mercenaries and 2000 marks in English silver, he was at the height of his power. He had recently been made an earl (or jarl) and played a leading role in Norwegian policy against Eric Klipping, the king of Denmark.

When Alv Erlingsson returned to Norway in 1286 with English mercenaries and 2000 marks in English silver, he was at the height of his power. He had recently been made an earl (or jarl) and played a leading role in Norwegian policy against Eric Klipping, the king of Denmark.Then it all went very wrong. He came home to discover that Norway and Denmark had peace in his absence, which meant there was no longer any need for the English soldiers and money. If he was sensible, Alv would have sent his English assets back home and settled into the peace.

So, naturally, he did no such thing. The Norse annals of this period describe a bitter private war that blew up between Alv and Haakon, Duke of Oslo and heir to the Norwegian throne. Alv, or some of his men, captured Haakon's seneschal, Hallkjell Krøkedans, and put him to death. This provoked a furious response: 220 of Alv's men were hunted down and killed, while he was forced to abandon Norway and live as an outlaw.

Alv's brother, Theodore, appealed to Edward I to let the fugitive claim asylum in England. Theodore's letter (kindly translated by Rich Price) is a masterpiece of obsequious grovelling:

“To his most excellent and illustrious lord, Edward, by the grace of God king of England, lord of Ireland, duke of Aquitaine: Theodore of Tønsberg, baron of the illustrious king of Norway, though unworthy, stands ready and prepared to give him service and honour.

Your excellency's fame, the increase of which is everywhere acknowledged in the most justified praise, shines forth very brightly and on manifold occasions has encouraged and induced my insignificant self to thus boldly offer my service to your lordship in these present letters. I humbly and earnestly entreat your noble excellency that, if it please you, you might deign to accept me as your knight; I shall faithfully fulfil most eagerly and devotedly any purpose in my land which may please you and is within my power, whilst upholding the honour due to my lord the king of Norway.

Furthermore, trusting in your abundant mercy, I humbly and earnestly beseech that through [that clemency] you extend to me more of your grace than the unworthiness of my lowly status might merit from such a request, but, if it should happen that a certain knight, my brother Oliver, who was condemned to exile by my lord the king of Norway for a homicide he committed, should have recourse to your domain, [I beg] that your royal majesty deign to grant him aid, so that through the mediation of your guidance and that assistance he may achieve a peaceful reconciliation and the grace of my lord the king. If it please you, the bearer of these present letters, your loyal man Richard, will inform you more clearly of other matters on my lowly behalf.”

Theodore had good reason to butter Edward up. His brother had absconded with the 2000 marks in English silver: this meant that Norway could no longer pay war damages to the German towns in the Baltic, which left them in breach of the truce. It also meant that Edward would not get his money back, and the kingdom of Norway would be excommunicated.

Published on March 22, 2022 06:44

March 21, 2022

Hands across the North Sea (4)

In 1286 Alv Erlingsson came to England and borrowed the sum of 2000 marks (about £1600) from Edward I. He also gained permission from the king to enlist English mercenaries from the Cinque Ports.

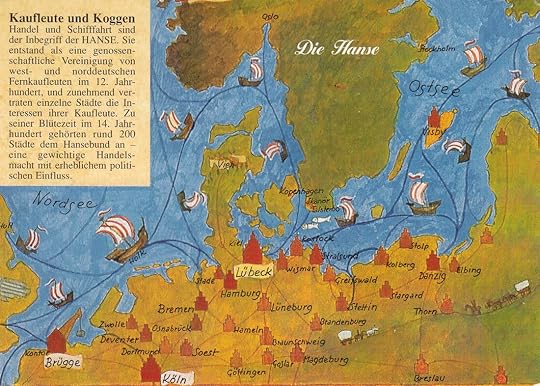

In 1286 Alv Erlingsson came to England and borrowed the sum of 2000 marks (about £1600) from Edward I. He also gained permission from the king to enlist English mercenaries from the Cinque Ports.It was once thought that the cash was supposed to pay the mercenaries. Recent research by Tore Skeie, a Norwegian historian, has discovered the money was really meant to pay off war damages owed by Eric III of Norway to certain German or 'Wendish' towns on the German/Baltic coast. The most important of these was Lubeck, and the towns would later form the famous Hanseatic League.

The war between Norway and Lubeck had erupted in 1284, when the Norwegians imposed restrictions on merchants from the north German ports. In response, Lubeck and the other grain-exporting towns imposed a naval blockade on Norway.

Both sides appealed to Edward I for military aid. In February 1285 Duke John I of Saxony asked the English king for help; over a year later, 7 March 1286, Eric III of Norway did the same. Unlike his grandfather, King John, who had sent Welsh troops to Norway, Edward opted to stay out of it.

Eventually the Norwegians were forced to sue for peace, and accept the arbitration of the King of Sweden. Via the final peace agreement, Norway had to lift the restrictions on German trade and agree to pay an indemnity of 6000 Norwegian marks or 2000 marks of English silver.

This was the sum loaned from Edward by Alv Erlingsson in 1286, during the latter's trip to England. It seems Edward wanted peace among the Nordic kingdoms, and was prepared to pay for it.

Not that he was a charity. Edward made it clear, on threat of excommunication, that he wanted his money back inside 24 months.

Fat chance.

Published on March 21, 2022 06:27

March 19, 2022

Hands across the North Sea (3)

In June 1286 Edward I issued a power of attorney to one Riccardus Guiditioniis, a merchant of Lucca based in Tuscany. The power of attorney authorised Riccardus to pay 2000 marks in English sterling to Alv Erlingsson 14 days after the upcoming Saint Mikkelsdag (29 September).

In June 1286 Edward I issued a power of attorney to one Riccardus Guiditioniis, a merchant of Lucca based in Tuscany. The power of attorney authorised Riccardus to pay 2000 marks in English sterling to Alv Erlingsson 14 days after the upcoming Saint Mikkelsdag (29 September).This loan was short-term only. A month later Alv was in London, where he agreed to repay the money in two instalments; one by September 1287, the second by September 1288 at the latest. If Alv defaulted then he would be excommunicated. So would his master, the King of Norway, and his heirs.

Alv was also permitted to enlist soldiers in England, to provide Norway with military assistance against Denmark. We happen to know where these soldiers came from, thanks to a brief line in Gottskalk's annals, a modern collection of Icelandic annals contained in a parchment manuscript in the Royal Library of Stockholm. The line reads:

1286: […] Komv Tartarer j Noreg oh Hugi nuncius og Fiportungar med herra Alfi.

This says that Alvi returned to Norway with men of the 'Fiportungar', which translates as Five Ports i.e. the Cinque Ports of Hastings, Sandwich, Deal, Rye and Winchelsea. The barons of the Cinque Ports were notorious pirates and freebooters, so it made sense for Alv to recruit them for an expedition to Denmark. Plus, from Edward's perspective, it got them out of the way for while.

The annal also refers to 'Komv Tartarer', which means Tartars or Mongols. We know from other Icelandic chronicles that Arghun Khan, fourth ruler of the Mongol il-Khanate, sent diplomats to the court of King Eric Magnusson at this time, as well as other Christian courts. It's a long way from the steppes to the fjords, boys.

All of the above took place soon after the death of Alexander III of Scotland, who plunged off a cliff in March 1286. He left only one heir, the famous Maid of Norway. Edward is not generally thought to have shown any particular interest in Scotland for several years after Alexander's demise. However, his willingness to provide military and financial aid to the Maid's father, Eric II, may imply he was already speculating on Scotland's future.

Published on March 19, 2022 04:28

March 15, 2022

Hands across the North Sea (1)

One fine evening in 1250, King Erik IV of Denmark was playing at dice with some of his knights, at a house in Gottorp in Schleswig. A good time was being had by all, until some men burst in, dragged the king outside and into a waiting boat. Erik was rowed out onto the river Schlien, and then beheaded with an axe. His body was dumped in the river. The next morning, some fishermen dragged it out and carried it to the local Dominican abbey; the headless corpse was eventually laid to rest at St Bendt's Church, Ringsted.

One fine evening in 1250, King Erik IV of Denmark was playing at dice with some of his knights, at a house in Gottorp in Schleswig. A good time was being had by all, until some men burst in, dragged the king outside and into a waiting boat. Erik was rowed out onto the river Schlien, and then beheaded with an axe. His body was dumped in the river. The next morning, some fishermen dragged it out and carried it to the local Dominican abbey; the headless corpse was eventually laid to rest at St Bendt's Church, Ringsted.In 1286, thirty-six years later, a Norwegian envoy arrived in England. This was Alv Erlingsson, earl of Sarpsborg. Margaret, the daughter of King Eirik II of Norway, had just acceded to the throne of Scotland. Margaret was also the great-niece of Edward I of England.

Earl Alv went to the English court and informed the king of the assassination of Erik IV. This was very old news by 1286, but it had apparently been kept a secret for over three decades. Alv had been sent by his master, King Eirik II of Norway, to whip up English military support for a looming war between Norway and Denmark. The murdered king, Erik IV, had been Eirik's grandfather.

Edward's response to the news was, as Kathleen Neal described it, 'an extraordinary articulation of feudo-vassalic rhetoric that was rare in Edward's correspondence: indeed, it seems to have struck a personal chord'. The royal murder inflicted Edward with 'horror on the heart' – cordi nostro horrorem incussit – at which he described as a crime – sceleris – and an outrage 'flagitium'. The king's words, composed by a team of professional scribes but at his will and supervision, were a departure from the standard.

This was not just hot air. Edward instructed his brother, Edmund, to give licences to any English baron, knight or man-at-arms who wished to fight for the King of Norway against the Danes. In this instruction, the king wrote of the 'hateful' crime to all princes and noblemen, who all ought to rise up against it. To put his money where his mouth was, Edward also granted Earl Alv a war subsidy of 2000 marks sterling (about £1600). The English expeditionary force was to be dispatched from the Cinque Ports.

Published on March 15, 2022 06:45

March 14, 2022

Under the Hammer

This is a review of a new revised edition of Under the Hammer by Dr Fiona Watson, first published in 1999 and based on a PhD thesis.

This is a review of a new revised edition of Under the Hammer by Dr Fiona Watson, first published in 1999 and based on a PhD thesis. Harsh experience has taught me the folly of broaching Edward I and Scotland, especially on social media. Seven hundred years after the old brute turned up his toes, and the subject still has the power to provoke and enrage (although not titillate, alas). Much of it is bound up with modern politics, in which a clear red line is drawn between the medieval wars of Scottish independence and the current Holyrood vs Westminster storm. For those seeking useful villains, Edward Longshanks might have been cooked up in a laboratory.

Fiona Watson's books on Scottish history, and this era in particular, are a welcome refuge. Watson is a 'proper' historian i.e. one who leaves her prejudices and preferences at the door, and always places the subject first. She is also one of the few to have made an in-depth study of the towering piles of surviving contemporary evidence for Edward I's Scottish wars. Virtually all this material, as she acknowledges, was churned out by the English administration. Inevitably, this gives us a rather lop-sided view of events.

These records, by their nature, are a little dry. Those who seek an adrenaline-fuelled tale of glorious battles and patriotic heroes with lovely eyes may look elsewhere. Indeed, they are spoiled for choice. It is to Watson's credit that she manages to weave the dusty old rolls of supply and finance, prise and purveyance, wage rolls and whatnot into a compelling narrative.

This is the actual stuff of medieval warfare; the endless flow of wagons creaking northward, bowed under the weight of foodstuffs and chests of money (usually late); bored soldiers on garrison duty, wondering if their wives are playing away from home; teams of harassed, overworked clerks, staring glumly at the latest impossible demand from their royal master, who was apparently under the impression that fresh soldiers grew on trees. In this respect Edward's attitude resembled that of the Roman emperor, Justinian I, who was once advised by an unusually brave secretary to sow dragon's teeth in the soil. That way, an army might just pop out of the ground.

In a subject dominated by hyperbole, Watson is also a voice of common sense. This is a thankfully linear narrative, point A to point B, starting with the death of Alexander III in 1286 and ending in 1305, when it seemed that Edward had finally imposed his will on the Scots. He had not, of course, but like every good historian Watson is careful to point out the dangers of hindsight. We can all judge, and have a good old sneer at the ancient dead and their mistakes in life, from the comfort of our armchairs. Very few of us – hopefully – will ever have to deal with such challenges.

To begin at the beginning. In the immediate aftermath of Alexander's death, Edward showed no particular interest in Scotland. Then, the Guardians invited him to act as arbiter in the Scottish succession crisis. Alexander had left no male heir, only a young daughter, the Maid of Norway. Without outside intervention, civil war loomed. The main threat to the peace came from the Bruce faction, who had already started to attack their fellow Scots.

Edward was also the natural choice. He was not only Scotland's nearest neighbour, and the greatest power in the British Isles, but Western Europe's foremost statesman. Watson might have made a little more of this latter point. Ironically, for a king regarded these days as a war-monger, Edward was seen by many contemporaries as a mediator; one who could be relied on to pour oil on troubled waters. For instance, he had previously acted as a disinterested arbiter in Savoy, Sicily and the empire. Given Edward's status, and his record to date, the decision of the Guardians becomes more natural still.

Military conquest was not Edward's first choice, or even his second. If the Maid had lived, and married the future Edward II, the union of the two crowns would have taken place long before 1603. The Guardians, it should be said, had no objection to this plan. Alas, the girl died, and it was at this point that Edward crossed the Rubicon (or the Tweed).

The late Archibald Duncan, in his brilliant, extensive, migraine-inducing history of the kingship of Scotland, exposed Edward's tactics. Watson synthesises Duncan's argument with admirable clarity. The crucial point was the difference between arbitration and judgement. Essentially, an arbiter had to remain neutral. To act as judge on the succession, however, required Edward to first have possession – or 'sasine' – of the Scottish kingdom. As Watson states, Edward grasped this point long before the Scots did. One by one, the various claimants to the throne were coerced into accepting Edward as judge.

Even here, the king did not gain everything he wanted. Some years later, in 1296, Edward was obliged to put his case for Scotland before the pope. That case, Edward knew, looked weak on parchment. Without going into the excruciating details, the king ordered his clerks to doctor the paperwork. This was intended to show the Scots had agreed to Edward's sasine and overlordship in early June 1291, when they had not. Thus, his entire claim to Scotland was based on a tissue of lies and legal half-truths, backed up by threats and menaces.

One may condemn Edward for his disgraceful behaviour, but also deal in context. Watson points out that his conduct was not untypical. Kings and popes all over medieval Europe dealt in the same low methods. The eventual victor of the Scottish wars, Robert I, was no innocent; indeed, given what King Bob and his family got up to, he could be seen as the greatest PR man in British medieval history. As for Edward, his experience was paradoxical. At the same time as he chose to deceive the Scots, he was deceived by his overlord, Philip the Fair, over the duchy of Gascony. Watson is not the first to point out that the one situation almost reads like a sick parody of the other. There is no morality in high politics, then or now.

The war, when it came, was an avoidable tragedy. Edward at first sought to control Scotland via a puppet king, John Balliol. Poor Balliol, remembered as 'Toom Tabard' (Empty Coat) due to his alleged weakness, was caught between two fires. In other circumstances he might have made a fine king; as it was, he had to cope with Edward's constant meddling on the one hand, and the fractious magnates of Scotland on the other. His main rival was Robert de Bruce, known as the Competitor, grandfather of the victor of Bannockburn. Having done their best to start a civil war, the Bruces were prepared to do absolutely anything to seize the crown. That included dealing in forged documents – hello, this sounds familiar – and clambering into bed with Edward.

One key piece of evidence, not included here, is an astonishing letter from the Competitor to Edward, dated 1291. Bruce advised Edward to put aside all previous treaties and agreements between the two kingdoms, and simply take Scotland for himself. Come and get it, big boy. Having lost out to Balliol, the Bruces showed Edward a flash of thigh, in the hope he would come north, impose his overlordship, and plant a Bruce on the throne. It may be that his policy from 1291 was driven by this secret invitation, so Watson's decision to omit the letter is a flaw.

After several years of Edward's bullying, the Scots could endure no more and forged a secret alliance with Philip. This dragged Scotland into the pre-existing state of war between England and France (and, for that matter, Norway and Germany). The utter mendacity of everyone involved is a thing to behold. Another of Philip's allies, King Erik of Norway, pledged to send fifty thousand Danish soldiers to invade England. In the event, not a single Danish tourist set foot on English soil: Erik had already come to a secret understanding with Edward, and was simply trying to screw money out of Philip. It worked, too, so fair play.

Edward's reaction to the Franco-Scots alliance, when he learned of it, was one of utter fury. In summer 1296 he gathered a massive army, burst into Scotland and flattened Balliol's army inside a few weeks. The Scots had no chance: as Watson points out, they had not fought a proper war in decades, while Edward's ranks were packed full of veterans of Wales, Gascony and the Holy Land, as well as the civil wars in England. Here, again, more context would have been helpful. There is no doubt that Edward regarded this as part of a much wider campaign against his chief enemy, Philip: at the same time as he overran the Scottish Lowlands, his brother Edmund was leading a separate English army against the French in Gascony. That said, there is a danger of losing focus.

From this point, the book is really a blow-by-blow study of Edward's military campaigns in Scotland. Watson shows that the king fatally underestimated the depth of Scottish resistance. This was not simply due to his contempt for the Scots – though he had plenty of that to spare – but his concerns elsewhere. Watson refuses to indulge in the commonly held fantasy that Edward was 'obsessed' with Scotland, excluding all else. In reality he was far more compelled by the recovery of Gascony, the last substantial fragment of the Angevin Empire. To that end Edward had spent oceans of gold on stitching together a vast anti-French coalition in Germany and the Low Countries. By 1296, hampered by revolts in Wales and Scotland, he was two years late in joining his allies on the continent. Every moment he spent on Scottish soil was a costly distraction.

The problem of Gascony explains Edward's hastily cobbled-together administration in Scotland in 1296. Less explicable is his decision to ride roughshod over Scottish laws and customs, which virtually guaranteed rebellion. Yet, with her usual fairness, Watson points out that Edward was not entirely deaf to Scottish systems of government. For instance, he appointed three justiciars via the traditional Scottish format. By and large, however – with a few notable exceptions, such as the Earl of Menteith – he stuffed his new colonial government with Englishmen, then raced off south to grapple with cousin Philip.

What happened next is well-known. William Wallace raised his head, as did a great many fellow Scots who objected to the new English taxes and demands for military service. Those demands were also causing serious unrest in England, although here Watson leans on some outdated assessments. The notion that England was on the edge of civil war in 1297 has been seriously challenged in recent times, notably by Andy King. As King has shown, Edward's envoys had already come to agreement with the king's critics in late August. This was before the battle of Stirling Bridge in September. Thus, the argument that Wallace's victory ironically united the English political community is questionable.

Edward's victory at Falkirk in 1298, however much it soothed English pride, did little to re-establish his control over Scotland. In fact his position deteriorated, until by late 1299 things were looking seriously fragile. This, as Watson shows, was due to several factors. English supply lines were too extended, the money kept running out, and the Scots launched devastating counter-raids into the northern counties. Instead of confronting Edward's massive armies in the open, the Scots cut his supplies, terrorised the peasantry over the border, harried his garrisons in Scotland. Those garrisons were perpetually short of money and supplies, often little more than outposts in the middle of hostile territory.

This is a very different picture from the traditional 'Hammer of the Scots' image, in which the mighty Plantagenet warlord swept all before him. On this evidence, Edward's Scottish campaigns between 1298-1303 were a series of administrative snarl-ups, defined by crippling expense, bumbling ineptitude and multiple betrayals. Not that his Scottish enemies were always pulling up trees either. In 1301, their combined field army in the south-west failed to take a single castle. The English, meanwhile, apparently couldn't march five steps without going bankrupt. Their futile conflict wheezed and spluttered to a halt in September, mainly because both sides had run out of ideas.

Both sides suffered from variable leadership. Edward himself, while no Alexander, was no Redvers Buller either (a particularly useless British Boer War general). He was, at any rate, a more formidable prospect than the men under him, such as Earl Warenne and the Earl of Lincoln. In Warenne's defence, he was old and ill, and would have preferred a stint in Hell to Scotland. Edward's most able captain was a former seneschal of Gascony, John de St John. The king moved heaven and earth to get St John out of a French prison and into Galloway, where English fortunes notably improved under his stewardship.

The roll-call of Scottish commanders, away from the flagship figures of Wallace and Bruce, doesn't exactly gleam with talent either. Step forward the Earl of Buchan, whose attempt to ambush Edward at the River Cree ended with his entire army high-tailing it across the glens. Then we have Sir Herbert Morham, who abandoned his men at Stirling so he could ride off in pursuit of Joan de Clare, widow of the Earl of Fife. He later got himself captured and thrown into Edinburgh prison, which placed his father in an interesting position: Morham senior was serving in the English garrison of Edinburgh castle. Quick, a statue to the Morham boys! Let it be fifty feet high, I say, and garlanded with blazing saltires. The best of them all was Sir John Comyn of Badenoch, a remarkable figure, victor of the battle of Roslin and consistent defender of Scottish liberty. That is, until Bruce stuck a knife in him.

In spite of all his problems, and the pressures elsewhere, Edward kept pounding away. The main battleground in these years was the south-west, which could be described as a state of civil war. Galloway was not yet fully absorbed into the kingdom of Scotland, something Edward appreciated. A number of the local dynasties supported the English and continued to do so for many years, long after it became clear the war was lost (or won, depending on one's point of view). Edward attempted to exploit these divisions by digging out Thomas of Galloway, who had spent fifty years in a Scottish prison, and packing the bewildered old coot off home, armed with a charter of liberties. Here Watson might have included a comparison with Wales: after 1297, Edward sought to gain the support of the Welsh by doling out charters of liberties to local communities. The policy was effective, which might have influenced Edward's attempt to repeat it in Scotland.

This leads onto the (in my opinion) best section of the book, which deals with the crux year of 1302. Up until this point, despite the defeat at Falkirk, the Guardians had been doing rather well. Despite repeated invasions, Edward could not claim to have control of Scotland beyond the south-east, and a toe-hold in Galloway. The Scots were also holding their own on the diplomatic front. A vital factor was the threat of the return of John Balliol, backed by a French army.

1302 marked the turn of the tide. First, Robert de Bruce – later Robert I – defected to the English camp. Then King Philip chose to renege on the Treaty of Asnieres, whereby he was supposed to take custody of much of south-west Scotland. The deadline for this transfer was 16th February, which came and went without a Frenchman in sight. Edward, who had shrewdly guessed that Philip would ditch his Scottish allies, carried on stocking his garrisons. Watson describes all this, without speculating as to why Philip broke his own agreement. The answer may lie in the final peace between England and France, whereby Edward once again became Philip's vassal. That in turn meant Philip could summon Edward to do military service in Flanders. He did just that, and the term of service just happened to coincide with the broken treaty. Not for the last time, a French king had used the Scots as useful collateral.

The real shock came at Courtrai in July, where the French army crashed to a stunning defeat at the hands of Flemish citizen-militia. Faced with his very own Stirling Bridge, Philip was obliged to hurl all his resources at Flanders. This meant reaching an agreement with Edward, which in turn meant the restoration of Gascony to the English. After the final treaty was agreed at Paris in early 1303, Edward was free – at last – to deal with Scotland.

That final push, as Watson describes it, was nothing short of monumental. After years of grinding warfare and high taxes, Edward somehow galvanised his stuttering war-machine for one last tilt at the Scots. Even Watson, with her detailed knowledge of the nuts and bolts, admits defeat here. Edward's last charge into Scotland, given the tattered state of his finances, was, on the face of it, impossible. Yet somehow he got the thing done, and Watson admits to a certain baffled admiration. One does not have to 'like' this particular Plantagenet to acknowledge his strengths. Among these, to judge from Watson's narrative, was an almost sublime ability to bulldoze through any problem.

The last third of the book is taken up by the Strathord agreement of 1304, and Edward's subsequent Ordinance for the government of Scotland. At Strathord, the Guardians finally agreed to surrender. This was far from unconditional, however, and in return Edward had to agree to a complex set of terms. Watson is cautious here. In terms of the military situation, Edward had succeeded in crossing the Forth, for the first time since 1296, and driven a wedge between the Guardians and their eastern sea-ports. Their only hope now lay in French support – fat chance, even though Philip kept making noises – or defeating Edward in a pitched battle. Nobody, Edward included, wanted to roll that particular die.

At the same time, while Edward had clawed back the initiative, he only had a limited window to exploit it. His coffers really were bare, now, and he could only pay for the war by deferring on loans and relying on tithes extracted from the papacy. How long he could have maintained his army in Scotland is a moot point, but in any case the Guardians went for settlement.

Whatever his flaws, Edward was not stupid. He had learned his lessons: in contrast to 1296, the king and his advisers spent eighteen months carefully drawing up the new ordinance for Scotland, in consultation with Scottish magnates and clergy. From the English perspective, this was intended to be a permanent settlement. As for the Scots, we should not make assumptions based on that dratted hindsight. At the very least, their renewed oaths of allegiance to Edward were meant to hold good for as long as he lived. After he died – and everyone could see that Edward was on his last legs – the oaths would have to be re-sworn to his successor. That, whatever one makes of Edward II, was an entirely different kettle of fish.

Watson also discusses the moral aspect, as the Guardians would have understood it. Up until 1303, they had been fighting for the restoration of their king, John Balliol. When it became clear Balliol was not going to return, that meant there was no king to fight for. This presented a dilemma. It may seem strange to us, but in the fourteenth century the state was very much linked to the individual. Put simply: no king = no state = no motive. The notion of the homeland as a thing worth fighting for in itself was not yet crystallised. At least, not to everyone who mattered.

Equally, we should not lavish too much praise on the brilliant foresight of the Guardians of Scotland. Whatever concessions he made, Edward had (temporarily) won the main point. Here, Watson quotes Bruce's biographer, the late GWS Barrow:

'There was no escaping the fact that Scotland was once more what she had been in 1296, a conquered country, occupied by foreign garrisons and governed by the foreign officials of a foreign king'.

And there Watson leaves it, pretty much. Neither Edward nor his banged-together empire would last much longer. The Scots soon found a new leader in Robert de Bruce – a curious case of gamekeeper-turned-poacher – and the war started up all over again. Edward's fate was to die in a barren Cumbrian outpost, within sight but not within reach of Scotland. Bruce's road to Bannockburn is pretty well-worn, and goes beyond Watson (and Edward's) remit.

As my somewhat windy review has hopefully demonstrated, this is not an easy subject. Partisan arguments will rage forever, probably, even after this sceptic isle has sunk beneath the waves. Pleas for calm are probably futile, but it may be worth quoting the author's final statement:

“War is, and no doubt always will be, expensive, tedious, horrifying, but, above all, complex”.

Published on March 14, 2022 05:20

March 9, 2022

Careful what you wish for

Attached is a picture of the statue of Jan Breydel and Peter de Coninck in Bruges, Belgium. Who they? You may well ask.

Attached is a picture of the statue of Jan Breydel and Peter de Coninck in Bruges, Belgium. Who they? You may well ask.I've recently been taking a closer look at events in Flanders leading up to the battle of Courtrai in July 1302. Breydel and Coninck are regarded as national heroes who led the 'Matins of Bruges', a revolt against French occupying forces that eventually led to Courtrai, an astonishing battle in which the French feudal host was smashed by an army of Flemish citizen militia.

According to legend, Jan Breydel was one of the leaders of the Flemish resistance – a Flemish version of William Wallace, perhaps.

However, in recent times serious doubt has been cast on Breydel's role in the uprising, and even his identity. Lisa Demets, a young historian at Ghent, has searched through the existing public records and uncovered some very disturbing evidence.

There were in fact three men named Jan Breydel active at this time; they came from a family of local butchers in Bruges, employed to supply meat to the Flemish army. None of them played a leading role in the Bruges Matins or the battle at Courtrai. The only one who made any impression on the record was a town drunk accused of homicide.

The legend of Jan Breydel was apparently invented by the family about a hundred years later. This was an attempt by the Breydels to increase their political influence and status in Bruges. According to Demets, this kind of bogus rewriting of family history was quite common.

Which is all most unfortunate. Apart from the statue, Breydel also has a football stadium named after him. Yet the entire legend is, allegedly, based on a pack of politically motivated falsehoods.

We have our own home-grown versions, of course. I am not for a moment suggesting that the real William Wallace was a drunken tradesman, but his legend was undeniably spun by later generations of poets and chroniclers, notably Blind Harry. The historical Wallace was at least a recognisable individual, who did (briefly) lead an effective revolt against the English.

English folk heroes also have feet of clay. The real Dick Turpin (yes I know, out of period) was an unpleasant horse thief and woman-beater. As for Robin Hood, the most likely historical inspiration is one Robert of Wetherby, an 'outlaw and evildoer' hunted down and hanged in chains at York in 1225. Far from a benevolent hero, Robert was evidently considered a serious threat to the peace, and in all likelihood a nasty dangerous brute.

I guess the theme here is be careful what you wish for. Humans are so very good at spinning myths, and then choosing to believe them. Odd species, very.

Published on March 09, 2022 05:01

March 8, 2022

Cooking the books

'We observed the feast of Easter with due solemnity in Chester and, as the result of the Archbishop's sermons, many people took the Cross. Then we set out for Whitchurch and Oswestry. As we entered their territory, we were met by the princes of Powys, Gruffudd ap Madog, Elise and others, with a number of their local supporters'.

'We observed the feast of Easter with due solemnity in Chester and, as the result of the Archbishop's sermons, many people took the Cross. Then we set out for Whitchurch and Oswestry. As we entered their territory, we were met by the princes of Powys, Gruffudd ap Madog, Elise and others, with a number of their local supporters'.Gerald of Wales, in Book II Chapter of his Journey through Wales, describes his meeting with the rulers of Powys in 1188.

Gruffudd and Elise were two sons of King Madog of Powys, murdered at Whittingdon by the rulers of Gwynedd in 1170. Gruffudd is a shadowy figure: no charters or poems addressed to him have survived, but after his death in 1190 the Brut hailed him as:

'...ye haelaf o holl tywyssogyon Kymry'

(...the most generous of all the rulers of Wales)

Elise appears to have been subordinate to his brother. However, after Gruffudd's death Elise came into his own. One of his charters, issued in 1191, records a grant of pasture of the whole province of Penllyn:

'...in the second year after the death of my brother Gruffudd, when I first possessed the aforesaid province'.

Elise secured his grip by acting as a major donor to the abbey of Strata Marcella, and forging a political alliance with Gwenwynwyn of southern Powys.

It seems he was not above fiddling the paperwork. Two of his charters to Strata Marcella are dated 18 April 1183 and 15 May 1198. Despite being separated by 15 years, they have exactly the same names on the witness-lists, in the same order. The figure who appears at the head of both lists is Gruffudd, abbot of Strata Marcella.

However, the abbot of Strata Marcella until 1187 is recorded as Ithel, not Gruffudd. Although Ithel was succeeded by Gruffudd, the latter died in 1196. Therefore Gruffudd cannot have witnessed either charter,

Further, internal evidence suggests the charters were drawn up at the same time by an individual scribe, called 'Hand A' or 'Scribe A' by historians. Both documents include the sign of the 'papal knot' as a mark of suspension i.e. a symbol written over a letter which allowed shorthand of a particular term.

Why were the charters forged? They probably date from after 1202, when Llywelyn the Great and Madog ap Gruffudd had displaced Elise inside Penllyn and Edeirnion. In the light of these threats to their patron, the monks of Strata Marcella forged the documents to 'prove' their rights to local estates.

There was nothing unusual about this kind of tampering, of course: one encounters it time and again in the medieval era, from the Great Cause in Scotland to disputes over Gascony to Anglo-Saxon charters – etcetera etcetera. Everyone was guilty.

Published on March 08, 2022 02:17

March 7, 2022

The fires of Saint Chad

In early March 1264, the Feast of St Chad, Dafydd ap Gruffudd led an army of Cheshire and Shropshire men into Staffordshire. His co-commanders were William de la Zouche, justiciar of Chester, and Hamo Lestrange (an ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, as it goes).

In early March 1264, the Feast of St Chad, Dafydd ap Gruffudd led an army of Cheshire and Shropshire men into Staffordshire. His co-commanders were William de la Zouche, justiciar of Chester, and Hamo Lestrange (an ancestor of Owain Glyn Dwr, as it goes).Dafydd's purpose was to attack the lands of Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, to distract him from joining the army of Henry de Montfort, who was besieging the royalist-held town and castle of Gloucester. Dafydd's ally, Lord Edward, was marching up from the west to try and raise the siege.

If Ferrers was able to bring his power south and link up with the Montfortian host, Edward and Dafydd would be screwed. Hence, the aim of the game was to keep them divided.

Dafydd's men stormed the town of Stafford and apparently impregnable castle of Chartley, which had recently been refortified. Then they doubled back and burnt the town of Stone, also taking time to burn and plunder all the local churches. This merriment lasted ten days. On 12 March they attacked Stafford again, only to be repulsed by a scratch force of barons, presumably rushed into action by Ferrers or Henry. Dafydd then withdrew to the border, trashing Eccleshall on the way and breaking more churches.

The raid served its purpose. While Dafydd burnt and pillaged, Edward got his men over the Severn in some commandeered boats, and into the castle. Ferrers arrived too late to prevent Henry agreeing to a truce. Never a very committed Montfortian, Ferrers got distracted at Worcester, where he razed the town and obliterated the Jewish quarter (or, in modern parlance, 'liberated' it...)

When Ferrers learnt of the truce, he blew his top:

“The earl Robert de Ferrers, when he came thither, he was well-nigh mad for wrath that they had made agreement. He smote his steed with his spur, as did all his company. And turned himself for wrath again, as quick as he might hasten.”

The disgruntled earl turned about and rode north, leaving Henry looking very silly indeed. Ferrers and Dafydd would later become brothers-in-law. And so it went on.

Published on March 07, 2022 07:23

March 6, 2022

Combined arms

The chronicler Henry of Huntingdon describes Welsh soldiers at the battle of Lincoln in 1141.

The chronicler Henry of Huntingdon describes Welsh soldiers at the battle of Lincoln in 1141.First he puts a speech into the mouth of Baldwin Fitz-Gilbert, one of King Stephen's knights:

'You may despise the Welsh he has brought with him, as ill armed and recklessly rash; and being unskilled and unpractised in the art of war, they are ready to fall like wild beasts into the toils'.

When the battle starts, the Welsh are placed on the flanks of Earl Robert of Gloucester's army. This does not end well:

'The division commanded by the Earl of Albemarle and William of Ypres charged the Welsh as they advanced on the flank, and completely routed them'.

The Welsh at this time seem to have been light infantry, knife and javelin-men. Expert guerilla fighters on their own turf, but vulnerable if lined up on an open field against armoured knights. A similar disaster befell them at Evesham in 1265, where Simon de Montfort's Welsh levies broke in the face of a cavalry charge.

In the following decades the Welsh seem to have adapted. Accounts of the battle of Maes Moydog in 1295 describe Prince Madog forming his men into a phalanx of long spears, which repels the first English cavalry charge. Two years later, in Flanders, the French apparently refused to attack Edward I's Welsh archers in the open.

This seems odd – unless they had changed their gear and tactics, the Welsh should have been mowed down as they were at Lincoln and Evesham. Possibly they were using 'combined arms' by this point. A few decades later, during Edward III's Flanders campaign, an English soldier described in a letter how the Welsh formed up into phalanxes of long spears on the battlefield, with archers on the flanks.

Published on March 06, 2022 06:46