David Pilling's Blog, page 4

April 8, 2023

Banners of the King (2)

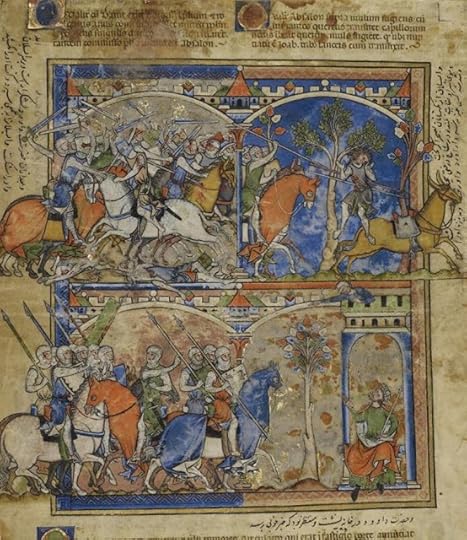

Northampton was defended by Simon de Montfort junior and about a hundred knights. Many were men of the second rank, of no great power or reputation: William de Wheltoun, William de Warre, Robert Maloree, Eustach de Watteford, etc. Who they, you may ask? You may well.

Northampton was defended by Simon de Montfort junior and about a hundred knights. Many were men of the second rank, of no great power or reputation: William de Wheltoun, William de Warre, Robert Maloree, Eustach de Watteford, etc. Who they, you may ask? You may well. Simon did have a few important knights with him. These were Peter de Montfort (no relation), a tough veteran of the Welsh March; Baldwin Wake, a baron of Lincolnshire and (alleged) descendent of Hereward, the famous English folk hero; William Ferrers, younger brother of Robert, the notorious sixth earl of Derby. Otherwise the garrison was reinforced by a group of Montfortian students from Oxford, driven from the town and university by the king. These young men fought against Henry 'with the utmost zeal, armed with bows, slings and crossbows', and even brought their own home-made banner to drape over the town gates.

To boost numbers, the Montfortians tried to conscript local men of the shire. These were summoned to assemble at Cow Meadow, outside the town. One of Simon's followers, Walter Hyldeburn, subjected them to a fierce speech on the justice of the rebel cause and the bad faith of the king. After this call to arms, every man was forced to join the army and prepare for battle. No excuses.

One of the reluctant conscripts, Stephen de la Haye, had only come to Northampton to collect rent money. He had absolutely no desire to fight anyone, and escaped by swimming his horse over the river.

Attached is a pic of medieval students, which I suspect some wag may have doctored.

Published on April 08, 2023 06:03

Banners of the king (1)

In early April 1264 Henry III declared war on Simon de Montfort. He raised the dragon standard, a specially made war banner with jewelled eyes and a tongue 'seeming to flicker in and out as the breeze caught the banner, and its eyes of sapphire and other gems flashing in the light'.

The king targeted Northampton, held against him by Simon junior. Along with London and the Cinque Ports (the coastal towns in Kent and Sussex that commanded access to the Channel), Northampton was one of three main rebel strongholds. From his base at Oxford, Henry could not march on London or the ports without risking a flank attack from Northampton. The town also cut off his communications to the north and west.

Henry's army was formidable. He had many of the chief magnates of England, including Lord Edward, Richard of Cornwall, William de Valence, Philip Basset and Hugh Bigod, as well as other great men. The king also enlisted the loyal barons of the Welsh March; Roger Mortimer, James Audley, William de la Zouche, John Vaux and John Grey, among others.

One notable exception was Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, who had thrown in his lot with the rebels. His defection was a major blow to the king, since the great Honour of Clare comprised vast estates in the southern Marches and lordship of Tonbridge in Kent. This deprived Henry of territory, wealth and manpower.

Published on April 08, 2023 04:37

April 4, 2023

King vs Church

April 1297 witnessed the culmination of a remarkable dispute between the king and the church. On 2 April Edward I ordered the Exchequer to sell the goods that had been seized from the clergy; this would not only raise money, but put pressure on those churchmen who had not yet come to terms.

The king needed money quickly: on 11 April he declared it did not matter if the goods were sold for less than market value, so long as they were sold. Those clergy who had not paid their fines 'had failed their liege lord, and their own nation, and the realm'.

The source of this dispute was the war with France. Edward was in dire need of cash to send troops and supplies to his hard-pressed garrisons in Gascony, and raise an army to join his allies in Flanders. A military summons at the Northampton parliament in February ended in disaster, when his magnates simply refused to fight overseas. Edward was forced to take the risk of recruiting men in Wales, which had been in revolt only two years earlier. Fortunately for him, the gamble paid off.

It proved much more difficult to squeeze money out of the church. Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury, led the opposition. He argued that the Pope had forbidden the clergy from paying tax to the lay power; only if the danger to the kingdom was very great, would the church agree to pay up.

Edward's argument was straightforward. The realm was in danger, and everyone must contribute to defence. Anyone who refused was no longer entitled to the king's protection. Why should he protect those who failed in their duty?

Winchelsey's stance was undermined by the northern clergy, who paid up without complaint. When their southern brethren held out, Edward simply outlawed them, en masse, and ordered the seizure of all lay fees belonging to the clergy of southern England. The king then made it known that his protection could be bought for a sum equal to the proposed tax. Predictably, individual clergymen came flocking to buy their pardons.

Winchelsey was placed under extreme pressure. Royal officials moved in to lock and seal many of the buildings of Canterbury cathedral priory. By 6 March the grain stored in them was rotting and overheated for lack of care. The archbishop decided to confront the king in person and went to meet Edward at Salisbury.

Their talk was futile. Edward argued that even if the Pope himself held lands in England, he would be entitled to take them into hands for the defence of the realm. Winchelsey suggested they ask the Pope to advise if England was in sufficient danger to justify taxing the clergy. Unsurprisingly, Edward stonewalled that idea. No chance, Your Grace. The only concession he made was to allow those clergy who had bought protection to sow their lands with seed.

This was all very reminiscent of the Henry II-Becket dispute; what it boiled down to was the rights of the crown versus the rights of the church. The rights and wrongs of the dispute are a moot point. Typically, Edward took extreme action in the face of a crisis. In his defence, England was at war and under genuine threat of French invasion.

In the end, Winchelsey failed for lack of support. He summoned a church council, where his own clergy argued that the grant of taxation was necessary. Whether they really believed this, or didn't fancy being outlawed and stripped of cash and assets, is another moot point.

In the end, Winchelsey gave up and proposed that every man should follow his conscience. He and his clergy departed from the council, as a chronicler noted, "like wandering sheep without a shepherd". They continued to buy their peace with the king. By September 1297 the sum of £23, 174 had been paid into the exchequer, almost exactly the same amount as the original tax demand.

Winchelsey did not go the same way as Becket. Shortly before the king left for Flanders, he appeared on a raised wooden platform with Edward, before a packed crowd outside Westminster. There, to cheers from the plebs, they embraced and wept and exchanged the kiss of peace. And whispered a few choice words to each other, no doubt.

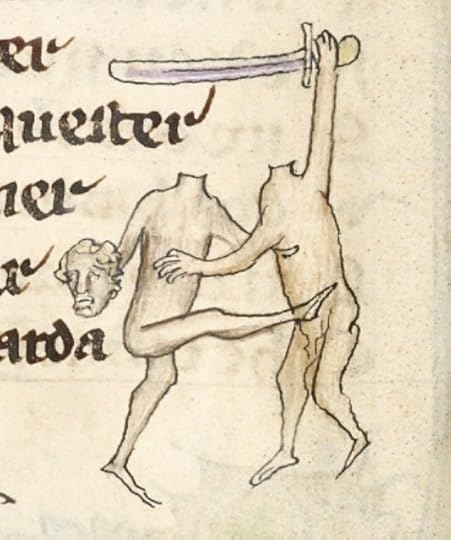

Attached, for lack of suitable images of Edward and Winchelsey yelling at each other, is a pic of the fate of Saint Tom.

Published on April 04, 2023 03:47

March 5, 2023

Sharing beds

The financial accounts of Robert Burnell, de facto regent of England from 1270-1274, survive almost in their entirety. These are revealing, and show the problems and difficulties experienced by a land without a king.

For instance, the turbulent state of the Welsh March is shown by a payment of £100 to the constable of Montgomery Castle, at a time when the borderlands were sliding into outright chaos (again). Burnell also paid out £270 for a large quantity of grain sent to Gascony when there were fears of a French invasion - 'quando timebatur de adventu Regis Francie ad partas illas cum exercitu'.

Another 200 marks went to Thomas de Clare, younger brother of Gilbert de Clare and Edward I's bedmate, sent to Gascony when rumours of French invasion were still circulating. Burnell then paid 250 marks for the expenses of John de le Lynde, sent to the French court in Paris and then Rome, presumably to try and calm things down.

Thomas de Clare had the same relationship with Edward as Richard I and Philip Augustus. In this era, to share a bed with another man was a sign of royal trust and favour, nothing more. That said, if anyone wishes to redefine Longshanks as a gay icon, please, have at it. Just let me get the popcorn.

Published on March 05, 2023 03:20

March 3, 2023

Between 1270-74 England was engulfed by a rising tide of ...

Between 1270-74 England was engulfed by a rising tide of lawlessness. This was triggered by Lord Edward's absence on crusade, the lingering resentments of the Montfortian wars, and the incapacity of central government.

One of those entrusted with guarding the kingdom was Edward's uncle Richard, Earl of Cornwall. Richard was competent and immensely rich, able to bring the authority of his royal status, wealth and prestige. In October 1270, for instance, he appointed a new sheriff of Lincolnshire and granted the castle and county of Carlisle to the bishop of that diocese. A few months later, March 1271, Richard took charge of suppressing a mysterious rebellion in Yorkshire; he gave orders for the arrest of 'all persons making congregations, conventicles and conspiracies against the peace' in that county. This was just one of the 'wars and rumours of wars' that were erupting all over England.

Then, a piece of appalling news reached London. Richard's son, Henry of Almaine, had been murdered at the church of Viterbo in Italy. While attending Mass at the Chiesa di San Silvestro, he was attacked by Simon de Montfort junior and his brother Guy. When Henry clung to the altar, begging for mercy, they cut his fingers off and dragged him outside. There, in full public view, they cut out his eyes and testicles and finally hacked off his head.

This, Simon declared, was in revenge for the bloody death of his father at Evesham in 1265. Since Henry was not even present at Evesham, let alone culpable, Simon's defence was preposterous. In any case, blasphemy and homicide were just that, regardless of motive.

The murder had a destabilising effect on England, as it was supposed to. Richard never recovered from his son's death: in December 1271 he suffered a near-fatal stroke that left him paralysed down one side and unable to speak. After lingering for a few months, he died at Berkhampstead on 2 April 1272. Meanwhile England slid further into chaos.

Published on March 03, 2023 06:59

February 22, 2023

A Shropshire Lad (1)

Robert Burnell, lord chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, was born at Acton Burnell in Shropshire, six miles SE of Shrewsbury, in about 1240. Otherwise we know little about his early life, except that he was one of four brothers. It is not known who his parents were or his precise date of birth.

Robert Burnell, lord chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, was born at Acton Burnell in Shropshire, six miles SE of Shrewsbury, in about 1240. Otherwise we know little about his early life, except that he was one of four brothers. It is not known who his parents were or his precise date of birth. Nothing is known of Burnell's upbringing or education, before his sudden appearance as a royal clerk in the 1250s. The monks of Buildwas Abbey, sometime in the fourteenth century, concocted a pedigree for Burnell tracing his family all the way back to a Robert Burnell who (allegedly) came to England with the Conqueror.

The pedigree was an invention: "...a tribute devised by obsequious monks to gratify the pride of the Burnells in the days of their prosperity" (Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire).

This sort of fabricated genealogy was quite common. For instance the powerful Clanvoe family, descended of the lineage of Hywel ap Meurig, forged a descent from the old lords of Deheubarth. The family was in fact descended from an obscure Welsh tenant of the Mortimers in the Middle March.

(The pic is of Acton Burnell castle near Shrewsbury)

Published on February 22, 2023 05:20

February 20, 2023

The battle of Roslin

February 1303 witnessed the battle of Roslin, in which the Scots under John Comyn of Badenoch and Simon Fraser defeated an English force led by John Segrave.

In the pantheon of Scottish victories, Roslin seems to rank well below the likes of Stirling Bridge and Bannockburn. This is, perhaps, due to Comyn being generally perceived as a traitor who richly deserved a dagger in the guts, delivered by Robert de Bruce at Dumfries church in 1306. I have argued before that Comyn is much maligned, a victim of Bruce propaganda, but to little avail. Some impressions just stick and there is little point wasting energy on such things. Not my problem, squire.

Edward I had placed Segrave in command of an expeditionary force, ordered to reconnoitre Scotland before the main English invasion in the autumn. The size of his force reached a peak of 119 men-at-arms and 2067 footsoldiers by January 1303, probably reduced by the time of the battle in February. Segrave was dispatched, specifically, to repel the Scots threatening the English garrison at Roxburgh.

According to Walter of Guisborough, Segrave divided his men into three divisions or troops, distanced from each by about two leagues. He was then led into an ambush by a certain 'boy', who was really on Comyn's side. A notable feature of these Scottish wars is the frequent use of women and boys as spies. I like to think it was the same boy throughout, cheerfully playing off both sides and making a hatful of cash into the bargain.

On 24 February the first English troop, about three hundred men under Segrave's personal command, was attacked and scattered. The recorded casualties are light (just five horses), but Segrave himself was captured. Guisborough claims the second troop came up and rescued him, but this cannot be correct: a couple of weeks later, Edward I paid a ransom for Segrave, implying he was in Scottish custody.

One of the English casualties was Ralph Manton, the king's treasurer, also called Ralf the Cofferer. He was taken prisoner by Simon Fraser, who accused him of embezzling funds when Fraser had been in Edward I's service. After this angry speech - slightly embarrassing, in context - Fraser ordered one of his servants to cut off Ralf's hands and leave him to bleed to death in the forest.

Roslin was later blown out of proportion by the 15th century Scottish chronicler, Walter Bower, who claimed the English lost upward of 80,000 men. This sort of wild boasting and exaggeration was common: for instance, the English claimed that Wallace lost a hundred thousand men at Falkirk. Such losses would have wiped out the entire adult male population of the British Isles, never mind Scotland.

Nevertheless, Roslin was a significant morale-boosting victory for the Scots at a bleak time. It made no real difference to Edward's plans (although one imagines the royal eyes rolling a little at the news). The battle may, however, have persuaded him that Comyn and his allies were still capable of serious resistance. The terms of the negotiated settlement of Strathord, almost a year later, would imply as much.

Published on February 20, 2023 05:15

February 17, 2023

Walking free

In February 1272 Roger Godberd, the notorious bandit chief, was hunted down and captured by Reynold Grey, High Sheriff of Nottingham. He was held in various prisons for four years and finally stood trial at Newgate in April 1276.

In February 1272 Roger Godberd, the notorious bandit chief, was hunted down and captured by Reynold Grey, High Sheriff of Nottingham. He was held in various prisons for four years and finally stood trial at Newgate in April 1276. At his trial, Godberd produced charters of Henry III, which pardoned him of all offences. However, these documents only applied to his first period of outlawry before October 1266, and the Dictum of Kenilworth. They did not cover his second term as an outlaw between 1269-72. Hence, he should have been executed. His lieutenant, Walter Devyas, was beheaded in 1272, and by rights Godberd should have gone the same way.

Instead, astonishingly, he walked free. Godberd was still alive and kicking in 1287, when he was briefly imprisoned again for poaching in Sherwood Forest. Ironically, one of his fellow poachers was Reynold Grey, the former sheriff. They and several others were bailed by one Henry le Lou.

There is no reason to suppose that Godberd died anywhere except in his bed, probably in the 1290s. His son, Roger junior, was allowed to inherit the tenancy of Swannington manor, now in the possession of Edmund of Lancaster. The king, Edward I, had an interesting relationship with these outlaws. Back in 1269, before going on crusade, he had arranged a pardon for Godberd's ill-fated lieutenant, Walter Devyas. This proved most unwise, as Devyas immediately resumed a life of violent crime. When he was recaptured, in 1272, there was no mercy.

Godberd can only have owed his unlikely salvation to the king. At the start of his reign, Edward I wished to settle England as soon as possible, and knew that could not be achieved with a round of bloody executions. One of his first parliaments issued a general pardon to all of Simon de Montfort's surviving followers, which probably explains Godberd's survival.

Published on February 17, 2023 03:25

February 14, 2023

Taking heads

The other interesting case at Rhuddlan, heard before the king on 14 February 1283, concerned the death of a man in Ireland. This was a certain O'Donald, whose head had been brought to the Exchequer at Dublin by one Thomas Mandeville.

The other interesting case at Rhuddlan, heard before the king on 14 February 1283, concerned the death of a man in Ireland. This was a certain O'Donald, whose head had been brought to the Exchequer at Dublin by one Thomas Mandeville. The custom of head-taking was a commonplace way of dealing with outlaws - 'wolfsheads' - in Ireland and Wales. In Ireland it was a part of the legal system, and often led to squabbles over money. For instance, in 1282 the Earl Marshal complained that the Justice of Ireland had fined him 100 marks for the beheading of Art Mac Murrough. This was against the local custom, since the head had not yet been 'proclaimed' with the consent of the earl or his freemen.

In the case of 14 February, Edward I ordered that Mandeville should be paid his fee. This was the standard bounty for bringing the heads of outlaws and felons before the local justices. O'Donald's offence is not recorded, sadly. It should be noted that outlaws had no legal rights or protection whatsoever. Anyone could kill them, in any way, without fear of censure. This explains the fate of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales, lured to his death in a way that would have otherwise been seen as dishonourable.

It also explains why Sir William Wallace got no formal trial at Westminster, after his capture in August 1305. Wallace had been outlawed by the Scottish parliament at St Andrews in February, and outlaws were not entitled to a trial. It might be argued that Edward I forced the Scots to condemn Wallace. However, when he threatened to do the same to James the Steward, an important nobleman, the Scottish lords closed ranks and persuaded Edward to change his mind. They did so because the Steward was one of 'them', a member of the elite club. Wallace was not.

Published on February 14, 2023 06:27

Moved by piety

On 14 February 1283 Edward I was at Rhuddlan. The war in Wales was still raging, but the king and his advisers made time for other business.

On 14 February 1283 Edward I was at Rhuddlan. The war in Wales was still raging, but the king and his advisers made time for other business. On this day they dealt with six cases. Edward took a personal interest in the case of Madog de Brompton, a Welshman accused of murdering one Roger Dodesune. The king was shown the verdict of a jury in Shropshire, which found that Madog had killed Roger in self-defence. Edward, 'moved by piety', agreed with the verdict and ordered Madog to be pardoned and restored to his lands, goods and chattels.

It would be nice to know more about this Madog. Brompton (Brontyn in Welsh) is a hamlet in Shropshire, right on the border: it lies between Church Stoke and Newtown, both in Powys. Perhaps Madog was related to one of the local mixed-'race' families. The Antiquities of Shropshire record that Great Weston/Weston Madoc was held by Robert fitz Madoc in 1224, as a tenant of Thomas Corbet of Caus. After his death Henry III seized the manor, even though Robert had left an heir, Owain. By 1242 the manor was held by one Hywel de Brompton as a serjeant of the king, but after his death it was seized by John Lestrange. Thomas Corbet then managed to reclaim it at law.

The Chirbury Hundred-Roll records that Hywel de Brompton's heir was later in the custody of Lord Edward (later Edward I) and held his land of the prince worth 100 shillings. This was Roger Fitz Hywel, who held the land of Weston. Unfortunately the editor of the Antiquities could find no further trace of Roger Fitz Hywel or the Brompton line.

Published on February 14, 2023 06:22