David Pilling's Blog, page 9

January 30, 2022

Forever August

Another snippet from my upcoming book on Edward I and France, due to be published by Amberley (date TBC).

Another snippet from my upcoming book on Edward I and France, due to be published by Amberley (date TBC).Below is part of a letter from Adolf of Nassau, King of Germany and titular Holy Roman Emperor, to Edward, dated 24 January 1295:

“Adolf, by the grace of God king of the Romans, forever august, offers greeting and the continuing increase of our alliance and friendship to his most dear friend, the renowned lord Edward, august king of England.

Since an account of our good fortune may please you well, see now how we may bring joy to you, because, in entire fulfilment of our vows, and by the strength of the victorious army which we recently created, with the Lord of Hosts our helper, we have added the provinces of Thuringia, Osterland and Meissen to our dominion and empire; the prince-electors, barons, nobles, citizens and commoners have come under our command, and, both in those lands and also in Saxony, we have ourself caused a general peace to be sworn. Now, however, with all things favourably concluded, we have returned rejoicing to the Rhineland'.

Adolf was referring to his recent military campaign inside the empire, whereby he conquered Thuringia and other German provinces and added them to his power base. Adolf had only been elected Emperor because he was poor, which meant the Electors could treat him as a figurehead.

The Electors had miscalculated: Adolf was not content to be a mere puppet, and set about increasing his power in the empire. He did so by accepting an offer of alliance from Edward, who wanted to recruit German support against Philip the Fair of France. The price of Adolf's support was £60,000 in English sterling, an enormous sum, to be paid in three instalments.

Adolf promptly reneged on the deal. This can be demonstrated by the timing of his actions with the payment of the subsidy. He invaded the province of Thuringia in the second half of October 1294. While the campaign was in progress, he received the first two of the English payments. One was paid shortly after 10 October, the second over Christmas. Strangely – or not - Adolf was suddenly in a position to hire allies and mercenaries.

German chroniclers condemned Adolf for his misuse of the English money, which was meant to equip an army to fight the French. Edward himself was not happy, and never paid over the third instalment. It seems incredible that Adolf had the sheer brass neck to write a letter to his English ally, cheerfully reporting on what he had done, but that is what he did.

It did him no good. Adolf's military expansionism within the empire aroused the hatred of his German subjects, and in 1298 he was defeated and chopped up on the battlefield by the forces of the Duke of Austria. According to one French chronicle, he was thrown from his horse by an anonymous Welshman; if true, this man was most likely an agent of King Edward:

'The Plantagenets send their regards'.

Published on January 30, 2022 04:36

Not a single acre of land

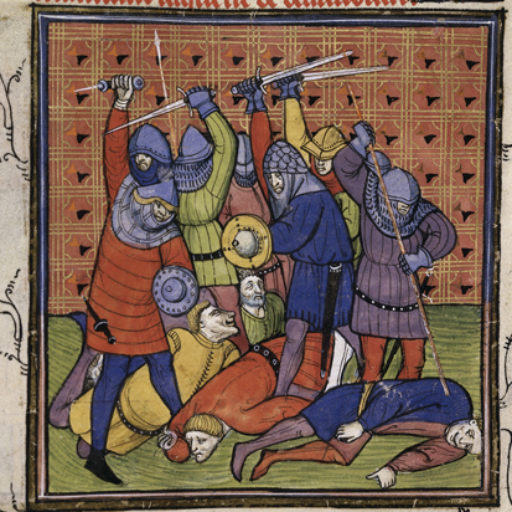

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Llandeilo in 1213. Fought in West Wales, it was a proper set-piece battle, but is almost completely forgotten. Perhaps this is due to it being an internal conflict between the rival princes of Dinefwr, rather than a 'patriotic' struggle against foreign invaders.

Today is the anniversary of the battle of Llandeilo in 1213. Fought in West Wales, it was a proper set-piece battle, but is almost completely forgotten. Perhaps this is due to it being an internal conflict between the rival princes of Dinefwr, rather than a 'patriotic' struggle against foreign invaders. The battle is also an example of the complex dynastic politics of medieval Wales. One army was led by Rhys and Owain ap Gruffudd, sons of King Gruffudd ap Rhys of South Wales and grandsons of William de Braose. They were opposed to their uncle Rhys Gryg – Rhys 'the Hoarse' – who had occupied their ancestral lands inside Ystrad Tywi in south Wales.

Rhys and Owain sought help from King John, who commanded the sheriffs of Hereford and Cardiff to assist them with Norman troops. John ordered his captains to drive Rhys Gryg from Ystrad Tywi, unless he agreed to hand over the castle of Llandovery to his nephews. Rhys Gryg answered defiantly that he would not share with them a single acre of land.

His nephew Rhys, 'full of rage and indignation', led his troops from Brycheiniog into Ystrad Tywi and on 28 January encamped at a place called Trallwng Elgan. On the following day he was joined by his brother, Owain, and the sheriff of Cardiff. The next day the combined host marched to encounter Rhys Gryg in battle.

The Welsh annals give a precise account of the battle. Rhys ap Gruffudd divided his army into three lines or divisions, one behind the other. He was in command of the first troop, the sheriff of Cardiff the second, Owain the third. Once the lines were drawn up, Rhys Gryg launched an attack:

'And Rhys Gryg encountered the first troop. And after they had fought hard, Rhys Gryg was there and then driven to flight, and many of his men had been slain and others had been captured.'

From this it appears the fight was brief, and Rhys Gryg was driven off after a failed assault on the first troop. The victorious allies then pushed on to lay siege to the castle of Dinefwr. After burning the town of Llandeilo Fawr, Rhys Gryg chose to retreat instead of defending the castle. On the following day (31 January) his enemies took Dinefwr by storm:

'And from without archers and crossbowmen were shooting missiles, and sappers digging, and armed knights making unbearable assaults, till they were forced before the afternoon to surrender the tower'.

The defeated Rhys Gryg took his wife and sons and sought refuge at Llandovery with his brother, Maelgwn. However, the great victory of King John and his Welsh allies was only temporary. The defeat of the king's allies at Bouvines the next summer created a power vacuum in Wales, where John was no longer able to intervene. This in turn enabled Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth of Gwynedd – Llywelyn the Great – to seize control.

Published on January 30, 2022 01:29

January 29, 2022

The treachery of his own men

'In that year Rhys ap Maredudd was seized in the woods of Mallaen by the treachery of his own men' - Brut y Tywysogion

'In that year Rhys ap Maredudd was seized in the woods of Mallaen by the treachery of his own men' - Brut y TywysogionThis entry describes events in West Wales in 1291, when Rhys ap Maredudd was captured in the forest of Mallaen by the three sons of Madog ab Aradwr. Rhys, last prince of the House of Dinefwr, had been a hunted fugitive ever since his failed revolt against Edward I in 1287. After being handed over to the king, he was hanged on the common gallows at York.

Madog was one of Rhys's former tenants, and an outstanding example of a Welsh partisan in the royal cause. In May 1277 he acted as surety for Rhys Wyndod, another lord of the west, when the latter borrowed twenty marks from the lord of Kidwelly, Pain Chaworth. Before the end of that year he accounted for five shillings levied upon the Welshry – Welsh community – of the new royal borough at Dinefwr. Madog's most notable service came in 1288, when he served in the royal army sent to recapture Emlyn castle from Rhys ap Maredudd.

His sons continued the tradition of royal service. When Emlyn fell to the king's forces, Rhys was reduced to a hunted outlaw. Rumours swirled that he had fled to Ireland, but by 1291 he was living in the woods of Mallaen. There he was finally brought to bay by three of Madog's sons; Madog Fychan, Treharne Howel, and Rhys Cethryn.

As a reward for this service, the three men received the township of Cil-San, valued at 40 shillings a year, for which they owed suit to the local commote court and a yearly rent of fourpence. Their father had previously held the township, but after his death in 1290 it was taken into the king's hand. Now it was re-granted to his sons, who were also rewarded with local offices: for instance, in 1307 Rhys Goch, a fourth son, received the office of constable in Mallaen by the king's commission.

It seems the betrayal of Rhys ap Maredudd made the lineage of Madog ab Aradwr unpopular. In 1303-4 the local community lodged a petition against the privileges enjoyed by Madog's sons, and paid 10 marks so the latter should have to pay normal rents, just like all other men of the commote.

The family held onto their lands until 1339, when they were obliged to sell all they had – lands, mills, rents etc – to Sir Rhys ap Gruffudd, one of the most prominent figures of 14th century Wales. Rhys was a leading member of the Wyrion Eden, the descendents of Ednyfed Fychan, a powerful lineage that practically ran Wales after the downfall of the Welsh princes. Over a long career, he achieved fame and wealth through loyal service to the Plantagenet kings, and distinguished himself in the French wars. Thus, one family of crown loyalists in Wales was devoured by an even greater lineage.

Published on January 29, 2022 05:48

January 28, 2022

Greed, lack of moral conscience, & brutality

Arnaud Caillau was one of the most important figures in the ducal administration of Gascony during the reigns of Edward I (1272-1307) and Edward II (1307-27). A violent, even brutal, character, he made himself indispensable to the Plantagenet regime during a turbulent period of warfare and political instability.

Arnaud Caillau was one of the most important figures in the ducal administration of Gascony during the reigns of Edward I (1272-1307) and Edward II (1307-27). A violent, even brutal, character, he made himself indispensable to the Plantagenet regime during a turbulent period of warfare and political instability.The chief city of Gascony was Bordeaux, centre of the profitable wine trade, and Arnaud's family were one of the most well-established local gentry families. His grandfather, who bore the same first name, had briefly served as mayor under Henry III. Our Arnaud first appears as a witness to a document dated 12 July 1294, but then dips from sight for several years.

Arnaud resurfaces in January 1303, as the ringleader of a municipal revolt that drove the French out of Bordeaux after a nine-year occupation. This action marked the end of the Anglo-French war that had rumbled on and off since 1294, when Philip the Fair confiscated the duchy from Edward I. In the wake of the revolt, Edward was quick to re-establish his authority over Bordeaux. This was good news for Arnaud, whom the king confirmed in his appointment as mayor. In March 1307, as an extra mark of royal favour, Edward granted Arnaud all the rights the crown possessed over wines and grains in Bordeaux. This effectively made Arnaud the receiver of trade, which in turn gave him a splendid opportunity to cream off the profits and become a very wealthy man.

The English saw Arnaud as an essential pillar of the Plantagenet regime in Gascony. Arnaud himself appears to have hated the northern French with a passion. He was once accused of tearing out a French lawyer's tongue, and of helping the English seneschal of Gascony to hurl a French envoy from a window. The luckless envoy was forced to walk along a table and then tipped outside, breaking an arm and a leg.

Arnaud's personal loathing of the French was expressed in a memorable quote, when he warned his fellow citizens against appealing to Paris:

“Why do you appeal from us to the French? We will kill you, and the king of France has so many things to do with the Flemings that he will not help you, and if a war begins and you are appellants, the English king will conquer Normandy and you will gain nothing unless you give up your appeal”.

However, Arnaud could also be a serious hindrance. Under his leadership, the Caillau faction sided with the Colom, a pro-English faction inside Bordeaux. The Colom were opposed to the pro-French Soler, and the endless gang warfare and street violence was a serious threat to the maintenance of order. In 1310 the jurors of Bordeaux wrote to Edward II, warning him that Bordeaux was sliding into utter chaos, thanks to the 'great damage' committed by Arnaud. As a result he was briefly committed to prison, but the Plantagenet loyalist was too useful to remain in custody for long. Arnaud was soon released, and immediately resumed his career of violence, blackmail and embezzlement.

Despite his sins, Arnaud was eventually appointed lieutenant to the seneschal of Gascony. He used this position to feather his own nest, while at the same time resorting to any means – often illegal – to limit French power inside Gascony. This was all to the good of the fragile English regime, so many of Arnaud's crimes were winked at: for instance, when he was accused of murdering a Frenchman, Pierre Chat, he experienced no difficulty in obtaining a pardon from Edward II.

Arnaud rose higher still. In 1313 he became seneschal of Saintonge, and in 1317 survived a major enquiry into his long list of abuses while in office. At the same time he was accused of treason against the king of France, which probably explains why the English were so quick to exonerate him. Like many Gascons, Arnaud displayed a remarkable talent for playing off both sides for maximum profit. When the French ordered Edward II to banish Arnaud from the duchy, the instruction was simply ignored.

In future years Arnaud acted as a spy against French interests, and continued to receive patronage and reward from the English administration. He enjoyed the special confidence of Edward II, who even protected Arnaud against charges of corruption brought by the king's half-brother, the earl of Kent. The Gascon died in about 1326, still riding high in royal favour, in spite of a career marred by 'greed, lack of moral conscience, and brutality'.

Published on January 28, 2022 05:04

January 27, 2022

Faction feuds

In January 1295 an Anglo-Gascon fleet set out from England to recapture the port town of Bayonne in southern Gascony. The fleet was led by Sir John de St John and Edward I's nephew, John of Brittany.

In January 1295 an Anglo-Gascon fleet set out from England to recapture the port town of Bayonne in southern Gascony. The fleet was led by Sir John de St John and Edward I's nephew, John of Brittany. The situation at Bayonne was complex. Prior to the war it had been a faction-ridden city, similar to the feud between the Colom and Soler at Bordeaux. When the French occupied Gascony the aristocratic party in Bayonne, led by the de Manx family, forged an alliance with the invaders. This forced their rivals, the leaders of the ‘popular’ party made up of shipmasters, craftsmen and mariners, to flee into exile in England. These men, led by Pascale de Viele, had been implicated in the attack on La Rochelle in May 1293. After months of exile, they accompanied St John in his effort to recover Bayonne.

When the Anglo-Gascons approached Bayonne, the citizens immediately rose against their occupiers and shut them up in the castle, ‘for they hated them, because they abused the power which had been wrongly committed to them’. They also had fond memories of St John from his time as seneschal of Gascony. On 1 January 1295 the citizens yielded up the city and told St John not to trouble himself further, since they would take care of the French.

English and Bayonnais ships succeeded in blockading the estuary and captured two large French galleys, which were immediately requisitioned. After holding out for a few days, the French and their partisans surrendered. As at Macau and Bourg, the garrison was permitted to leave unharmed. Most of the leaders of the aristocratic party of Bayonne fled the town, and those who remained suffered loss of property and imprisonment for their support of the French. The ‘popular’ party led by Pascal de Vielle had triumphed, and were soon rewarded by King Edward. Pascal was made mayor, provost and castellan of Bayonne for the duration of the war, and he and others involved in the attack on La Rochelle promised protection from French lawsuits in relation to this.

The re-capture of Bayonne was the single most important English achievement of the war. After the loss of Bordeaux, they now had an alternative capital, and a reserve operational base from which to launch attacks on French-held territory. It was the one major ducal bastion Philip’s armies were never able to threaten again, and so thwarted his ambitions to conquer the entire duchy.

Published on January 27, 2022 02:30

January 26, 2022

Blood and faith!

The paperback version of my latest novel, THE CHAMPION (III): BLOOD AND FAITH, is now available on Amazon!

The paperback version of my latest novel, THE CHAMPION (III): BLOOD AND FAITH, is now available on Amazon! “I am En Pascal of Valencia, the Adalid, the Champion, the Leader of Hosts, and this is my tale...”

1300 AD: the armies of Edward Longshanks and the Guardians of Scotland confront each other. The final battle for control of northern Britain looms. Meanwhile Robert de Bruce, the young lord of Carrick, waits in the background to seize his opportunity. Bruce dreams of taking the Scottish crown for himself, and will stop at nothing to seize it.

En Pascal of Valencia, the poor knight of Aragon, tells the tale of these bloody wars. After surviving the carnage of Göllheim and Falkirk, he now serves the English as warrior, spy and assassin. Pascal stands high in the king's favour, but knows all too well how quickly the wheel can turn...

The CHAMPION (II): BLOOD AND GOLD is a short novella and historical fiction thriller by David Pilling, author of the Leader of Battles series, Caesar's Sword, The White Hawk, Longsword and many more.

Pilling is also the author of two nonfiction works: REBELLION AGAINST HENRY III 1265-1274 and EDWARD I AND WALES 1254-1307, both published by Pen & Sword.

Link to Amazon US: amzn.to/3AAVnUc

Link to Amazon UK: amzn.to/3H5ZnOH

Published on January 26, 2022 04:21

January 25, 2022

Turning points

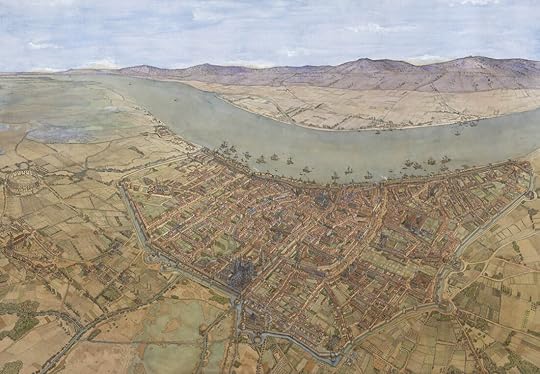

In January 1303, after nine years of occupation, the citizens of Bordeaux rose in arms and drove out the French garrison. The ringleader of the revolt, Arnaud Caillau, was soon afterwards installed as mayor.

In January 1303, after nine years of occupation, the citizens of Bordeaux rose in arms and drove out the French garrison. The ringleader of the revolt, Arnaud Caillau, was soon afterwards installed as mayor.

The context of the revolt was the Anglo-French war that erupted in 1294, when Philip the Fair of France exploited a war at sea between English and Norman pirates to confiscate Edward I's duchy of Gascony. After the failure of peace talks, Edward had no option except to renounce his homage and fealty to Philip and declare war.

Several years of inconclusive warfare followed. Both kings spent oceans of gold constructing grand coalitions against each other: among others, Edward recruited the duke of Brabant, the king of Germany and the counts of Bar and Flanders, while Philip made allies of the Scots, the king of Norway and various rulers of Burgundy and the Low Countries.

All this vast effort and expenditure came to nothing. In autumn 1297 the war fizzled out in a messy stalemate in Flanders, where the rival kings struck a truce instead of risking a battle. The last thing either Philip or Edward wanted was a repeat of the epic battle of Bouvines in 1214, where Philip Augustus had defeated the allies of King John.

The truce meant that Philip was unable to complete his conquest of Gascony, but his troops retained control of the chief city, Bordeaux. Despite several failed uprisings, the French held onto Bordeaux for several more years. Philip was obliged to take hostages from the leading families of the city and send them off to prison at Carcassone and Toulouse. Many died in filthy conditions, which did nothing to improve the popularity of the French regime.

The turning point came in 1302, when Philip's army suffered a shock defeat at the battle of Courtrai in Flanders. The disaster of Courtrai obliged Philip to concentrate all his resources on Flanders. This meant reaching an accommodation with Edward over Gascony. Before negotiations could begin, the people of Bordeaux took matters into their own hands. In January the citizenry rose in arms and forced out the French, who meekly left without a fight. The only violence came from Caillau, who allegedly threw a French lawyer out of a window, after the man had suggested that Bordeaux was rightfully a French possession. To still the lawyer's tongue, Caillau tore it out.

Caillau was installed as mayor by 15th January. The city briefly flirted with republicanism, but Edward I was quick to re-establish his authority. In exchange for confirming Caillau as mayor (and making him receiver of the profitable wine staple)) the English were able to recover Bordeaux. At the same time English and French envoys reached an agreement in Paris, whereby the citizens of Bordeaux were not to be harmed by either side. Edward's hand was strengthened by a little gunboat diplomacy: in February, while talks were still ongoing, he landed an army of almost three thousand Gascon exiles on the coast near Bordeaux. The presence of these men swung the argument in his favour.

Despite repeated French invasions, Bordeaux would remain a loyal Plantagenet outpost until 1453, when the English finally lost control of Gascony. The loss of the duchy was a severe blow to the already fragile administration of Henry VI, and did much to provoke the conflict in England remembered as the Wars of the Roses.

Published on January 25, 2022 04:18

January 20, 2022

Morality tales

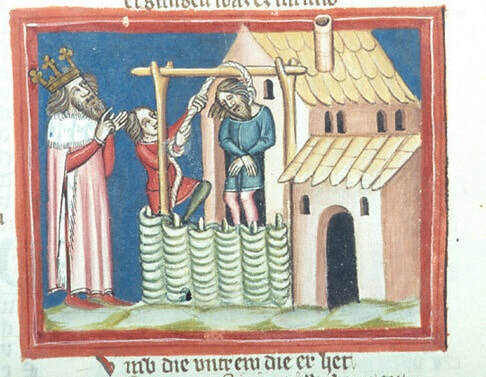

Walter Bower, a Scottish chronicler writing in the mid-15th century, gave this account of the conquest of Wales in 1282:

Walter Bower, a Scottish chronicler writing in the mid-15th century, gave this account of the conquest of Wales in 1282:'At the start of the conquest of Wales Edward Longshanks acquired it through treachery; for when that king of England was hurrying with an army to Wales there was no easy access open for his army into the interior of the country because of the narrowness and all but impassable rigours of the road, until one of the foremost of the magnates and those of noble blood in all Wales, Penvyn by name, was bribed to tell the king to cut with axes certain tracks around a wood and by that route to make a passage for the army, so that thus he might easily be able to follow through his plan for the Welsh. This was done, and as a result of this traitor’s guidance nearly the whole of Wales was ruined, for within a short time Edward the king of England took Wales, part of which has been conquered [already] and the rest of which was now to be brought into order. He fashioned and constructed thirty-seven strongly fortified castles.

Then Penvyn who was a traitor to his own country came very soon to the king to ask for payment of a suitable pension for his opportune advice [as he had been promised]. The king [addressed] him: ‘You have earned a pension, Penvyn. Since therefore it seems just that everyone should receive a reward according to his work, and taking into account your bad record and the reputation of your own name, I rank you as more distinguished than others and will hang you more gloriously because you have proved to be more eminent than all the others of your kindred.’ A very high gallows was therefore erected on which the traitor was hanged, only after he had been paid the immense weight of gold that had been promised him for his villainy and which swung with him at the [appointed] hour as a warning for all traitors and a disgrace to be heeded. And so Wales was subdued until the time of the second King Richard who for greater merit made it over to the Welsh.'

The character of 'Penvyn' was based on a real Welshman named Iorwerth Penwyn. I have mentioned this man before: he was one of the many lesser Welsh landholders or gentry who supported Edward I. Later generations of Welsh poets accused him of selling Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd to the king in exchange for money and land.

The real Iorwerth was not executed, but spent a career in royal service and died in 1317. Bower invented a story about him as a morality tale, meant to warn the Scots of the dangers of Plantagenet aggression and internal conflict, since these things had scuppered the principality of Wales.

Apart from the interesting use of polemic, this extract also shows that Bower was able to draw upon a wide range of sources: apart from the slivers of later poetry, Iorwerth Penwyn was not a well-known character outside Wales. He also drew upon a (lost) tradition of Robin Hood, in which the outlaw was placed firmly among Montfortian outlaws under the year 1266.

Published on January 20, 2022 04:28

January 19, 2022

Bruce and the Loathly Damsel

In early 1302 – exact date unknown – Robert de Bruce submitted to Sir John de St John, Edward I's keeper of Lochmaben. The terms of the submission are described in a petition dated several months later, whereby Bruce came to the king's peace in the presence of St John and 'many good people'. These were presumably his father's knights of Annandale, among others.

In early 1302 – exact date unknown – Robert de Bruce submitted to Sir John de St John, Edward I's keeper of Lochmaben. The terms of the submission are described in a petition dated several months later, whereby Bruce came to the king's peace in the presence of St John and 'many good people'. These were presumably his father's knights of Annandale, among others.The date of Bruce's surrender can possibly be connected to Edward I's decision to stage a 'Round Table' tournament at Falkirk on 20 January, the site of his victory over William Wallace four years earlier. January was an odd time of year to stage such an event; Falkirk had been fought on 22 July 1298, so it was not an anniversary celebration. Edward was in the habit of using these King Arthur-themed bloodsports to make political points. For instance, he staged a Round Table at Nefyn in North Wales in 1284, to symbolise his newfound domination of the principality.

In 1316 a Flemish poet and priest, Lodewijk van Velthem, wrote a detailed account of the Round Table events of Edward I's day. To judge from his account, they were highly ritualised and more than a little bizarre.

The king would announce that a play or 'spel' of King Arthur was to be enacted. He and his best knights would then choose which characters from Arthurian legend to play for the day: van Velthem names Arthur himself, Lancelot, Gawaine, Percival, Agravaine, Bors, Gareth, Lionel, Mordred and Kay.

At sunrise the tourney began. Kay, the buffoon of the legend, was played by some unfortunate who would be set upon by twenty young men. They cut his saddle girths and threw him to the ground, while the audience laughed and cheered. This was all in fun, though, and the knight playing Kay was not (in theory) badly hurt.

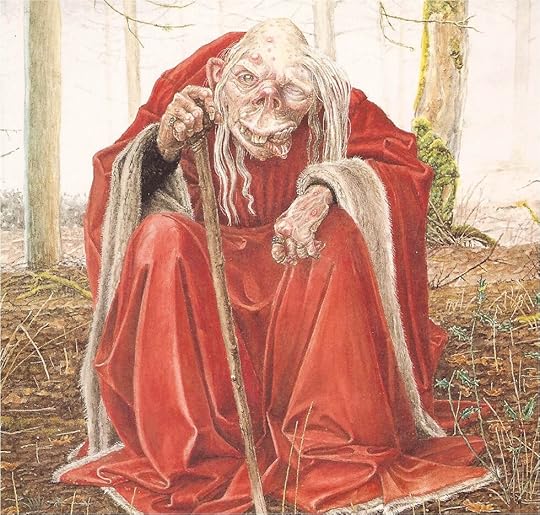

After the tourney was over, the king turned from the field to the banquet hall, where he and his knights sat at the Table Round. After each course of the meal, a squire would enter the hall and abuse the assembled knights as cowards. A challenge would be issued to each knight, who was duty-bound to accept. The squire who entered after the third course, mounted on a thin limping horse, would be dressed up as the Loathly Damsel:

“...her nose a foot long and a palm in width, her ears like those of an ass, coarse braids hanging down to her girdle, a goitre on her long red neck, two teeth projecting a finger's length from her wry mouth..”

All of this may sound a bit unlikely, but similar accounts of Round Table masquerades are given by William of Rishanger, a monk of St Albans, and in French romances such as La Roman de Hem. If he participated, it would be interesting to know which character Bruce chose to play.

Published on January 19, 2022 06:25

January 17, 2022

Sword of Castile

Part of the sword of Sancho IV, King of Castile from 1284-1295.

Part of the sword of Sancho IV, King of Castile from 1284-1295. On 17 January 1284, at Pamplona, a certain Anastre de Montpezat received compensation for horses lost while on campaign in Navarre and Castile. Anastre was a Gascon knight in the service of Edward I and got the money from Hugh de la Vic, 'familiar del rei d'Angleterre'.

The compensation was due from two years earlier, when Anastre was among a troop of Gascon knights and men-at-arms sent over the mountains to help Alfonso X of Castile fight Sancho, his second son. Alfonso wished to leave the crown to his grandsons by his deceased eldest son, Fernando, who had died in a war against the Moorish emirate of Granada. Sancho argued that he was the true heir, due to the old Castilian custom of proximity of blood and agnatic seniority i.e. a principle of inheritance whereby a monarch's children only inherit once the males of the elder generation are exhausted.

When war broke out inside Castile, Alfonso sent a request for military aid to his brother-in-law Edward I. This occurred at the same time as the final war in Wales between Edward and Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Gaston de Béarn, originally summoned to fight in Wales, persuaded the king he would be of more use south of the Pyrenees.

These concurrent wars show the vital importance of Gascony to the English crown. In January 1283 an army of 2400 Gascon knights and mounted and foot crossbowmen was transported over the sea to crush resistance in North Wales; several months later, 6 June, Gaston assembled 41 knights and 59 men-at-arms and their retinues at Bordeaux, and on 13 November led them over the Pyrenees to fight Sancho of Castile.

Published on January 17, 2022 08:39