David Pilling's Blog, page 12

December 9, 2021

Power and control (1)

In 1188 Llywelyn the Great set about establishing his power in Gwynedd. He was confronted by his uncles, King Dafydd ab Owain and Rhodri ab Owain, and two cousins, Gruffudd and Maredudd ap Cynan ab Owain. All of these men were direct heirs of Owain Gwynedd.

In 1188 Llywelyn the Great set about establishing his power in Gwynedd. He was confronted by his uncles, King Dafydd ab Owain and Rhodri ab Owain, and two cousins, Gruffudd and Maredudd ap Cynan ab Owain. All of these men were direct heirs of Owain Gwynedd.Llywelyn's ambition was to crush these rivals and establish a secure practice of succession in the principality. This – in theory – would lead to political stability and an end to the constant internal feuding among rival kinsmen.

To that end he eliminated his opponents by any means. His uncles Dafydd and Rhodri were defeated in war and driven out, although there is no truth in the later tale that Llywelyn personally strangled Dafydd at Aberffraw. Instead both uncles died of natural causes.

Llywelyn also appreciated the need to gain powerful allies outside of Wales. To that end he corresponded with Philip Augustus, King of France, and negotiated to wed Princess Joan, King John's daughter. Since he already had a wife, Princess Rhunallt of Man, Llywelyn needed to persuade the pope to let him annul the marriage.

This was done by methods that recall the behaviour of Llywelyn's distant descendent, Henry VIII. Rhunallt had previously been married to his late uncle, Rhodri. After several years of back and forth, Llywelyn convinced the pope that Rhodri had consummated the marriage before Rhunallt was of age i.e. before the age of twelve. This was in spite of the testimony of witnesses, who stated that Rhodri himself declared he had not known his wife carnally.

The statement of the pope, dated 16 February 1205, was:

“It was also determined from the preceding that the girl herself was in her ninth year when the often said Rhodri married her by pledge, and in her tenth when she was conducted, and for a further two years was frequently in the one bed with him”.

Thus, despite a lack of evidence and Rhodri's own recorded statements, Llywelyn succeeded in having his uncle convicted of what we would call child abuse or pederasty. The scandal arose when Llywelyn needed to get rid of Rhunallt and re-marry an English princess. Needless to say, this was no coincidence.

His wife was duly set aside and – so far as I can see – vanished from the record. Rhunallt was so effectively written out of history that later generations of Welsh poets and writers didn't even know her name: in the sixteenth century certain 'bards' and their copyists stated that Llywelyn's first wife was Tangwystl ferch Llywarch Goch of Rhos, for which there is no early reference. Contemporary accounts and letters make it clear the unfortunate woman was Rhunallt, daughter of King Reginald of Man.

Published on December 09, 2021 03:37

December 7, 2021

Welshry of Gower

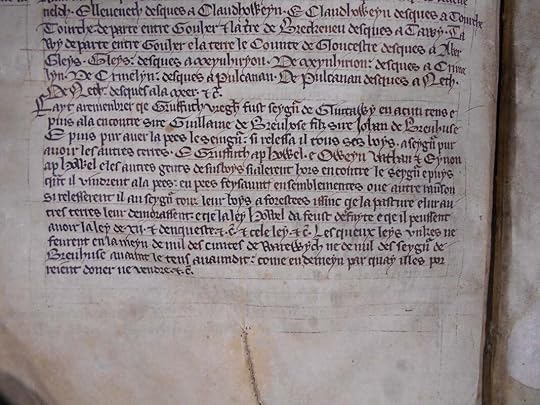

Another interesting fragment of medieval Wales. Attached is a document in Norman-French, which records that in 1287 Gruffudd Vregh, lord of Glyntawe, had rebelled against his lord William Braose, lord of Gower. In order to have peace, Gruffudd and his allies Gruffudd ap Hywel, Owain Fychan, Einion ap Hywel and other men gave up their afforested lands in order that they might keep their pasture and other lands. They also requested that the law of Hywel Dda be set aside and that they might have the law of twelve and inquest.

Another interesting fragment of medieval Wales. Attached is a document in Norman-French, which records that in 1287 Gruffudd Vregh, lord of Glyntawe, had rebelled against his lord William Braose, lord of Gower. In order to have peace, Gruffudd and his allies Gruffudd ap Hywel, Owain Fychan, Einion ap Hywel and other men gave up their afforested lands in order that they might keep their pasture and other lands. They also requested that the law of Hywel Dda be set aside and that they might have the law of twelve and inquest. Further context is provided in an English chronicle, the Breviate of Domesday. This records that in 1287 Rhys descended upon Gower with a large army and joined with the Welshmen of that country 'living in the upper part of the wood'. On the advice of Einion ap Hywel, Rhys attacked and burnt Swansea and took Oystermouth castle. After the revolt was over, it seems Einion and his comrades made a separate peace with Braose.

The most important individual among these Gower men was Gruffudd Vregh or Frech, which apparently means 'the spotted'. He is called lord of Glyntawe, but there was no such place in Gower. However a district of Breconshire, just over the border, was called Glyntawe in a record of 1493. This was a large parish, extending to the county of Carmarthen and, to the north, the Great Forest of Brecon, where Glyntawe Mill stood in 1651. On the southeast the parish reached the manor of Neath Ultra in Glamorgan.

In the sixteenth century many of the local families traced their ancestry back to a common ancestor, Gruffudd Gwyr, said to have acquired large possessions in Gower by marriage with an heiress of the 'ancient line of Dyfed'.

The immediate descendents of Gruffudd Gwyr were his son, our man Gruffudd Vregh, his nephew Gruffudd ap Hywel and grandson Einion ap Hywel. This, rather neatly, shows that the supporters of Rhys ap Maredudd in 1287 were a tight family unit.

After the settlement of 1287, Gruffudd Vregh and his kin were allowed to keep the land of Supraboscus of Llaniwg, the northern part of the parish now forming the manor of Caegurwen. The subsequent history is unknown, but in 1485 the manor was in the possession of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, a favourite of Henry VII. It was forfeited to the crown on the attainder of Sir Rhys's grandson in 1531, and passed into the hands of the Herberts.

Some explanation can be given for the request of English common law at the expense of Hywel Dda. Via the Statute of Wales of 1284, the Welsh besought Edward I that as far as lands and tenements were concerned, the truth of any dispute might be tried by jury i.e. common law. Welsh civil law would continue to be used with regard to contracts, debts, securities, covenants, trespasses and chattels. The reason was that tenants in Welshry had much trouble owing to sub-division of land among Welsh heirs, so it was not known where rent might be levied. Despite the request and grant of 1287, the custom of Hywel Dda persisted in this part of Gower as late as 1532.

Published on December 07, 2021 04:44

December 5, 2021

The other Wales

Hywel ap Meurig (died 1281) was one of the most important figures on the Welsh March in the late 13th century. It is impossible to understand events in Wales in this era without studying the careers of Hywel and men like him.

Hywel ap Meurig (died 1281) was one of the most important figures on the Welsh March in the late 13th century. It is impossible to understand events in Wales in this era without studying the careers of Hywel and men like him.He first appears as a royal negotiator for Henry III in 1260, and at about the same time entered the service of Roger Mortimer. In 1262 he was constable of the Mortimer castle at Cefnllys, where he and his family were captured by the supporters of Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd later that year. It seems they were freed when Mortimer appeared and negotiated a truce.

Hywel dips out of sight until 1271, as part of a group of Welsh supporters of John Giffard, fighting Prince Llywelyn in Cantref Selyf in northern Brycheiniog. In 1274 he was acting as a Mortimer agent, collecting information on Llywelyn's movements in Cedewain and Clun: one of his detailed spy reports to Lady Maud Mortimer survive. In the next year he appears as a royal surveyor of castles and lands in Carmarthen and Cardigan.

During his ten-year rule of the principality, Llywelyn experienced the utmost difficulty in controlling men such as Hywel. He resorted to hostage-taking and extracting bonds for good behaviour, which only made things worse. In 1276 he forced Hywel to surrender his son, Sion, as a guarantee of loyalty. Hywel was obliged to find sureties totalling £100, which was provided by other leading Welshmen of the Middle March.

This affair appears to have marked the point where loyalty to Llywelyn in the Marches crumbled away. In the war of 1276 Hywel was captain of an army of 2700 Welshmen drawn from the Middle March, which drove into Gwynedd and shattered Llywelyn's resistance. Among Hywel's captains were those men who had paid the surety for his son.

After the war Hywel was richly rewarded. He was put in charge of the construction of Builth castle and had a grant of the mine nearby; he was also appointed as one of two Welsh judges on the Hopton Commission, a royal enquiry into Welsh law and custom. Shortly before his death he was knighted, and his name and coat of arms appear in St George's Roll, a roll of arms associated with the Mortimer family. His family continued to prosper in royal service for decades.

The details of Hywel's career were hateful to the post-1800 generation of Welsh historians, who lauded Prince Llywelyn and the House of Aberffraw as national liberators from English tyranny. Sir James Conway-Davies, editor of the Welsh Assize Roll, refused to acknowledge that Hywel was even a Welshman: he simply dismissed him as an 'English knight'. Modern Welsh nationalists would probably regard Hywel as a Davy Gam figure: a contemptible quisling who allied with wicked imperialist foreigners instead of fighting for his nation.

Which is all nonsense. Hywel was a Welshman to his boots, a descendent of ancient Welsh kings, and a leading figure in the 'other Wales' i.e. that section of Welsh society that stands apart from the simplistic narrative of England vs Gwynedd.

Published on December 05, 2021 01:51

December 4, 2021

Delayed unions

On 12 January 1283, at Rhuddlan in Wales, Edward wrote to Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon. His letter concerned the long-delayed marriage between his eldest daughter, Eleanor, and Constance's son Alfonso.

On 12 January 1283, at Rhuddlan in Wales, Edward wrote to Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon. His letter concerned the long-delayed marriage between his eldest daughter, Eleanor, and Constance's son Alfonso. The policy behind the marriage probably lay in the desire of the Aragonese to find allies against Charles of Anjou's aggressive domination of Sicily. Constance was the daughter of Manfred, the last Hohenstaufen ruler of Sicily, killed in the Battle of Benevento in 1266. After the capture and beheading of her 16-year old nephew, Conradin, Constance inherited a claim to the Sicilian throne.

From Edward's perspective, he welcomed an opportunity to strengthen the defence of the Aragonese-Catalan border with Gascony. This is also suggested by his attempt to secure a second union, fulfilling a similar purpose, between his eldest son Henry and the heiress to the kingdom of Navarre.

When the Aragonese match was proposed, in 1273, bride and groom were underage. In recognition of their youth – and the dangers of childhood – their first names were not included in the treaty, in case one or the other died before reaching the age of canonical consent. If the worst befell, a sibling could be wheeled out as a substitute.

As Louise Wilkinson has recently argued, Edward's relationship with the women of his extended family is largely neglected. His six daughters who reached adulthood, for instance, tend to be treated as footnotes. This is a pity, since they were required to play active roles and very far from mere ciphers. As for Eleanor and Marguerite of Provence, his mother and aunt, they were as formidable as any male politician and exercised considerable influence over him. One of the current clichés is that Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II's consort, was an amazing strong woman and the strongest woman there ever was, was, was, because the wonderful Wizard of Oz. In fact she was just one of many (admittedly the sheer number of Eleanors can be confusing).

Their influence is shown in the surviving correspondence. In 1282 Edward was supposed to send his daughter, now thirteen and technically of age, to Aragon. Instead she remained in England and the marriage went unconsummated. This was, as he acknowledged in a letter to his advisers, due to the influence of his wife and mother. They had allied together to persuade Edward that his daughter was still too young, even though she was one year past the age of consent for women.

It may be the two Queen Eleanors reminded Edward of their own youthful marriages at the age of twelve and thirteen. The king might have been slightly embarrassed by such recollection: when he and Eleanor of Castile were first married, they had to be quickly separated because he got her almost immediately pregnant.

In the sample letter, Eleanor's departure was again delayed. This time Edward used the Welsh war as an excuse, and told Constance he needed to deal with the Palm Sunday revolt before he could return to the matter of the wedding. The bride's journey was then impeded again by Peter III's invasion of Sicily.

Even more delays followed. The pope sought to isolate King Peter by objecting to the Anglo-Aragonese union on the grounds of consanguinity: Eleanor and her husband shared a great-great-grandfather in Count Thomas I of Savoy. Edward's requests for papal dispensation fell on deaf ears, and the match was finally dissolved by Alfonso's death in 1291.

Published on December 04, 2021 03:55

December 2, 2021

Early Tudors (1)

Ednyfed Fychan, seneschal to Llywelyn the Great, died in 1246. He passed in the same year as Prince Dafydd, Llywelyn's younger son and heir, who had ruled North Wales for six years.

Ednyfed Fychan, seneschal to Llywelyn the Great, died in 1246. He passed in the same year as Prince Dafydd, Llywelyn's younger son and heir, who had ruled North Wales for six years. Dafydd was succeeded by two of his nephews, Owain Goch and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. For a time they shared power between them, which is reflected in their employment of Ednyfed's two sons, Gruffudd and Goronwy. Gruffudd was appointed as seneschal to Llywelyn, while his brother Goronwy served Owain in the same capacity.

So, there were two rulers and two seneschals in Gwynedd. This was an uneasy situation, reflecting Llywelyn the Great's difficult legacy. He had chosen to divorce his first wife in order to marry Joan, daughter of King John. This was part of a consistent Venedotian policy of intermarrying with the English royal family, to bolster their power in Wales and overawe rival dynasties.

According to a later tradition, Joan was resented by Ednyfed's family, later known as the Wyrion Eden. In the late 15th century John Tydir of St Asaph, an obscure poet of the Tudor lineage, composed a book of pedigrees that contains the following anecdote (rendered in modern English):

“Gruffudd ap Ednyfed Fychan fled to Ireland, for some slander given to him touching Joan, daughter of King John, wife of Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, and stayed there as long as the Prince lived, and was highly entertained”.

This is the Gruffudd appointed as one of the two co-seneschals in 1246. It is impossible to know where Tydir got his information from, but interesting that the Tudors maintained a tradition of defiance against Llywelyn the Great.

If the anecdote has a basis in reality, then this probably marks the first serious breach between the rulers of Gwynedd and the lineage they raised to power and privilege. This impression is supported by a grant of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd to Basingwerk abbey in 1247, in which Gruffudd ap Ednyfed Fychan appears as one of the witnesses.

Gruffudd's eminence lasted until 1256, when he headed a Welsh diplomatic mission to Henry III. After that, he is heard of no more.

Published on December 02, 2021 04:13

December 1, 2021

The Irish Sea (2)

In October 1294 Prince Madog ap Llywelyn and his followers crossed the Menai strait and sacked the new castle and borough of Caernarfon. They destroyed the official documents of the English colonists, housed in the exchequer, and killed or drove away the tax officers.

In October 1294 Prince Madog ap Llywelyn and his followers crossed the Menai strait and sacked the new castle and borough of Caernarfon. They destroyed the official documents of the English colonists, housed in the exchequer, and killed or drove away the tax officers. Only two months later, December, the castle of Kildare in Ireland was captured by a band of Irish and English. They were led by one Calvagh, or An Calbhach O Conchobhair Failghe (O'Conor Faly) to give him his full name. This man was a constant thorn in the side of the English of the Leinster midlands. After sacking the castle, his men destroyed the rolls of the administration:

“Calvagh combussit rotulos et tallius comitatus”.

Calvagh may have been in alliance with Maurice Mac Murrough, who was leading an anti-English revolt in Leinster at the same time. He appears to have copied the actions of Madog in Caernarfon, although there is no way of knowing if the rebels in Wales and Ireland were in contact. At the least, the dramatic events in Wales must have been widely reported on the other side of the Irish Sea.

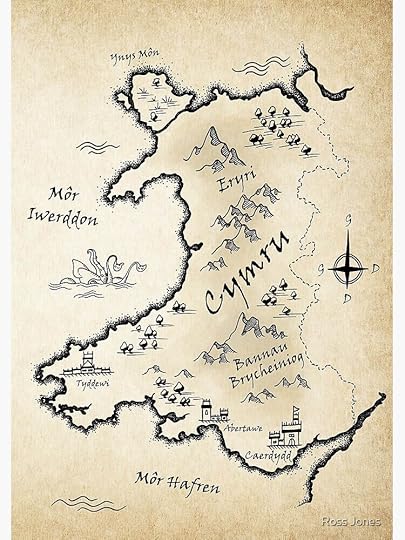

The Irish went on to raid Newcastle McKynegan in April 1295. This was a few weeks after Madog's disastrous defeat at Maes Moydog in mid-Wales, and possibly before news had reached Ireland of Welsh misfortunes. However, the Irish soon became aware that King Edward had crossed to Anglesey and begun work on another of his mighty castles. The Dublin annalist reported that:

“Edward, king of England, built the castle of Beaumaris in Venedotia, which is called the mother of Wales, and commonly Anglesey, entering it after Easter, and subjugating to his imperium the Venedotians, that is, the powerful men of Anglesey”.

The same annalist reported the capture of Madog in these terms:

“...and immediately afterwards, namely, around the feast of the Blessed Margaret, Madog, then the 'electus' of Wales, placing himself at the king's mercy, was led to London by Lord John Havering, and shut in the Tower, awaiting the king's mercy and will”.

The failure of Madog's revolt seems to have discouraged the Irish. On 19 July, shortly before the Welsh prince surrendered to Edward I, Maurice Mac Murrough and the Leinster rebels were formally received into the king's peace. They probably surrendered because the king had forced John Fitz Thomas – called 'Mac Geraillt' in Irish annals – to release the Earl of Ulster from captivity. His return to power stabilised English control of the lordship.

The English response was much less draconian than in 1282. Edward I and his advisers had realised that bloodshed was a short-term fix, and they could only retain control via compromise. There was no repeat of the butcher's work at Shrewsbury, where Prince Dafydd had been tortured to death in front of a baying crowd. Instead Prince Madog was confined for life in the Tower; his sons were taken into royal service and eventually permitted to have their inheritance.

Maurice Mac Murrough got off more lightly. When he and his kin met with the king's 'custos' or keeper of Ireland, they had to pay a ransom of 600 cows. They also had to agree to pay damages and hand over hostages for a term, but otherwise went free.

Published on December 01, 2021 05:27

November 30, 2021

The Irish Sea (1)

In late 1294 simultaneous revolts broke out in Wales and Ireland. The timing may have been more than coincidental, especially since this had happened before: in 1282, when the princes of Gwynedd rose against Edward I, the Mac Murrough of Leinster went into revolt at exactly the same time.

In late 1294 simultaneous revolts broke out in Wales and Ireland. The timing may have been more than coincidental, especially since this had happened before: in 1282, when the princes of Gwynedd rose against Edward I, the Mac Murrough of Leinster went into revolt at exactly the same time.Further, the rebellions of 1294 on both sides of the Irish Sea were led by members of the same dynasties. The leader of the revolt in North Wales was Prince Madog ap Llywelyn, kinsman to the late princes Llywelyn and Dafydd. In Leinster the ringleader was Maurice, son of Murtaugh, late co-leader of the Mac Murrough. Back in 1283, Murtaugh and his brother Art had been murdered by an agent in the service of the English government. Now Maurice took up the sword.

The revolts were triggered by circumstances. Edward I had stripped his garrisons in Wales for a campaign in Gascony, leaving them vulnerable. Meanwhile Ireland was in a state of confusion, thanks to a feud between the earl of Ulster and John fitz Thomas FitzGerald, baron of Offaly. When the earl was seized and imprisoned by his enemies in Kildare, the entire lordship of Ireland was destabilised.

Madog and Maurice took advantage of the sudden weakness of English power. Direct evidence is lacking, but they may have been in contact: Madog's revolt started on Anglesey, only a skip away from Ireland, and the inhabitants of the isle had many blood links to Irish families.

In April 1295 the Irish of the Wicklow mountains broke out and devastated Leinster, burning the strategic castle of Newcastle McKynegan and other vills. At the same time the Welsh revolt was in full swing in north, south and west.

One important aspect of these revolts, highlighted by Séan Duffy, is the action of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester and lord of Glamorgan. Clare went to Ireland in October 1293, taking his wife and a large army with him. English annals describe his expedition:

“Hearing that the magnates of Ireland had begun cruelly to lay waste and destroy the very abundant lands which he had in Ireland, crossed over to Ireland, taking his wife, the countess, and an innumerable abundance of warlike men, and thus entirely subdued his shameless and savage enemies, some of them being killed, others driven away”.

While it appears Clare defeated his enemies in Ireland, his absence from Wales allowed the Welsh on his Glamorgan estates to run riot under their leader, Morgan ap Maredudd. Thus the earl was faced with war on both sides of the Irish Sea, and the Welsh insurgents who rose against him in Michaelmas 1294 took advantage of the crisis he faced in Ireland.

Published on November 30, 2021 04:32

November 29, 2021

Wyrion Eden

“I venture to say that no war can be long carried on against the will of the people” - Edmund Burke

“I venture to say that no war can be long carried on against the will of the people” - Edmund BurkeThe above quote is taken from Fiona Watson's upcoming revised edition of Under the Hammer, a study of Edward I and Scotland. It struck me that the quote could just as well apply to medieval Wales.

The most important kin-group in Wales were the Wyrion Eden, descendents of Ednyfed Fychan, seneschal to Llywelyn the Great, and ancestors of Henry VII. This extended family rose to power thanks to the policy of Llywelyn the Great and his successors, who wanted to establish a proper ministerial elite in Wales. To that end the heirs of Ednyfed Fychan were promoted to rank and privilege, and exempted from customary services; for instance, they were granted townships for a very free tenure, with the sole obligation of attending the prince's court.

In the Welsh wars of Edward I virtually the entire lineage abandoned Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and defected to the king. The reasons for this shocking collapse in the prince's power base are still not entirely clear. In the aftermath of conquest they continued to hold the privileged status enjoyed under the princes. They were not totally compliant, however: several of the family joined the revolt of Prince Madog, only to reconcile with the king afterwards.

The behaviour of the family in the revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr, over a century later, was the complete opposite. With a couple of exceptions, the Wyrion Eden threw their weight behind the revolt, which partially explains why Henry IV experienced such difficulty in suppressing it.

Although the family made a 'patriotic' choice in supporting Glyn Dwr, the consequences were disastrous. Many were killed in the revolt, although those who survived were not generally persecuted. However, the glory and influence of the family, which had dominated Gwynedd for a century and a half, was departed.

The man who picked up the pieces was one Gwilym ap Gruffudd ap Gwilym, a descendant of Tudur Fychan, a member of the lineage who had supported Edward I. Gwilym was the heir to a rich patrimony in North Wales, and rose high in crown service: in the reign of Richard II he served as steward of the commote of Menai and sheriff of Anglesey, among other posts.

Gwilym's immediate family threw themselves into the Glyn Dwr revolt. His wife's uncles were heavily involved, and his own father and uncle were killed in the early stages. He and his brother did not join Glyn Dwr until 1402, and might have been pressured into it. They were among the first Welshmen to submit to Henry IV, in August 1405.

The revolt was far from spent at this stage, but Gwilym seems to have decided there could only be one outcome. He certainly profited from his early submission. Desperate for support among the Welsh, Henry re-appointed Gwilym to the 'rhaglawry' – bailiff – of Dindaethwy, a post he held for the rest of his life.

This was only the start. In March 1407 Prince Henry (later Henry V) granted Gwilym's forfeited lands, along with those of 27 other Welsh rebels, to Hugh Mortimer. Eight months later Gwilym persuaded the king to restore his estates, as well as everything else that had been granted to Mortimer. Then, in 1410, Gwilym acquired the lands once owned by his kinsman, another Gwilym. Thus he may be said to have pieced together the shattered Tudor inheritance.

This smart, ruthless operator also profited from the marriage market. After the death of his first wife, Morfudd, he married in 1405 Joan Stanley, daughter of Sir William Stanley of Hooton in Cheshire. To ensure the succession of his children by Joan, he disinherited his son by Morfudd, Tudur Fychan.

His son by Joan, Gwilym junior, inherited his father's vast estate and sharp political antennae. Along with the heirs of other survivors of the Glyn Dwr revolt, Gwilym adopted an Anglicised form of his name. This was not a craven surrender to English domination: rather, he appears on deeds as either Gwilym or William, dependent on context.

Gwilym/William was even more ambitious than his father. He established himself at Penhryn, where the vast estate and manor house were henceforth associated with the family. They continued to rise in wealth and influence: his son became chamberlain of North Wales and in 1489 his grandson was knighted by Henry VII.

Published on November 29, 2021 04:54

November 28, 2021

The soul of the lady Eleanor

Eleanor of Castile, queen of England, died on this day in 1290. She breathed her last at Harby in Nottinghamshire, in the house of a local knight, Sir Richard Weston.

Eleanor of Castile, queen of England, died on this day in 1290. She breathed her last at Harby in Nottinghamshire, in the house of a local knight, Sir Richard Weston.Richard had supported the baronial reformers during the crisis of Henry III's reign, and in November 1266 was one of nine Montfortian knights accused of impeding the royalist sheriff, John Balliol, from performing his duties in Notts and Derbyshire. Richard had held the office of coroner in Nottinghamshire, and was ordered to appear before the Exchequer in 1267, to account for his misuse of revenues. It appears he had been transferring the money to the king's opponents rather than the royal appointee as sheriff.

He returned to the king's allegiance in October 1266, when he was one of many rebels who received letters of protection after submitting at Kenilworth. Afterwards Richard continued to serve as county coroner, and in 1268 finally took up the duties of knighthood. This was only because in that year all Lincolnshire landowners with land to an annual value of £20 were distrained to become knights.

Richard's wife, Agnes, brought him the estate in Harby in which Queen Eleanor died. His father-in-law, Brian de Herdeby, was a reasonably well-off local landholder. He appears a few times in local land deeds, and in 1272 came to an agreement with the master of the Knights Templar concerning a road over land he had conceded to the order. Brian's conventional existence as a local officer and justice was interrupted by the civil war, in which he also sided with the rebels. His land was briefly confiscated in 1265, following the battle of Evesham, for being in the service of the rebel baron, Gilbert de Gant.

There was a strong Montfortian element in these close-knit county families. Richard arranged for the marriage of his eldest son, Hugh, to the daughter of Richard Foliot. Foliot was yet another old Montfortian, accused of sheltering baronial rebels on his estates in northern Notts and southern Yorkshire. With exceptional timing, he had changed sides just before Evesham, which meant he was well-placed to grab a share of forfeit rebel land in the aftermath.

Although a man of some standing, Richard Weston's fortunes gradually declined. His son Hugh died in 1288, which removed the possibility of inheriting part of the Foliot estate. An attempt to place one of his younger sons, a cleric named William, to the rectory of Weston, met with failure. Richard also fell into debt, possibly a long-term consequence of having to buy back his lands in 1266. Despite being forced to take up knighthood, he seems to have avoided doing any military service in these years, perhaps because it was so expensive.

Shortly before the dying queen arrived at Harby, Richard was obliged to sell off his manor of Weston to one Henry de Pierrepoint, at a knock-down value of 50 silver marks. This far less than the actual worth of the land, and implies Richard had grown desperate; he was possibly also in debt to Henry, and sold the land cheap as a way of discharging part of his obligation. This explains why Richard was living at Harby instead of Weston when the royal household passed through the area.

Eleanor was accompanied by her husband, King Edward. Preoccupied with his wife's illness and the crisis in Scotland, the king had no qualms about accepting the hospitality of a former rebel. By this stage the Montfortian wars were ancient history, and it is doubtful Edward had any memory of Richard Weston. Fortunately the royal household was well equipped to provide for its own needs, so the presence of so many people in Harby didn't add to Richard's financial woes.

From Richard's perspective, Queen Eleanor's last illness was a Godsend. While the royal couple were in his house, he persuaded Edward to do him some favours. On 23 November a charter of free warren was made out to Richard Weston, 'the king's host'; this granted Richard and his wife exclusive hunting rights over the beasts of the warren over their lands. Anyone else who hunted there without permission would be liable to a penalty of £10. This was fee payable to the crown, while the damages went to Richard.

That was not all. On 29 November, the day after Eleanor died, the king issued a writ to the sheriff, ordering him to cease persecuting Richard Weston and his family for outstanding debts. On 29 or 30 the king and his court left Harby with Eleanor's body, never to return.

Richard was not forgotten, however. With his usual clumsy handling of affairs, he got himself in a scandal at Nottingham, where he served as a justice of gaol delivery. In November 1291 he and a fellow justice, William of Colwick, were accused of tampering with the records of the court. Seventy jurors swore to their guilt, which meant Richard was in serious trouble. Before he could be put on trial, however, he was pardoned on the verbal command of the king.

This was conveyed to the court by the chief justice, Gilbert Thornton, 'for the love of the Virgin Mary and the soul of the Lady Eleanor, former queen of England and his consort'. The matter had been discussed in parliament, held at the archbishop of York's manor in London, where the king ordered that Richard Weston should be remitted from any fine 'because the lady queen his consort had died at Richard's house in Harby'. William of Colwick, on the other hand, had to pay a fine of £10.

The advantages Richard gained from the royal visit were only temporary. His fortunes continued to decline, and by 1300 he and his wife were engaged in a fire-sale of their remaining lands. In July the elderly knight was desperate enough to strap on his armour, for the first time in over thirty years, and do military service in Scotland: he served as a mounted constable in charge of 577 Nottinghamshire archers at the siege of Caerlaverock in Galloway.

Meanwhile his wife, Agnes, continued to sell off land. Perhaps worn out by the Scottish campaign, Richard died in January 1301. He was probably in his 60s. His widow embarked upon a legal dispute against the Pierrepoints, who had bought the manor of Weston, as well as the Knights Templar and other neighbouring landholders. Against the odds, Agnes managed to claw back enough land to provide for her widowhood. This lasted for at least 18 years, but she drops out of sight after 1319.

Published on November 28, 2021 02:45

November 27, 2021

Cornering the market

In January 1278 a commission was appointed on Anglesey to provide remedies for injuries done to the king's men on the isle after the conclusion of the Treaty of Aberconwy.

In January 1278 a commission was appointed on Anglesey to provide remedies for injuries done to the king's men on the isle after the conclusion of the Treaty of Aberconwy.Among these was one Iorwerth Foel. He complained that, when he had made peace with the king and served in his army, Prince Llywelyn had seized his horses and corn and the plunder taken by his men, and had later burned his houses. As a result he dared not cultivate or inhabit his hereditary lands or enter the principality.

The surviving tax and subsidy accounts show that Iorwerth was one of the richest men on Anglesey. Most taxpayers on the isle owned from one to six oxen, with two exceptions; Iorwerth, who had twenty, and Einion ap Iocyn, who had sixteen. At this stage oxen were still considered more economical for ploughing work, although the horse was increasingly coming into use. Oxen and horses could also be used together in the plough-team.

At the royal court or maerdref of Aberffraw, an ancient royal court on the isle, there were 265 head of cattle. The largest herds were again those of Iorwerth and Einion, at sixteen and fifty head respectively. They had not cornered the market in sheep, however: the largest flock was that of Adda ap Einion, who had fifty.

The 69 recorded taxpayers on Anglesey owned a total of 1184 bushels of oats, 468 of wheat and 204 of barley, along with 80 mixed barley and peas. The largest quantity of wheat, 80 bushels, was owned by that man Iorwerth, while he and Einion each had 160 bushels of ground oats.

In terms of animals and crops – the things that mattered in a subsistence economy – Iorwerth was in the top bracket of landholders on Anglesey. This enabled him to kit himself out as a 'centenar' or mounted officer of infantry; in 1298 he was one of four centenars of Anglesey who led infantry to northern England to recover Berwick and Roxburgh from the Scots under William Wallace. Why Prince Llywelyn could not retain the loyalty of such a man is a moot point: we could argue the toss until the oxen came home, but what we really need is a Tardis and a tape recorder.

What can be said is that Iorwerth and his family shifted smoothly from one regime to another. As a reward for his support of the king, he was granted lands in Aberffraw along with the farm of the ringildry of the cantref at a reduced rate. He was the richest taxpayer there, listed on the subsidy roll for 1292-3. His son Gruffydd was one of the most prosperous burgesses of Newborough in 1352.

Published on November 27, 2021 05:06