David Pilling's Blog, page 15

November 1, 2021

This obnoxious crusader

In November 1271 a Frankish army of about 7000 men left Acre and marched south, towards Jerusalem. It consisted of King Hugh Lusignan and the barons of Cyprus, Lord Edward and a force of English and Scottish knights, some Turkish mercenaries, and a company of Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic knights.

In November 1271 a Frankish army of about 7000 men left Acre and marched south, towards Jerusalem. It consisted of King Hugh Lusignan and the barons of Cyprus, Lord Edward and a force of English and Scottish knights, some Turkish mercenaries, and a company of Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic knights.Even in November, the Franks struggled with the heat. They marched by night and rested by day, until the fortified town of Qaqun came in sight. This was their target.

Qaqun had a long history. Prior to the Crusades, an Arab village existed on the site. In 1110 it was held by a Frank, Eustace Garnier, as part of his lordship of Caesarea. The population consisted of Syrian Christians, Frankish settlers and possibly some Muslims. The lord governed through an Arabic-speaking interpreter called a dragoman.

Over time the Hospitallers acquired part of Qaqun, as did the Benedictine Abbey of St Mary Latin in Jerusalem. In 1187 the Master of the Temple, Gerard of Ridefort, summoned men from the Templar 'convent' at Qaqun to fight a Muslim force near Galilee. French sources relate that the Templars were destroyed in a battle near Nazareth the following day, although a few survivors returned to Qaqun.

The Frankish lordship came to an end in 1265, when the town fell to Sultan Baybars along with Caesaera and Arsuf. The next year he restored the castle and converted the church into a mosque. Baybars intended to make Qaqun not only his principal military base in the Sharon plain, but also the centre of a new administration replacing the old Frankish district.

For as long as the Franks remained in the Holy Land, the Mamluk base at Qaqun threatened their very survival. It also posed a direct threat to Pilgrim Castle, a Frankish stronghold to the north, and guarded the approach to Jerusalem. Unless Qaqun was recaptured, there could be no advance on the Holy City.

Baybars himself had gone north, to repel a Mongol invasion of Syria. The Golden Horde came at the behest of Lord Edward, who had sent envoys to the il-khan as soon as he landed at Acre. Unknown to Baybars, the English prince was using the Mongols as bait. While the Mamluk field army marched off into Syria, the crusaders struck at Qaqun.

The attack started on 23 November. Islamic writers give the most detailed accounts. Before assaulting the town itself, the Franks ambushed a large encampment of Turks or Turcomans. These were accompanied by a large herd of horses and cattle and led by two local emirs, as well as the governor of Qaqun. This would suggest the encampment was a supply column, heading for the castle.

Relying on darkness, the Franks charged into the camp shortly before dawn. They slew one of the emirs, badly wounded the second, slaughtered a thousand Turcopoles and took five thousand head of cattle. After destroying the column, the Franks charged on to assault Qaqun. This was guarded by a strong tower, surrounded by ditches full of water. The governor, who had escaped the ambush, apparently ran away.

Word of the attack reached Baybars at Aleppo on 4 December. He had been bushwhacked; a new experience for the sultan, who generally beat up the Franks without much difficulty. He quickly returned to Damascus and organised a relief operation. This was led by the emir Jamal al-Din Aqush al-Shamsi with troops raised from Ain Jalut.

At the sight of the relief force, King Hugh and Lord Edward decided to withdraw. They were advised to retreat to the Military Orders, who had become very risk-averse: perhaps because they had so few knights, and couldn't afford any more disasters.

As they withdrew the Franks were chased and overtaken by the Mamluks, who ordered them to return certain prisoners. They refused, and a rearguard action ensued which left a number of men killed and horses and mules hamstrung. According to a Muslim report, the latter numbered 500 head; not a good day to be a horse.

The Chronicle of Melrose, composed in Scotland, supplies another anecdote. During the retreat, a Scottish squire turned aside to answer a call of nature. Midway through his business, he was jumped by a band of Mamluks and carried off into slavery. Never to be seen again, poor lad.

The rest of the Franks reached the safety of Pilgrim Castle, driving prisoners and cattle before them. Afterwards they returned to Acre. Of the failed attack on Qaqun, Baybars sarcastically remarked:

“If so many men cannot take a house, they are unlikely to conquer the Kingdom of Jerusalem.”

Even so, the whole affair had given Baybars a nasty shock. The Mongol alliance in particular was a cause for concern: the sultan's chief fear was ending up surrounded by an alliance of Franks-Mongols-Armenians. He fixed his sights on Edward, 'this obnoxious crusader', as Islamic chroniclers called him.

Qaqun remained a sizeable Arab village until the 1940s, when it was destroyed by Israeli forces during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Today only the medieval tower-keep and some derelict structures are still standing. The tower is choked with rubble and cactus, although the graves of the mosque and a cistern can still be seen.

Published on November 01, 2021 08:44

The battle of Monstrelet

In early 1413 the Duke of Clarence set about recovering a host of towns and castles in the vicinity of Bordeaux, previously captured by the French. He was able to do this due to previous treaties with the Duke of Orléans and the Counts of Armagnac and Albret. Via these agreements, Clarence's French allies agreed to recognise Henry IV as rightful Duke of Guyenne. In exchange the English king promised not to support the Duke of Burgundy against Orléans.

In early 1413 the Duke of Clarence set about recovering a host of towns and castles in the vicinity of Bordeaux, previously captured by the French. He was able to do this due to previous treaties with the Duke of Orléans and the Counts of Armagnac and Albret. Via these agreements, Clarence's French allies agreed to recognise Henry IV as rightful Duke of Guyenne. In exchange the English king promised not to support the Duke of Burgundy against Orléans.Clarence quickly rolled back all the French conquests of the previous nine years. French agents hurried back to Paris to report that the English had encountered little resistance in Guyenne; they were persuading the duchy's inhabitants to recognise Henry's lordship 'as if they were securely ensconced in London surrounded by their compatriots'. When the spring came round, unless a large French army was dispatched at once to Guyenne, the English would not be stopped.

The Estates-General in Paris met on 30 January 1413. Here a barrage of abuse was directed at the incompetence and corruption of the government; the Count of Armagnac, it was said, had persuaded many other French lords to join Clarence. Unless something was done, these French traitors would 'destroy the kingdom'.

Under pressure, the government ordered the French marshal in Guyenne, Jacques de Heilly, to take action. We should feel pity for Jacques, one of history's fall guys. He had repeatedly warned the council in Paris that he was short of money and men, and could achieve little without reinforcements. Regardless, he was ordered to take action. Then, in April and May, Paris was engulfed by the 'Cabochien' uprising and the French court resumed its suicidal power struggle.

Jacques was left out on a limb. Despite his misgivings, he tried to do his duty and marched for the town of Soubise, in northern Guyenne, which was besieged by the English under Thomas Beaufort, earl of Dorset. When he heard of the French approach, Beaufort lifted the siege and turned about to confront the marshal in open battle at Monstrelet.

The result was the most complete English victory since the days of the Black Prince. News of Beaufort's triumph was sent back to England, though it arrived too late for Henry IV. He died in March 1413, and the battle was fought in August. The news was accompanied by a string of French prisoners: Jacques de Heilly himself, along with the seigneur de Morlet, the bastard of Clynton, the lord en le Sale de Mary, the Mayor of La Rochelle, the captain of Rions, and many others.

Beaufort's victory was celebrated in London, but the reception elsewhere in England was somewhat muted. By this stage many of the English regarded Guyenne, a distant province in southwest France, as not worth the candle. John Hardyng, however, was upbeat about the 'great honour' achieved by Clarence and his men, while the Polychronicon admitted that Clarence had set Guyenne 'at peace and rest'.

Otherwise the battle of Monstrelet is completely obscure. If one was a nasty, cynical sort of person, one might suspect the influence of Henry V in this. One of his first acts as king was to award Beaufort's esquire, sent to Westminster with news of the victory, a fee of £20. Yet the success of Clarence's expedition was a humiliation for the new king. Henry had been completely opposed to the pro-Armagnac policy of his brother and late father, and stayed at home while Clarence went off and saved Guyenne. His faulty judgement had been exposed, not a great start.

There is no evidence that Henry deliberately suppressed the memory of Monstrelet. Yet Beaufort's victory is completely crushed under the shadow of Agincourt, fought just two years later. When Henry returned from the Agincourt campaign, he was greeted in London with a carefully organised victory parade, reminiscent of the return of conquering generals in ancient Rome. As the head of an unstable usurper regime, Henry needed to ensure that all the military glory went to himself. Clarence could get back in line, and stay there.

Published on November 01, 2021 06:09

October 31, 2021

The rescue of Guyenne (2)

"And I pronounce you the favoured one, and fortunate in war. As a result of which great fortune was bestowed on Thomas, a most noble prince and knight".

"And I pronounce you the favoured one, and fortunate in war. As a result of which great fortune was bestowed on Thomas, a most noble prince and knight".Thus the chronicler John Strecche describes Henry IV appointing his second son, Thomas of Clarence, to the command of an army in 1412. Clarence and his captains, the Duke of York and the Earl of Dorset, were dispatched with 4000 men to rescue the duchy of Guyenne.

Thanks to bad weather, the English fleet of fourteen ships was unable to sail from Southampton until 1 August. The expeditionary force had been thrown together with impressive speed, but not quick enough. France was already on a war footing, and in June a French army marched south from Paris to Bourg, a ducal stronghold in northern Guyenne.

The French were led by the king, Charles VI, and the duke of Burgundy. They arrived to find Bourg defended by Henry IV's ally, the duke of Berry, and a force of Armagnacs. So, a French army laid siege to a Gascon town defended by some other Frenchmen on behalf of the English.

After a month of heat, thirst and dysentery, the two sides came to terms. Berry, who was in his 70s and had moved house seven times to avoid French cannonballs, agreed to a treaty. In return for renouncing the English alliance, he and the other Armagnac lords – or 'Judases', as Charles called them – were taken back into the fold.

If the news reached Clarence before he set off, it made no difference to his plans. The English adopted an interesting strategy. On previous occasions, when Guyenne was threatened by the French, the usual thing was to send troops and supplies direct to the duchy. In 1412 Clarence did something new and sailed for Normandy. His army disembarked on 10 August at Saint-Vaast-le-Houge on the Cotentin peninsula. Perhaps this was symbolic: sixty-six years earlier, Edward III had landed here for the campaign that climaxed at the battle of Crécy.

Clarence marched inland to find a substantial French force waiting in the Cotentin to repel him. He smashed it aside and advanced through Normandy towards the Loire. Shortly afterwards, 22 August, the French held a council of war at Auxerre inside the church of Saint-Germain. This was presided over by the Dauphin, Louis, since his father King Charles was suffering one of his bouts of insanity.

The French agreed that the English must be removed from France; the question was how. Clarence had been reinforced by six hundred Gascons, and his army was now burning and looting its way through Anjou. At this point French unity started to fragment again. Several of the Armagnac lords who had recently submitted to King Charles now drifted back to the English camp. Among them were big hitters such as the Count of Alencon, the Duke of Orléans, and the lords of Armagnac and Albret.

In mid-September the English reached Blois. Here they were met by heralds sent by the duke of Berry. Since their letters were addressed to King Henry and the Prince of Wales, Clarence declined to receive them. In his response, the duke expressed disbelief that Berry would betray the English – which he had already done – and his confidence that the Frenchman would 'mind his faith and loyalty'. Perhaps this was a bluff, or even a joke.

One thing was for certain: Clarence was not for shifting unless someone paid him a bribe. When the lords of France complained they had no money, the citizens of Paris retorted that it was up to those who had invited the English in to make them go away. Meanwhile the English continued to wreak utter havoc, as per the standard tactics of the day: burning, looting, kidnapping, destroying towns and churches, etcetera.

This went on for two months. Finally, in mid-October, the Armagnac lords bowed to pressure and opened talks with Clarence. These resulted in a treaty of 14 November, whereby the English received a huge payment of £40,000 in exchange for leaving France by 1 January 1413. Pledges were given in the form of money and hostages, and King Charles – now lucid again – pledged to grant the English safe-conduct to Bordeaux.

Once this was all confirmed, Clarence set off for Guyenne. The monkish chronicle of Saint-Denis remarked that, once the English had got what they wanted, they ceased burning and killing and 'behaved on their march more moderately than the French'. This presumably means that French troops were using the war as cover to ravage parts of France.

Clarence arrived at Bordeaux on 11 December. His expedition has been misunderstood by many, then and now. Chris Given-Wilson, in his superb biography of Henry IV, explains the context:

“The choice facing the English government in 1411-12 was the prioritization of Calais or Guyenne. The upshot, Clarence's expedition, shocked and shamed the French. This was the first major English campaign in France for a quarter of a century, and the sight of Clarence's army marching virtually unchallenged from Normandy to Bordeaux, being handed a Danegeld of £40,000, and then settling in to enforce its claim to Guyenne, revived the reputation of English arms abroad and struck terror into the French”.

Published on October 31, 2021 05:29

October 30, 2021

The rescue of Guyenne (1)

In 1412 Henry IV publicly declared his intention to sail to Gascony – called Guyenne in this period – to recover his duchy from the French:

In 1412 Henry IV publicly declared his intention to sail to Gascony – called Guyenne in this period – to recover his duchy from the French:“To cross the sea, God willing, to the parts of Guyenne, there to recover and retain our heritage of our duchy of Guyenne from the hands of our enemies, adversaries and rebels who for a long time have held it against us.”

To his English subjects, this must have been a very familiar tune. The Plantagenet kings had been singing it ever since 1259, when Guyenne was converted into a fiefdom, held of the French crown. When the French took advantage of Henry's domestic problems to invade the duchy in 1403, it was merely the latest in a string of invasions. Every time, by one means or another, the French had been thrown back. This was due to the stubborn courage and loyalty of the Gascons, and the willingness of the Plantagenets to pump massive resources from England into the defence of Guyenne.

Between 1403-1412, it must have looked as though the game was up. Distracted by civil war in England, a serious revolt in Wales, as well as conflicts with Scotland, Flanders and Brittany, Henry could send no aid to Guyenne. The Gascons were left isolated, and had to repel the might of France all by themselves. The resistance of the chief city of Bordeaux in particular can only be described as heroic, although few remember it. Certainly not in France, where the awkward history of English Guyenne is firmly stuffed under the carpet:

“This proud episode in Bordeaux's history has often been disregarded, especially by earlier more chauvinistic French historians, who could not comprehend the strong particularism of the Gascons and could not believe that the fifteenth-century men of Guyenne regarded the French as even more foreign than the English.” - Margaret Labarge

Outside of Bordeaux, the outnumbered Gascons and a few English auxiliaries were obliged to fight guerilla warfare against the overwhelming armies of France. Castles and towns changed hands with bewildering frequency; it didn't help that Bayonne, in the south, was briefly taken over by an anti-Lancastrian faction.

By 1411, despite his own appalling health and a chronic lack of money, Henry had somehow managed to climb out of a very deep hole. On 11 June he announced a five-year truce with Flanders, and on 1 January 1412 a ten-year truce with Brittany. A six-year truce with Scotland was also agreed. These agreements, plus the improved situation in England and Wales, released him to concentrate on Guyenne.

The situation in the duchy was desperate. Bordeaux was surrounded, and the Archbishop reduced to sending pitiful letters to the king. One of his letters, dated June 1406, is typical:

“I have written to you so many times and so lengthily concerning the state of your land, and I have cried so much that my voice has become hoarse.”

Bordeaux was granted a reprieve when a French assault on Bourg, to the north, failed due to bad weather and a tremendous battle fought between the contending fleets in the Gironde river. Under heavy fog, the Anglo-Gascons launched fire ships against the French fleet, which was largely destroyed; afterwards one of the flaming vessels was sent upstream to taunt the French commander, the Duke of Orléans. The Saint Albans chronicler remarked that the ship 'burnt in the eyes of the proud duke'.

In 1411-12 all of England's available resources were directed to the relief of Guyenne. Henry's health had improved somewhat, but he was not strong enough to lead the expedition. Nor would he entrust it to his eldest son, the later Henry V, because father and son disagreed over strategy. Put simply, Henry senior favoured an alliance with the Armagnac faction in France, while Henry junior favoured their bitter rivals, the Burgundians.

Instead the king gave command to his second son Thomas, duke of Clarence. Henry promised the men of Guyenne that he would send a force of 1000 men-at-arms and 3000 archers. He was as good as his word. Half were recruited by Clarence, and the other half by his fellow commanders, the duke of York and Thomas Beaufort, former and future lieutenants of Guyenne. By 9 July at least £16,00 had been raised for the expedition, a remarkable sum after a decade of ceaseless warfare. It had to scraped together: Archbishop Arundel donated a loan of 1000 marks, while the king threw in 200 marks from his own personal fund or 'chamber money'.

Published on October 30, 2021 06:08

An unwanted parcel

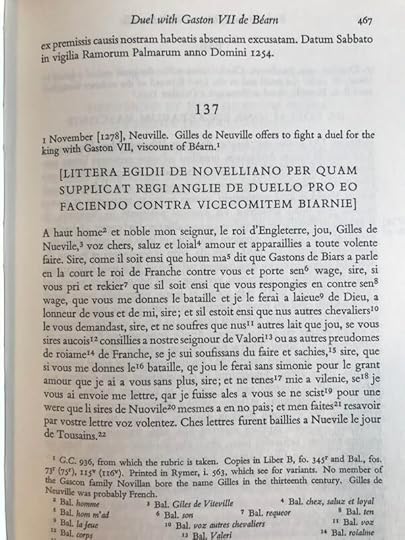

Attached is a letter dated 1 November 1278, in which one Gilles de Neuville offers to fight a judicial duel in place of Edward I. The man he offered to fight on the king's behalf was Gaston de Béarn, the troublesome viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony.

Attached is a letter dated 1 November 1278, in which one Gilles de Neuville offers to fight a judicial duel in place of Edward I. The man he offered to fight on the king's behalf was Gaston de Béarn, the troublesome viscount of Béarn in southern Gascony.The letter is an interesting example of the rules of 'courtoisie' in the late 13th century courts of Paris and Westminster. At this point in time the ruling dynasties on both sides of the English Channel spoke the same language and observed the same laws and customs.

This was not chivalry, however. The contemporary term for correct behaviour was 'débonaireté; we still associate the term 'debonair' with good manners, and this is where it came from. To be 'debonair' was to conduct oneself via the accepted tenets of politeness and courtesy.

Gaston had broken with custom. After his revolt in Béarn was crushed by Edward I in 1274, he had appealed to Paris. Once again this shows the awkward status of the Plantagenets on the continent after 1259. Edward could not do justice on his own vassal, even when the man was in armed revolt. Instead he had to submit to the judgement of his overlord, Philip III, king of France.

At the hearing in Paris, Gaston lost his temper, accused Edward of being a liar and threw down his gage. This was met with uproar: whatever their grievances, vassals did not challenge their lords to single combat. It was neither polite or courteous, and certainly not debonair.

Interestingly, it was a French knight who took exception. Gilles de Neuville was a knight of the French court, and not a member of Edward's household. Even so, he decided to stand up for the king of England and offer to beat the crap out of the insolent Gascon: this, Gilles declared, was for the sake of God and honour and the great love – grant amour – he had for Edward.

In this strictly mannered world, Gaston was probably considered an outsider. The northern French looked down on the people of Gascony. Their dialect, the 'langue d'oc', was considered uncouth and barbarous compared to the 'langue d'oi' spoken in the north. One 12th century French writer, a Poitevin priest, described the Gascons as:

“Verbose, cynical, lecherous, drunkards, and badly clothed”.

It also didn't help that Gaston was notorious. Everyone in Paris must have been aware of his past: he had first rebelled against Henry III in 1242, and afterwards revolted against the king's unpopular seneschal, Simon de Montfort.

The French king, Philip, was placed in a difficult position. From Rhuddlan in Wales, Edward wrote to his cousin, demanding the issue of Gaston be resolved in a manner appropriate to the honour of kings (honour de roiaute). Much as Edward might have appreciated Gilles's offer, he could not afford to let the combat go ahead. That would mean he had submitted to Philip's judgement, thus enforcing his subordinate status to the French crown. In his letters, Edward explicitly made the point that it was never his intention to make Philip the arbiter of the dispute.

In the end Philip deal with the problem by throwing it back at Edward. Gaston was packed off to England, under French escort, and appeared at Westminster with a halter round his neck. This was a fairly broad hint, but Edward stayed his hand. Shortly before Gaston's arrival, the king had received a message from his spy in Paris. This informed him of Philip's true intentions:

“I learn that Gaston de Béarn has been sent to you in England, accompanied by Monsieur Erart de Valeri and Monsieur Foulques de Laon, advisors of the king of France. Those who are thirsty for your honour fear that the aforementioned advisors do not work to mitigate the wrongs of the Viscount against you. I intend to say to your friends that peace to intervene will not be advantageous for you if Gaston, who sinned publicly, does not repent himself in the same way, if he does not repudiate in a full court the charges that he formulated there on your account.”

Edward chose to act on the spy's advice. Gaston was made to appear before parliament and retract all the charges he had made in Paris. This, the king declared, was equivalent to a full renunciation, so the process in law was now finished. It only remained to decide what punishment should be inflicted.

Tit-for-tat, Edward was 'pleased' to grant to Philip the responsibility of a penal sentence. Gaston was then sent back to Paris, like an unwanted parcel.

Published on October 30, 2021 04:42

October 27, 2021

The Gascon affair (3)

On Monday 27 November 1273 a document was sealed in the cloister of the priory of Mont de Marsan in Gascony. Marsan, the 'town of three rivers', lies on the border of the Landes forest, midway between the Bay of Gascony and the Pyrenees.

On Monday 27 November 1273 a document was sealed in the cloister of the priory of Mont de Marsan in Gascony. Marsan, the 'town of three rivers', lies on the border of the Landes forest, midway between the Bay of Gascony and the Pyrenees.The document was sealed in the presence and at the command of lady Constance, daughter of Gaston de Béarn. It was also witnessed by three clergymen, including the prior, and two squires. The preamble reads as:

“We promise, bind ourselves and swear as before that we will neither permit the entry of the said lord Gaston or any of his supporters into the said borough and town nor permit them to cause any hurt to the said lord king, his men-at-arms or his supporters, nor shall we offer him any kind of aid or cooperation for the duration of this war.”

The context was the revolt of Constance's father against Edward I in the winter of 1273. After gaining permission to take military action from the 'grand cour' of Gascony on 1 November, Edward marched into the Landes and forced the surrender of Marsan, the chief town. It was left to Constance to negotiate terms; her father had apparently fled south, to his mountain strongholds, leaving her to take the rap.

While the king was busy at Marsan, Gaston and his followers ran riot in the south. The rebels mounted at least thirty destructive mounted raids or chevauchées, of which some details survive:

“Item, chevauchées took place: one at Salas, another at Rupem Fortem de Cheursano, and animals were seized to the value of 20 pounds. Item, another at Seula, and another at Salas; and the church plundered. Item, another at . . . and damage done to wine, hay, oats, cloth, and other things, to the value of 30 pounds....”

Etc. After securing Marsan, Edward went south to prise the rebels from their castles in the mountains. This was no easy task. An English chronicler, Thomas Wykes, describes the royal army struggling to cope with Gaston's guerilla tactics. The rebels were:

“frequently coming and going and attacking the king's army in sudden assaults, more frequently inflicted not immoderate losses, and returning pompously with the booty they had captured, they protected themselves by the defence of the fortifications.”

Wykes, usually an admirer of Edward I, disapproved of the new king's decision to spend so much time in Gascony, instead of rushing home for his coronation. He claimed that Edward wasted money on the expedition, and described his soldiers 'wasting away by starvation and hunger'.

The chronicler's attitude may reflect a more general change. After the loss of their lands on the continent, the English nobility became more insular, and often had to be forced to do military service overseas. This was because they no longer had a stake in foreign wars, which offered little except the king's wages. Wars inside the British Isles, with confiscated land and loot on offer, were a different matter. For instance, in 1297 only six of the English gentry obeyed Edward's summons for military service in Flanders. On the Falkirk campaign, just twelve months later, over 2000 turned up.

The Plantagenets had a very different attitude. They were not just kings but 'grand seigneurs' of France, dukes of Aquitaine and counts of Ponthieu and Montreuil. Edward's decision to go to Gascony to save his ducal crown, instead of England, shows where the priorities of his dynasty lay.

Gaston prolonged his resistance into the new year. Edward had to summon the host of Gascony to crush the revolt, which came with its own difficulties. On 14 December 1273, for instance, the king was obliged to grant a charter to the men of the commune of Mimizan. In exchange for a small fee of 200 livres tournois, these men and their heirs were exempted from doing military service forever. Edward had more success at Bordeaux, where the mayor and citizens granted him the sum of 2000 livres for the war effort.

Finally, the rebels were cornered at Chateau Moncade near Gaston's town of Orthez. On 14 January 1274, via the mediation of a French cardinal, Gaston agreed to surrender unconditionally. His lands and castles were then confiscated by the king until a date was fixed for a trial at Westminster.

The surrender was deceptive. As soon as Edward turned north again, Gaston appealed over his head to the French parlement in Paris.

Published on October 27, 2021 06:01

October 25, 2021

The Gascon affair (2)

After his arrest in early October 1273, Gaston de Béarn was released from custody on condition that he stuck to his commitments. These were to provide compensation to the victims of the riot in Sault-de-Navailles, and to appear in the ducal court at Saint-Sever to answer further charges.

After his arrest in early October 1273, Gaston de Béarn was released from custody on condition that he stuck to his commitments. These were to provide compensation to the victims of the riot in Sault-de-Navailles, and to appear in the ducal court at Saint-Sever to answer further charges. As soon as he was free, Gaston returned to his stronghold of Chateau Moncade, near Orthez on the edge of the Pyrenees. Several weeks passed, in which he gave no sign of honouring his commitments. At the end of October Edward I summoned the four courts of Gascony – Saint-Sever, Bordeaux, Basaz and Dax – to give judgement on the suspected rebel.

This four-court system was a local variant on the English parliament of representatives. Edward was careful to abide by the custom due to his awkward status as a vassal of the King of France. If he gave the Gascons any cause for offence, they would appeal over his head to Paris. That might well end in sanctions against the English, or even confiscation of the duchy.

The assembly or 'grand cour' ordered the existing charges to be read out against Gaston. These included his repeated refusals to answer a royal summons: the seneschal of Gascony, Luke de Tany, reported that he had six times dispatched envoys to Gaston to appear before the king, and six times his men were violently repelled. The assembly then asked itself the question – what judgement should be executed, based on law and custom?

While all this chat was in progress, Gaston made plans. He had quietly recruited the support of over 90 members of the Gascon gentry, a significant percentage of the nobility of the South. Their names and titles are listed in the surviving accounts: only a handful were major lords, and some were illegitimate sons of the gentry. Even so, altogether they held over thirty castles, strung out along the foothills of the mountains.

The court at St-Sever appears to have been completely unaware of what was going on. At the end of October it ruled that, since Gaston had already refused several summons, he would be given one more chance to comply. If he failed, the king was authorised to use military force.

Shortly before or after the final summons, Gaston triggered his revolt. His followers rode out from their strongholds to plunder villages and towns all over southern Gascony. Most significantly, they seized the fortified town of La Réole.

La Réole, overlooking the river Gironde, was a tough nut to crack. During the last two major revolts in Gascony, in 1224 and 1253, the rebels had made it their headquarters. The place held out stubbornly against Henry III and Simon de Montfort in 1253-4, and only surrendered after the marriage deal with Alfonso of Castile cut the rebels off from any hope of external support.

Now the troublesome town had been occupied a third time. As the southern half of Gascony went up in flames, the 'grand cour' was forced to a hasty decision. On 1 November King Edward was granted permission to summon the feudal host of Gascony and march against the rebels – 'convoqua l'ost et marcha en armes contre lui'.

Published on October 25, 2021 07:31

October 24, 2021

The Gascon affair

In late September 1273, in a 'grande cour' or great court at St-Sever in southwest Gascony, Edward I received the homage of the local gentry. This was after he had performed homage for the duchy to Philip III in Paris. At this point, therefore, the King of France stood at the apex of the feudal pyramid, with the King of England on the step below, and the lords of Gascony on the third tier below him.

In late September 1273, in a 'grande cour' or great court at St-Sever in southwest Gascony, Edward I received the homage of the local gentry. This was after he had performed homage for the duchy to Philip III in Paris. At this point, therefore, the King of France stood at the apex of the feudal pyramid, with the King of England on the step below, and the lords of Gascony on the third tier below him.While at St-Sever, Edward also tried to deal with the revolt of Gaston Moncada, viscount of Béarn on the northern edge of the Pyrenees. Gaston had been quiet for twenty years, ever since Henry III negotiated a marriage for his heir, Edward, to Eleanor of Castile. In theory, the marriage neutralised the threat of any further Castilian invasions of Gascony. It also cut out the likes of Gaston and his fellow peers of the South, many of whom had strong blood-ties with the kingdoms of Spain beyond the mountains.

The last time the Castilians had attacked Gascony, in 1253, Gaston had deserted Henry III and thrown in his lot with the invaders. He was lured away by the promise of being made seneschal of Gascony, once the English were driven out. It didn't happen, and Henry rather generously allowed Gaston's head to remain on its shoulders. The eighth Henry, he of the marriage and waistline issues, may have taken a different view.

For some reason – no historian, English or French, has ever figured out why, exactly – Gaston went into revolt again in 1273. Possibly he hoped to exploit Edward's absence on crusade and conquer the province of Bigorre. There were several claimants to this much-desired bit of real estate, including the Montfort clan.

At the start of his reign, Edward preferred to negotiate with his enemies rather than crushing them. Perhaps his later attitude was influenced by the general failure of this policy. He sent one of his knights, Gérard de Laur, to open talks with Gaston and try and persuade him to stop being silly. As soon as the English envoy arrived at Sault-de-Navailles, a town on the very edge of the mountains, Gaston's men stirred up a riot. Géraud was arrested by the citizens and thrown into prison.

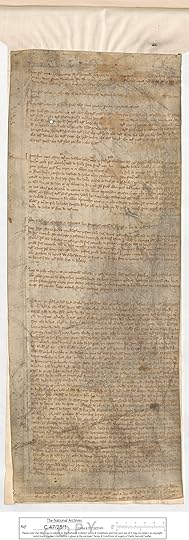

The rioters then attacked English loyalists in the town. A detailed report on what followed was later sent to the king. It survives to this day, held in the National Archives. The report, written in a difficult Gascon dialect, states that 'many bad things were done to the King's people in Sault'. A list of bad things follows:

Item: Two men were seized, beaten, and robbed of ten shillings

Item: The miller of Sault was arrested and robbed of a horse

Item: Four pack-horses belonging to a local marquis, loaded with fish and other foodstuffs, were stolen

Item: A 'certain man' of Bayonne was robbed of his fish

Item: Two packhorses belonging to a certain gentleman were stolen, along with 150 shillings

Item: Two other gentlemen were arrested and robbed of 6 pounds 2 shillings

Item: A ship was plundered of 80 'conches' – a Gascon unit of measurement, not a seashell – of millet stolen

And so on. All of this was done, the report states, at Gaston's consent and command. While the riot was in progress, he was at 'Mons Marciani' or Mont de Marsan in central Gascony, where he fixed his headquarters. It is difficult to see what Gaston hoped to achieve. Perhaps he was simply prodding the new king, to see what he could get away with.

A swift military or police action followed. Within days Gaston was arrested and imprisoned at Sault, the location of the riot. On 2 October, while in prison, he promised to abide by whatever judgement the court at Saint-Sever chose to inflict on him. This was to be a rapid process: as part of the vow, Gaston promised to pay compensation to his victims by 6 October.

(Thanks to Dr Shelagh Sneddon for translating the 1273 report)

Published on October 24, 2021 04:40

October 23, 2021

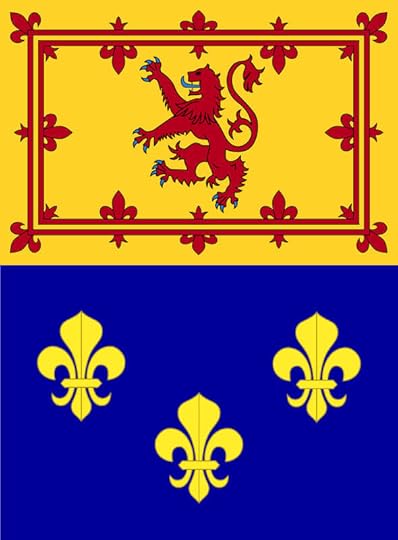

The Auld Alliance, sort of

On this day in 1295 – or yesterday, according to the online text – the precursor to the 'Auld Alliance' was sealed in Paris. One interpretation is that the treaty was one of mutual aid, intended to deter further English aggression towards both kingdoms.

On this day in 1295 – or yesterday, according to the online text – the precursor to the 'Auld Alliance' was sealed in Paris. One interpretation is that the treaty was one of mutual aid, intended to deter further English aggression towards both kingdoms.The English were certainly the aggressors in Scotland, where Edward I had manipulated the Scottish succession crisis from start to finish. In France, however, it was the precise opposite. Philip the Fair provoked a war in Gascony by deliberately breaking his word to Edward's brother, Edmund of Lancaster. His policy was every bit as devious and dishonest, with malice aforethought, as Edward's policy in Scotland. One Edwardian scholar, Maurice Powicke, remarked that the policy of the two kings in these respects was almost like a 'sick parody' of the other.

Very few French historians have attempted to defend Philip's conduct. J Trabut-Cussac, editor of the Gascon register, remarked that he found it impossible to doubt the sincerity of the English desire for peace in Gascony. Charles-Victor Langlois concluded that Philip was guilty of outrageous duplicity. A rare dissenting voice was Edgard Boutaric, writing in 1870, who declared that Philip took 'appropriately energetic' measures against the perfidious English; a view borne of 19th century nationalism, perhaps.

The treaty itself is not a straightforward pact between France and Scotland. It is a treaty of alliance between France and Norway, in which Scotland is included as a third party. The Norwegian envoys made impossible guarantees: in exchange for 50,000 livres tournois for every year of the war, they promised that Erik II would provide the French with 200 helms, 100 warships and 50,000 soldiers.

It seems strange that Philip and his canny advisers would credit such promises. Yet it seems they did, since the Norwegians left Paris with a down-payment of 6000 marks. Predictably, when push came to shove, Norway coughed up not a sausage to help the French war effort.

There is a very nasty sub-plot. The Norwegian envoy who negotiated the above deal was one Audun Hugleiksson. He was later suspected of setting up the 'False Margaret', an impersonator of the Maid of Norway, and using her in a plot against King Erik's successor, Haakon V. Haakon was not a man to be trifled with: he had the woman burnt at the stake, beheaded her husband, and hanged Audun at Nordnes in Bergen.

Published on October 23, 2021 04:09

October 22, 2021

Prince Roger of Wales?

On 9 October 1281 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and his cousin Roger Mortimer sealed a treaty at the Mortimer castle of Radnor. The two men agreed to a perpetual peace and swore to support each with all their power in time of war and peace.

On 9 October 1281 Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and his cousin Roger Mortimer sealed a treaty at the Mortimer castle of Radnor. The two men agreed to a perpetual peace and swore to support each with all their power in time of war and peace. Two exemptions were preserved. Llywelyn swore to support Mortimer against everyone save the king; 'saving fidelity in all things as is freely owed to the lord king of England'. Mortimer agreed to hold against all Llywelyn's enemies except the king and his younger brother, Lord Edmund. The treaty was witnessed by the bishops of Hereford and St Asaph.

Unfortunately the reasons for the treaty are not explained, which provokes speculation. One theory is that Llywelyn wished to make Mortimer his heir. This was not so unlikely: Mortimer was the senior surviving male descendant of Llywelyn the Great and Joan Plantagenet.

Inheritance via the female line was technically forbidden under Welsh law. However, Llywelyn was perfectly willing to break with custom for political ends. Among other things, he abandoned customary food renders in Wales in exchange for cash, introduced alien weights and measures, and enabled the use of dower – also forbidden under Welsh law – within his principality.

A ruler prepared to do all that was not going to shy away from meddling with lines of descent. Especially if it meant securing the future of Wales: at this point, in 1281, Llywelyn's only heir was his brother Dafydd, who had spent the past decade trying to kill him. The prince himself was in his 60s, old for the time, and had fathered no male heirs. Mortimer, on the other hand, had a thriving family of at least four sons and three daughters.

There are other hints. Mortimer's cousin, Roger of West Wales, named his eldest son Llywelyn. The boy was born between 1265-95, and is the only example of a Mortimer being given a Welsh patronymic in this era. Otherwise the family stuck to Norman/English names, principally Roger and Edmund.

Further, Mortimer was very active in Welsh Wales – Pura Wallia - at this time. In 1277 he was appointed by the king to oversee the partition of land in North Wales between Prince Dafydd and Owain Goch; two years later he was put in charge of the administration of the Perfeddwlad, and made keeper of Llanbadarn Fawr and the whole land of West Wales. These appointments effectively made him a greater power in Wales than Llywelyn, whose authority had been virtually destroyed via the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1277.

At the same time as the Radnor agreement, Llywelyn also quit his rights in the land of Gwrtherynion to Mortimer. The Mortimers had been fighting for centuries to secure this land, in mid-Wales, and now the Prince of Wales yielded it to them.

The overall implication of the treaty is that Llywelyn wanted something from Mortimer, but Mortimer gave nothing obvious in return. He was under no obligation to make pacts with his old enemy, so why do it?

One might interpret the Radnor agreement as a canny move by Llywelyn. Mortimer had the blood of Welsh princes in his veins, was politically astute, and riding high in favour at the English court. He was particularly close to Edward I, and it is difficult to imagine him suffering the same fate as the luckless Dafydd.

Whatever the motive, the treaty was soon blown to the winds. In March 1282, just a few months later, Llywelyn joined – or was dragged into – the Palm Sunday revolt triggered by his brother, Dafydd. A few months after that, in November, Mortimer died of natural causes, probably dysentery. A few weeks after that, Llywelyn was murdered by Mortimer's sons, Edmund and Roger junior.

Published on October 22, 2021 03:42