The rescue of Guyenne (2)

"And I pronounce you the favoured one, and fortunate in war. As a result of which great fortune was bestowed on Thomas, a most noble prince and knight".

"And I pronounce you the favoured one, and fortunate in war. As a result of which great fortune was bestowed on Thomas, a most noble prince and knight".Thus the chronicler John Strecche describes Henry IV appointing his second son, Thomas of Clarence, to the command of an army in 1412. Clarence and his captains, the Duke of York and the Earl of Dorset, were dispatched with 4000 men to rescue the duchy of Guyenne.

Thanks to bad weather, the English fleet of fourteen ships was unable to sail from Southampton until 1 August. The expeditionary force had been thrown together with impressive speed, but not quick enough. France was already on a war footing, and in June a French army marched south from Paris to Bourg, a ducal stronghold in northern Guyenne.

The French were led by the king, Charles VI, and the duke of Burgundy. They arrived to find Bourg defended by Henry IV's ally, the duke of Berry, and a force of Armagnacs. So, a French army laid siege to a Gascon town defended by some other Frenchmen on behalf of the English.

After a month of heat, thirst and dysentery, the two sides came to terms. Berry, who was in his 70s and had moved house seven times to avoid French cannonballs, agreed to a treaty. In return for renouncing the English alliance, he and the other Armagnac lords – or 'Judases', as Charles called them – were taken back into the fold.

If the news reached Clarence before he set off, it made no difference to his plans. The English adopted an interesting strategy. On previous occasions, when Guyenne was threatened by the French, the usual thing was to send troops and supplies direct to the duchy. In 1412 Clarence did something new and sailed for Normandy. His army disembarked on 10 August at Saint-Vaast-le-Houge on the Cotentin peninsula. Perhaps this was symbolic: sixty-six years earlier, Edward III had landed here for the campaign that climaxed at the battle of Crécy.

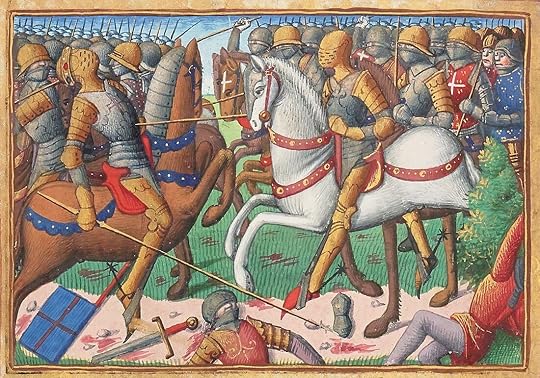

Clarence marched inland to find a substantial French force waiting in the Cotentin to repel him. He smashed it aside and advanced through Normandy towards the Loire. Shortly afterwards, 22 August, the French held a council of war at Auxerre inside the church of Saint-Germain. This was presided over by the Dauphin, Louis, since his father King Charles was suffering one of his bouts of insanity.

The French agreed that the English must be removed from France; the question was how. Clarence had been reinforced by six hundred Gascons, and his army was now burning and looting its way through Anjou. At this point French unity started to fragment again. Several of the Armagnac lords who had recently submitted to King Charles now drifted back to the English camp. Among them were big hitters such as the Count of Alencon, the Duke of Orléans, and the lords of Armagnac and Albret.

In mid-September the English reached Blois. Here they were met by heralds sent by the duke of Berry. Since their letters were addressed to King Henry and the Prince of Wales, Clarence declined to receive them. In his response, the duke expressed disbelief that Berry would betray the English – which he had already done – and his confidence that the Frenchman would 'mind his faith and loyalty'. Perhaps this was a bluff, or even a joke.

One thing was for certain: Clarence was not for shifting unless someone paid him a bribe. When the lords of France complained they had no money, the citizens of Paris retorted that it was up to those who had invited the English in to make them go away. Meanwhile the English continued to wreak utter havoc, as per the standard tactics of the day: burning, looting, kidnapping, destroying towns and churches, etcetera.

This went on for two months. Finally, in mid-October, the Armagnac lords bowed to pressure and opened talks with Clarence. These resulted in a treaty of 14 November, whereby the English received a huge payment of £40,000 in exchange for leaving France by 1 January 1413. Pledges were given in the form of money and hostages, and King Charles – now lucid again – pledged to grant the English safe-conduct to Bordeaux.

Once this was all confirmed, Clarence set off for Guyenne. The monkish chronicle of Saint-Denis remarked that, once the English had got what they wanted, they ceased burning and killing and 'behaved on their march more moderately than the French'. This presumably means that French troops were using the war as cover to ravage parts of France.

Clarence arrived at Bordeaux on 11 December. His expedition has been misunderstood by many, then and now. Chris Given-Wilson, in his superb biography of Henry IV, explains the context:

“The choice facing the English government in 1411-12 was the prioritization of Calais or Guyenne. The upshot, Clarence's expedition, shocked and shamed the French. This was the first major English campaign in France for a quarter of a century, and the sight of Clarence's army marching virtually unchallenged from Normandy to Bordeaux, being handed a Danegeld of £40,000, and then settling in to enforce its claim to Guyenne, revived the reputation of English arms abroad and struck terror into the French”.

Published on October 31, 2021 05:29

No comments have been added yet.