The Gascon affair

In late September 1273, in a 'grande cour' or great court at St-Sever in southwest Gascony, Edward I received the homage of the local gentry. This was after he had performed homage for the duchy to Philip III in Paris. At this point, therefore, the King of France stood at the apex of the feudal pyramid, with the King of England on the step below, and the lords of Gascony on the third tier below him.

In late September 1273, in a 'grande cour' or great court at St-Sever in southwest Gascony, Edward I received the homage of the local gentry. This was after he had performed homage for the duchy to Philip III in Paris. At this point, therefore, the King of France stood at the apex of the feudal pyramid, with the King of England on the step below, and the lords of Gascony on the third tier below him.While at St-Sever, Edward also tried to deal with the revolt of Gaston Moncada, viscount of Béarn on the northern edge of the Pyrenees. Gaston had been quiet for twenty years, ever since Henry III negotiated a marriage for his heir, Edward, to Eleanor of Castile. In theory, the marriage neutralised the threat of any further Castilian invasions of Gascony. It also cut out the likes of Gaston and his fellow peers of the South, many of whom had strong blood-ties with the kingdoms of Spain beyond the mountains.

The last time the Castilians had attacked Gascony, in 1253, Gaston had deserted Henry III and thrown in his lot with the invaders. He was lured away by the promise of being made seneschal of Gascony, once the English were driven out. It didn't happen, and Henry rather generously allowed Gaston's head to remain on its shoulders. The eighth Henry, he of the marriage and waistline issues, may have taken a different view.

For some reason – no historian, English or French, has ever figured out why, exactly – Gaston went into revolt again in 1273. Possibly he hoped to exploit Edward's absence on crusade and conquer the province of Bigorre. There were several claimants to this much-desired bit of real estate, including the Montfort clan.

At the start of his reign, Edward preferred to negotiate with his enemies rather than crushing them. Perhaps his later attitude was influenced by the general failure of this policy. He sent one of his knights, Gérard de Laur, to open talks with Gaston and try and persuade him to stop being silly. As soon as the English envoy arrived at Sault-de-Navailles, a town on the very edge of the mountains, Gaston's men stirred up a riot. Géraud was arrested by the citizens and thrown into prison.

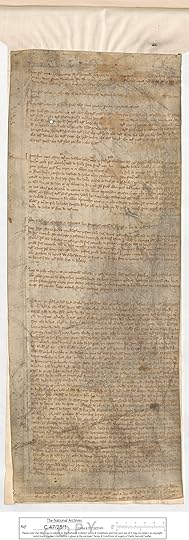

The rioters then attacked English loyalists in the town. A detailed report on what followed was later sent to the king. It survives to this day, held in the National Archives. The report, written in a difficult Gascon dialect, states that 'many bad things were done to the King's people in Sault'. A list of bad things follows:

Item: Two men were seized, beaten, and robbed of ten shillings

Item: The miller of Sault was arrested and robbed of a horse

Item: Four pack-horses belonging to a local marquis, loaded with fish and other foodstuffs, were stolen

Item: A 'certain man' of Bayonne was robbed of his fish

Item: Two packhorses belonging to a certain gentleman were stolen, along with 150 shillings

Item: Two other gentlemen were arrested and robbed of 6 pounds 2 shillings

Item: A ship was plundered of 80 'conches' – a Gascon unit of measurement, not a seashell – of millet stolen

And so on. All of this was done, the report states, at Gaston's consent and command. While the riot was in progress, he was at 'Mons Marciani' or Mont de Marsan in central Gascony, where he fixed his headquarters. It is difficult to see what Gaston hoped to achieve. Perhaps he was simply prodding the new king, to see what he could get away with.

A swift military or police action followed. Within days Gaston was arrested and imprisoned at Sault, the location of the riot. On 2 October, while in prison, he promised to abide by whatever judgement the court at Saint-Sever chose to inflict on him. This was to be a rapid process: as part of the vow, Gaston promised to pay compensation to his victims by 6 October.

(Thanks to Dr Shelagh Sneddon for translating the 1273 report)

Published on October 24, 2021 04:40

No comments have been added yet.